In Isale Eko, little matters more than survival. It is the world Obalola and his friends, Ifeanyi and Gift, live in and have come to understand well. And for a time, that world is not inescapable. A precocious child, he’s also got a stomach for the ruthlessness of street life. Kazeem, a thug for the Eleniyan, Isale Eko’s foremost gang leader, appreciates his guts. But Nino, who is on his way to becoming the next Eleniyan, sees a different kind of potential. He takes him in as his surrogate son and leads him away from the life he himself has sought to flee.

For Obalola, Nino’s home, across from Kazeem’s daughter, his crush Teni, is a respite from his mother, who is convinced that a regular onslaught of lashes in her religion’s peculiar fashion is the best way to prevent Obalola from meeting a gruesome end like his father, a gang leader murdered in front of his wife and child. Worse happens. Young Obalola’s hope is ripped away when Nino is brutally murdered, and Obalola takes to life on the streets.

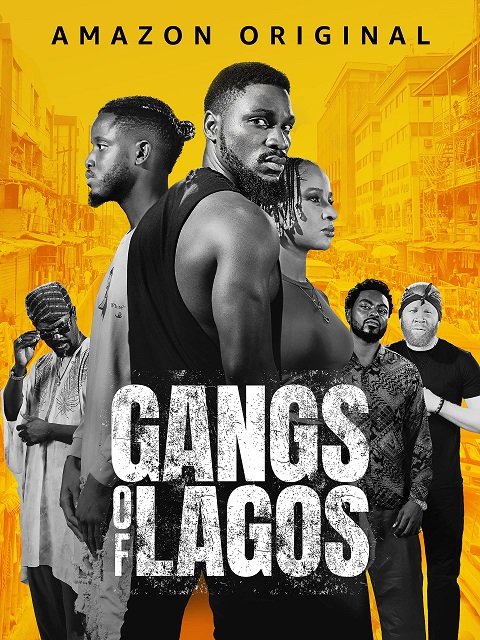

In depicting gang life in bustling Lagos, Jade Osiberu’s Gangs of Lagos, Prime Video’s first Africa Original, tells a story of the hold of legacy and history, and the seeming inevitability of a young man falling into their grasp. Often shot with style, it is framed like an epic.

When next we meet Obalola, he is a young adult, and it is another election season. Kazeem (a wonderfully sinister Olarotimi Fakunle) has risen to Eleniyan in Nino’s place, and Obalola is his trusted muscle. He, Ifeanyi (a naturalistic Chike, the singer), and Gift (Adesua Etomi-Wellington) are in the employ of the former Eleniyan, now a powerful politician running for governor. It promises to be the usual cycle of power, except that a new candidate (Toyin Abraham) is supported by the rival gang. The election brings with it clashes, and Obalola, Ify, and Gift find themselves in the middle of it.

Although we first meet them as children, played by child actors, Obalola, Ifeanyi, and Gift retain chemistry as adults. Even as the times of marching to school and launching into the lagoon at sunset segue into the bleakness of street life, Tobi Bakre, Chike Ezekpeazu, and Adesua Etomi-Wellington achieve an organic friendship that shines through. Shame there isn’t quite enough of it.

The cast turns in solid performances. Tobi Bakre settles comfortably as the older Obalola at war with his fate until a tragedy forces his hand. His is an interesting portrayal of a promising young man who dons the role of a thug well, but only when he has to—like when he roughhouses Kazeem’s nervous debtor, or when he faces off against another gang. Otherwise, he is pensive but resigned, except in the company of Chike’s Ifeanyi, who shines as a hopeful musician, and Etomi-Wellington, a talented actress who here makes do with frustratingly thin material.

Bimbo Ademoye, as an adult Teni newly returned from the US, is a welcome perspective to the film: the daughter of a crime boss sequestered from street life, but not oblivious to her father’s dealings. Fakunle is in his element as Kazeem, whose cruelty is barely masked by his vulpine smile. The two actresses who play mothers bring some ferocity. Chioma Akpotha is seamless as Ifeanyi’s quintessential doting Igbo mother, and then an angry, bereaved woman with that striking monologue (It is more varied acting than her melancholic Africa Movie Academy Award (AMAA) Best Actress winning role in 2007’s Sins of the Flesh). And The Real Housewives of Lagos star Iyabo Ojo is persistent as Obalola’s morally punishing mother.

The fight scenes are an improvement from the typical cartoonish stuff from Nollywood. Some stand out, like Obalola’s in the warehouse, and others, like the final clash, are clunkily choreographed. The street brawls really lean into the macabre, an echo of the violence that pervades Nigeria in reality: the scenes of men hacking into flesh with machetes are familiar enough that they are unsettling to the viewer.

Osiberu is careful not to render Isale Eko in simplistic terms. Crime is potent and people suffer beneath power tussles, but it is also a complex community that turns to the Eleniyan to save their kidnapped children or retrieve stolen bags, a place that prizes family and loyalty. A sure-footed story emerges from this warring dichotomy, but a lot of its themes, of ambition, power, corruption, are crammed into commentary and underwhelming dialogue. These are not aided by poor editing, like how Obalola tells us he has forgotten Nino’s face but, in the very next scene, Nino’s face is there on his room’s wall.

As seen in the friendship at its center, the meanness of Lagos gang life, and the plot-twist betrayal, Gangs of Lagos takes on forceful, compelling ideas, but it feels like we only get a whiff of them. Where it succeeds, above any other recent Nigerian film, is a death scene of a beloved character. It has been so long in Nollywood that a major death meant to elicit powerful emotions actually succeeds in making us feel the hurt of characters. ♦

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

More Film Reviews from Open Country Mag

— Brotherhood, Reviewed: A Policeman and a Robber

— Shanty Town, Reviewed: Crime and Punishment, Fate and Freedom

— A Sunday Affair, Reviewed: A Stumbling Story of Romance and Tested Friendship

— Prophetess, Reviewed: A Modernist Portrayal of Faith

— Blood Sisters, Reviewed: A Rousing Murder Thriller

— La Femme Anjola, Reviewed: An African Neo-Noir Titillates in Crime and Lust

— Swallow, Reviewed: Perturbance in Ordinary Lives

— Ife, Reviewed: Lesbian Love in Bourgie Lagos

— Nne, Reviewed: Two Mothers and a Son

— The Men’s Club, Reviewed: A Charming Depiction of Male Friendship