Chinny Ukata and Astrid Madimba met during an internship in 2015. They lived together at the time, bonding over their mutual love for documentaries and history, and remained in touch afterwards. Before they met, they had both been dissatisfied with their little exposure to African history growing up in the UK.

Ukata, British Nigerian, sensed a vacuum in her education when she learned there was more to Britain’s role in the Biafran War, and then her father’s stories of his experiences sent her researching more. Madimba, British and Congolese, struggled with her identity, and began searching for a deeper connection to her Africanness and her country, the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Late one night, after Madimba’s rant about a bad date at an African art exhibition, she and Ukata sat and planned a podcast retelling African history. Then they signed up for a podcasting masterclass.

It’s a Continent launched just before the lockdown in 2020, but has since been played in classrooms across Europe and listed as one of the best African podcasts by the Guardian, racking up an average of 4,000 downloads a month and breaking into Apple’s Top 25 history podcasts.

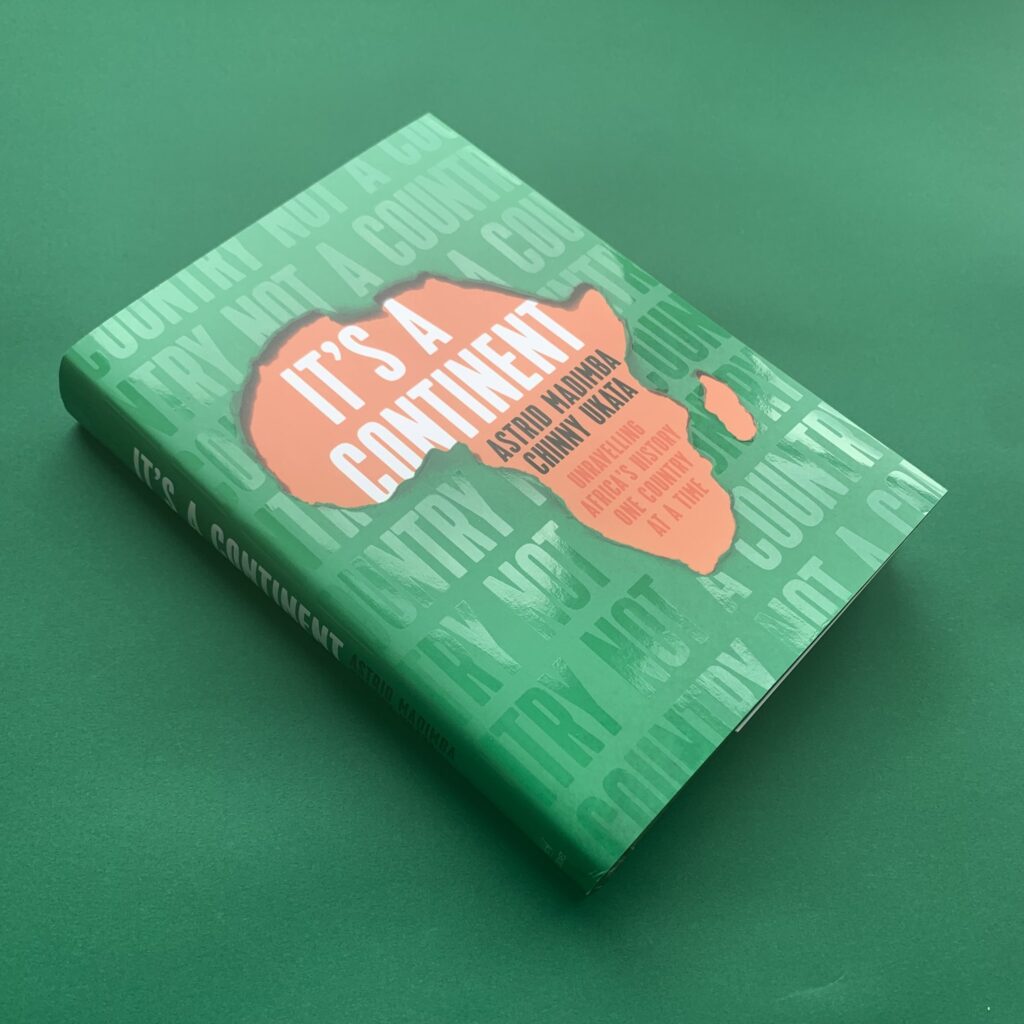

This July, it was published as a book by Coronet. Ukata and Madimba say that they hope for it fill gaps in school curriculums in the UK. The two podcasters spoke to us about their journey.

It’s a Continent celebrates Africa’s rich histories and sheds light on injustices in perceptions of the continent. What particularly inspired it? And how did you two, a Nigerian woman and a Congolese woman, decide the angle of conversation?

This journey started for us in March 2020. Since launching the podcast, it has resonated with many people. We’ve received messages from listeners across the world—the UK, Taiwan, South Africa, Nigeria, Uganda, and many more. The podcast was inspired by our wanting to learn more about Africa’s rich history, and we wanted to share these learnings with others who also faced a similar challenge. With this focus in mind, we made sure the content was accessible and easy to follow, providing listeners with a starting point to discovering Africa’s history.

You’ve described the book as a continuation of the podcast. Why was it important for it to take a textual form? How would you describe the process? Was it as simple as transcribing your content?

We script our podcast episodes to some degree, so an equivalent level of research was required for the accompanying book. However, the flexibility of the podcast allows us to be reactionary. We can cover topics discussed in the news and curate content with suggestions from our listeners.

The importance of moving to a book ensures our content remains available and plays a role in ensuring African history is documented. We know that many of our histories are of the oral tradition; as a result, some aspects have been lost—as they say, When an Elder dies, a library burns to the ground.

Some stories, we’ve previously covered on the podcast. But in other instances, we researched additional content to ensure we had a good representation of pre-colonial times, independence movements, and modern history. We touch on pre-colonial figures such as Angola’s Queen Nzinga, Samory Touré of Guinea, and Madam Yoko of Sierra Leone. We also recognise Africa’s contribution to the modern world in Kenya’s Wangari Maathai, Burkina Faso’s Thomas Sankara, and South Africa’s Steve Biko.

Comprehensive written material on African History is not widely available for free. How did you fare in researching for your podcast and book? What challenges did you face, and how did you overcome them?

The most challenging part of hosting a podcast and writing a book has been managing these two spinning plates whilst also having full-time jobs. At times we had to research different topics for the same country and carry on recording and producing. We also faced barriers when accessing specific resources, some of which were costly or required translation.

We didn’t necessarily feel pressure as we wanted our voices loud and clear in this book. It’s a rarity to see two African women write on the topic, as this is usually reserved for European men. They say history is written by the victors, but this is what leads to inaccuracies and not accounting for the true picture of what happened.

“Why is Africa still perceived as a country when there are around 2,000 languages spoken on the continent alone?” the book’s description asks. With the amount and quality of art, including literature, film, and music out of the continent, why do you think this misconception largely persists in the West?

It’s a persistent stereotype that has endured out of ignorance and, to some extent, racism. The image of the African continent seen in the West still hasn’t moved forward since the days of Live Aid, with some people still homogenising the continent and believing it is a place rife with poverty and loss. This also comes down to not understanding complexity—most countries are less than 70 years old.

However, we now see cultural exports from the continent in the form of Afrobeats, Amapiano, Nollywood, and engaging writers. Hopefully, this is the beginning of the world recognising what Africa has and continues to give.

Your publisher describes It’s a Continent as a “history book for non-historians,” without the “academic jargon.” Tell us more about this.

The use of academic jargon is one factor that makes [history] materials challenging to access. Another critical factor is that some resources, such as journals and books, can be costly.

Our conversational approach to the book and podcast allows us to reach audiences who wouldn’t typically engage with such content. For example, many people don’t have fond memories of history lessons, and we want to ensure Africa’s histories are presented in a way that piques interest.

In some African countries, history is ignored in academic curricula. Africans, both in the continent and in the Diaspora, while aware that the continent has a rich history, do not know much of it. What do you hope for your African readers?

While conceptualising the podcast, we realised that neither of us knew about the histories of other African countries aside our own. So we hoped to bring in a Pan-African historic piece, too, and see what we can learn from the stories of other African countries and how they connect.

It’s a Continent provides a starting point for learning about African countries. Readers will gain a better understanding of how African and European histories are intertwined beyond colonisation, the roles African women have played in different countries, and an appreciation for this relatively youthful continent where many countries have only been independent for just over 60 years. We hope these stories resonate with readers and encourage them to continue discovering, because Africa’s history is everyone’s history. ♦

Buy It’s a Continent. Open Country Mag may earn an affiliate commission from Amazon.