Gaamangwe Joy Mogami grew up with her grandmother, in a village in Botswana, with no TV. One day, visiting a rich neighbour, she found a book by Ngugi wa Thiong’o. “I read that book and it just changed my life,” she told me, “because I just never knew that you could enter an entire world through, you know, something written on paper. But I did, and I traveled the streets of Nairobi in that book, and I was changed forever and enthralled.”

Subsequently, she spent most of her primary school years in the village library and finished all the books. Every town her family moved to, she sought out the library and read everything she could. “I don’t think it was by chance that I saw that book,” she said. “But I just think that my soul was always meant to go find books.”

At 16, she wrote a story, and, at 17, began a diary. But she wasn’t writing about boys—Dear Diary, he liked me yesterday, he does not like me today—she wrote about ideas. Her mother, proud of her, printed the story into a booklet. By this time, she had read mostly American and British books, until she encountered a novel by a Ugandan. “It just really shifted me,” she said. It was an awakening. It was 2013, and she made the decision to read “everything Africa.”

She began publishing poetry. Her drama production screened at the National Theatre in Gaborone. The more she browsed African writing, the more she saw things that interested her, including a blog by Belinda Otters, a UK-based Nigerian who interviewed filmmakers and visual artists. “I remember reading that blog every single day, all the interviews,” she said. “One day I randomly just had this dream. It was a very little powerful dream where I was interviewing Musa, who is my beloved friend who has since transitioned, and when I woke up, I was, like, I should interview.”

Mogami interviewed Musa and found the process interesting. “I loved the way that it allowed you to go into someone’s world. The train of thought, the stream of consciousness, particularly in the context of whatever that story is, whatever the perspective of reality, experiences is. It just allowed me to see someone else’s perspective.”

With Musa, she noted how their different perceptions of writing were based on where they came from, she from Botswana and he from Zimbabwe, and that idea of being in conversation with other Africans activated her. “There is the nationality, and you see the human within them and just see how we are all the same. You also see how the history, the culture of the particular country where they come from, influences this human. I just fell in love with that whole thing.”

In 2016, she started Africa in Dialogue, a website that has since interviewed hundreds of creatives—writers, visual artists, musicians, filmmakers. It is a library of not only ideas but of feelings, guided by the understanding that “Africa needs to have an archive of the current.” The documentation of “experiences that are going on right now,” she told me, “has to come from African people, and it has to come from people who are working with memory, with culture.” Its first issue had Musa as visual director.

Mogami is a skilled conversationalist beside whom the Q&A is a shallow act. She matches the intellectual and emotional register of her subjects, going deep when they do and floating when they retreat from revelation. “We are interested in the essence of the writer or the creator,” she explained, “but also the essence of the creation, whether a book or a poem or a film or a platform. Like, why do we create? Where does this come from? What drives this creation? How have we been shaped by the places we were born in, the places we have lived in, the people we have loved. Through an interview, we are able to really go into the realm of memory, of history of culture, without kind of like the anxiety that comes with creating stories.”

There have been writers, initially flattered by the prospect of being extensively interviewed, who pulled away, fearing introspection. “I think it’s not everyone that understands that and not everyone was comfortable being that vulnerable and going to that essence, you know. So probably that’s why those people got scared and didn’t respond. You have the rare opportunity to have a deep conversation that is beyond, ‘Oh, this one happened.’ It’s their loss.”

(Mogami interviewed me in 2017—my favourite interview, actually—and we came away planning to collaborate on a conversation series with the continent’s literary curators. Caught up in “stuff,” we never did.)

One thing lacking in contemporary discussions of African literature, she suggested, is a lack of will. “Some people feel like we need to be defending how the world perceives us as either some kind of, like, inferior or the poorest continent with diseases and wars,” she said. “When we get stuck in these false identities and we keep writing over and over to disprove them, we only keep affirming to our consciousness that these identities are true. If our stories are always either assuming this or defending that, we will never ever go to the next frontier of creativity, of our reimagination of true African identities. So my frustration is how we keep reacting. I’m looking and waiting for the time where we read stories and we’re not even noticing that we’re reading stories about ‘African people’ because we’re just really telling human stories. Or we’re just exploring consciousness for the sake of exploration, not because we want to have something ‘important’ to say all the time. My job is to look at our separateness as people.”

Not only does Africa in Dialogue catalogue these offending and defending of identities, the magazine is also a response to how “writers were just dismissed in the role of culture or history of everything that we do for the human race.” And yet more than just archiving, it is driven by the idea of connection among African creatives, “bridging whatever gaps we need to bridge.” In the last few years, it has run an internship programme, an incubation for interviewers new to the form.

Mogami, who also works as a shaman, uploading videos on Facebook in which she discusses the ancestral and spiritual, told me that the two, being a shaman and being an interviewer, come from the same source. They are, she said, “about consciousness, about the evolution of the conscious, the expansion of it, but particularly the witnessing.” Her role as a conversationalist is “to witness people,” she said. “I’ve been incredibly moved by a lot of creations from young writers in Africa.”

Back when she was planning to launch Africa in Dialogue, only one of the eight people she contacted responded. What kept her was her understanding that storytellers needed support and her commitment to providing it. “It’s beyond interview questions,” she said, “it’s understanding that you are participating in a moment and that moment will be documented and other people are going to look into that moment. That is the vision, the idea of building a bigger support.” ♦

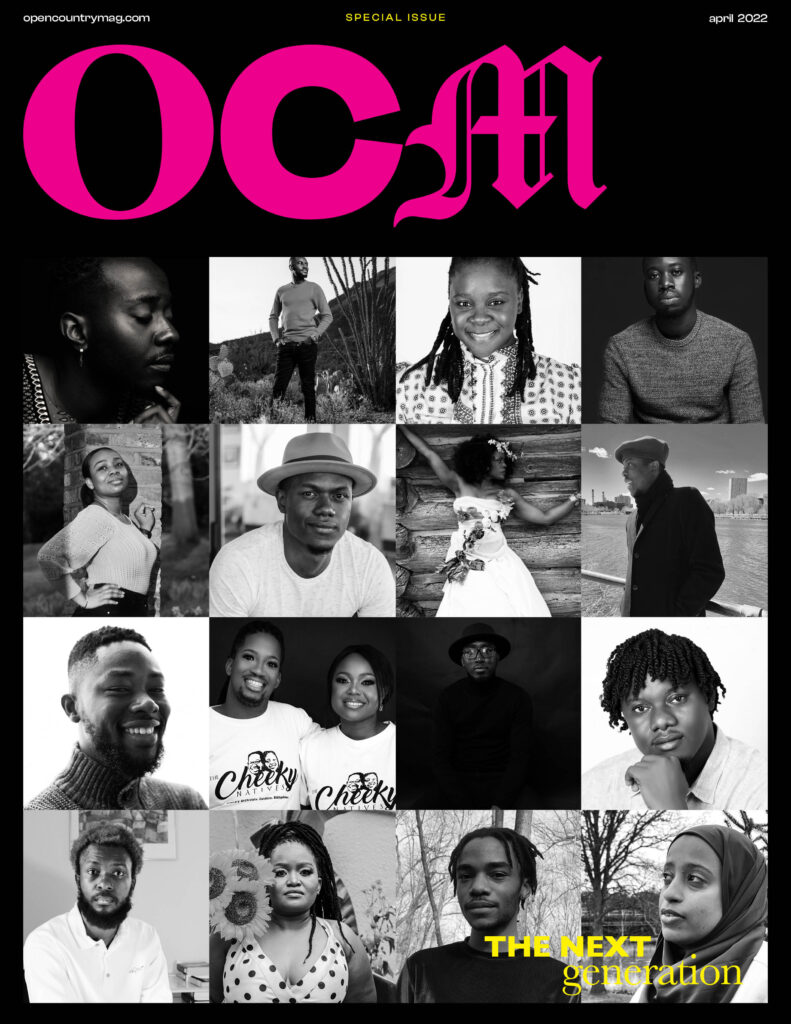

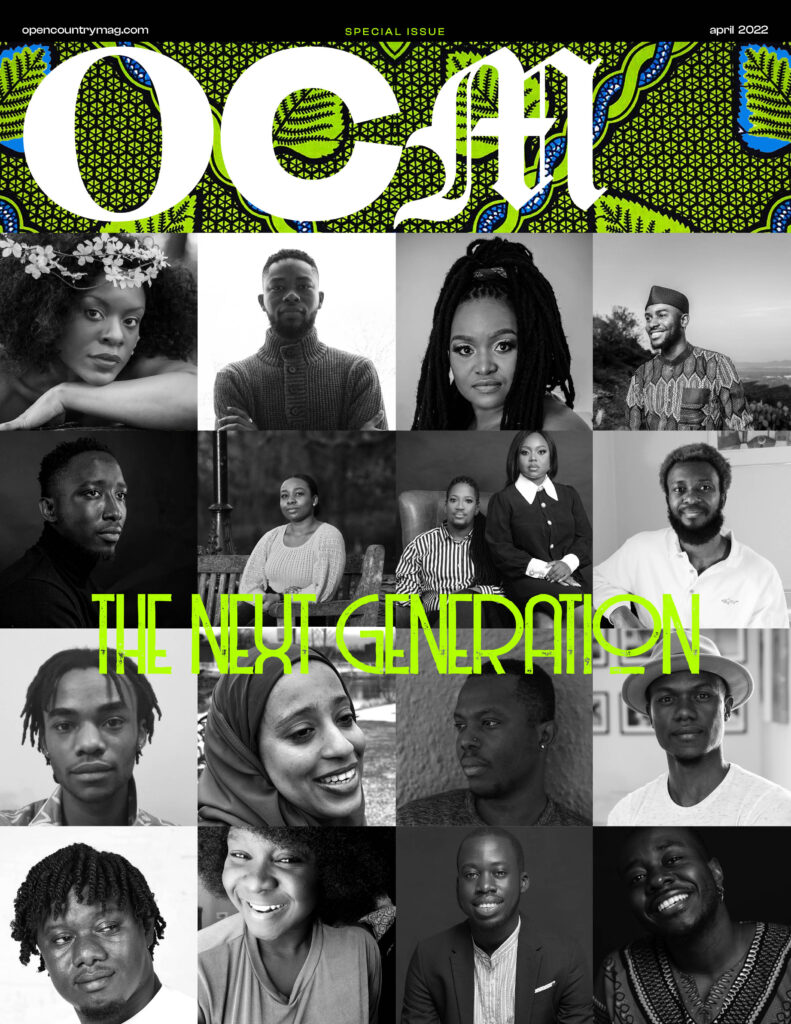

“At Africa in Dialogue, Gaamangwe Joy Mogami Lures Out Storytelling Truths” appears in The Next Generation special issue of Open Country Mag, profiling 16 writers and curators who have influenced African literary culture in the last five years, curated and edited by Otosirieze Obi-Young. The issue comes with two covers, designed by Emmimade Design Agency.

4 Responses

Power