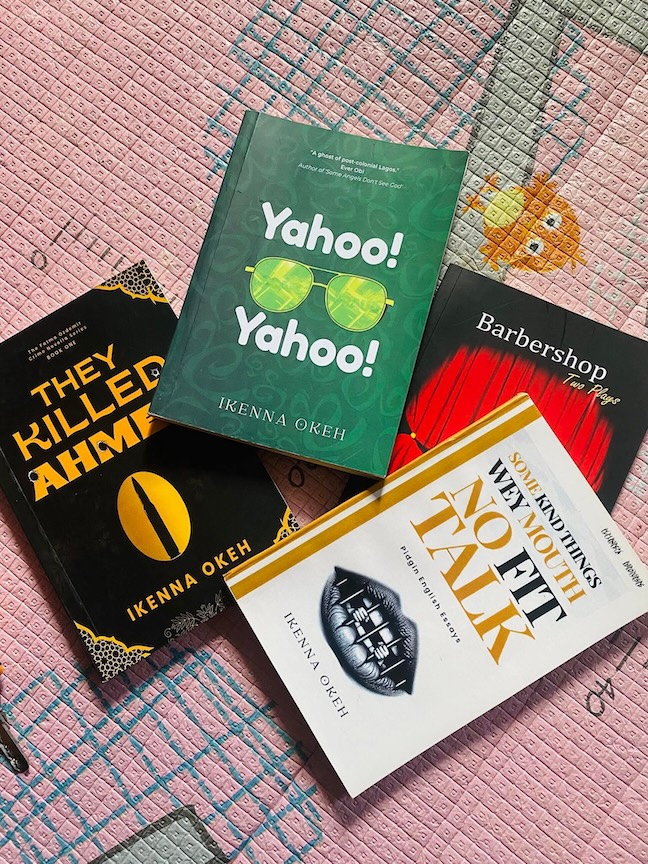

Halfway into the initial draft of his novel Yahoo! Yahoo!, Ikenna Okeh could not continue. The third-person narrative voice sounded wrong, stiff, judgmental, like it came from outside a mind whose language he did not speak. “A scammer, like a politician or a law enforcement officer, is a human being, a product of society, and it would be unjust to depict them without attempting to be impartial, at least,” he explained. He abandoned the manuscript and began again. He wrote in the first-person, personalizing the character. He toyed with assuming the life of a scammer. He reached out to people with questions, then had to convince them that he was not planning mischief, that he was only a writer seeking to tell a story with precision. It was, he believed, the only way he could tell the story.

Okeh did not have to imagine much. The title of the book, “Yahoo! Yahoo!,” is the popular Nigerian slang for Internet fraud, a term that dates to the late 1990s when cybercafes began sprouting across the country. By the 2010s, that criminal subculture had grown too loud and sophisticated to ignore. The evidence was everywhere: on the streets, in songs pouring from bars — songs he works into the general rhythm of the story. The novel is partitioned with Nigerian pop music lyrics. They are songs — Olu Maintain’s “Yahooze,” 9ice’s “Living Things,” Kelly Hansome’s “Maga Don Pay,” Zlatan Ibile’s “10 Bottles” — that became anthems of the Yahoo Yahoo subculture. But Okeh is not interested in blaming anyone. Like him, those musicians were responding to society in the truest way known to them. “As artists, we owe it to ourselves,” he insisted.

Okeh, whose novels are rooted in contemporary culture, told me that Nigerian literature has always maintained a snobbish stance about certain aspects of our social reality. “Maybe we should begin to consider the possibility that Nigerian literature is so fixated on the politics of identity that it is progressively going out of touch,” he said. “I think it is high time we changed that.” He wants to empower a new narrative, and his novel is a “mirror” for a dark world that society enables. In Yahoo! Yahoo!, there are characters who record themselves masturbating, who smoke weed and have rough sex; characters who steal from the needy, commit identity fraud, and afterwards thank God for a successful operation.

“The character of Chidi is one that I whipped out of the air,” he said. “It is no surprise that he feels real. It is high time we made literature more relatable, entertaining, and mainstream. We need to get serious as Nigerian writers, not writing about flowers at war time.”

His realism has startled some readers. My friends who read the book joke that the author must have “run a hustle” himself, a sentiment I shared before learning his process. “There is nothing about how a HK runs that can’t be gleaned from social media skits,” Okeh said, referring to another slang — Hustle Kingdom — for digital scam enclaves. Street philosophies are loud in Yahoo! Yahoo!, a reflection of how deeply fraud has eaten into Nigerian life. “Na yahoo yahoo wey all of us dey do for this country,” says Chidi’s sister Chekwube, who flaunts expensive wigs and an iPhone 14 Pro that her brother suspects were given to her by the men she’s “sleeping around with.” At a club, Chidi meets Billy of Asia who tells him that Westerners and Asians are even bigger fraudsters than Nigerians; the only difference is that Nigerians are loud about theirs.

Okeh does not disagree. He points to government institutions: foreign missions that do not defend Nigeria’s image, an EFCC [Economic and Financial Crimes Commission] more interested in spectacle than justice. “Yes, scammers need to pay for their crimes,” he argued, “but when the EFCC abducts a suspected scammer, confiscates and sells their properties without returning the proceeds to the victims of the said scam, has justice been served? Justice isn’t served when a pirate raids a thief.”

Okeh’s moral concerns don’t end on the page. They extend into the choices he makes as a curator. He is director of the Puebla International Literature Festival, which, last year, was enmeshed in controversy. The festival had selected South Africa as its 2024 Country-in-Focus, but when yet another round of xenophobic and anti-Nigerian backlash flared in the country, it withdrew that designation, in solidarity with Africans who had been attacked in the country. That decision started a fire that burned beyond literary circles. Some observers called it audacious; others saw it as divisive. The South African Department of Arts and Culture issued an antagonistic response.

Okeh told me that it was an uneasy decision, and he did not make it in a haste. He’d resisted the suggestion until it became “horribly embarrassing” to ignore. What unsettled him was the brazen irresponsibility of the South African government in an issue that endangered the lives of other Africans.

The festival had not offered public dialogue with South African writers before disinviting them. “It wasn’t necessary,” Okeh said. To seek dialogue would have meant cornering their South African counterparts into a forced reckoning they had already chosen to avoid. What mattered was clarity of action, not negotiation. It came at great cost, financially and emotionally, but it was the only way to remain honest to what the festival stood for: engagement with the world, not escape from it.

When I asked if he sees that moral stand as an extension of the interrogation in his fiction, Okeh resisted the suggestion. “I am afraid to project myself as a moral crusader,” he replied. “In fact, I am not. I’m just a man who had to do what he had to do, with what he had.”

Fictional characters are not people, and if Okeh sets up his to feel like they are doing what they have to do, he also keeps them leashed. Yahoo! Yahoo! ends with a moral clarity that certain readers might welcome — readers who like stories with sharp edges and need their fiction to close with meaning — but that others might question. I am less drawn to societal critiques that resolve into “lessons”; I prefer stories to be untidy, the way life often is. Yahoo! Yahoo! does not allow that open-endedness.

This quest for fictive meaning is not new territory for Okeh. His 2017 debut, A Tale to Twist, is a narrative verse about an enslaved woman who returns home. He has explored survival and identity in his novels since. In Rogues of the East, a struggling writer accepts to help a benefactor locate an estranged son and is lured into a kidnap-for-ransom deal gone sour, involving a ruthless cult leader and a vengeful hit man. The novel was translated into the French. Another, Deportee, the story of a man deported from Northern Cyprus, was longlisted for The Island Prize in 2022.

But Yahoo! Yahoo! is a leap: not an observation of survival from the outside, but an inhabitation of it from within. It needed a Lagos character like Billy of Asia, someone about whom, Okeh puts forward, “one could see how violence and mayhem threatens our social fabric.”

Okeh does not plan his fiction. He writes spontaneously until the entire plot unfolds. Structure stifles him. And he is prolific, with over 10 books in under a decade, and just as many unpublished manuscripts. Friends call him a workaholic. He admits to burnout.

“Being the first son of the kind of family I come from has its challenges, especially now that my father is no more,” he said. “There are decisions to be made, adults who get out of line, the demands of traditions and rites. These things take their toll on the mind and on one’s resources.” And then there is the challenge of being a “Nigerian writer,” always writing against silence and scarcity.

To survive it, he walks, he hikes, he eats well, he travels. He reads. Once, reading Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, he found a passage that, he told me, conveyed eroticism without vulgarity. It changed him. “I told myself that if Toni can achieve this in one passage, I could do the same in an entire book.” The result was last year’s Whatever Happens in Antalya, in which a young Nigerian man and an older French woman begin a risky romance in the titular Turkish city.

Okeh told me that he wants to wrestle away from inauthenticity in fiction; that, on a personal level, would be his prime achievement. If he writes about a thief, he wants readers to suspect him of stealing. If he writes about a priest, they should wonder if he has been one. And as he writes about his country, he hopes that readers see how writers are tracing society with accuracy and indiscrimination.

“My stories are not elitist; I don’t want them to be,” he said. Not when there is a larger target. “I want them to contribute to conversations about Nigerian literature going as mainstream as Nigerian music and cinema.” ♦

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

Buy Ikenna Okeh’s books. Open Country Mag may earn an affiliate commission from Amazon.

You can also order the books from Rovingheights Bookstore. Open Country Mag may earn an affiliate commission.

More In-depth Stories from Open Country Mag

— Cover Story: Chude Jideonwo‘s Stage of Nigerian Dreams

— In a Time of Fire, Chuma Nwokolo Protects His Purpose

— In Great Grief, Mubanga Kalimamukwento Saw Her Country

— How uHlanga Press Disrupted South African Poetry

— JK Anowe, a Confessional Poet, Confronts Himself

— The Prodigious Arrival of Arinze Ifeakandu

— Aiwanose Odafen‘s Duology of Womanhood

— Momtaza Mehri’s Fluid Diasporas

— The Overlapping Realisms of Eloghosa Osunde

— DK Nnuro Finds His Answers

— How Romeo Oriogun Wrested Poetry from Pain

— Khadija Abdalla Bajaber on Fantasy and the Character of Kenyan Writing