Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki did not enter the literary scene with a bang, but with a series of little moments that would accumulate to notability. He had been trying, unsuccessfully, to sell a story for three years, and all he heard was silence from editors. Then in 2018, Cosmic Roots and Eldritch Shores acquired his short story “The Witching Hour.” The following year, the story won him the Nommo Award for Best Speculative Short Story by an African.

His journey has since seen his work recognized by the Nebula Awards, the Locus Awards, the British Science Fiction Association Awards, and the Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award. But while Ekpeki is a fantastic writer himself, it is his work as a curator that has achieved major impact in the African literary scene.

In 2019, he sent a short story, “Ife-Iyoku, the Tale of Imadeyunuagbon”—which would later be expanded into the Nebula-nominated and Otherwise Award-winning novella—to Aurelia Leo, a small press founded by the American editor Zelda Knight. Partly inspired by Ekpeki’s story, Knight offered to collaborate with him on an anthology of stories by speculative fiction by writers of African descent. The agreement led to a year of editorial and creative labor complicated by health challenges, a fire hazard, financial constraints, and mental fatigue. Their efforts culminated in Dominion: An Anthology of Speculative Fiction from Africa and the African Diaspora, featuring writers from Nigeria, Uganda, Australia, Tanzania, the United States, and Senegal, among other countries.

Dominion won the 2021 British Fantasy Award for Best Anthology and was a finalist for the 2021 Locus Award for Best Anthology. Cosmic Roots and Eldritch Shores called it “a worthwhile read,” the British Fantasy Society deemed it a “gripping and thought-provoking” collection, and Vector, the journal of the British Science Fiction Association, praising its “startling range of genres that provides something for everyone.” The American film historian and academic Tananarive Due wrote: “I’ve never read an anthology like it.”

For an anthology curated by an African, the success was unprecedented. Then came a book deal with Todotcom Publishing, arguably the biggest publisher in the speculative fiction market.

“A lot of people were pleasantly perplexed,” Ekpeki says of the initial reaction. “Almost every review had a phrase like ‘this is unusual speculative fiction based on unusual cultures,’ so they still find African speculative fiction unusual. There is still a lot of ground for us to cover, it would seem.”

One might think that the commercial and critical triumphs of books like Tomi Adeyemi’s Children of Blood and Bone, Akwaeke Emezi’s Freshwater, and Nnedi Okorafor’s Who Fears Death signal a breakthrough for African writers in speculative fiction, but Ekpeki is not convinced at all.

“That success is not trickling down to writers on the continent,” he says. “Maybe it has for writers in the diaspora, but certainly not for African writers working in Africa. How many speculative fiction writers resident on the continent have adaptations of their books in the works? African writers are not benefitting from that supposed ‘boom.’”

His own work is quickly putting him in a singular position. Last week, at the Hugo Awards nominees announcement, he made three more groundbreaking strides. He is the first African to be named finalist in two categories: Best Editor, for Dominion, and Best Novelette, for Ife-Iyoku, the Tale of Imadeyunuagbon. He and his co-editor Sheree Renee Thomas are the first Black editors to be finalists for Best Editor, Short Form. And he is the first Africa-born Black writer to earn a Hugo nomination at all. And he did these while still living in Nigeria.

Nominated for my 1st Hugo award, with my climate fiction novelette O2 Arena, also a Nebula & BSFA finalist. 🥰🥳

— Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki (@Penprince_) April 7, 2022

It'll make me the 1st African nominated in the novelette category, & the 1st African born, Black writer nominated at all. You can read it here https://t.co/zu3i6uvQ4T https://t.co/ZazfgOnZdR

He believes it is important to speak loudly about the achievements of writers living on the continent, a sermon he puts into practice every time he announces a new accomplishment.

I'll be the 1st writer on the continent to win this 🥰

— Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki (@Penprince_) September 7, 2021

& the 2nd time in a row a Nigerian is winning, both of us the only Africans to have. Congrats to the honours listed writers, esp @RB_Lemberg & Isabel Fall, powerful writers. Thanks to the Motherboard for the amazing honour 💙 https://t.co/nmwzGFIcEO

He notes that there exists an “immense wealth of amazing literature” on the continent, and he praises some of the writers he has worked with—Dare Segun Falowo, Ada Nnadi, Rafeeyat Aliyu, Dilman Dila, Odida Nyabundi, Tlotlo Tsamaase, Tobi Ogundiran, Oyedotun Damilola, Moustapha Mbacke Diop—all of whom, per his estimation, are deserving of more attention than they are getting.

And yet African speculative fiction is not fighting the battle of acceptance and recognition on just the global front. “In Africa, speculative fiction writers struggle to be taken seriously as part of the larger literary community, as being worthy of recognition,” he explains. He has observed that many speculative fiction writers survive the genre fiction snobbery by identifying with “literary fiction,” in a bid to be accepted.

Referencing Tade Thompson’s essay on why it is harmful to always say that African science fiction is “on the rise,” he tells me, “On a lot of levels, African speculative fiction is still rising. That is something a lot of people should realize. The fact that it exists is not enough. Existence is quite different from thriving. That is the case especially for writers on the continent.” ♦

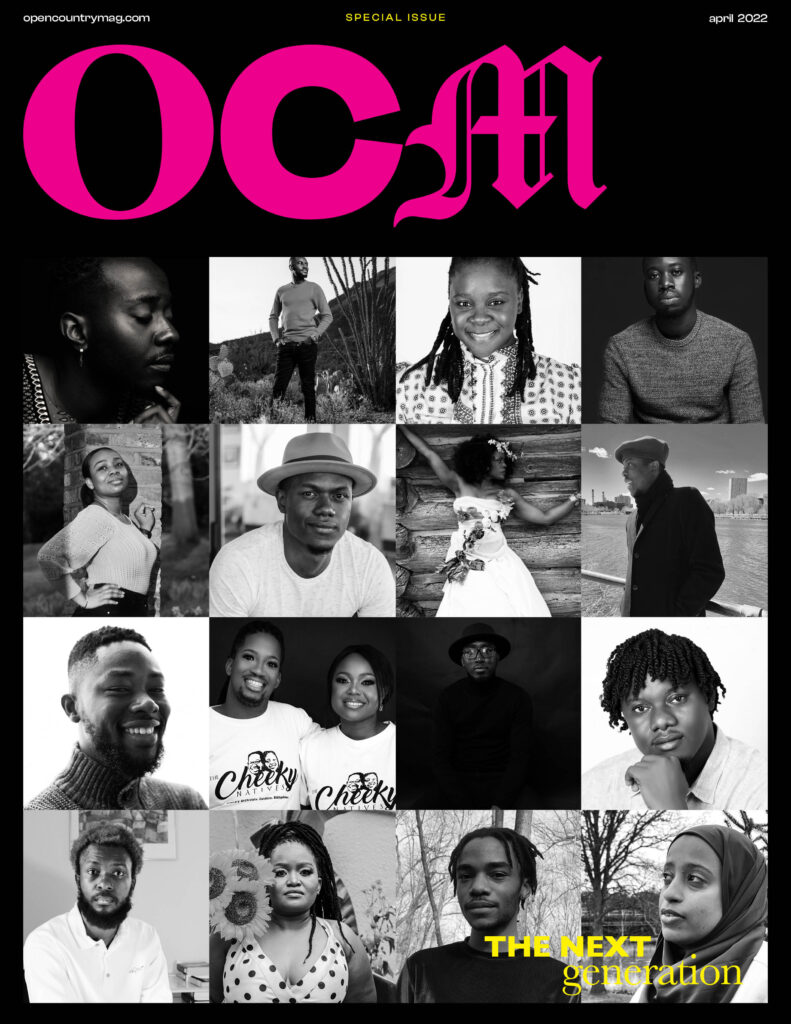

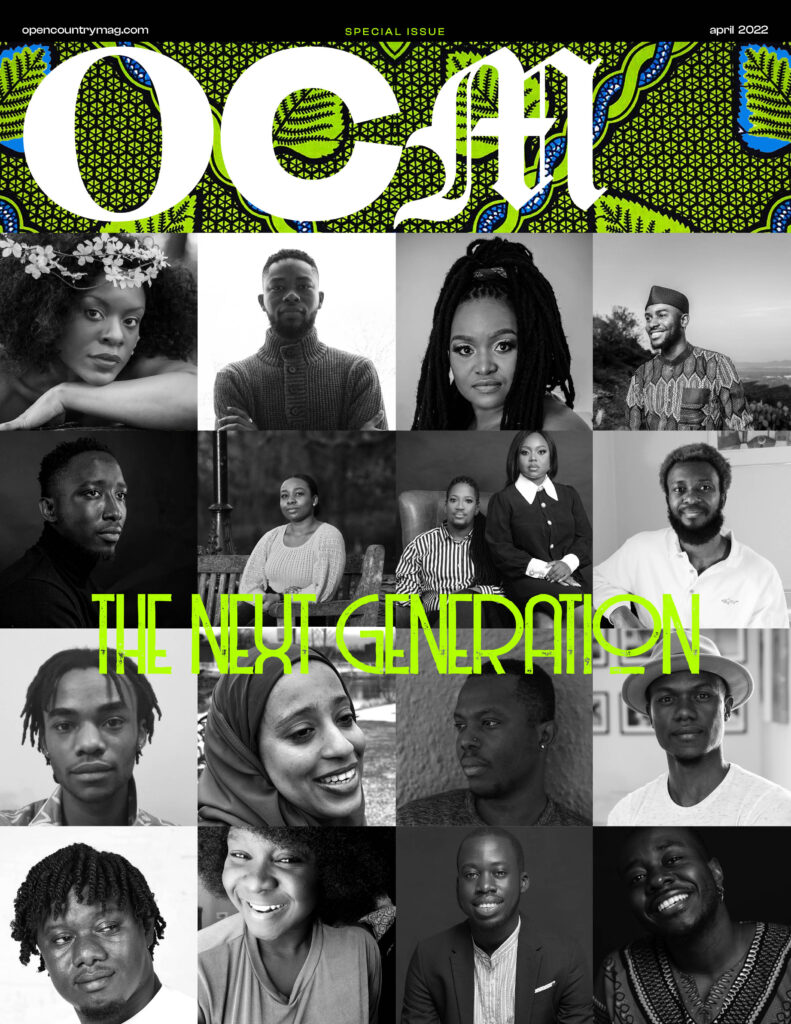

“Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki’s Mission of Anthologizing African Speculative Fiction” appears in The Next Generation special issue of Open Country Mag, profiling 16 writers and curators who have influenced African literary culture in the last five years, curated and edited by Otosirieze Obi-Young. The issue comes with two covers, designed by Emmimade Design Agency.

5 Responses

“…he is the first Africa-born Black writer to earn a Hugo nomination at all. And he did these while still living in Nigeria.”

What’s wrong with living in Nigeria? Is he so eager to leave the country he professes to love forever?