Suyi Davies Okungbowa took an unusual path to publication, which is why he sees his career as something he “kind of stumbled upon.” He had been writing and getting paid for his work—mostly journalistic articles—but made his first sale of a short story in 2015, to the now defunct science fiction and fantasy (SFF) magazine Mothership Zeta. The sale opened his eyes to what he could do, and get, for his writing. So he started putting out more short fiction and sending them out to SFF markets in North America.

At the time he was in Lagos, working for a multinational accounting firm on The Island, and making the commute every weekday from where he lived in Gbagada, on The Mainland. His move to Lagos, from Benin City where he grew up, gave him the space and time to write his debut novel, David Mogo, Godhunter. The manuscript began as a fun project, an attempt to avoid Lagos’ infamous traffic by staying a few more extra hours at work. The eponymous character David Mogo’s journey mirrored Okungbowa’s then: a normal guy just working to make some money and keep a roof over his head.

When Abaddon Books, an imprint at Rebellion Publishing, made an open call for submissions, he sent off a part of the manuscript on a whim, and during that time, went on a scholarship to the Milford SF Writers’ Workshop in the UK, where meeting writers from different backgrounds led him to want to take writing seriously and professionally. He joined an online forum, Codex Writers’ Group, where he learned about markets and publishing trends, giving and receiving critiques.

By the time an offer of publication came from Rebellion Publishing in 2019, he was already working on a second novel manuscript, which became Son of the Storm, the first in his Nameless Republic series. Rebellion made an offer for the second manuscript, and it was only then that he queried a literary agent who began to represent him, shopping Son of the Storm to more publishers. It was an unusual turn of events, as African authors looking to traditionally publish in North America and the UK have to get an agent first. Then came “a stroke of luck.” An editor at Orbit, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, had read one of his stories in Apex Magazine. The editor bought the manuscript.

He was at his MFA programme at the University of Arizona when David Mogo, Godhunter came out, and before he graduated, Son of the Storm was released, too. He was leaving with two books on his belt, and a teaching offer from the University of Ottawa saw him move to Canada.

“Because of where we come from, because of the resources available to Nigerians living on the continent, short stories are one of the easier mediums to use to break into the market,” Okungbowa told me on a Zoom call in late December. “Longer works—very difficult. Not because editors don’t want them or because we’re not submitting, but because the conditions under which we work, as Nigerians living on the continent, make it difficult to sustain long works. If you talk about Internet, time, power, having a laptop—these are all things that are barriers to entry. It’s no surprise my productivity skyrocketed once I wasn’t shackled by those constraints and challenges. Though there are people who can work in spite of the barriers, but they have to invest more in doing so. When people think about work produced, developed, created on the continent, they often think that it’s about the story itself and how it’s received, but it’s about the creation and the time to do so. You’re not going to spend four hours in Lagos traffic and then go home to write—it just doesn’t work like that. Having access to resources sort of gives me the privilege to create even more. Part of why I do what I do now is because it’s a gift in a way, and I can’t waste it.”

Having written while living in Nigeria and outside Nigeria, he tries to find a balance. He’s always thinking about who he’s talking to, whose emotions he’s trying to tap into—who he’s loving when he writes. A balance is required in opening up and at the same time protecting the work and demonstrating how it needs to be present. And that difference exists when writing from different spaces, because when writing on the continent, there is the pressure to not “educate,” but in writing from other spaces and surrounded by other people of varying backgrounds, there arises value in “educating” your reader.

It took a lot for him to get his feet in the door. “Things had to come together at different points for each stage to progress,” he says.

Writing fantasy, for Okungbowa, isn’t just about wars or empires but about how people function within systems. He uses the term “Storytelling Engine” to ask questions of his work: What are the things powering the story? Setting? Character? Inequality? Preservation? “What am I leaning on?” he breaks it down. “What am I going to as my default? How the character answers the question becomes a function of the society they’re part of.”

It guides how he views his Nameless Republic series. “The first book, you introduce the world; second book, you break the world; and then the third book, you maybe fix it, or fashion a new world out of the one you broke.”

The world of Son of the Storm places intrinsic value on skin colour. He came up with a new value system, one the people of Oon hold in high regard: the land, the dark humus of the soil where wealth lies and which serves as food. The closer the colour of the skin is to the colour of the soil, the more favoured one is by the gods. By combining geography with spirituality, Bassa, a country in this world, turned this into a caste system.

Colourism in Africa is something he wishes more writers talked about as they did racism, and with Son of the Storm, he wanted that to be front and centre. Bassa may do this overtly, but for African and Black societies, it is often covert.

His method is to try and understand the society the character is in, and if he doesn’t, he would know that the character does not answer the question sufficiently. He says he goes beyond trying to make his characters different. He asks what purpose they serve; what are they trying to do in the story. What questions are they attempting to address? If the answers to his questions are not satisfactory or he doesn’t have a well to draw on, he lets the story go, sticks to what he knows.

Writing David Mogo taught him to ask questions about unconscious character choices. His character Femi, the director of LASPAC (Lagos State Paranormal Commission), was originally a man, because this was the norm in government agencies in Nigeria. With Son of the Storm, he wanted to upend things that would come “naturally” in the way he thinks about the world. Which is why Danso’s persona and profession are a far cry from David Mogo’s. Danso’s conceptualisation began with him saying to himself, “I want a hero who cannot fight. One that doesn’t know how to use a sword, and he’s also not comic relief. He’s useful, but useful in a way that’s different from the typical fantasy hero.” His aim is to show a spectrum of Black masculinity.

“One of the mistakes many authors make,” he says, “is that they try to make a list of things they want to tick off and say, ‘I have correctly represented this character.’ That is the problem because there’s no such thing. No one is ever going to say, okay, now that you’ve done this list of things, you have correctly represented Black people in your stories.”

He studies bad tropes more than he does good tropes. “I remember saying if I have queer people in my books, they’re not going to die, because their death is a common trope.” He mentions the Bechdel Test. “The one way to solve that is to just have more women in your story.”

The contemporary Nigerian reality and struggle is something Okungbowa strives to represent. While drafting Warrior of the Wind, the second novel in the Nameless Republic series, he wrote a futuristic climate story partly inspired by the Otodo Gbame demolition and the violent eviction of residents from their fishing community. He was in Lagos during the EndSARS protests. He believes the protests need to have a place in Nigerian literature, and is looking forward to doing that with his writing.

But there are compromises as a Nigerian writer writing Nigerian characters, because some tropes, writing choices, and expectations of a genre do not easily translate into a space outside of where these concepts were designed. Example: car chases on a Nigerian road.

Okungbowa wishes more people asked him the fun stuff he does that isn’t writing. Like football. Like his height. Or his playlists for his books. Or the Mike Bamidele movies that scared him as a child, like that film Evil Dead. He believes he’d be pals with Lilong from Son of the Storm, that the two of them would “shade everybody,” and that he would beat up Danso in a fight. (Anyone could).

I ask him how it feels to be where he is now and he jokes that he is “catching up.” His aim, he says, has never been to be a Massive Big-Name Writer. What he wants is to produce a lot more work. He wants to tell stories in whatever form—comics, TV, film—and wants to have a presence in spaces, from translation to appearances and speaking. He also wants to put himself out there as an academic, as both scholar and artist.

Outside his own writing, he wants to start working on a structured way to send the ladder down. He is talking to people about ways to start pipelines for writers living in the continent, about how opportunities can be created. When he talks about his bursary to the Milford Workshop, he explains that the scholarship did not cover visa costs and airfare, that he had to figure out the logistics himself. He talks about being lucky to get a visa—because African writers have been known to be denied visas, despite their legitimate reasons for travel.

In his words, how he got this far is “luck and opportunity meeting some form of preparation.” Yet it was somewhat in his control: write, submit, repeat. Show up and hope that it pays off. ♦

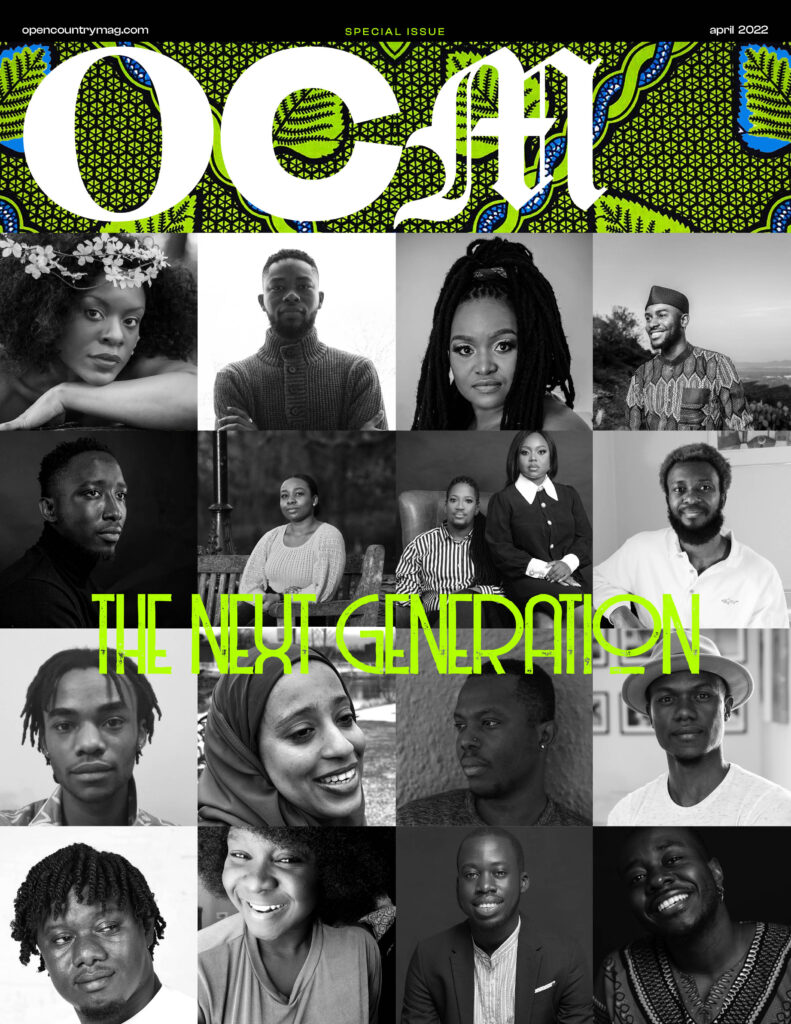

“Suyi Davies Okungbowa Knows What It Takes” appears in The Next Generation special issue of Open Country Mag, profiling 16 writers and curators who have influenced African literary culture in the last five years, curated and edited by Otosirieze Obi-Young.

4 Responses