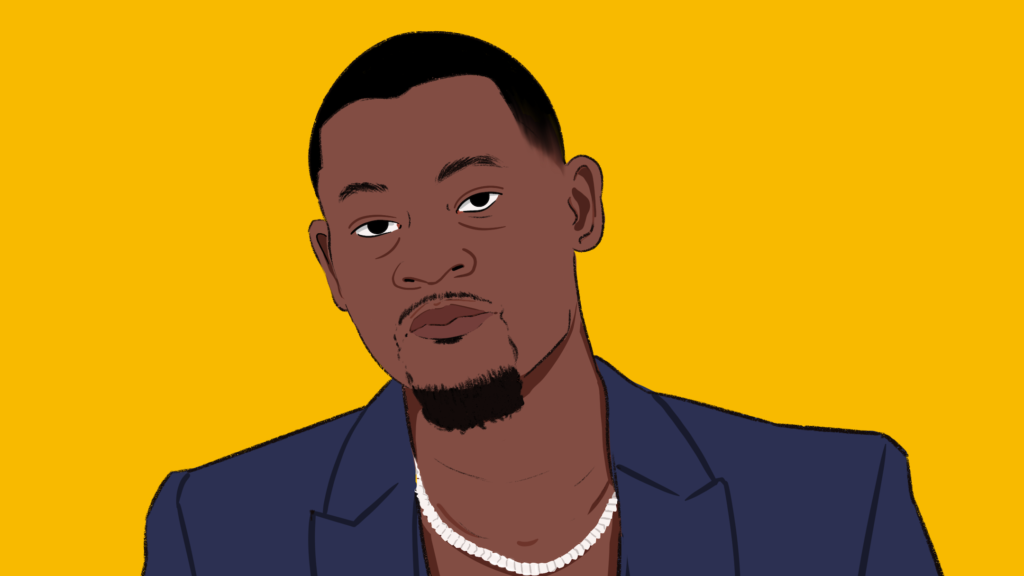

The last interview that Open Country Mag founder Otosirieze did was in 2021, with the South African news site News24. But last week, he returned to sharing his thoughts in public when he spoke to The Republic associate editor Peace Onafuye, for the journal’s “First Draft” series. The writer, journalist, editor, and curator shared his reading habits and recommended some books, but also took on recent literary issues in the African and global scenes.

Here are seven takeaways from the immersive conversation.

On The New York Times’ and Literary Hub’s exclusion of Africans from their “Best Books of the 21st Century” lists:

Think about that for a moment. It means that these people—the New York Times said it polled ‘503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers’ with ‘a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review’—do not think about Africa as an important contributor to global literature. It is naked bias, and I cannot tell which is worse, that they knew or didn’t. . . .

To be clear, I am not asking anyone to include Africans for the sake of ‘representation’, which is a very silly argument in itself; I am stating that some of the very best writers and very best books of the 21st century come from Africa. I am not talking about ‘literary success’— another bad argument for this—but about actual skill on the page.

On African writers not being credited as innovators:

African writers are just not credited enough as innovators, for their adaptiveness to solving problems on the page. When Damon Galgut flits between the first- and third-person in one sentence in his book, In a Strange Room, the acknowledgement never transcends book reviews into literary culture essays or lists. Autofiction is prominent in the American literary discourse, but there are precious few in that genre who write from three continents and articulate culture and politics in the insightful, digestible way that Teju Cole does in Open City and in Known and Strange Things. If a white writer had brought fusion fiction into the discourse as Bernardine Evaristo did with Girl, Woman, Other, they would be on that list.

I have read enough books on that New York Times list and some other books that make lists like that, and when it comes to that blend of serious subject, character acuity, authorial vision, emotional range, and overall artistic merit, I do not know any 21st century English-language novel of literary fiction that matches Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun.

On Africans not recognizing each other by merit:

It is 2024 and Africans should not be begging anybody to be included in anything, especially when the metrics of inclusion are suspiciously para-literary. We should advocate, but no one should be begging. And yet before we demand that non-Africans recognize us, do we Africans recognize each other? Do we write essays and give each other credit when earned? Do we elevate each other by merit? Do we hold up good books as good books especially when written by people who are not friends or in our circles? And that is where much of African literature wobbles. If we do not do that enough, we have no moral authority to expect that others do it for us.

On why he became an editor:

I became an editor for a single reason: to help make space for Nigerian writers of my generation. If the space were there, I would not have prioritized editorial work. I was coming up in the scene and watching my peers come up and form communities, and we needed help getting ourselves into the mainstream. That help was never going to come from an African literary culture that is ageist and classist; it needed to come from us, outsiders in the system. . . . My position was: it was time to bin the notion that a young writer working in Africa could not be a major curator, could not do things that no one else before them had.

On his editing process:

When I edit, I assign myself the responsibility of information: my job is to know more than, or at least as much as, the writer does about their subject. Only then can I be truly helpful. And my idea of being helpful is to present the writer with potential counterarguments; if they could win me over, they would win over the most dissenting honest critic out there.

On what he wants to see writers doing more:

We need more formal essays as we do not have enough of those: pieces that take on ideas and deconstruct how they apply in books, or that look at the scene and identify patterns. That’s one area—and nonfiction generally—where we are not close to the West in any way. I’d just like more of us to truly understand that global intellectual culture is on a faster pace than we have been moving as Africans.

The second thing I hope to see from writers of my generation is sustained critical thinking about the state of Nigeria and Africa. It is precisely what our forebears fought for, a mental space for Africans to think for themselves, and yet we are drifting back intellectually and emotionally to the West and laying waste to a Nigerian ideal. It is true that rampant corruption and insecurity and the breaking of dreams have forced young Nigerians to seek belonging elsewhere, but it is a problem when our new intellectuals speak and all that comes out are ideas that are not about how Africa can be better but about how the West envisions itself. There is a new ‘we’ and they have hitched their allegiance to that, while continuing to mine the old ‘we’ for literary and traumatic material for career-branding. Stop.

On what he hopes for his work to represent:

I hope that when someone looks at what I do, they see the results of belief: that they can believe in themselves and in the culture they come from. No one will fix things if we do not, but first we must confront and try to fix ourselves and whatever beliefs hold us back. I’d say to test yourself, test your ability to create and build against odds. The best gift you can give yourself is a mastery of what you do.

Read the wide-ranging interview in The Republic.