When she was six years old, Shugri Said Salh was sent to live with her grandmother in the desert of Somalia. Born in 1974, she spent her early years there as a nomad. She learned to navigate the harshness—drought, predators, and enemy clans—but also to appreciate the beauty, innovation, traditions, and powerful feeling of unity passed down in the Sufi community.

The outbreak of the Somali Civil War saw the displacement of millions of people. Salh fled to a refugee camp on the Kenyan border. In 1992, she migrated to North America. She went on to attend nursing school at Pacific Union College, California.

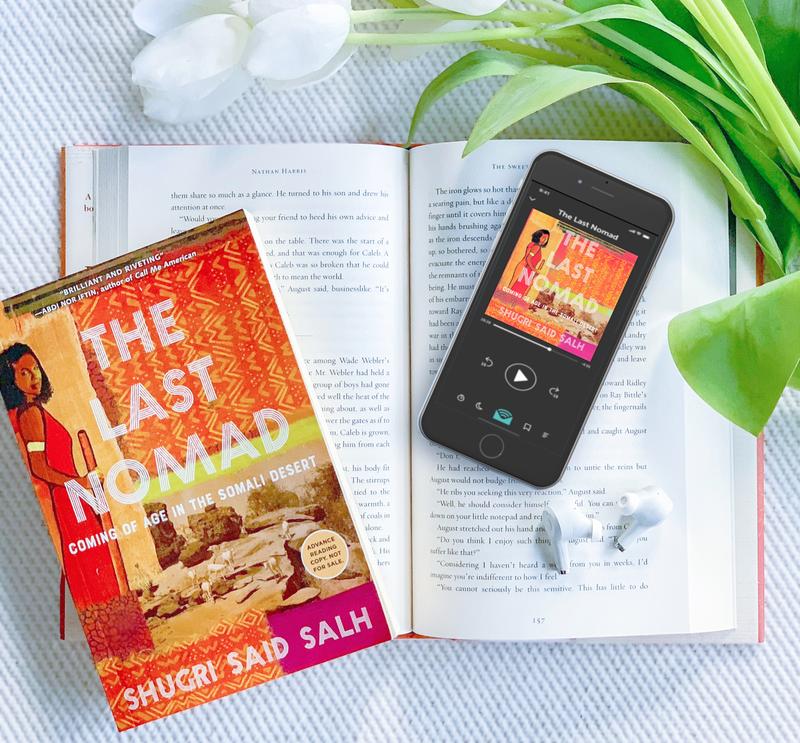

This year, Salh, who lives with her husband and children in Sonoma County, California, released a new memoir, The Last Nomad: Coming of Age in the Somali Desert, published by Workman Publishing. In it, she narrates her growing up, survival, and adjustments to new ways of life. It is a personal and a communal story.

Salh told Open Country Mag that her memoir was inspired by the multiplicity of her life. “I’ve lived a life that was quite different from that of many of my California friends and my children as well. Not many can say they grew up a nomad in a desert filled with wild animals, angry scorpions, snakes, and unforgiving drought.”

As a young girl, she moved through the vast open terrain in search of grazing land and water for her family’s herd of goats. “I still see myself standing on a tall termite mound,” she said, “looking into the unclaimed land of the desert, watching and listening to the whispers of my world. As the years passed, I felt a strong urge to bring my past to light for my children and the world.”

Those early years in the Somali desert proved to be formative for Salh. “Sitting under the moon and listening to the stories and poems that had been handed down for generations really made me the person that I am today,” she said. “It infused me with confidence, self-reliance, and resilience, and taught me the many lessons that come with an uncommon way of living. Even though I did not meet the heroes in those stories, I felt connected to them.”

She also wanted to tell her African story with truth and complexity. “Many times, I read books written about Africans by westerners who often lack the insight into the diverse background of Africa itself. Others then read these books and judge us through those lenses. For the past years, I have watched and felt a culture shift in America which is not favorable toward immigrants and displaced refugees, so I’m glad my book came out when it did.”

Kirkus Reviews called The Last Nomad “a clear-eyed and moving chronicle of her coming-of-age during a tumultuous time in the history of her native Somalia.” Publishers Weekly praised Salh’s prose which “radiates with deep empathy and sensitivity, a reflection of the gift for storytelling she inherited from her poet grandmother.” The book, the publication wrote, “stuns with raw beauty.”

The potential of stories is central in Salh’s memoir. “In this time of great misunderstanding, I think now more than ever, we have to share our stories,” she said. “Stories have a way of connecting us, creating room for understanding and seeing each other as fellow human beings.”