Nana Nkweti started writing at nine years old. A sci-fi lover even then, her earliest stories saw her in future worlds, going on space adventures. Like most writers, she was a voracious reader, digging through her father’s books, the good fortune of having a home library. She read everything from fantasy to the realist classics, and began to imagine herself and girls who looked like her reflected in those stories.

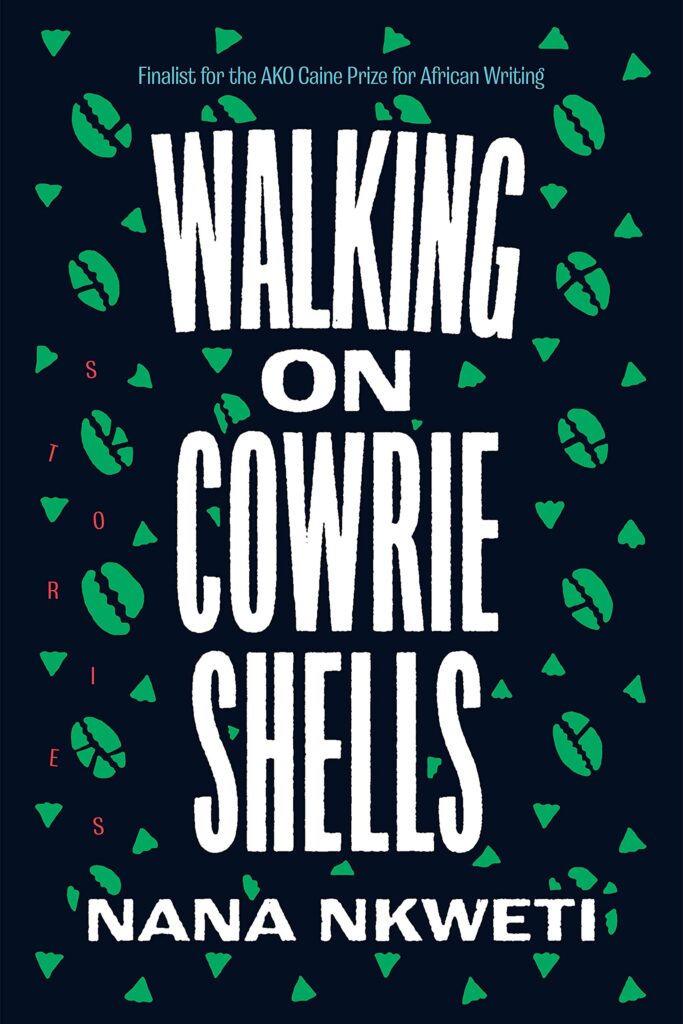

It is no surprise then that the 10 stories in her collection Walking on Cowrie Shells, which days ago won her a Whiting Award, centre Cameroonian women. The characters share her intersectional identity, as a Black woman, a hyphenated American, an ethnic African. But the stories also speak to the universal idea of people charting next steps, growing and evolving along the way.

The title “Walking on Cowrie Shells” is a play on the English idiom. She deploys it in the book to embody that sense of being in a threshold, in liminal spaces, of teetering between choices, between cultures or identities. Her characters are tentative; they are about becoming and figuring life out, who they are, who they want to be.

The prose is often colourful, flitting between realism, magical realism, YA, sci-fi, and myth, between tones and voices, with languages from Ebonics and Africa to Franglais, all untranslated. The book’s disregard of the neat lines of genre has been lauded.

In “It Takes a Village Some Say,” a shrewd teenager is unapologetic about taking advantage of her adoptive family. In “It Just Kills You Inside,” a zombie outbreak hits Africa and a world-weary crisis manager is hired for media control.

“Rain Check at MomoCon” sees a teenage girl who aspires to be a graphic novelist—a far cry from “the high holy trinity of professions blessed by African parents,” law, medicine, and engineering—attend Comic-Con at Javits Center with her frenemies. One of the stories is arranged as the changing hairstyles of a Black woman and another is about a mami wata.

Nkweti’s dynamic style is not a mere gimmick; the book reflects her “eclectic interests.” They include being feminist and being a Black nerd—a “blerd,” as she puts it. Then add her motley of literary tastes and her developmental years in Cameroon and the US, where she first arrived to study international law and nursing.

“I do contain multitudes!” she laughs. “I feel like the short story allows us to explore those multitudes. You have to know what animates you as a writer. I know what gets me juiced up and I have to honor that because I have to enjoy the writing. Especially when you’re writing a novel because you’re doing that for a long time. You have to stay engaged. You have to stay engaged.”

She chuckles, as she does during much of our Zoom call. “People are hungry for experimental forms. People want to see something new. People read my work and say, ‘Oh, is this the same author two pages ago? Is this the same [character] I was encountering in that world?’ When they see that and recognize that, I think they respond to that. And I’m happy they do. It’s not me trying to be, like, ‘Oh, look, look what I can do!’”

She deems short stories her forte, and the next step, she knows, is bringing the exuberance of her collection to her novel-in-progress.

Some of the stories in Walking on Cowrie Shells are older than a decade. Nkweti wrote “Kinks” after a particularly difficult break-up, and “It Takes a Village Some Say,” an attempt at apologia, at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Some were written more recently, but all were imagined over time. She is excited talking about every story, but choosing a favorite, she says, is like picking a favorite child. While each presented challenges and joys, some were harder to write, like “It Just Kills You Inside,” which goes back and forth in time.

“Structure doesn’t come naturally to me,” she says. So she had help from her editor at Graywolf Press, and a community she credits. “I love the feeling that all of them would hang together in a collection. I was very fortunate that my publishers could see the motifs and recurring themes so that they fell into place really nicely.”

Nkweti was caught in the weird experience of having her first book released during the COVID pandemic. Her book tour was primarily virtual, her readings done in a backdrop of a book wall in her home in Tuscaloosa, where she is assistant professor of English at the University of Alabama. Not being able to interact with her readers as much as she’d like to made it all feel apart from her sometimes. Coupled with her busy schedule, part of her feelings have been muted.

“Writing is very solitary,” she tells me. “It’s like you’re in your little bunker, hunkered down, writing stories and playing with your make-believe friends and it feels very isolating sometimes. But when you’re sharing that as an author, with people in the world, it makes them feel more real.”

Still, she appreciates the engagement of her readers, and is fascinated by their perspectives and interpretations. A New York Times review, by the American author Deesha Philyaw, asks: “Is there anything Nana Nkweti can’t do?”

“Hopefully, no!” Nkweti says. “Hopefully, I will just keep on trying new things and enjoying them and having readers enjoy them with me.”

On the African literary scene, Nkweti is proud of the work that’s risen in recent years, of the multiplicity of voices, and especially that there is an African sci-fi prize organisation: the Nommo Awards.

“When I was growing up, this stuff did not exist,” she says. While she wants to win all those “fancy awards,” she notes that not every book has to be some great literary opus. “What I hope to do in my own writing is to continue to be part of making space for all types of different African writing. I’m going to do all that literary stuff because it’s natural to me, but I do love a good crime story and I do love a good zombie apocalypse story.”

She continues, “I want for all our writing to be represented. I’m just part of that chorus of African voices that’s come up from the continent in writing across genres and writing what we want to write and showing a diversity of experiences both on the continent and the diaspora.”

Nkweti is a part of Cameroon’s new literary generation, coming of age amidst the country’s Anglophone Crisis. Since Imbolo Mbue’s 2016 novel Behold the Dreamers, which got a million-dollar advance, Cameroonian literature has earned more notice. In 2019, Nkweti herself became the first Cameroonian to be shortlisted for the AKO Caine Prize. Bakwa, the country’s only Anglophone publication, has in the last 11 years curated literary and arts writing and nudged new writers into visibility. Nkweti, set to work with the magazine on workshops in the future, applauds the work of its founder and editor Dzekashu MacViban.

But she wants more. Like is the case with Nigeria, she says, she desires a deep literary well, and for Cameroonian literature to gain notability on the world stage. “That’s all I want,” she says, “more and more and more.” ♦

“Nana Nkweti on Crossing Genres and Writing Cameroonian American Experiences” appears in The Next Generation special issue of Open Country Mag, profiling 16 writers and curators who have influenced African literary culture in the last five years, curated and edited by Otosirieze Obi-Young.

3 Responses

Haven’t read Walking on Cowrie shells but will definitely add to my book lists this summer!

Just walked into a gold mine!!! I read the ‘unputdownable’ novel ‘BEHOLD THE DREAMERS’ by Imbolo Mbue; itchy to lay my hands on Nana Nkweti’s short stories.