Chinua Achebe’s early literary production included four novels in eight years. The first three, Things Fall Apart (1958), No Longer at Ease (1960), and Arrow of God (1964), together referred to as “the African Trilogy,” are constructed around precolonial and colonial Igbo society and postcolonial Nigeria. His fourth novel, A Man of the People (1966), went beyond the Umuofia-verse and is set in an unnamed African country in the early 60s, a period marked by Independence movements across the continent.

In that novel, party politics is the game and no longer would the quality of a man’s thought be gauged by what he says. The book famously “predicted” a military coup, the writer letting his imagination ponder the severity of tensions in the country since Independence in 1960. It’s now part of literary history, how his great contemporary J.P. Clark, having read an advance copy, burst into a room filled with Nigerian writers, and shouted, “Chinua, I know you are a prophet. Everything in this book has happened except a military coup!”

A coup, led by Major Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu, would unravel only days afterwards. It was January 1966. A counter coup, which ousted Major General Aguiyi-Ironsi, followed in July. The tribal and political implications of these coups culminated in a war, the Nigerian forces against the secessionist Biafra, occupying the Eastern part of the country. Achebe, born in Ogidi to Igbo parents, fled the unsafe Lagos and took on an ambassadorial role for Biafra.

He stopped work on a novel he was writing, committing to more urgent forms like nonfiction and poetry. He won a Commonwealth Poetry Prize for the collection Beware, Soul Brother (1971), but it was his essays that helped broaden an era of new Africanist thinking, which sprung up as resistance to the politicking that threatened to undermine everything freedom was supposed to mean.

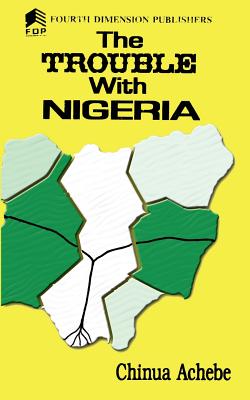

The deeply enlightening pamphlet The Trouble with Nigeria (1983), unarguably his most incisive thinking on the Nigerian condition, assumes an intensely critical voice—most times towards the country’s leaders—and in every listed Trouble such as “Tribalism” and “False Image of Ourselves,” the sharpness of his thought clarifies the obscure, making factual and psychological observations at every turn.

In the former piece, he notes the “strange thing that thing happened at our independence in 1960”:

Our national anthem, our very hymn of deliverance from British colonial bondage, was written for us by a British woman who unfortunately had not been properly briefed on the current awkwardness of the word tribe.

His argument was that, across the country, the unity and supposed brotherhood of its diverse peoples and philosophies was a farce. Less than six years after Independence, he wrote, “we were standing or sprawling on a soil soaked in fratricidal blood.”

Achebe’s political relevance arises from the doggedness of Nigerian oppression. By engaging his work less as instructive material and more as a chronicle of oppression, one sees Achebe as a modern voice, one who still has so much to say eight years after his demise.

Achebe’s close friend, the poet Christopher Okigbo, was among the millions of Biafrans who lost their lives during the war. His cousin, a soldier in the North, was also killed. The oppression and psychological trauma visited upon Biafrans, as well as the novelty of their three-year tussle with Nigeria, gives the war great narrative verve. As such, books, films, and anecdotes will always survive of that affair.

The disappearance of the character Kainene in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s opus Half of a Yellow Sun makes for great fan discussion across mediums of popular culture. Her missing tugs at the nature of the human mind to round off things, to see them finish. Adichie has often responded that the war took many people like Kainene, promising youth who left home and didn’t return.

What that book’s popularity—and indeed many of the material on the War—proves is that what is lacking in complementing, and perhaps articulating, our empathy is factual and current information.

One May Day in 2016, at least 100 people were massacred by the Nigerian military across the Southeast and South-south regions. It was Biafra Remembrance Day, a yearly event to honor the slain victims of the War. The stories of what went down across all five Igbo states, as well as in Asaba and Port Harcourt, are chilling: bullets, blood, the military razing through bodies, despair thick like smoke hanging over the streets of hot zones like Onitsha and Aba.

Across the southeast, there are more resident soldiers than in any other non-violent part of the country. Always on standby, the word “Biafra” becomes their invitation to kill and torture. Amnesty International investigated, and interviewed people who saw the carnage first hand and were survivors themselves. Bodies of slain demonstrators are said to have been loaded onto trucks and scattered in nondescript locations around the states, an unmistakable gesture to inspire fear and ire.

With the media failing to report these incidents with the urgency they demand, it isn’t surprising that they become stale merely days after. Meanwhile, with each closed mouth, the gun tears through the southeast and, in the devastating way of monsters, becomes more powerful. Though it sprawls the country, it is obvious that we do not realize how truly close the gun is.

Last year, the End SARS protests dragged the menace of military exuberance to the mainstream. The youth-led demonstration went on for weeks, garnering international attention. Given Nigeria’s population, it became a hot topic in a social media-driven world.

On 20 October 2020—a date now etched into Nigerian history—at the Lekki Toll Gate, many of us watched a live stream from the entertainer DJ Switch’s Instagram, and we heard the gunshots and saw one felled protester, the Nigerian flag draped over his bloodied body. As queries about that night persisted, CNN released an investigation on the shooting, with strong visual evidence that DJ Switch had been right—as opposed to the lies of the Lagos State governor—and that soldiers had been at the venue, firing live rounds into the crowd of protesters. That they were responsible for the death of over 15 people, with many more injured.

And yet before the Lekki Massacre, LGBTQ protesters agitating for their unique issues—profiling, abuse, all legal-backed—were sidelined by most heterosexual protesters who felt they would “derail” the mission to end police brutality.

Amara, an openly queer woman, shared a video where she spoke of fellow protesters snatching her placards and sending her away. She was visibly pained; hours later, the tweet was trending and the Nigerian LGBTQ community engaged in heated conversations with people who just couldn’t see how related things were.

A lady brought a 🌈 rainbow flag

— AmaraOlisa (@the_amarion) October 14, 2020

and our fellow

protesters turned on us at Berger Roundabout Abuja.

they tore our placards and seized the flag.

I got it back but they refused that we fly it.

I wore it on my neck and they refused.

said we either take it off or leave.

I’m leaving pic.twitter.com/ZyaTzR7TQg

Both the military’s extrajudicial killings and the public’s homophobia show how oppression functions, on levels, in Nigeria. Unless we address oppression on a holistic level, we are bound to remain stuck.

A similar problem plagues the Shiites, a minority Muslim organization whose members have been killed in their hundreds in the north of Nigeria, in Zaria and Abuja, infamously. Since 2015, they have protested the imprisonment of their leader Ibrahim Zakzaky, who’d actually been cleared for release by a court. Two years ago, presidential spokesman Garba Shehu went on TV to defend the Federal Government’s naming of the Shia-led Islamic Movement of Nigeria (IMN) as a terrorist organization, consequently justifying the untold horrors meted out to them.

Like Goodluck Jonathan’s Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act of 2014, these declarations act against the human right to life and association, but they succeed because Nigerians are pitted against themselves by politicians with scores to settle. A sinister tone accompanies news about all three—pro-Biafra groups, LGBTQ people, Shia Muslims—and if you read between the lines, you would see the threats and you-can-do-nothing-about-its.

Once in a while, a writer such as Chinua Achebe comes along to trace the genealogy of oppression in their country. Where contemporary thinkers are given to easy solutions, his work traces the origin of the problem.

It might seem disingenuous to point fingers at the British, but, in truth, they don’t deserve omission. Achebe argued that the colonial regime was “the most extreme form of totalitarianism.” Decades later, Nigerian leaders are still collaborating with these old establishments to loot the nation empty, and they do this by trying to stifle the freedom—mental and otherwise—of its people.

It says a lot that, in the Nigerian popular consciousness, Chinua Achebe remains known as “the author of Things Fall Apart.” Not only do his essay collections not make the curricula in most Nigerian universities, their intrinsically important themes have been conveniently blunted as “old school,” even though they are more relevant than anything anyone else has said about Nigeria in decades.

Recently, none other than the former governor of Lagos State Bola Tinubu is being mentioned as a potential choice for the Nigerian presidency in 2023. In one tweet, he was hailed as “an African Philosopher” with “incomparable political sagacity and strategic compilations,” a description whose verbosity told of its deceit. An overwhelming majority of reactions rejected the ridiculous idea of elevating a politician who has been accused of corruption and godfatherism to the helm of national politics.

Similarly, the UK’s The Guardian caught flack for publishing a distasteful piece by the novelist Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani, wherein she praises Yemi Osibanjo for “[defying] expectations as Nigeria’s vice-president.” It is incredibly offensive that many people—intellectuals and writers, among them—are working to whitewash the images of people who, by the offices they hold and have held, are deeply complicit in the problems of Nigeria today.

I spoke to a journalist friend at a media workshop we both attended not too long ago. Until recently, he’d been a reporter at a Southeast-focused outlet. He understood deeply the ripple effects of oppression across the region and what it means for Nigeria. I asked him if he wasn’t scared of telling such truths, considering the powerful people he’d upset if he continued to do so. His reply was both illuminating and refreshing, particularly coming from a young writer living in the country. He said, “Most Nigerian writers are not as idealistic as they should be.” The state of Nigeria leaves little to the imagination, so that slowly we’re stripped of our morality, that child-like dedication to building the perfect world.

Achebe, while alive, rejected a number of national honors, choosing to stay nonpartisan after a brief stint with politics. In The Trouble with Nigeria, he defines Patriotism as “an emotion of love directed by a critical intelligence.” In another chapter, he expresses a similar sentiment. “I [believe] that, hopeless as she may seem today, Nigeria is not absolutely beyond redemption,” he writes. “To pull her back and turn her around is clearly beyond the contrivance of mediocre leadership. It calls for greatness.”

Achebe’s words are urgent: he seems to look on from the other side, holding everyone to integrity. 2023 is only two years away, and the same old politicians have begun their dance. We can cheer or we can observe closely, calling for accountability like his writings empower us to. It’s crucial to our destiny that we choose wisely. Achebe has done his part.

2 Responses

This is a beautifully-written informative piece.

Wow!

Just wow