Compiled by Emmanuel Esomnofu and Paula Willie-Okafor.

Every month should be Women’s History Month, but here at Open Country Mag, we are closing the designated month of March 2022 by highlighting 22 writers born before the last 60 years. They broke grounds and they were female. They are all gone and many of them are still underread. Some are much better known than others but most are almost forgotten outside their countries. The majority were strictly literary writers and thinkers. A few entered advocacy and even held political offices. And despite the limitations in their times and lives, they produced influential work. (Besides, so much is made of deceased great white male writers; it’s time for deceased great African female writers.)

Our list is ordered by birth, so the last named writer, drifting a bit, was born 58 years ago.

________

Mabel Dove Danquah (1905 – 1984)

Mabel Dove Danquah was a pioneer of modern literary writing in West Africa. Her work was considered a precursor to feminism in the region. She was born in Accra, Ghana, and later lived in Sierra Leone and England.

Danquah was an important journalist, writing for Ghana’s first daily newspaper The Times of West Africa, where the column “Ladies’ Corner” made her popular. She’d write for other newspapers, too, and in 1951 became editor of the Accra Evening News, only the second woman to ever hold the position.

Before going blind in 1972, Danquah published several books including The Happenings of the Night (1931), The Adventures of the Black Girl in Her Search for Mr Shaw (1934), Anticipation (1947), The Torn Veil (1947), Payment (1947), Invisible Scar (1966), and Evidence of Passion (1969).

________

Noni Jabavu (1919 – 2008)

She was born Helen Nontando Jabavu in 1919, in Middledrift, South Africa, to a family of Bantu Christians. Her father, like many of the opportuned in African countries then under colonial rule, studied in Britain and returned home to South Africa. She attended The Mount School in York and the Royal Academy of Music in London. But unlike her father, she stayed back in England. She married and had a daughter with an RAF man who died in World War II. She later remarried, this time a wealthy Englishman.

In 1960, Jabavu published her first book and memoir, Drawn in Colour: African Contrasts. In its first year, it was reprinted five times. It was a remarkable feat considering that she was the first Black South African woman to publish a memoir and to publish a book in the UK. In 1963, she published The Ochre People: Scenes from a South African Life, a sequel and travelogue.

For eight months, beginning in 1961, Jabavu was editor of The New Strand (which was, until that year, The Strand) in London. When she took up the role, a lot of people were surprised, because not only was she a Black woman, she was South African-born. “Miss Jabavu has led such a varied life that she will bring a completely fresh outlook to the magazine,” said Ernest Kay, one of the proprietors of The New Strand. “She couldn’t be conventional if she tried.”

In the late ‘70s, Jabavu returned to South Africa to research a biography of her father. It was around this time that she began writing a weekly column for Daily Dispatch. The column was titled “Noni on Wednesdays.”

Despite her relative success, her books were unavailable to a lot of South Africans and are now out of print in the UK and the US. Ironically, in 2005, three years before her death, South Africa’s Ministry of Arts and Culture honoured her with a lifetime achievement award.

In 2020, her Daily Dispatch columns were collected in Noni Jabavu: A Stranger at Home, with an introduction by Makhosazana Xaba and Athambile Masola.

________

Elsa Joubert (1922 – 2020)

Joubert was born in Western Cape, South Africa. At 23, she graduated from the University of Cape Town with an MA in Dutch-Afrikaans literature.

A writer of travelogue, fiction, and autobiography, Joubert enjoyed a prolific career. She got her big break with Die Swerfjare van Poppie Nongena (originally published in 1978 but republished two years later in English as The Long Journey of Poppie Nongena). The novel spoke to the racial tension in South Africa.

Admirers of her work include Andre Brink and J. M. Coetzee, who commented on her 2019 autobiography Cul-de-sac: “Seldom have the humiliations of old age been so nakedly open.”

She passed on amidst the coronavirus pandemic, under lockdown in a care home in Cape Town. She was 97.

________

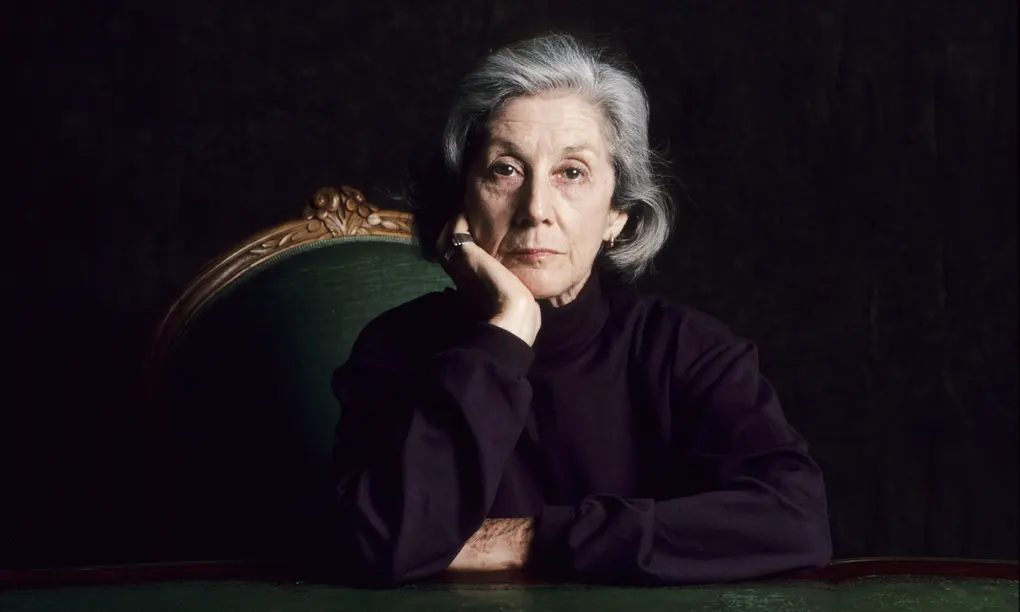

Nadine Gordimer (1923 – 2014)

Regarded as one of the most important writers of the 20th century, Nadine Gordimer wrote profoundly about the intersecting realities of people in her native South Africa. She was especially a vocal critic of Apartheid, as well as an activist. The South African government banned several of her books, often for long periods.

Her best-known works include Occasion for Loving (1963); A Guest of Honor (1972), for which she received the James Tait Black Memorial Prize; The Conservationist (1974), for which she won the Booker Prize; Burger’s Daughter (1979); July’s People (1981); and The Pickup (2002).

She won the 1991 Nobel Prize in Literature for writing with “intense immediacy about the extremely complicated personal and social relationships in her environment.”

________

Efua Sutherland (1924 – 1996)

Efua Sutherland was born in 1924, in Cape Coast, present-day Ghana. After attending St. Monica’s School and Training College, Mampong, she left to further her studies in England. She earned a BA from Homerton College, Cambridge, one of the first African women to attend the university, and continued at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London.

At 27, she returned to Accra where she became a teacher at Fijai Secondary School, Sekondi, and afterwards her alma mater, St. Monica’s, until 1954. After Ghana’s independence, she organized the Ghana Society of Writers in 1957, helped start the literary magazine Okyeame, and founded Ghana Experimental Players and Ghana Drama Studio in 1961.

The studio, now the Writers’ Workshop in the Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana, produced a number of her plays, including Foriwa (1962), Edufa (1967), and The Marriage of Anansewa: A Storytelling Drama (1975). Some of her children’s books are The Roadmakers (1961), Playtime in Africa (1962), Vulture! Vulture! (1968), and Tahinta (1968). Her collection of Ghanaian folklore and fairytales, The Voice in the Forest, was published in 1983.

Sutherland died aged 71. Margaret Busby wrote afterwards: “She held a special place [in the life of her country] having been the dominant presence in theater there for more than three decades.”

________

Orlanda Amarílis (1924 – 2014)

Orlanda Amarílis was born in Assomada, Santa Catarina, Cape Verde, to a literary family that includes Baltazar Lopes da Silva and her father, Armando Napoleão Rodrigues Fernandes, who published the first Cape Verdean Creole dictionary. She further married the Portuguese-Cape Verdean writer Manuel Ferreira.

After her secondary education, Amarílis moved to Goa, and there she completed her primary teacher training. She became a member of the Portuguese Movement Against Apartheid (Movimento Português Contra o Apartheid), the Portuguese Movement for Peace (Movimento Português para a Paz), and the Portuguese Association of Writers (Associação Portuguesa de Escritores).

Amarílis fiction examined the Cape Verdean diaspora and the lives and experiences of Cape Verdean women. She began her writing career in 1944 at the Cape Verdean magazine Certeza. Her short story collections include Cais-do-Sodré té Salamansa (1974), Ilhéu dos Pássaros (1983), and A Casa dos Mastros (1989). Her children’s books are Folha a folha (1987) and A Tartaruguinha [The Little Turtle] (1997).

Her short stories have been included in the anthologies Across the Atlantic: An Anthology of Cape Verdean Literature (1986) and A New Reader’s Guide to African Literature (1983), in the magazines COLÓQUIO / Letras, África, and Loreto 13, and have been translated into several languages.

________

Myriam Ben (1928 – 2001)

She was born Marylise Ben Haim in Algiers, Algeria, to a communist father and an Andalusian Jewish mother.

Her artistic career spans poetry, fiction, and painting. She published collections of short stories and poetry from the late ‘60s, but the 1986 novel Sabrina was her longest and most acclaimed work. It follows two Muslim lovers raised in French culture and finding it hard to adapt to the conservative Algerian government. The novel explores the cultural differences of both worlds, and the nuances in-between.

Ben advocated for the “indigenous poor,” using her teaching and writing to inspire people to be politically conscious and to embrace a decolonized sense of history.

________

Mariam Ba (1929 – 1981)

Mariam Ba was born in Dakar, Senegal, during French colonial rule. Her father was a government official, and she received quality Eurocentric education, and became a published essayist before she finished her secondary education, and a teacher in 1947. But she left her job when her health was at risk due to the stress of raising her large family. Later, she divorced her husband, a Senegalese politician, and worked as a school inspector and secretary.

Before becoming a fiction writer, Ba was involved in women’s advocacy. A member of various women’s organizations and a prominent essayist and lecturer, she addressed subjects ranging from education and marriage to female genital mutilation. “We do not have time to waste if we are going to bring something better to African women,” she wrote in The Feminist Companion to Literature in English (1990).

Her two acclaimed novels, published in her later years, were largely influenced by her own experiences. She was 51 years old when Une si longue lettre (So Long a Letter) came out in 1980. Scarlet Song was published in 1981. Both depict women subjected to polygamy. Like many African writers at the time, she explored the way societies grappled with their traditional cultures and colonial influences.

________

Grace Ogot (1930 – 2015)

Grace Ogot’s work examined traditional Luo life and the negotiation between traditional and Western cultures in modern Kenya.

After attending the Nursing Training Hospital in Uganda up to 1953, Ogot worked at St. Thomas Hospital for Mothers and Babies in London and at Maseno Hospital in Kenya, as a midwifery tutor and nursing sister. She also worked as a scriptwriter and announcer for the BBC and as a columnist for the East African Standard.

Ogot’s experience as a nurse informed much of her fiction, with several works addressing the conflict between traditional and Western medicine. She was the first woman to be published by the East African Publishing House. Her novel The Promised Land (1966) tells of Luo pioneers in Tanzania and Kenya. Her stories were featured in Black Orpheus and Transition, and in collections such as Land Without Thunder (1968), The Other Woman (1976), and The Island of Tears (1980).

Ogot held a ministerial position in Kenya’s government, and was a member of the National Assembly from 1983 to 1992. She was Assistant Minister of Culture and Social Services under President Daniel Moi—the only woman to hold a cabinet-level post at the time.

Three of her novels were published posthumously by her husband, all in 2018: Simbi Nyaima: The Lake that Sank, The Royal Bead, and Princess Nyilaak.

________

Alda Lara (1930 – 1962)

Alda Lara was born into a wealthy family in Angola. After attending a women’s school in Sá da Bandeira, she left for Portugal to complete her secondary education, and subsequently enrolled in Lisbon University, where she began her literary career, publishing poetry in Mensagem, a journal for Africans.

Later, she earned a degree in medicine from the University of Coimbra, and wrote for newspapers and magazines, including the Jornal de Benguela, the Jornal de Angola, and the ABC e Ciência.

An essayist, doctor, poet, and activist, her work reflects political and social consciousness, with a focus on identity, freedom, justice, motherhood and womanhood, resistance against colonial rule, and national liberation. Her poems appeared in more publications: Antologia de Poesias Angolanas (1958), A Mostrsa de Poesia in Estudos Ultramarinos (1959), and Anthologia da Terra Portuguesa (1960/61).

Lara returned to Angola in 1961, after 13 years in Portugal. She died shortly after, in 1962, aged 32. Her collected works—Poemas (1966), Tempo de Chuva (1973), Poesia (1979) and Poemas (1984)—were published by her husband posthumously.

In her honour, the city of Lubango established the Prémio Alda Lara (the Alda Lara Prize for Poetry).

________

Alifa Rifaat (1930 – 1996)

Alifa Rifaat’s writing was often controversial in Egypt. She mostly wrote short stories, rich and complex in their depictions of everyday society. The dynamics of female sexuality was also a favored theme of hers, contrasting delicately with the otherwise religious practices of the larger Egyptian society.

Prior to the 1980s, her work was largely focused on Arabic romances, not infusing the social awareness she would later be known for, until she met the translator Denys John-Davies, who also influenced her to tell stories in more colloquial Arabic.

Rifaat’s most popular work is Distant View of a Minaret and Other Stories, translated into English in 1983. Later works include On a Long Winter’s Night (1980) and The Pharaoh’s Jewel (1991), a historical novel.

________

Flora Nwapa (1931 – 1993)

The first African female novelist to be published in the English language in Britain, Flora Nwapa has been called “the mother of modern African literature.” She was born in Oguta, Nigeria, the eldest of six children. After earning a degree at the University College, Ibadan, in 1957, she went to Edinburgh University, Scotland, for a diploma in Education in 1958. On returning to Nigeria, Nwapa worked in education and civil service, and served in cabinet positions.

Her first novel, Efuru, was published in 1966. She’d sent the manuscript to Chinua Achebe in 1962, who replied positively and included money to mail the manuscript to Heinemann in London.

Nwapa’s other works include the novels Idu (1970), Never Again (1975), One Is Enough (1981), and Women are Different (1986); two collections of stories, This Is Lagos (1971) and Wives at War (1980); and a poetry collection, Cassava Song and Rice Song (1986). She authored children’s books and her work appeared in magazines and anthologies, including Présence Africaine, Black Orpheus, and Daughters of Africa. Her last novel, The Lake Goddess, was published posthumously.

One of the first African female publishers, she founded Tana Press in 1977, where she published her own work as well as work from other writers. Although she initially declined to be labeled “feminist,” her work elevated women. She died aged 62.

________

Nawal El Saadawi (1931 – 2021)

Nawal El Saadawi was the second of nine children, born in a small village outside Cairo. Even as a child, she spoke out against the male-dominated society in which she lived, resisting when her family attempted to marry her off at the age of 10.

In 1972, she garnered prominence for her book Women and Sex, which addressed sexual oppression and the violence perpetrated against women’s bodies, and for which she was dismissed from her job in the Ministry of Health. Her most renowned novel, Woman at Point Zero, was published in 1975. It is told by Firdaus, a woman who shares her life story before her execution for murder, and is based on El Saadawi’s encounter of a female prisoner.

El Saadawi faced criticism, censorship, and death threats. In 1981, she was briefly imprisoned by President Anwar Sadat and released a month later, after his assassination. Alhough she was denied pen and paper in prison, she continued to write using a smuggled eyebrow pencil and toilet paper. After her life was threatened by religious extremists in 1993, she fled to the US where she became a writer-in-residence at the Asian and African Languages Department at Duke University. She returned to Egypt in 1996.

El Saadawi ran for president in 2005, ceasing her campaign after she said she was prevented by security forces from holding rallies, and in 2011, joined the mass protests that resulted in Hosni Mubarak’s removal. In 2020, TIME put her on one of their 100 Women of the Year covers, for the year 1981. In 2004, she received the North-South Prize from the Council of Europe, and was awarded the Inana International Prize in Belgium in 2005.

She published more than 50 books, including The Circling Song (1989), The Fall of the Imam (1988), The Innocence of the Devil (1994), Breaking Down (2004), and Notebook for 85 Year Old Woman (2017).

“Danger has been a part of my life ever since I picked up a pen and wrote,” she wrote after her release from prison. “Nothing is more perilous than truth in a world that lies.”

She died aged 89.

________

Miriam Tlali (1933 – 2017)

Tlali is renowned as the first black woman in South Africa to publish a novel in English. That book, Between Two Worlds, appeared in 1975, when she was 42. Her work confronted the Apartheid government, and was frequently banned.

A practical idealist, Tlali took up publishing and curating work that protested Apartheid and its relative social problems. The 1976 Soweto Uprising formed the backdrop of her second novel Amandla (1980). Her 1984 book Mihloti was an amalgam of stories, interviews, and non-fiction, published by Skotaville, which she co-founded.

She also co-founded and contributed to Staffrider magazine, writing a column titled “Soweto Speaking,” where she discussed and dissected varying strata of the Soweto experience.

________

Delphine Zanga Tsogo (1935 – 2020)

Delphine Zanga Tsogo was a Cameroonian writer and feminist. She was educated at Douala and would go on to study nursing in France.

Her first book, Vies de Femmes (Women’s Lives), appeared in 1983, followed by 1984’s L’Oiseau en cage (The Caged Bird). Both books explore the private and public lives of Cameroonian women.

Tsogo was also involved in her country’s politics. She was elected national president of the Council of Cameroonian Women in 1964 and served in the National Assembly from 1965 to 1972. She was also Minister for Social Affairs from 1975 to 1984.

________

Zulu Sofola (1935 – 1995)

Zulu Sofola (full name: Nwazuluwa Onuekwuke Sofola) is regarded as the first published Nigerian female playwright and the first female Professor of Theatre Arts in Africa. After completing her secondary education in the US, she earned a BA in English from Virginia Union University, Richmond, and an MA in Drama (Playwriting and Production) from the Catholic University of America, Washington. She returned to Nigeria where she became a lecturer at the University of Ibadan and completed her PhD in Theatre Arts (Tragic Theory). She won a Fulbright Scholarship.

An acclaimed dramatist and director, Sofola published several plays. Her work took aim at societal ills, ranging from misogyny to political injustice from military rule, and championed social justice and fair and equal treatment. Her plays include The Deer and The Hunters Pearl (1969), Eclipso and the Fantasia (1990), Wedlock of the Gods (1973), King Emene (1974), Memories in the Moonlight (1986), Old Wines Are Tasty (1973), The Operators (1973), The Showers (1991) and The Wizard of the Law (1975).

Sofola represented Nigeria at the first International Women Playwrights Conference, and, in 2002, had the National Prize for Creative Writing named after her. She died aged 60.

________

Molara Ogundipe (1940 – 2019)

Abiodun Omolara Ogundipe was born in Lagos, later attending the Queen’s School, Ede. She was the first woman to graduate with first-class honours in English at University College, Ibadan. She lectured in diverse fields relating to language and gender, infusing cultural perspectives in her teachings, and later her writing.

Most of Ogundipe’s work was done in academia and general writing. A notable book of hers is Re-creating Ourselves: African Women & Critical Transformations (1994). Her work appears in the 1984 anthology Sisterhood Is Global: The International Women’s Movement Anthology, edited by Robin Morgan.

She published a poetry book, Sew the Old Days and Other Poems (1985). Her poems appear in the 1992 anthology Daughters of Africa, edited by Margaret Busby.

________

Buchi Emecheta (1944 – 2017)

Buchi Emecheta was born in Lagos, Nigeria. She spent her early childhood at an all-girls’ missionary school, and, after her father died, received a full scholarship to Methodist Girls’ School in Yaba. During this time, her mother also died, and in 1960, at the age of 16, she married Sylvester Onwordi, to whom she had been engaged since she was 11 years old.

Emecheta joined her husband in London, but her marriage was unhappy and her husband abusive, and she left him, pregnant with their fifth child. She worked to support her children alone while she earned a degree in Sociology from the University of London, where she also became a Fellow in 1986 and got her PhD in 1991.

She wrote about her experiences as a Black British woman in a regular column in the New Statesman, and published her first book, In the Ditch, as a collection of these pieces in 1972. Her fiction explored motherhood, sexual discrimination, female independence, child slavery, freedom through education, and the conflict between tradition and modernization. She was the author of more than 20 books, including the novels The Bride Price (1976), The Joys of Motherhood (1979), The Slave Girl (1977), Second Class Citizen (1974), and Destination Biafra (1982), as well as the children’s books Titch the Cat (1979) and Nowhere To Play (1980).

From 1965 to 1978, she worked as a library officer for the British Museum, a youth worker and sociologist for the Inner London Education Authority, and as a community worker.

She once described her fiction as “stories of the world, where women face the universal problems of poverty and oppression, and the longer they stay, no matter where they have come from originally, the more the problems become identical.”

In 2005, she was made an OBE for services to literature. She died aged 72.

________

Angele Rawiri (1954 – 2010)

Angele Rawiri is noted as the first novelist from Gabon. She was born in Port-Gentil. Her father was a poet and the president of the Gabonese Senate at the time, and her mother was a teacher. Despite her father’s status, her life was not in the limelight. She attended the Lycée of Alès in France and earned a baccalaureate at the Girls’ College at Vanves, and another at the Institut Lentonnet in Paris. She lived in London for two years, supporting herself by modelling for magazines and appearing in small film roles.

In 1979, Rawiri returned to Gabon, where she worked as a translator and interpreter of English for a state oil company. Her brother encouraged her to write her first two novels, Elonga (1986) and G’amerakano (1983), and later she published her third and final novel Fureurs et cris de femmes (Fury and Cries of Women) in 1989. Although they have little in common, her three published novels are often referred to as a “trilogy.”

“I hadn’t thought about [becoming Gabon’s first novelist],” she said in a 1988 interview. “I was rather taken up by my reflections, my doubts, my worries, my fears. When the novel came out, I found out that I was the first.”

She died while working on her fourth novel in Paris.

________

Margaret Ogola (1958 – 2011)

Margaret Atieno Ogola was a pediatrician, which influenced her centering of Kenyan women and society in her writing.

Her debut novel The River and the Source (1994) brought to readers the story of four generations of Kenyan women. It won the 1995 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best First Book, Africa Region. Its sequel, I Swear by Apollo (2002), was followed by 2005’s Place of Destiny, a story of a woman dying of cancer.

Around this time, Ogola had been diagnosed of cancer herself, but she continued supporting literary and communal work until her death at age 53.

________

Zindzi Mandela (1960 – 2020)

Zindziswa “Zindzi” Mandela was three years old when her father, former South African President Nelson Mandela, was sentenced to life imprisonment. Later, her mother, Winnie Mandela, was also sent to prison for her continued stand against Apartheid. Zindzi, the third and youngest of their daughters, was only 12 when she wrote to the United Nations, requesting a pardon from the South African authorities for her parents.

She attended the Waterford KaMhlaba United World College of Southern Africa in Swaziland, and earned a law degree from the University of Cape Town in 1985.

Zindzi’s poetry was featured in the anthology Black As I Am (1978). Her work has also been published in Somehow We Survive: An Anthology of South African Writing and in Daughters of Africa.

She was an anti-Apartheid activist alongside her parents, and became her father’s representative; in his stead, she read his refusal letter to the conditional release offered him in 1985. She also served as stand-in First Lady of South Africa between 1996 and 1998, when her father was unmarried. She was appointed South Africa’s ambassador to Denmark in 2014, and served in the role until her passing in 2020, at the age of 59. She was due to be named the country’s ambassador to Liberia.

________

Yvonne Vera (1964 – 2005)

Born in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, then Southern Rhodesia, Yvonne Vera’s parents were both teachers. After attending Mzilikazi High School, she too became a teacher of English Literature at Njube High School. She left for Canada where she married John Jose, who had also taught at Njube. There, she completed an undergraduate and master’s degree, a PhD, and taught literature at York University, Toronto.

She was still a student when her first book, Why Don’t You Carve Other Animals, a collection of short stories, was published in 1992. It was followed by the novels Nehanda (1993) and Without a Name (1994).

In 1995, she returned to Zimbabwe where she became director of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe from 1997 to 2003. During this time, she published three more novels: Under the Tongue (1996), awarded the Commonwealth Writer’s Prize for Best Novel, Africa Region; Butterfly Burning (1998); and The Stone Virgins (2002), which won the Macmillan Writer’s Prize for Africa.

Vera’s work interrogates gender inequality in Zimbabwe before and after the country’s struggle for independence. It is distinct for its lyricism and boldness in tackling abortion, rape, infanticide, and incest. In 2004, she received the Swedish PEN Tucholsky Prize “for a corpus of works dealing with taboo subjects.”

Vera was working on her would-be sixth novel, Obedience, when she passed from meningitis at the age of 40. It was never published.

“Fearless and courageous are two adjectives that sum up Vera’s personality and her writing,” Helon Habila wrote after her death.

Vera once said, “I would love to be remembered as a writer who had no fear for words and who had an intense love for her nation.”

________

Neshani Andreas (1964 – 2011)

Neshani Andreas began her literary career at a time when writing was an activity disregarded in Namibia. She had been writing since her childhood, but her passion lived in secrecy for the longest time; she was in her early twenties when she told her friends, and despite the negative response, she continued to write.

Andreas was born to fish factory workers, the second of eight children. She attended the Ongwediva Teachers’ College, and taught English, history, and business economics from 1988 to 1992. She earned a BA and a diploma in Education at the University of Namibia, Windhoek, a new institution at the time. She was Associate Peace Corps Director of the US Peace Corps in Namibia for four years, subsequently working for the Forum of African Women Educationalists in Namibia (FAWENA).

Her writing career took off after meeting a fellow Peace Corps volunteer who acknowledged her dreams—something she had never experienced before. It spurred her to complete the manuscript of her debut novel in 1999. The Purple Violet of Oshaantu, published in 2001, explores the lives of women in traditional Namibian society, inspired by her own living and teaching in rural areas. It was the first and only book by a Namibian writer to be included in the Heinemann African Writers Series.

In 2010, Andreas was diagnosed with lung cancer. She died in 2011, at the age of 46.

Miriam Tlali. Photograph by Fairlady/Brett Eloff.

Mabel Dove Danquah by Felicia Abban, c. 1955. Digitized unedited photograph by Laurian R. Bowles.

Elsa Joubert. From The Johannesburg Review of Books.

Yvonne Vera. From Prabook.

Delphine Zanga Tsogo. From Memoires de Guerre.

Zindzi Mandela. From CNN.

Zulu Sofola.

Neshani Andreas. From The Wonyingi Blog.

Paris january 25. File photo: Nadine Gordimer poses during promotion. Photo by Ulf Andersen / Getty Images

Orlanda Amarilis. Photo by Orlanda Amarílis, dated summer 1993, taken in Vales, Algarve. from brito-semedo.blogs.sapo.pt.

Molara Ogundipe. From thenationonlineeng.net.

Mariama Ba. From Blackpast.org.

Efua Sutherland. From Maakola.

Grace Ogot. From standardmedia.co.ke.

Flora Nwapa. From Guardian NG.

Angele Rawiri. From Jifa Book Club.

Buchi Emecheta. From BBC.

Margaret Ogola. From Wikipedia.

Aminatta Sophie Dieye.

Alda Lara. From Descendencias Magazine.

Nawal El Saadawi. Photo: David Degner/Getty Images. From the Guardian.

3 Responses

I enjoyed learning about these literary icons.

Thanks for documenting their legacy.

I am inspired.