As a child, Keletso Mopai loved her home. Even with their tiny kitchen and living room, asbestos roofing, outdoor toilet, wire fence, and two bedrooms for a family of eight, she did not think herself poor. In fact, she considers growing up in Lenyenye, a township in Limpopo Province of South Africa, the most memorable and impactful time of her life. As the family’s youngest, she was coddled, content, because her parents would give her change to buy sweets at the tuck-shop nearby whenever she asked; it did not occur to her that she could not go for school trips because her parents could not afford them and not because they were overprotective.

Her primary school also did not have a usable toilet, so she would go to the home of her mother’s friend who lived near the school just to relieve herself. She would see white children trot barefoot around the shopping mall. She would watch as Black people regarded white people with some sort of admiration.

At 14, she left Lenyenye for the first time, for boarding school, and discovered other cultures and languages, discovered that hers wasn’t recognized, that, as a Black person in South Africa, her language was not considered “a language.” She witnessed a woman in her township getting beaten on the streets by a man, both people she knew, as everyone looked on.

Although she knew even then that none of those were right, it was only when she began writing that she started to mull over them, to truly think about her country and understand why those things were happening.

Mopai cannot talk about the person she has become without mentioning her father’s role in it. She credits him for the way she views the world, how she thinks and processes everyday issues. “My father spoke to me about politics from a young age,” she tells me. “His politics to me often deviated from the norm, and he made me think wider and critically, without wanting to be ‘correct.’”

She recalls being bullied by a boy in their street, and her father holding her hand at their home gates the next morning before school, waiting for the boy to pass. After that, the boy never bothered her again.

Her love of stories came from him, too. She listened to his tales of the rabbit and the tortoise and of the granny with a long tooth, and retold them orally. At nine, she recited a poem at her oldest sister’s traditional wedding.

She did not start writing until 14, 15. And she did not envision becoming an author until her second year in university, studying Geology. Disgruntled with her studies, she sat up in bed one night and thought about what she wanted and didn’t want out of life. She decided she enjoyed storytelling.

Her family found out about her writing when she made announcements on social media. Still, they considered it a hobby and saw her as a geologist.

Then, in 2019, her debut collection of stories, If You Keep Digging, came out. One day, she saw her father reading it in his bedroom. Another morning, her siblings told her that he cried watching her interview on TV. That was when she knew she had made him proud. The rest of her family were also catching up to her dream, and when she decided to pursue an MFA in Creative Writing, they took her seriously. But only months later, a week before the lockdown began in March 2020, her father had a mild stroke and passed.

“He made me trust my own opinions and outlook on life,” she tells me. “And, I think, for one to be a writer, they need to put trust in their words and their pen.”

The stories in If You Keep Digging, most of them set in her Limpopo Province, were inspired by regular people Mopai has interacted with. Naturally, they highlight issues that South African youth grapple with—sexuality, racism, unemployment, colorism, mental health, gender-based violence. The book embodies her activism, she tells me, her irrepressible “need to defend the defenseless.”

She wrote “Skinned” imagining what it must be like to date as a girl living with albinism. “I wanted to depict her not as a victim but as a fleshed out human,” she explains. “I wanted to write her as someone who can make mistakes and hurt other people, too. I wanted to make sure that she was treated like other characters in that story. And whenever someone mentions that story to me, I wonder if they noticed that because I really didn’t want her skin to be the only focus.”

“Monkeys,” written after and interlinked with “In Papa’s Name,” stemmed out of her interest in exploring issues faced by white boys living on farm. Like with “Skinned,” she wanted the character Nicholas and his family to be realistic, “to reflect us as people and as truthfully and authentically as possible.”

She says, “My characters have to be relatable, accessible, and tell ordinary stories—not caricatures designed only to infer ideas to my readers.”

She set out to just tell stories but inadvertently distilled activism into her work. She listened to her readers, the questions they asked, the discourse that arose. “Telling stories because you want to address a particular issue could sometimes lead to an unrealistic and biased story,” she says.

Still, she acknowledges the power of literature, especially in her country. “South African writers, especially Black South African writers, have always known the importance of reflecting our times. There’s always been these wonderful writers that knew they had to write Black stories, from Phaswane Mpe, Sindiwe Magona, to Kagiso Lesego Molope and Niq Mhlongo. It’s because of our issues as a country that we know how much our stories need to be told. Stories can teach and entertain at the same time. There is so much power in that.”

It is why her activism remains important. Her own identity feeds into her storytelling: dark-skinned, she is subject to colorism; as a Black person in a racially divided nation, she is socially and economically affected; as a woman in a patriarchally constructed society, there are expectations heaped on her to behave a certain way.

Hers is a powerful perspective, but, she says, people like her do not have decisive power in a country so stratified.

“I feel that I will always need to worry about how I balance storytelling and activism,” she says. “And in my opinion, If You Keep Digging shows that I can.”

Mopai has always been interested in South Africa’s Post-Apartheid system. Reading Kopano Matlwa’s Coconut convinced her that she should be. She longs for a better country, especially for Black people, women, and children from poor backgrounds. While hopeful, she has come to terms with the fact that the country has a long way to go in tackling challenges.

“We could solve the alarming high unemployment rate today, but does that mean men will not abuse women, and that Black people will finally own a fair share of economic power?” she explains. “I hope we get to a stage where we see actual change or progress in a country that only became democratic in 1994.”

In coming years, Mopai hopes not only to write more books but also to teach upcoming writers how to write with authenticity about Africa. She does not consider herself an expert, she clarifies, but she believes she has learnt much, enough to know aspiring writers need guidance. And she wants to be that person for them.

“I feel as though we are currently taking the necessary steps with our limited resources,” she says. “I think young African writers are currently doing more important work in their respective countries and uplifting each other, and that’s what matters the most to me, really.” ♦

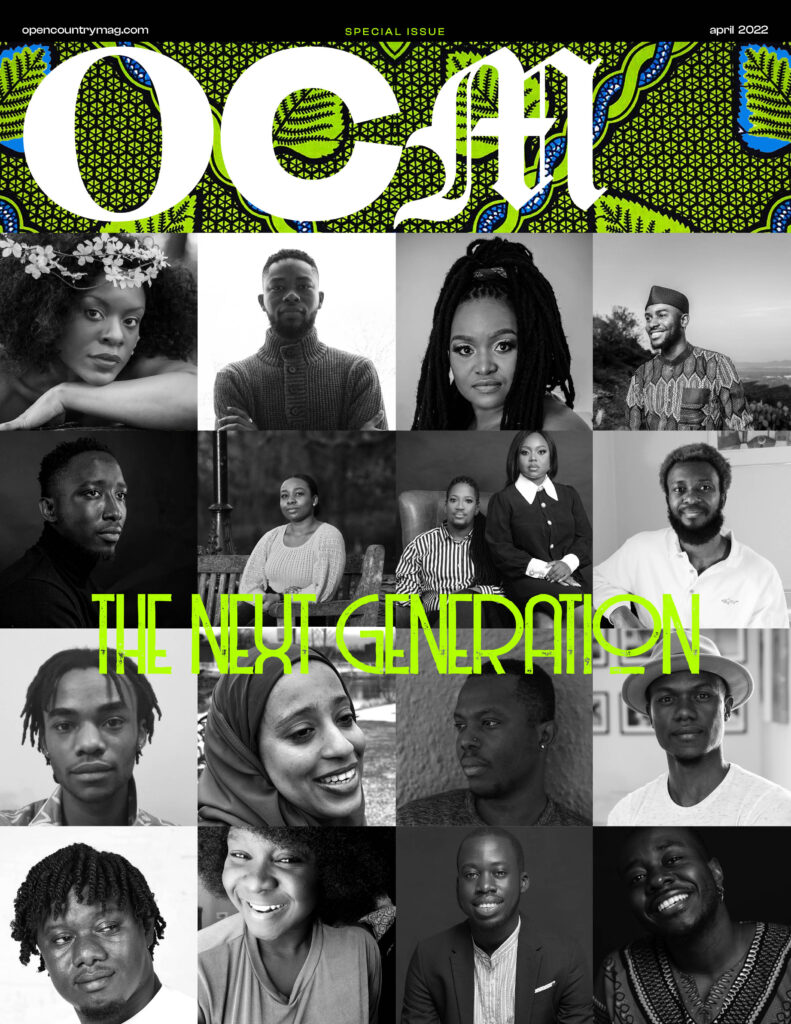

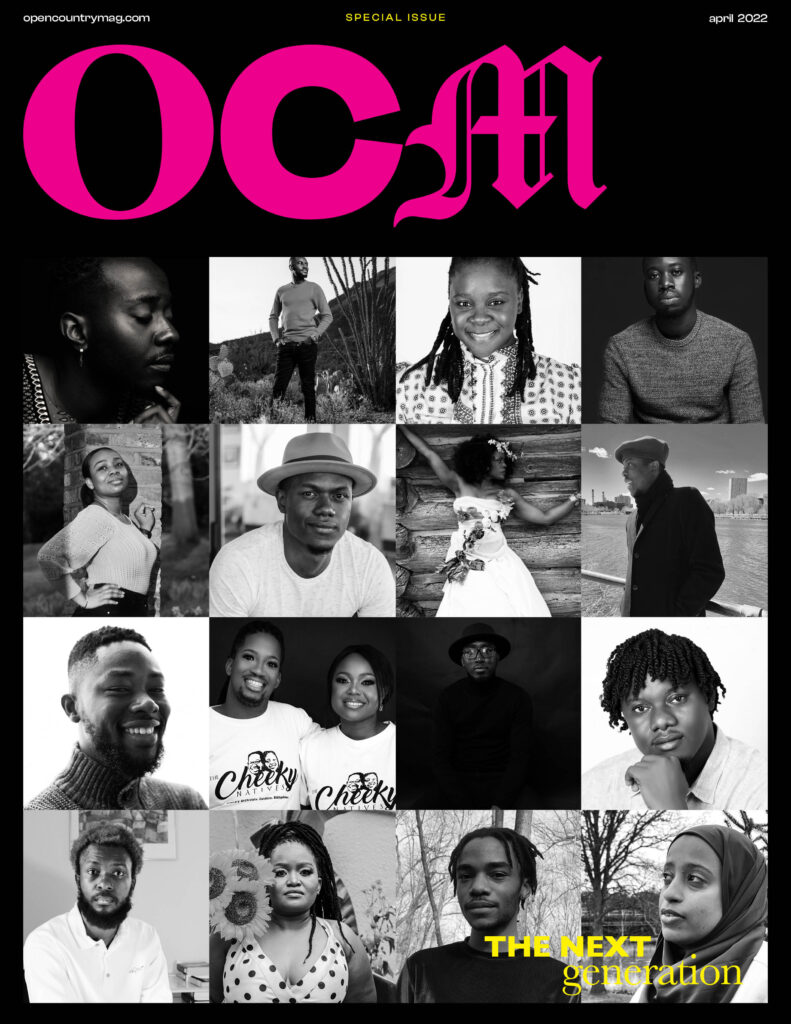

“Keletso Mopai Owns Her Story and Her Voice” appears in The Next Generation special issue of Open Country Mag, profiling 16 writers and curators who have influenced African literary culture in the last five years, curated and edited by Otosirieze Obi-Young. The issue comes with two covers, designed by Emmimade Design Agency.