On a cold morning in September 2018, Hannah Chukwu walked into the office of one of London’s oldest publishing houses, Hamish Hamilton, the Penguin Random House imprint that launched the careers of R. K. Narayan, W. G. Sebald, and Zadie Smith. It was the first day of her six-month editorial traineeship, fresh out of an English degree at Oxford, and she had little hope of securing a job there.

“I was nervous about coming down to London, knowing how expensive it was,” she tells me on our Zoom call three nights ago. “I thought, I don’t know anything about publishing and whether I’ll be any good, but it’s six months, and if I can’t handle London, or I don’t end up getting a permanent job, I’ll leave.”

Hamish Hamilton (HH) was founded in 1931, and, having developed a coveted list that included Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Satre, J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, and Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, Penguin Books acquired it in 1986, where it remained until Penguin’s 2013 merger with Random House.

For over 20 years, HH has been led by the editor Simon Prosser, who published Kiran Desai’s Booker Prize-winning The Inheritance of Loss, and has seen the imprint’s sales grow year by year. In May 2018, he was named Editor of the Year at the British Book Awards.

“Oh my word,” Hannah recalls her trepidation meeting Prosser. “Obviously, he’s the best of the best and I was a bit scared. But he was the loveliest man, he’s so generous, so, so kind, supportive of everyone, really, but especially of people from underrepresented backgrounds.”

With Hermione Thompson, who’d joined from Viking in 2015, as her line manager, Hannah quickly settled in, and at the end of her six months, HH offered her the job. She was surprised. Since its founding, HH had only had two people in the editorial team. It was the imprint’s first expansion.

When Hannah joined, HH was in the editing stages of a new manuscript by Bernardine Evaristo, whose previous fiction books—prose and experimental novels set across places and times—had been published by the imprint for nearly 20 years, to respectable reception and varying, mid-list sales.

But the new manuscript felt different; it reiterated Evaristo’s formal innovation, this time as unpunctuated verses she called “fusion fiction,” in telling the stories of 12 Black British women of different ages, backgrounds, and sexualities. Some of the characters were young, around Hannah’s age of 22, and HH invited her to join the editing process. Hannah met Evaristo and, both Black and Nigerian British from similar class backgrounds, they bonded.

The novel, Girl, Woman, Other, would win the Booker Prize in 2019, top bestseller lists in 2020, elevate Evaristo, the first Black female and Black British winner of the prize, into an industry titan, and become one of the big career crowning stories of the last decade. It would bump up HH’s annual sales by 14.5%, its best figure in the last 10 years, and, just early this week, help earn Hannah a promotion from Editorial Assistant to Assistant Editor, and Thompson to Commissioning Editor.

“Simon let me have a voice in that campaign, have opinions,” Hannah says. “It’s really amazing that he gave me that kind of opportunity.”

Hannah Chukwu’s quick rise in publishing is in stark contrast to her father’s story. “My dad had a very typical Nigerian story,” she says. Educated in Nigeria, John Chukwu qualified as a doctor and arrived in the UK in the early ‘90s, only to be told by the NHS that he was underqualified to practice in the country. He had to start again, working low-wage jobs to put himself through a second round of medical school.

In a church in Edinburgh, where he was a pastor, he met a Scottish woman, Carolyn Pullar, a children’s worker. They moved to an estate in South East London, where they had Hannah, in 1996, and her two younger siblings.

Over the years, as he saved money, attended courses, exams, and cycled through jobs, the family moved around: up to a small village in Scotland near their grandparents, and finally to Manchester, where her parents are now based, her father a doctor, her mother a counsellor.

“Their story on its own is kind of amazing, coming from such different backgrounds,” Hannah laughs. “It was a very long, challenging path for them to get to where they are now.”

Hannah has been to Nigeria just once, in 2007 when she was 11, visiting her father’s Igbo hometown, Alayi, in Abia State. “We spent a month during Christmas, the Harmattan,” she remembers. “We also went to Lagos. I had an amazing time but I was too young to grasp what it meant to be seeing my roots.”

The Chukwus, like many Igbo families, are spread across countries: Nigeria, Ghana, the US, the UK. “We have this huge family WhatsApp group and we were planning a reunion that had to be cancelled because of the pandemic.”

Growing up mixed-race in early 2000s London—which now has a non-White population of 40%—meant she didn’t immediately encounter race as a barrier. “I have a unique experience because of all the places I’ve lived in,” she says. “I don’t remember feeling different.”

Except one time in a small village in Scotland. “My family was one of the only non-White families there. I remember the other children asking about my name, my hair.”

It was, she says, “the only time I felt uncomfortable about the colour of my skin as a child.”

Her English language teacher, in the state school she attended in Manchester, encouraged her to apply to Oxford—unusual for state school teachers who would rather not see their young, hopeful students deal with likely rejection so early. Hannah applied, and got in to study English and Literature. It was there that her eye-opener about race came.

“I was the only Black person in my year, one of few in my whole college,” she tells me. Until then, “I hadn’t really thought of myself as having those barriers.”

Later, the 400 students of her campus college, Worcester, elected her their president: the first woman of colour, and one of the only women ever, to hold the position. On staff and governing boards, where she was often the only woman, only Black, or only woman of colour, Hannah advocated for issues of access, equality, and diversity.

“Amazingly since then,” she says, “we’ve had another woman and then a Nigerian as president. So there’s been a lot of progress.”

After Oxford, she joined the charity NCS The Challenge, where she worked with young people aged 15-17. As youth leader, she guided the teenagers in stepping out of their comfort zones and finding their voices.

This, she found, was what she loved: helping uplift voices that aren’t always heard.

In early 2018, she came across an advert: the publisher Penguin UK had a talent-spotting scheme for editorial traineeships. Its imprint Hamish Hamilton had participated for years, and the opportunity was open to people from underrepresented backgrounds. Hannah applied and got in.

It was “the path that made the most sense to me,” she says of her state of mind then. “Reading was my favourite thing. I knew I wanted a creative job. I loved writing but didn’t really know about publishing. Without the traineeship, I wouldn’t have known publishing was a viable industry.”

During her traineeship, Hannah worked on Black Leopard, Red Wolf, the first novel in Marlon James’ Red Star trilogy. Three years earlier, James became the first Jamaican and openly Black gay winner of the Booker Prize, with his third novel A Brief History of Seven Killings, a book of intense realism.

“I loved working on a novel that was in such a different territory for him,” Hannah says in excitement, “how he shifted his focus to fantasy, looking into this rich history of Black writers writing fantasy and science fiction.”

Being offered a job here was, she says, “incredibly flattering.” It was HH, after all, publisher of activist voices like Arundhati Roy and Noam Chomsky. “I was looking around and I just felt I can’t imagine anywhere else I would feel the work was so important. I couldn’t really believe I managed to find something that aligns exactly with the things that I cared about the most.”

Hannah is also an editor at HH’s literary magazine Five Dials, created as a platform for early literary talent. At Five Dials, the HH team works with the Canadian editor Craig Taylor to produce interviews and features, spotlighting exciting writers.

After Evaristo’s Booker Prize win, the HH team had a big meeting to know her plans, if she had anywhere she wanted to put her spotlight on. One result of that meeting is “Black Britain: Writing Back,” a project bringing back overlooked Black British authors. “Many of the writers who came up alongside her, writing in the ‘80s and ‘90s, their books have completely disappeared,” Hannah says. “They never got the support they deserved, struggling with placement in bookshops, struggling to get publicity. Bernardine thought: ‘I could have been one of those. I want to do something to acknowledge it.’”

It was also an issue that Simon Prosser had been thinking about. In 2000, he published an anthology, IC3: The Penguin Book of New Black Writing in Britain, co-edited by Courttia Newland and Kadija Sesay and featuring almost 100 writers including Evaristo, Buchi Emecheta, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Lemn Sissay, and Jackie Kay. But the book struggled to get publicity.

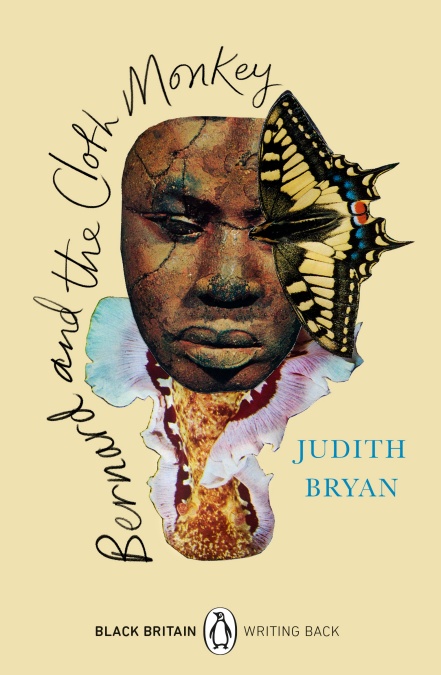

For “Black Britain: Writing Back,” they selected six books for Evaristo to introduce: Jacqueline Roy’s The Fat Lady Sings, CLR James’s Minty Alley, SI Martin’s Incomparable World, Mike Phillips’s The Dancing Face, Nicola Williams’s Without Prejudice, and Judith Bryan’s Bernard and the Cloth Monkey.

HH was deep into the project when the killing of George Floyd in the US forced a global surge of the Black Lives Matter movement.

“At the start of the project, I had been worried the books wouldn’t land, that no one would care,” Hannah remembers, “and then all these conversations about our history, our statues, and what institutional racism looks like. Bernardine was a talking head focus, always on TV talking and leading the conversation.”

Later, Hannah says about Evaristo: “She’s changed everything. She’s used her platform to amplify Black voices and young voices and queer voices. Every opportunity she has to uplift people, she does use.”

Penguin UK, in response to increased calls for diversity in publishing, announced Lit in Colour, a campaign to decolonize the curriculum. “We thought of our role at Penguin, influencing the canon, what people are reading, what the English curriculum looks like for young people in the UK,” Hannah explains.

“We commissioned research with the Runnymede Trust to find out the specific problems and think about how to address them. The campaign found there was only one novel or play by a Black person on any of the English GCSE curriculums—which is shocking. The first step we’ve taken in the campaign is to make teaching resources available for books by writers of colour.”

Another HH author, Avni Dosh, whose debut novel Burnt Sugar was a Booker Prize finalist last year, joined Evaristo to make videos for the campaign.

Hannah’s new Assistant Editor position means even more responsibility. She joins a small pool of African editors working to diversify UK publishing, including Ellah Wakatama at Canongate, with her track record at Jonathan Cape and Granta, and Ore Agbaje-Williams at HarperCollins imprint The Borough Press, who has teamed up with Afreada editor Nancy Adimora to curate Of This Our Country, a forthcoming anthology of essays by leading Nigerian writers.

“With ‘Black Britain: Writing Back,’ the idea is to remap our history, rewrite the history of our nation and diaspora, tell the story beyond the limited way it has been told in the UK,” Hannah says. “You have Carribean voices, African voices. Getting to use my voice as a young Black woman to influence these amazing books we’re working on—this has been a dream.” ♦

Black Britain: Writing Back launched on 4 February 2021.

More Essential, In-depth Stories in African Literature

— How Tsitsi Dangarembga, with Her Trilogy of Zimbabwe, Overcame

— With Novels & Images, Maaza Mengiste Is Reframing Ethiopian History

— Nigerian Literature Needed Editors. Two Women Stepped in To Groom Them

— How Lanaire Aderemi Adapted Women’s Resistance into Art

6 Responses