Letlhogonolo Mokgoroane and Alma-Nalisha Cele, the podcasters behind The Cheeky Natives, did not always know what a podcast was. “We would always go to these book events and people would be, like, ‘Oh my gosh, will you guys start a podcast?’” Cele told me on Zoom last November, with Mokgoroane humming in agreement. “And this was early, so we were, like, ‘Podcast? What is that?’ And then we realized, oh my gosh, we’re always talking about books. We love to engage authors. Let’s do this thing where we talk about books ’cause nobody seems to be as interested as we are.”

They come from different backgrounds. Mokgoroane is a lawyer and Cele is a doctor. They, Mokgoroane, grew up without access to books but by age four she, Cele, was already a reader. And yet when the two met, connected by their love of books, they immediately saw the same gap: nobody in the South African literary scene was engaging meaningfully with Black writers in the continent and abroad. And so began The Cheeky Natives in 2017, which now has 67 episodes, each with a different writer, each over an hour long.

The podcast launched with Cele and Mokgoroane discussing the Nigerian novelist Chinelo Okparanta’s Under the Trees. But the catalyst for its current conversational mode—where authors are invited—was another novel they both loved, by a South African: Mohale Mashigo’s The Yearning.

“It really spoke to both of us and we began to have a deeper conversation about what literature means for us,” Mokgoroane recalled. “There were conversations that we’ve had with authors and they were, like, ‘Oh my gosh, I didn’t even think that that was a possible reading of my book.’ There were authors and musicians and artists who have said to us that this is one of the best conversations that they’ve had about their book, because, for us, it’s really about the care, right? We’re invested in the words and what the work can do—not now but like five years from now, 10 years from now. So in many instances it’s also a space for authors to reflect more deeply about their work. I think that that’s what we do at The Cheeky Natives, we make authors think a little more deeply about the work that they put.”

Their guests are selected with intentionality. “So I listened to our first podcast recently and it was just hilarious,” Cele said. “I think we went back to the drawing board. Then we realized that the way we were engaging wasn’t necessarily the way that we wanted to do it. We realized that there’s also a vacuum in critical engagement with the intention of the writing outside of the white gaze, and then we also decided that we’d be really intentional about the kind of writers that we brought onto the podcast, because the personal is political. We think about the kind of politics that they have and whether those are in alignment with what we want to do. I think that’s also being the guide—a sort of mantra.”

In creating this archive, they are also guided by a historical awareness. “I think about Toni Morrison and I think about James Baldwin,” Mokgoroane said. “There are, like, these pieces of interviews that they have and things that you have to sort of fish out, right? And you [find] one here and you piece [two] together. We are hopeful that years from now people can read The Yearning and listen to the conversation and actually have an hour of Mohale Mashigo talking about the journey of writing it and what it means. It would be where you could come if you wanted to listen to authors speak about their work, because I think, even now, there isn’t like an archival system where you can access an abundance of recordings and stuff like that.”

A year before they started The Cheeky Natives, they attended the inaugural Abantu Festival in 2016, the first such event for Black writers in South Africa. Was the intellectual atmosphere of the festival an influence? “I suppose the truth of the matter is, what we are trying to do and what Abantu is trying to do are two different things,” Cele replied. “It’s a festival where people gather for three or four days and celebrate, and all that we were trying to create is an archive.”

Was there a lack then at the festival? “I think it was not a lack but the opportunity that we saw,” Mokgoroane said. “You know, book festivals have panel discussions, so you don’t really have one-on-one discussions. We wanted to offer—to give an author an opportunity to spotlight their work by themselves. Abantu would have existed and ended, but our conversation would still exist even after the festival ends.”

Their backgrounds have shaped their mission. Growing up as a femme boy in Kimberly, a town in Northern Cape, South Africa’s biggest but most impoverished province, Mokgoroane felt like an outcast. It was tough. They lacked access to books, and the early ones they read were by white writers, so the older they grew the more they sought out books by Black writers, and discovered Audre Lorde.

“I remember reading Zami: A New Spelling of My Name and I was just blown away,” they recalled. “That’s how I got into literature. Books were my friends. I was kind of on the periphery and books gave me, you know, the gateway to be able to find new worlds. But books by Black writers came very later on in my life because I then had access to bigger libraries and resources.”

Cele took a different path. Born and raised in Johannesburg, by a reader mother, she was drawn to every available magazine, especially Cosmopolitan, and read them everywhere including at school. “I knew that magazines were in trouble when my mother stopped subscribing,” she recalled. When she began interacting with other readers, she brought that nurturing for books with her.

I ask them about what is lacking in conversations about South African and African literatures. “I think there are perceptions that can be a hindrance,” Cele replied, “particularly around fiction, so there is still a prevailing belief that nonfiction is more serious, that nonfiction sort of holds more weight, and you can see it in the way that people talk about the kind of folks that they buy and consume in this country.”

And then there is the problem of accessibility. “Getting the books out but also getting people to read widely, right? There’s the thing about the cost of books, absolutely exorbitant in this country—it’s ridiculous. What happens to local libraries? What happens to those who don’t have a proper budget and so cannot access books?”

For Mokgoroane, the white gaze is still not being critiqued enough. “When African writers and South African writers are not writing for a particular gaze, the work is not received [elsewhere] in the same way that it can be respected, right? [People sort of act] like the work then it loses its power. What I think is missing is our own people who may be abroad who are supposed to elevate our voices or the writing who don’t necessarily do that. But I also think that the institution of publishing is still lily-white, and so we also need an overhaul of the publishing institution.”

They broke down a sub-issue of book distribution. “There’s still a lot that needs to be done about, like, the conceptual understanding of borders and how borders are preventing, say, Nigerians from reading South Africans. But if a Nigerian is published in the US, we can access their work here, but that’s not to say that Nigerians can access our work in South Africa because, you know, there’s still like a lot of red tape around distribution, publishing, and just the concept of borders that’s preventing us from getting our work in Africa first, and then Africa to the world.”

Still, the vision of The Cheeky Natives is hindered by funding. “There’s a bookstore in D.C. called Busboys and Poets, which is also a restaurant, a venue that’s like absolutely amazing,” Mokgoroane said. “When someone gives us money, we want to build something like that in South Africa, where we have a recording booth in a restaurant, where people can come and listen to live recordings of the podcast, but also live launches of new books. Ultimately, it’s for us to create, later on, an Academy to make books accessible, to create some form of funding where we’re able to give back to local libraries so that everyone, literally everyone who wants to have access to a book, can have access to books.”

Cele sees their archival work as getting African literature its own due. “I think of how we’ve been able to access conversations that James Baldwin had, for example, 20 years ago, how important those kinds of conversations have been in our understanding of his work. And I want to see that being done for writers on the continents. I’m talking, like, books that don’t necessarily have to speak to the extraordinary themes like Critical Race Theory. I want to see what it’s like to have a Black woman talking about a book that speaks to them doing their hair, going about the business of just living. What does it mean to create an archive of Black writers just living? That in 20 years’ time our children can look back and feel. And for me, that really is the prime goal of The Cheeky Natives.” ♦

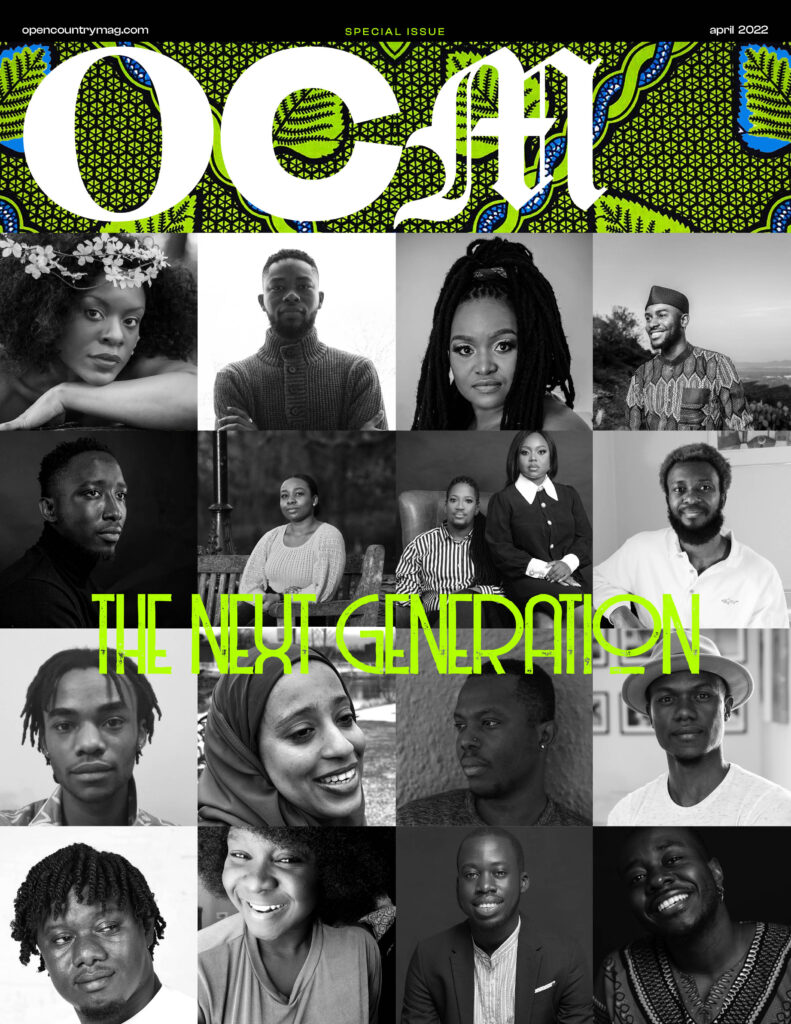

“Inside The Cheeky Natives Podcast, Letlhogonolo Mokgoroane & Alma Nalisha-Cisse’s Archive of Intentionality” appears in The Next Generation special issue of Open Country Mag, profiling 16 writers and curators who have influenced African literary culture in the last five years, curated and edited by Otosirieze Obi-Young.

3 Responses