I.

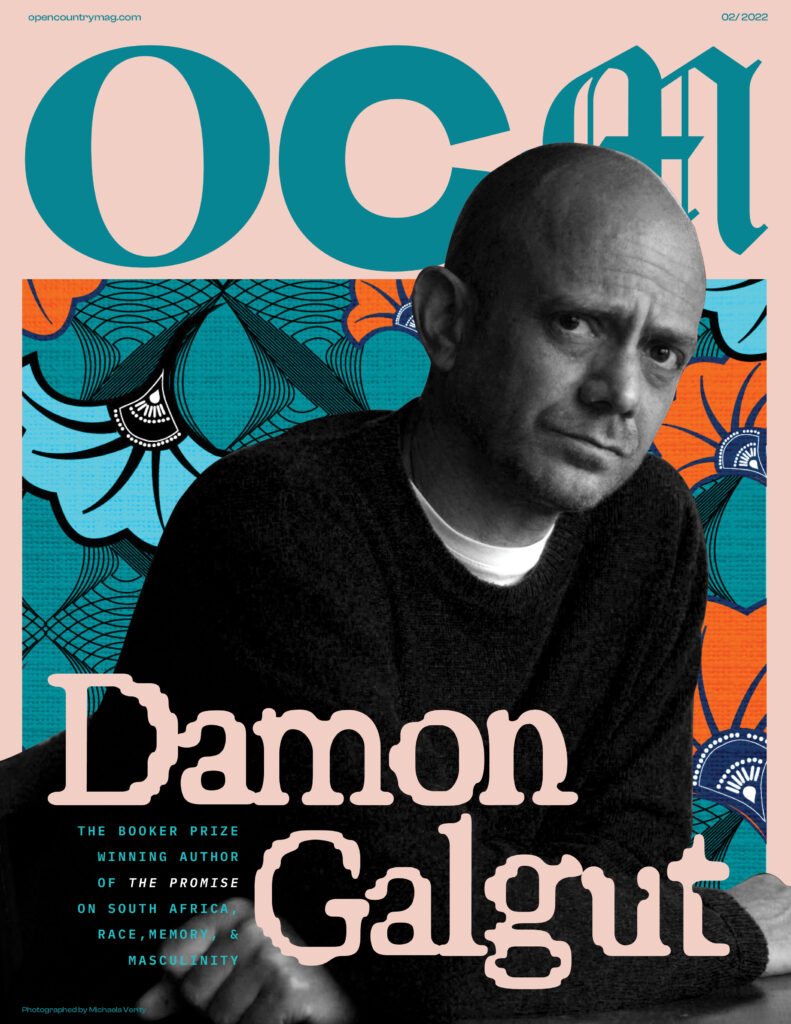

On the days that he writes, Damon Galgut moves to his table with a tortoiseshell Parker fountain pen, the same make of pen he has used since the early 1980s, and opens a big red register, and begins to work, surrounded by bright light. He likes to write longhand. He needs to, because it is the only way he can feel the flow, the train of thoughts organically traveling from his brain to his arm and onto the paper. He enjoys how it takes time, how the process of inscribing words makes him ponder them longer.

A naturalistic thinker and feeler, he sometimes jokes that he is backward. He does not have a TV. His phone has no Internet. His computer is for only typing and emails. He keeps books on the table, which he reads when he is not writing. A change from his younger years when he avoided reading so he wouldn’t be thrown off his attempt to find a voice for the writing. But the books on his table are never by writers who are strong stylists like himself: so wary is he of his hand being hijacked. He holds artistic superstitions: a worry that if he didn’t write for long, he’d fall ill; a fear that if he talked about his work in progress, he’d jinx it. He prefers to take his work as far as he alone can, before sharing it. And when readers open the books, he hopes for them to commit to doing “the work.” He understands that the strongest tradition in literature is for books to offer easy answers rather than ask tough questions, and he resists that convention. He feels that books that offer catharsis raise no moral problems. He is wary of stories that clean up after their conflicts, of the concept of poetic justice. That’s not life as he knows it. What if “good” and “bad” are meaningless terms? What if disorder is the “truth”? He likes when books ask unsettling questions or leave disturbing gaps, so that the reader carries the story around, pondering it. His fiction often has a psychological tone. A critic wrote that it “ultimately evades interpretation.” He takes it as a compliment that people have told him how rattled they are by his work. He is less embracing, though, of some of what observers have called him. “Master of unease.” “The spokesman of the ill-at-ease and the alienated.” As much as he knows his mental landscape, he does not glory in it. It is what it is.

Writing, for him, is “grinding craft rather than lofty art.” He considers it “problem-solving,” whether about logic or plot or tone. Sometimes solutions come to him while writing, other times they come while reflecting. Due to this, he has found himself shrinking away from subjects that require a lot of research. His belief: the writer should aspire to know his subject before writing. His caveat: if the technical requirements of the story demand it, the writer then must research. Without that intrusion, his hand is steady. The evidence of struggle is on the page, and it is important for him to see it.

For nearly thirty years, he carried on with this method, and it yielded seven books. But in the writing of his eighth, Artic Summer, about the British novelist E.M. Forster, he broke his tradition and relied on a computer, to contain and track the enormous research. The story had come to him slowly on a trip to India, where he read Forster’s novel A Passage to India. Curious, he delved into P.N. Furbank’s biography, E.M. Forster: A Life. Its epic, historical scale, covering the novelist’s experiences during World War I and in Egypt and India, impressed him. He was drawn to Forster’s struggles. First to his writing of A Passage to India, which took eleven years, with him feeling stuck for nine of them. Then to his tussle with his sexuality. He couldn’t resist the lure of fictionalizing Forster. Upon his death, Forster had left an unfinished novel he called “Arctic Summer,” and Galgut chose that as his own title.

Galgut opened his novel in 1912, when Forster, buoyed by the financial success of his novel Howards End, undertakes a journey to India, to see his former student Syed Ross Masood, whom he is in love with. A virgin at 33, he is in a sexual crisis, and it is beginning to affect his work in progress, the novel about India. Masood rejects his advance, but their friendship, filled with mutual, affectionate letters, lasts 17 years. Like Masood, Forster’s second great love, an Egyptian named Mohammed el-Adl, also marries a woman.

Although Galgut is gay and had written gay men in his novels, and had more broadly explored masculine archetypes, it was his first time taking homosexuality as a primary subject. He could relate to the suffocation that Forster felt. Growing up in 1960s Pretoria, in Apartheid South Africa, where it was illegal to be gay, he had internalized a sense of concealment, even self-doubt. Later he learned to rethink it: to be an outsider, he decided, is always a position of advantage. In the books before Arctic Summer, there are buried sexual tensions between the men, difficulties in emotional connection. What happens if you don’t express what you are feeling? What are the things not said? What are the things not acted upon? As an artist, it fascinated him to explore the plot that could arise from that inaction. It also wasn’t a thing unheard of, a queer novelist fictonalising an earlier queer novelist: his friend Colm Toibin had done it in The Master, his novel about Henry James, and years earlier, Michael Cunningham had done it in The Hours, his novel about Virginia Woolf, named after the English modernist’s working title for her novel Mrs. Dalloway.

Whenever he begins a new book, part of Galgut’s grapple is to find the story’s voice, a mode different from previous books but consistent in conveying his “authentic innermost call.” He did not think he had arrived at a point where he could say he had his own voice. For him, a book does not come out of style; style takes shape to meet the book. Because of the many defensive personas he developed in growing up, he felt that, at different points in his life, he had a separate interior voice narrating his existence to him. The voice in his last book, In a Strange Room, was shaped by the way that memory functions. With this one, he found that the emerging voice was shaped by Forster’s: lone, estranged.

Forster himself had written that “It is the function of the novelist to reveal the hidden life at its source,” and so Galgut dug in. He could see that Forster’s early novels had fluency and that he’d written them “in a flurry,” and that they had “no sense of the deep internal wrestling” of his later work. Forster had felt constrained writing about heterosexual love, which he did well but knew little about and so had self-doubt, and when he found a love story about men, he felt liberated, and out came the novel Maurice, which only got published after his death. The India novel was his great project and he couldn’t find a way in. By the time he started “Arctic Summer,” which needed a lot of revision for its first chapters, he concluded that he was “dried up.” His nine-year writing block had begun. Galgut, in his own writing, retraced the real story, making sure that the research did not intrude.

He’d started writing it longhand as well, then realised it wouldn’t work because the draft needed continuous inserts; there was so much historical material that it was tough to get all he needed in there. Usually, he only used the computer after the first two drafts had flowed longhand, but this time, he typed all five drafts on the system. When he finished Arctic Summer, he felt like something had left him. He almost felt that he had no more books in him.

There is a moment in Galgut’s life that has stayed with him all these years, and, like several others, sometimes comes to him when he sits down to work. It was in childhood, he might have been four or five, and was reading aloud. He stopped, his mouth was no longer opening, but he could still hear the voice, his voice, ringing in his head, reading words he was not speaking. Excited, he ran to his mother. “I am reading in my mind!” he said to her. He was just recognizing the magical hold of words. It was the first of several seminal discoveries.

The second came at age six, when he was diagnosed with lymphoma, a form of cancer. He underwent chemotherapy until age 11. It changed him, made him introspective, gave him “a sense of being a little apart.” Quietened, he felt on the fringe, listening and observing more than he participated. He became, in his recollection, “a dark and troubled child.” These spy-like qualities, he would later suggest, shaped him as a writer. In that period, too, his mother read to him, and, in his loneliness, stories became a positive space, lighted in him a glow, a promise of comfort.

When he was 12, his English teacher came to class with two books by Roald Dahl, Kiss Kiss and Someone Like You, and read to them. The teacher got in trouble for it. Galgut took Kiss Kiss and found “Pig,” a story of a vegetarian boy who is slaughtered and turned into meat, and the world suddenly looked different. He felt that the boy in the story, Lexington, was him, and that what happens to the boy would happen to him, too. It was like he had found a secret: Literature did not only soothe and entertain, it could disrupt as well. This, the pursuit of disruption, became a lifelong guide. He embraced more singular authors: William Faulkner, Patrick White, Virginia Woolf, Samuel Beckett.

He started writing, first long stories, then two novel manuscripts, the first of which was a mashup of Lord of the Rings and a Wilbur Smith adventure. Then he wrote a third novel manuscript. He was 17, in his last year and a half at Pretoria Boys High School, where he was head boy, and he wished to be published. He showed it to his Afrikaans teacher. She liked it and mailed it to publishers.

The editor Alison Lowry received a copy at Jonathan Ball, then a new press. Even though, unlike many submissions, it came with no query letter or synopsis, she opened it and read it in one sitting. She knew she wanted to publish it. Her boss, Jonathan, was unsure: his core interest was nonfiction, political history and current affairs, and he didn’t think they should be taking a 17-year-old schoolboy’s book seriously. “What’s so special about it?” he asked Lowry. She tried to explain, and she said, “Trust me.”

“As a reader, editor and, later, a publisher myself, there is no feeling quite like reading a new work and recognising talent,” Lowry told me. “Sometimes it is just a glimmer, a flicker; sometimes it shines up from the page like a beacon. That the author was 17 and fresh out of school was not the reason, although it was certainly unusual for someone so young to have written a publishable book. But I was struck by two things: a fearless candour and maturity in his approach to complex, even quite dark, themes; and the freshness and originality in his creative expression and use of language.”

She invited Galgut to their office. “I remember looking up from my desk and there he was in my doorway, a somewhat shy, apologetic smile on his face and a broken sandal in his hand. ‘I’m not usually this disrespectful,’ he said, or words to that effect, ‘but it broke on my way up in the lift.’ From then on we met regularly to discuss his work, or just to talk really, over coffee or lunch, and a deep friendship developed. I think early on I might have felt protective—he was very young and the media focused a lot on that aspect, rather than on engaging properly with his work, which he understood but found frustrating. For Damon it was always about the words on the page rather than the personality who penned them. It’s still that way.”

Published in 1982, when he was 19, A Sinless Season is set in a reformatory, where the arrival of three boys sets off a murder. The writing was verbose but held promise. People were intrigued at the emergence of a teenage talent and the novel became a minor word-of-mouth sensation. Penguin picked up its U.K. and U.S. rights. In a review, three years later, Kirkus Reviews called it a “Portentous juvenilia—moodily promising here and there, but muddled in its adolescent stew of themes and frequently embarrassing in its amateurish prose.” The magazine went on to note its “murky meditations on pain, death, suffering, and sexual confusion.” Yet for Galgut, now recognized as a prodigy, the road seemed wide open, free of hurdles.

In the late ‘80s, he traveled around Europe, South America, and the U.S. In London, he did odd jobs to fund his movement: he worked in an antique shop, worked for a catering company, and modeled nude for life drawing classes, earning £6 an hour but becoming in demand because he could sit still for long.

Back home, the anti-Apartheid movement was gaining steam. Having grown up in Pretoria, the nerve center of Apartheid, with an atmosphere of institutional authority and rectitude, and now studying at the University of Cape Town, a hotbed of alternative thinking, leftwing in its politics, he was drawn to student activism.

In 1986, a state of emergency was declared in the country. The media—newspapers, television reports—were censored, and the country floated in an airlessness of information. Students were arrested and detained, for such things as painting graffiti on a wall at 2 a.m. Galgut was still naïve, in that white liberal bubble where he needed to feel good about himself and his sense of justice. He attended student protests, and, at one march, the police beat them and ripped clothes off some people on the ground.

Nights later, at the family dinner table, he shared what happened and got into an argument with his grandfather, a judge. “Nonsense, they don’t do that,” his grandfather said. “If they hit you, you must have done something.” That argument opened Galgut’s eyes to the deleterious extent of systemic injustice; reality was not what most white people were seeing. Years later, he would say of that argument, “My family were not raging racists, but they were fairly comfortable with the set-up.”

But his grandfather wasn’t the only problem in his family. His stepfather had been violent and abusive, and the environment, coupled with his cancer diagnosis and character change, turned his childhood into “a bit of a war zone.” He entered adulthood with a dim disposition, and it took him years to shed that.

He was not surprised that when he began to write the five stories that became his second book, Small Circle of Beings, the spectre of family hovered and haunted, and became the main subject. The title itself refers to the family unit, and the title novella lifts from his own life. In it, a nine-year-old is on his sickbed, and with him is his mother, whose perspective frames the story. The boy’s parents are selfish—his farmer father is emotionally distanced and his mother will not take him to the hospital because she does not want to leave their house—and yet it is also a story of how parents deal with potential loss.

The other four short stories—“Lovers,” “Shadows,” “The Clay Ox,” and “Rick”—also explore familial dysfunction and politics, parental abuse, and domestic violence. He was putting under focus the mechanics of human failings and the aridity of dishonesty. The critical response to the book gratified him.

Family again underpinned his third book, a novel called The Beautiful Screaming of Pigs. The narrator is a 20-year-old man named Patrick Winter, who had been in military service in Namibia for two years and now returns to the country, with his mother Ellen. They both have separate and connected histories. Patrick’s millionaire father divorced Ellen years ago, and now Ellen is here to see her latest lover, Godfrey, a Namibian man 17 years younger. For Patrick, the return brings memories of his first and only love, a man he fell for on his first visit. He bears another gash: the death of his brother. Galgut had begun creating layers in his fiction then, and their journey to the capital city of Windhoek became another trip: into their pasts.

Beyond the family’s bond, Galgut engaged an aspect of white privilege, a level of white justification, so the book became about their search for answers. It is 1989. Namibia is on the verge of its first free elections. In Windhoek, the idealistic Godfrey works for the independence movement, the South-West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO). Patrick’s time in the country was spent waging war on behalf of the minority white South African Apartheid government. As he travels with his mother, he wonders who among the people working to have a new country he might have shot at.

Patrick carries emotional trauma, has panic attacks, and takes Valium twice daily, and we follow his reckonings with his time in the military, his childhood, and his realization that his sexuality is not what he has taken it to be. His feelings of being an outsider draws him close to a young Afrikaner man, Lappies, with whom he falls in love without recognizing it. We learn that it is Lappies’ death that triggers his mental breakdown, which sees him discharged, sent back to South Africa, and hospitalized.

Patrick deems himself a deficient man, and aspires to an archetype that his father, brother, and Godfrey all fit into. As a child, he would rather sit speaking to his mother than play rugby or go hunting. You’re in love with your mother, Godfrey tells him, oblivious of Patrick’s growing mental attachment to him. Through his eyes, we see the complications of affection. Lives are meant to be separate and apart, he ponders, when the borders break and we overflow into one another, it only leads to trouble and sadness.

The Beautiful Screaming of Pigs expanded Galgut’s subjects. It was his most political work and it set the tone for his critique of masculinity. From then on, his protagonists would all be men, unsure of themselves, unconvinced of their place in the world, men who are physically not the most imposing, men who are figuring out their sexuality. When the novel came out in 1991, it won the Central News Agency Literary Award. Yet it did not receive a level of interest reserved for major works. It was a confirmation of something that Galgut had begun to suspect: his career was stagnating.

Galgut tells me that being published as a teenager was not entirely enriching for him. “Suddenly, having that attention on you at that young age is very—it makes you incredibly self-conscious, and I was already a very self-conscious person,” he says. “It had a very stifling effect on me, so I really struggled to find my feet.” Lowry told me the same thing: “It can work against you. I think he had to work hard to disprove the ‘one hit wonder’ attention.”

The pressure was so great that, in the six years between A Sinless Season and Small Circle of Beings, he attempted and failed at writing two novels. That he finally succeeded with Small Circle of Beings, a collection, was only because he fell back on the personal.

He shares that his childhood illness affected his parents’ breakup. “I mean, I think their marriage would have ended in divorce, but it sped up that process by magnifying their differences to each other and placing them under stress.”

As a teenager, he began taking long walks, just to evade the climate at home. It became tied to his writing, became the time he set aside for thinking about ideas. Years later, as an adult, he would take even longer walks to rid himself of unease, preferring to go anywhere he could on foot.

His parents were nevertheless in agreement on one thing: his future. They hoped he would maintain the family tradition and study law. It was a time of pressure and tension for the young Galgut, who had already taken interest in prose and drama. For his father, acting was “just a joke.”

It was while studying acting—a performance diploma in speech and drama at the University of Cape Town—that he started to write plays. A year after A Sinless Season came out, his first play, Echoes of Anger, was produced at the State Theatre in Pretoria in 1983. It was an average effort. He was invited to be a resident playwright at the Performing Arts Council of the Transvaal, and there he wrote a second play, Alive and Kicking, which was performed in 1984.

“It’s not a play I’m especially proud of at all,” he says. “In fact, I think it’s a sketch of a play, not a play.” Later, fed up with the institutional atmosphere of the residency, he left. “I also thought if I want to write plays I should go to drama school and understand the old business of making them.” Looking back, he does not think that the diploma at Cape Town was useful. Rather than specialize in directing, he chose acting because he thought it would help him write better plays. It had the reverse effect.

In 1986, his third play, A Party for Mother, was a success, winning the SACPAC Award. He was excited, young, and receptive, and at the Market Theatre in Johannesburg, which had a mixed-race audience, he felt “alternative possibilities in South Africa.” But by then, theatre was already in decline and the government was cutting sponsorship.

“We have to understand something in particular about South African theatre,” he explains, “which is that it flourished as a theatre of resistance under Apartheid. Theatre was really a powerful force, and exciting, which is what got me stirred up. After ’94—it’s not something I really understand—but theater just, it’s like it switched off in South Africa. And the audiences also fell away. The drive to produce anything really sort of interesting or unusual seemed to lose its focus and then the funding dried up. In a large way, it contributed to me losing interest.”

When his attention returned to production over a decade later, it was to film. His fourth book, The Quarry, was being adapted. The 1995 novel, even with a second movie adaptation in 2020, is considered a minor work in his oeuvre. Plotted like a cat and mouse dance, the story has a fugitive on the run. He set it in a rural region, and against the grassiness of the veldt, the characters move with intensity. His concern: freedom in a state of desperation. The Quarry did not get published outside South Africa. He would not find an international readership until eight years later, in 2003, with the release of his fifth book, the novel The Good Doctor.

II.

Internationally, the year 2003 was important for South African literature. For most Anglophone observers, the country’s literary reputation rested on the great white writers: Nadine Gordimer, J.M. Coetzee, and André Brink. For a long time, major international recognition was a one-two combo of Gordimer and Coetzee. In 1974, Gordimer won the Booker Prize, for The Conservationist, and Coetzee followed, in 1988, with Life and Times of Michael K. Three years later, in 1991, Gordimer received the Nobel Prize in Literature. Eight years afterwards, in 1999, Coetzee became the first writer to win two Booker Prizes, with Disgrace.

Behind the scenes, publishers were keen to develop a local list. To actualize this, Penguin South Africa hired Galgut’s longtime editor Lowry, in 1989. By the time she became its chief executive officer, in 2002, she was preparing Galgut’s next novel for release.

The Good Doctor takes place in a dysfunctional hospital in rural northern South Africa, where two doctors, the young, idealistic Laurence Waters and the older, conservative narrator Frank Eloff, butt heads. It is a classic clash of idealism and traditionalism, exacerbated by generational gaps. Yet both men, guided by their sensibilities, are incapable of understanding the expanse of history they are operating in. Laurence believes in changing the country; Frank doesn’t see how it is possible. Frank’s cynicism comes from personal and professional disappointments: his wife has left him, and he comes to the hospital only to find it in a sorry state, and then he does not get the promotion he was promised. And then comes Laurence with his optimism.

Galgut wanted to show the distance in generational memories. When he taught at the University of Cape Town, a student once told him that he would have liked to serve in the army, that it would have been a formative experience for him. He could see that the student was romanticizing what military service meant; it did not occur to the young man that soldiers had to kill people. He himself knew: his generation was the last to undergo compulsory military service. He put this in the book, and Laurence tells Frank the same.

“Some of my more unkind friends might say that Frank is me,” Galgut would later say in an interview with The Guardian. “It’s partly true.”

The Good Doctor was his career gamechanger. It won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best Book, for Africa Region. When it was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, bookmakers placed it as the third favourite, and one critic, Robert McCrum in The Observer, tipped it for the win. There was one hiccup, though: the book was not readily available, and it took some time before copies arrived and it could be displayed with the rest of the shortlist. Oxonian Review summarized the problem thus: “This may have had more to do with Galgut’s publishers than the bookstores, but it also reflects the novel’s marginal subject matter and its author’s marginal status.”

His lesser standing and younger age brought a new narrative: comparison to Coetzee. “If there is a posterity,” the novelist Rian Malan wrote in an igniting blurb, “The Good Doctor will be seen as one of the great literary triumphs of South Africa’s transition, a novel that is in every way the equal of J.M. Coetzee’s Disgrace.” The older novelist, longlisted for his Elizabeth Costello, had been left off the shortlist. For some, Galgut was why. The Guardian wrote: “If, as seems the case, the British publishing institution has a limited number of slots for South African writers at any given time, and if the Booker is anything to go by, Galgut is moving into the Coetzee slot.” A third South African had also been on the longlist: Barbara Trapido, for her Frankie & Stankie. The prize went to D.B.C. Pierre’s Vernon God Little, but U.K. critics had welcomed the new South African contingent. By the end of that year, Coetzee would receive the Nobel Prize, putting more attention on the country’s literature.

Galgut, while appreciative, was not fully welcoming of the Coetzee comparisons. “People know relatively little about South African writing,” he said last year. “So they reached for figures that are immediately iconically recognisable, and have dominated the literary landscape for many years. There’s a certain satisfaction, I have to say, in thinking that perhaps at last, I have managed to carve out my own ground in this respect. And that people may think I have a voice of my own as opposed to just being another tortured white man from Cape Town.”

To capitalize on his newfound acclaim, his publishers reissued The Beautiful Screaming of Pigs, which had fallen out of print. He had never been satisfied with the original edition; he felt that the prose was “discordant”; and he tweaked it.

He had also begun work on a new novel, which he was calling The Impostor. It continued his method of masculine duality, placing it at the crossroads of class and a racially altered country. Its protagonist, Adam Napier, an ambitious, unemployed, confused poet from Johannesburg in his 40s who moves to a rural town in the Karoo, and the man he meets, Canning, a wealthy heir of a game reserve, enter an entanglement. Canning tells Adam that he saved his life in school, but not only does Adam not remember the supposed incident, Adam does not remember Canning as well, even though the man knows his school nickname, but Adam presents that he does. Underneath his timidity, Adam is seething. He came to the Karoo because he has been fired at the office to make space for a Black intern. He is, he believes, a “victim of Africanisation.” But spending weekends with Canning, he becomes enamoured by his host’s wife, a younger, Black woman. As he is sucked into the Cannings’ world, The Impostor, ultimately a story of murky intents, lays bare the bestial hold that materialism has on the South African dream.

I asked Lowry what traditions in South African literature she believes Galgut to be working in. “I think it’s difficult to categorise or define a ‘tradition’ when it comes to South African literature,” she replied, “and I’d hesitate to impose on Damon’s work what sounds like a constriction—or construction, for that matter.” His very flexibility across fiction, drama, and poetry shows that, she said. “I would say that his strength lies more in his individual voice and with how dexterously he uses it than in being representative of a collective of voices.”

After the arrival of The Good Doctor, Galgut’s method changed. Perhaps aware of his difficult path, his fiction became self-referential, more post-modern. It showed in The Impostor, in a scene where the narrator sees the initials D.G. carved on a desk, and is haunted by it, unaware of who the person could be. But before The Impostor, Galgut wrote a long narrative, told by a voice that flits between third-, first-, and second-person, a man named Damon, who could be himself or not. He has always been inclined to detachment from his own experience, to revisualizing his world, observing himself from outside himself, like watching a film.

He started the story in the third person, with the idea of pulling back, observing the two men walking towards each other, and then zooming in. But something else happened: a first-person voice slipped in, a vantage that changed little from the third-person, a switch he recognized as his own lived experience. It was unconventional and it delighted him. One thing that irritates him about a narrative voice is that the writer must commit to their chosen voice. With The Good Doctor, he would have loved to see the story more than just through his narrator’s eyes, but it was the first-person voice and he had to stick to it. (He avoids the omniscient voice because he prefers stories that are particularized.) He had been wanting to break this rule—why couldn’t he now?

In the narrative, this Damon is on a walk in Greece, and later in Lesotho, with a German man, their relationship tinged with homoeroticism. Galgut titled it “The Follower” and sent it to The Paris Review. When the editors at The Paris Review received the piece, they labelled it “fiction,” and published it in 2005. The magazine published two more similar pieces from him—“The Lover,” in 2008, and “The Guardian,” in 2009, both also labelled “fiction.” He did not oppose the label; in fact, he was happy with it because it recognized what he felt was the subject of the narratives: memory—an everchanging quality that is, in its instability, the very voice of fiction.

The three narratives, each roughly 60 pages, formed his seventh book, In a Strange Room, subtitled Three Journeys. (It took its name from a line in a book that Damon reads, Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying: In a strange room you must empty yourself for sleep.) His narratorial voice had deepened. His geographical canvas, which until then had been restricted to South Africa and Namibia, enlarged. From Lesotho in “The Follower,” the narrating Damon appears in Kenya and Europe in “The Lover,” where he befriends three French Swiss backpackers, one of whom he has feelings for, and then moves to India in “The Guardian,” with a woman unsure of her life, his friend’s lover now on the verge of suicide. The landscapes he passes—Zimbabwe, Malawi, Tanzania, Switzerland—are described. “I doubt,” Jan Morris wrote in a review, “if any book in 2010 will contain more memorable evocations of place.”

Damon is moving because he is unhappy, and he is distant from his companions. In the third-to-first-to-second-person blur, he reads like one in search for an identity, but unwilling to trade even that for a definition. The “he” describes him from afar; the “I” buts in with doubts and clarifications; the “you” inverts the thrust of his thoughts; and still they achieve a flow. In one moment:

He sits on the edge of a raised stone floor and stares out unseeingly into the hills around him and now he is thinking of things that happened in the past. Looking back at him through time, I remember him remembering, and I am more present in the scene than he was. But memory has its own distances, in part he is me entirely, in part he is a stranger I am watching.

In another:

He spends a day in a gallery of outsider art, paintings and sculptures made with the vision of the mad or the lost, and from this collection of fantastic and febrile images he retains a single line, a book title by a Serbian artist whose name I forget, He Has No House.

The gaps in self-knowledge amplified by this technique is supplemented by the story’s form in print, which leaves spaces between portions of prose, like an invitation to the reader to fill. Without quotation and speech markers, it reads, on some pages, like thoughts floating, tied but not trappable to context. And the effect is that Damon’s growth as a character comes in how he observes his distances. (In The New York Times, Adam Langer points out that “Damon” is an anagram of “Nomad,” and that “Noel,” a name that someone mistakes as Damon’s, is same for “lone.”)

Galgut’s intention with In a Strange Room was to cover the three primary forms of human relationships and how we fail at them. In “The Follower,” power; in “The Lover,” love; and in “The Guardian,” guardianship. But he wasn’t interested in spelling these out; he wanted the reader to sense them the way he had. Thematic unity isn’t something that he logically thinks about; he only feels it as the architecture of storytelling builds.

The longlisting of In a Strange Room for the 2010 Booker Prize prompted observers to wonder about its classification as anything other than a fictional memoir. The editor Claire Armitstead tweeted: “Is it a novel?” But the reception was uniformly enthusiastic. The Guardian wrote that Galgut was “at a superb new high.” The book reached the Booker shortlist, where bookmakers installed it as the second favourite, and one placed a £400 bet on it to win—the biggest single bet on a nominated book in years. The award went instead to the longshot outsider, Howard Jacobson’s The Finkler Question.

Galgut later addressed the question of classification. “The memory of any moment or event is made up of a disparate jumble of impressions and perceptions, out of which we pick in retrospect what we think of as the ‘central’ or ‘meaningful’ ones,” he said. “And we do this far more keenly when we link events into a narrative. One thing leads to a second thing, but the links are a form of meaning we bring after the fact. We raise certain memories into prominence and drop others out of sight to serve this purpose. All of us do it, all the time, making up the stories of our lives as we go along. How is this different to the fiction writer creating meaning? I believe that we construct our memories in the same way that a story-writer constructs a fiction.”

He told Conjunctions, “I guess what the book is doing is pitching you into the kind of the unstable nature of memory itself. It’s pushing your face into the way memory doubles back on itself and corrects and is continually unsure of itself. It’s full of holes. I’ve tried to be honest in the telling where, if I don’t remember something, I try to reflect that.” He added, “If I had to distill this particular book to a sentence it would be that all consciousness is memory and memory is fiction.”

In this sense, Galgut is a distant kin of the Nigerian writer Teju Cole, whose breakout books, 2011’s Open City and 2007’s Every Day Is for the Thief, are, like In a Strange Room, memoiristic fiction about places. To write their way out, both manipulate the inadequacies of genre itself. But unlike Cole, Galgut’s burden of meaning is placed not on the individual, intellectual, and historical, but on the relational, emotional, and existential.

In a Strange Room was the first book that Galgut set mostly outside a discernibly South African identity. Galgut, Ben Williams suggested, “is trying to escape from, or at least disengage with, South African identity politics in this book.” Williams notes that reviewers in the country have not used the phrase “South African novel” to describe it, even if a few see the narrator as occupying “a state of being that’s extraordinarily relevant” to the country. Damon may be South African, but his experiential economy, Williams goes on, is “seeking to tease out truths on a plane of higher, less constructed contingencies.”

The reviews surprised Galgut. Here he was, writing away from national ties, only to read that the very atmosphere of unrootedness he created fit his country’s emotional climate. “I guess if you are digging into the stuff of your own psyche you’re going to be laying out whatever’s in there,” he said to Conjunctions, “and I am South African. It’s more in relation to other people, other travelers, that the Damon character realizes he’s not like them. In other words, the definition of being South African is a negative definition”—Damon defining himself by what he is not.

Almost ten years later, Galgut told Daily Asian Age, “It was a way for me to remain a South African without having to feel answerable to the usual set of South African questions, which I can tell you often feels, in a literary sense, very tedious indeed.” It was, he added, “a huge relief to be free of history for a while.”

Yet there was an irony to this that Galgut knew. Memoirs were popular in South Africa, a country yearning for untold stories post-Apartheid, and yet the first time he decided to write a work of memoir, he chose to set it outside the country. But it didn’t bother him. He was a white male and the voice of his demographic had never been subdued; their life had always been in public; his memories were not important to the national reclamation; what was there to write about? In a time when history and politics were the zeitgeist, he had chosen his place: reaching for the essence of consciousness itself. And it was a choice borne of privilege.

“If I’d been born in a country whose recent history was more placid than South Africa’s, I think I would be a very different kind of writer,” he later said. “My subjects would have maybe been far smaller, more limited. But there is a kind of expectation of South African writers that we should in some way be accounting for this awful history we’ve been through. And yes, it does feel unfair because I didn’t make the history, after all; why should I be speaking for it?”

By this time, it was another country that Galgut preferred to be in physically and mentally: India. He had been lured there by yoga, and was now visiting the country frequently. Part of what attracted him was anonymity. He was trying to avoid a social presence anywhere: knowing people, having neighbours be familiar. Being so far away from South Africa gave him some perspective, and India drew him with a sensory invasion, a stimulation that fired up the writerly side of his brain. It was there that he wrote most of The Good Doctor. He went to the mountains in the north of the country, then stayed by the sea, loving the warmth. He couldn’t swim but he took walks on the beach in Goa. At the end of the day, when it got cooler, he came inside to write. He sorted through research on E.M. Forster, thinking of the novelist’s work and love lives, how his travails almost a century ago echoed his own. The questions on his mind: What happens if you don’t express what you are feeling? What are the things not said? What are the things not acted upon?

In 2014, the year Artic Summer came out, a blogger reviewed Small Circle of Beings, 26 years after it was first published, and wrote about Galgut: “I don’t understand why he is not celebrated.” Galgut, though, had a more pressing problem. What if this book he had broken his own writing rules to finish, this book about a dead writer named after his unfinished work—what if this book were his last?

III.

Damon Galgut is acutely aware of endings, and all of his fiction, on some level, deals with death. There are avoidable murders in A Sinless Season and The Impostor. A child is dying in Small Circle of Beings. An animal slaughter gives The Beautiful Screaming of Pigs its name. The Good Doctor is set in a hospital. Cemeteries appear in The Quarry and In a Strange Room. His childhood lymphoma and chemotherapy had given him an early awareness of mortality, and he was rationalising it in his work. So it was fitting that, three years after Arctic Summer was published, it was in a conversation about funerals that the idea for a new book came.

He met a longtime friend in Cape Town. Over drinks, the man told him that he was now the last surviving member of his family. Then he began to tell him about the family funerals: for his mother, his father, his brother, and then his sister. It would have been too grave a story, but his friend was a funny man who was now drunk, and he humorously related details. The tragedy and hilarity of his telling made Galgut think. What if he wrote this? A story of a family coming together for funerals on four different occasions. What if he used this to explore time and the passage of time? He could write this.

He separated the funerals across four decades. Each would last just a day or two, but what those snapshots could reveal about the family’s history, how the characters could change in those jumps in years, how the country itself would have changed. He had explored memory in In a Strange Room, but what he could do with time—how he could take a closer look at aging and closeness to death.

He needed a way to make each funeral different, so he looked to his own family history and made the characters converts of different religions. His father had been Jewish. His mother, who converted to Judaism, got remarried to an Afrikaans man who was Calvinist. He included Catholicism, and then New Age, because it represented the dissatisfaction in orthodox worship.

While mapping the characters’ interactions, he remembered another family story that a different friend told him. The friend had grown up on small holdings outside Pretoria, and his mother, on her deathbed, made their family promise to give a little piece of land to a Black woman who took care of her during her final illness. But decades passed and the family did not fulfil the promise, until they finally did. Galgut realized that this was what his novel needed: a thread of conflict to link the funerals. It made even more sense considering that, in real time, South Africa was seeing a renewed calls for land restoration to Black people. In the book, he made the family promise to give a house to the Black woman who served them, a house on a piece of land that would cost the family little. The internal tussles of the family he created, the Swarts, became a symbolic conduit for a heated national question, and the family’s daughter, Amor, its moral centre.

His working title for the novel was “Dark Love.” He’d taken it from Amor’s Afrikaans name, based on the notion of loving one’s country only in a dark way. In Amor, Galgut’s childhood terror reincarnates: she is struck by lightning at age six. He went further: Amor is ten when her mother dies. He sliced her, and her entitled brother Anton, out of his own dual awareness as a white South African. Amor overhears Pa make the promise to Ma, and what she wants to give up, Anton wants to keep. To explore his own artistic insecurities, he made Anton a failed writer, working on a tragicomic novel about a family and farm.

Soon he ran into a problem. The narrative he had set up was now frustrating. He wanted to have a chorus of voices, something discordant that signified the multiplicity of the South African experience. How would he do it?

Meanwhile, he had real life problems: he was in a tax fix. Fortunately, a filmmaker acquaintance who had been interested in making a second adaptation of The Quarry came calling. He needed money badly and needed more. Reluctantly, he left the book and took up work on another screenplay, which became Moffie, the 2019 romantic drama with two military men in South Africa (the final draft contained only about five percent of his script, though). It was in the course of writing it that it clicked in his head: the solution for his problem of chorus. He could move swiftly between characters like a camera, between points of view like he did with In a Strange Room. He had been doing this in scripts over the years; why did it never occur to him to do it in a novel? His sole worry: what if it threw readers off? He stuck with it. The major change he went through with was in the title, changing it to The Promise.

Upon publication last year, The Promise instantly became Galgut’s most acclaimed book. The technique became what many readers praised. Edmund White, in a blurb, called it “the most important book of the last ten years.” In Harper’s, Claire Messud wrote, “To praise the novel in its particulars—for its seriousness; for its balance of formal freedom and elegance; for its humor, its precision, its human truth—seems inadequate and partial.” In The New Yorker, James Wood compared it to Joyce and Woolf and praised the narration as “beautifully peculiar.” The novelist Garth Greenwell wrote, “For formal innovation and moral seriousness, Damon Galgut is very nearly without peer. The Promise recalls the great achievements of modernism in its imagistic brilliance, its caustic disenchantment, its relentless research into the human.” In The Guardian, Anthony Cummins mentioned his two Booker Prize shortlistings, and added, “Don’t be surprised if Galgut goes one better this year.” Five months later, little over a week to his fifty-eighth birthday, Galgut won the Booker Prize.

The upper strata of literary acclaim can be surprising territory for the self-possessed, even for those writers who flirted with admission to it and so must have a certain level of expectation, so all of this—the press rounds, the interviews, the variegated answers to the same questions—bemuses the introverted Galgut. We are speaking in late December, weeks after he won and over a month after he agreed to do this story, and he is reflective and clear-eyed about his journey.

“I’ve never seen my career as a, you know, a progressive escalation with a crowning moment that should lie at the peak of it,” he tells me. “That’s not sort of how I’ve experienced things. I mean, I’ve had quite some upside-down experiences in a way, because I think I started out with some attention and success because I was so young. And then that kind of faded, and my career really kind of went into bad decline and then it came back again in an unexpected way, so, uhm, it’s gratifying, any kind of acknowledgement.”

Lowry said, “I think for some years Damon had a more positive reception abroad than at home, but perhaps that is more reflective of South Africa not being over celebratory of the arts in general than a snub to his work. Literary prizes do not do all that much for book sales in South Africa, with the Booker being the exception.”

After its shortlisting, The Promise was the red-hot favourite. A week later, The Bookseller reported that it sold 8,884 hardback copies—a 241% increase. After it won, it topped the Nielsen Bookscan chart in December. One of the judges, the Nigerian novelist Chigozie Obioma, himself a two-time finalist with his first two novels, said that the book is “a testament to the flourishing of the novel in the 21st century.” The panel’s statement called it a “spectacular demonstration of how the novel can make us see and think afresh.”

After all these years, he has finally nailed a novel that is both a critical and commercial hit, and still he is not taking the fanfare too seriously. “I think it would be dangerous, if I can put it like that,” he says. “The writer in me thinks that sitting down to write the next book is going to be exactly the same as writing the last one and the one before that. And in a way, the more open you are, you know, to seductions of the ego and personal prestige, the more difficult it becomes to enter that other world where you have to go to make a book happen.”

He is practical about his profession. At the ceremony, with almost all the representatives of the publishing industry listening, he used his moment to beam light on his continent. “This has been a great year for African writing,” he said, referring to the fact that several major international awards—the Nobel Prize, the International Booker Prize, France’s Prix Goncourt, Portugal’s Cameos Award—had gone to Africans. But he was also speaking to the industry’s unacknowledged dismissal. “I’d like to accept this on behalf of all the stories told and untold, the writers heard and unheard from the remarkable continent that I come from. I hope people will take African writing a little more seriously now.”

But Galgut’s inclination to speak to the world as he sees it does not meld into easy resolutions on the page. Something he wanted with The Promise that hasn’t quite landed is his depiction of Salome, the Black woman whose betrayal by the Swarts family glues the story. His decision to show her as the family sees her—present but invisible, without a voice in a story of white people about her—has raised questions.

“I mean, obviously it was a question I had to consider; do I give the same treatment to the Black characters in the book that I do to this white family?” he told the Zimbabwean writer Bongani Kona. “Do I go into their heads in the same kind of loose way that I’m moving between the white characters? And then I thought, I’m writing primarily about white South Africans in all their limited vision of the world, and part of those limits is what they know, or rather, what they don’t know, or choose not to know, about the Black lives that cross their paths every day.”

He’d defaulted to his family experience, how his parents did not ask about the lives of Black people who worked for them in Pretoria. His intention was for her silence to question the blind spot in the white South African psyche. He told Indian Express, “It’s simply a brutal, unpleasant truth that White South Africans in general do not perceive the lives of Black South Africans around them as full and human in the way that they would see the lives of other White people. So, I wanted to convey that in the narrative itself.”

He admitted the “political risk” in his decision, but also said that he wasn’t pressured by “the threat of identity politics.” He told New Statesman, “I very, very much believe that it’s the premise of all fiction that you imagine how it feels to be somebody else, and that right is supreme.”

His view got me thinking about Toni Morrison’s on her first novel The Bluest Eye, about a Black girl that no one sees, that everyone thinks is ugly, and that her father rapes, and all through the book we do not really get her perspective. Years later, Morrison said she would write the book differently and give her a voice. Morrison spoke not just as a writer, of course, but also as a Black woman, so I ask Galgut if, as a white man, his conviction about keeping Salome as a “loud absence” might change in years to come.

“That’s a very interesting question,” he says, “but how can I answer you because how do I know what my thinking will be years from now? It’s always possible. I think those points on which one has a significant change of heart or change of mind are usually those where you feel enough self-doubt internally, too. You know, really experience a crisis of decision. And that was not the case with this point. I felt it out instinctively and I didn’t have a big internal debate with myself. It felt like the right choice.”

He told me that he was tempted to take a different route: keep Salome’s inner life withheld and, in the final pages, let it spill into the book. He decided that his ultimate choice was “a stronger way of making Salome’s presence felt.” It was, for him, “one of those moments where [the narrator] turns and faces the reader out of the page and says, ‘You know, if you didn’t know about this person, maybe it’s because you didn’t want to know, maybe you weren’t interested enough to ask.’”

He connects this to the broad question of literary satisfaction. “I mean, I know there’s a literary requirement, right? To provide a certain satisfaction to the reader. And, of course, I feel that myself, I feel the need to give something back to the reader who has invested a lot of time in this experience. But if what you’re conveying with your story is that the world is divided into good and bad people, that all problems are resolved, that every story is a circle reaching completion, that all is OK with the world—that feels forced to me and unlike what the real world is, what I see around me every day. So, for me, I guess there’s a kind of a balancing act; you’re trying to convey the incompleteness and the mixed morality of most humans who are not heroic or villainous most of the time. They’re a kind of a mixture of opportunism and self-interest and occasional flashes of altruism, but, you know, nothing is as clear as a hero or a villain. But if you want to convey that world, you run the risk of writing a messy, unresolved, incomplete book that just satisfies readers. So the balance for me is in trying to do both, to give an elegant experience that also feels incomplete, unresolved, and full of blank spaces in the same way the real world does. And in the real world, Salome, a person like Salome, still feels like a blank space. She’s someone I see all the time out there, but what presence, what voice, what agency does such a person have?”

It is from Salome’s son, Lucas, that due anger at his mother’s treatment comes. “Lucas is a voice that’s very audible right now in South Africa,” Galgut said to Irish Times. “In the years immediately after the transition in 1994, there was an almost deluded euphoria over all of us that we had now arrived somewhere totally different, and things were just going to be wonderful here on in. And of course, that was naive.”

He sees South Africa as similar, on a level, to Israel and Northern Ireland. He told Soft Punk Mag, “It’s one of those places where the history is so fraught that, in a way, it’s got a gravity that other places don’t have, and it holds you to it.” His country is “made of infinitely tiny but warring perspectives,” he has said. “There’s the sense always that whatever your narrative position might be, there are countless others coming in to tell you: ‘But what about this?’ and ‘No, you’re wrong about that.’”

His need to represent different views of that history is why he sets his novels in wide open, rural regions, rather than in the cities. There, his characters become symbolic, mouths of the country’s fragmented identities.

In late 2018, a young man named David Viviers, an M.A. in creative writing student at the University of Cape Town, emailed Galgut, asking him to supervise his thesis. Viviers had stumbled across The Beautiful Screaming of Pigs, and proceeded to the rest of his catalogue. “He explored the kind of territory I was interested in,” he wrote to me. “I knew I didn’t want my own novel to be driven predominately by action and plot. I felt there was something else guiding the events in Damon’s novels, something more subconscious and mysterious.”

Viviers told me that Galgut explores masculinity “as a type of failure.” His work, generally, “is often an exploration of failure: failure of masculinity, of communication, of language, of connection, of a country’s ideals, of promises.” But masculinity “becomes a frustration: a product, perhaps, of the violence and repressed anger inherent in white Afrikaans culture; something tied up with the fallacy of nationalism.” Sexuality in his work, Viviers said, “is more suggested than made explicit, something you feel between the words—a kind of mysterious electricity.”

Years before Galgut supervised Viviers, another M.A. candidate, the novelist David Cornwell, had asked to be his student. “In The Promise,” Cornwell said, “and especially Anton’s character, I do think Damon is doing some interesting stuff by aligning anxieties surrounding masculinity with the type of oppression that characterised white rule in South Africa.”

Lowry told me that Galgut’s insight into a certain masculine condition would have come from his own experience. “I suppose one can look at A Sinless Season as an entry point, where the backdrop is a boys’ boarding school. Damon himself was the ‘product’ of a traditional boys-only, privileged, colonial-style high school environment where masculinity would largely have been defined by sporting prowess and professional achievement, and ‘Old Boy’ networking was how you made your way up in the world. To move out of that lane, as it were, went against the grain and to do so visibly could be uncomfortable and problematic, and set you outside the fold.”

She has observed his full growth, having edited all of his books aside The Beautiful Screaming of Pigs. “Damon is a deep thinker and an astute observer,” she said. “As he matured over the years, he became more confident in allowing himself to experiment with the novel form and with different linguist styles and structurally interesting ways of constructing a story. This mixing of formats and trying out new things can be challenging for a readership wanting a more conventional lens, but always, with Damon, there is the beauty of a sentence, an image that startles, an idea preposterously explored that astonishes and astounds. A seemingly bland description with a meticulously placed comma can be as subversive and disruptive as a landmine.”

For Cornwell, the strength of Galgut’s writing is that can be appreciated on many levels. “What is so impressive is the combination of formal innovation and psychological acuity. Writers tend to excel in one—either they are stylistically interesting or they are uncommonly perceptive—but Damon consistently manages to be both.”

IV.

Some months ago, Galgut started reading a new book, Salvatore Satta’s The Day of Judgment, a novel that had lain untouched on his shelf for over 20 years. For all of his investment in writing as compulsion and therapy, his relationship with the idea of books as products is not predictable. In Artic Summer, his E.M. Forster tells Virginia Woolf, What earthly use are novels? How do they help anyone? In The Good Doctor, Frank says to Laurence about ideas generally, Do you really think talk and a few bright lights will save the world? Galgut does not believe that a book can change his life, or even anyone’s mind except through a cumulative evolution.

“You know, partly, it’s a reflection of books having lost their central position in the culture,” he tells me. “There was a time when books were very much at the centre of cultural life and thinking and, at that time, perhaps they had a power. That kind of power that we mean when we talk about changing the world. I mean, realistically, if you want to stir people emotionally, Twitter seems far more effective. Or, you know, TikTok. If the state wants to crack down, they wouldn’t crack down on books, they would crack down on Tik Tok or Instagram or something. I’m not meaning to denigrate the position of books in the world. Clearly, they are the most important thing that my particular world holds. Living in a world without books is absolutely unthinkable, unbearable to me. But individual books—do they change the world? No, I think it’s too big a claim.”

He has extended his pushback to certain social expectations of writers. “I mistrust the idea that a writer should be a moral signpost, just because most of the writers I know are not particularly moral people themselves,” he has said. “Because we’re all human. Even the best of us, with the most noble impulses, are always open to question.” None of his characters occupy such central moral space, either. “The world is much more open-ended and unresolved than, you know, the world of fiction makes you feel a lot of the time.”

Perhaps the only thing that is not open to his internal questioning is how he develops his books. “Most books, for me, begin in an unconscious way,” he explains. “They arise from buried impulses that you don’t fully understand. You just feel a certain voltage around particular ideas or images or something very basic and fundamental. The sense of a character in a certain situation, just some beginning, some little corner of something.”

Galgut disappears beneath the camera and rises with a big red register. It is the book in which he handwrote the first draft of The Promise. “They’re these registers that you can buy in India, which corner stores use for their receipts and doing, you know, their finances, and I really like them.” He shows me. “Yeah, I wrote here: ‘First draft.’” The dates: April 16, 2017 and July 31, 2019. The second draft: August 2019 and December 17, 2019. “I have quite a childish handwriting,” he chuckles.

There is something that he is reaching for but is still not sure he has attained: prose poetry. He said in the interview with Kona, about The Promise’s avoidance of his usual restraint, “The more you can lay down levels of language that pull against each other in different directions, the more the language speaks.” Sometimes this can only be resolved in tandem with the narrative voice. He has compared his prose in the book to painting techniques, “dabbing with a brush to give little points, like a kind of pointillism—it allowed me to fracture the image like Cubism would do.”

Viviers told me that Galgut “seems to write less with a pen and more with a scalpel.” There is “a metaphysical current that runs beneath his sentences, a sense of shifting shadows, a kind of nebulous haze.” He added, “You feel that there is an unconsciousness at play, something that hangs in limbo between sleep and wakefulness.”

Style, however, is not a problem that Galgut contends with until he has figured out the story itself. His method, in his first drafts, is to start out with much more than he will ultimately need. The point is to reason out the story, tie up loose threads, and explain things because that gives it shape and sense. Then the part he enjoys, in subsequent drafts: taking out information, slimming the story down so that it becomes more cryptic and there are no longer answers to every question.

His first drafts are “very much like lifting something up out of an invisible unconscious realm into the light, as it were. You’re trying to work consciously, of course, with a plan and an intention, but you are dragging up things that feel significant before you understand what the significance is. So, for me, the writing is a process by which you come to understand why you were drawn to these particular ideas of this particular story in the first place.” No matter what he does, though, he accepts that “books take on their own sort of voice and you sometimes have to fumble through it. The book cannot help but be an expression of whatever it is you’re wrestling.”

Perhaps this has been truest for him with Arctic Summer. He found that through Forster’s gayness, he was also interrogating his. He tells me that he is not sure that he ever managed to comfortably embrace the notion of being gay, even while speaking publicly about it several times. In a way, the public gestures themselves might have been him overcompensating for a lack of internal resolution.

“Maybe the novel did give a voice to certain aspects of my own self-dislike around being gay, and this feeling of not ever really being one hundred percent at ease with it,” he tells me. “I’ve never really thought about it, and I’ve never really given voice to that before. But yeah, I don’t know, it’s about being able to visualize yourself and see yourself on the cultural spectrum that’s opened up somehow.” Perhaps this was why, after the book came out, he told an interviewer, “There’s a certain mystery attached to why anybody writes books. And maybe it’s best left as a mystery.”

Now that the press rounds for The Promise are over, when he sits at his table these days, it is short stories that he works on, for a collection that might be his next book. He is now also back to feeling what he always feels after each book: that perhaps he has no other book in him. But he better understands his stimuli now. He knows that it takes him time, and that when it comes it will come from whatever is going on in his life at that time. The stories, for example, are about people away from home; but he no longer travels as much as he used to, so that could change. He knows, too, that his awareness of mortality is increasing, now that he has written a book about it. Perhaps even that next book will be about time. In The Good Doctor, he wrote, The past has only just happened. It’s not past yet. So time calls. On what scale, though? A historical novel about South Africa? It doesn’t feel like him, and he thinks there are writers who do it better, anyway. Plus that would mean research and he is not keen to go through again what he did for Arctic Summer. It really could be anything, though. But he will need to find it first. And when he does, he will need to find the right voice for it. ♦

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this piece described Roald Dalh’s “Pig” as being about a gay boy. The story is in fact about a vegetarian boy who is slaughtered and turned into meat.

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

More Essential, In-depth Stories in African Literature

— Cover Story, September 2021: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is in a Different Place Now

— Cover Story, July 2021: How Teju Cole Opened a New Path in African Literature

— Cover Story, January 2021: With Novels & Images, Maaza Mengiste Is Reframing Ethiopian History

— Cover Story, December 2020: How Tsitsi Dangarembga, with Her Trilogy of Zimbabwe, Overcame

— Nigerian Literature Needed Editors. Two Women Stepped in To Groom Them

— Mark Gevisser’s Long Mission of Queer Visibility

— How Lanaire Aderemi Adapted Women’s Resistance into Art

— TJ Benson Holds History and Hope

— A Novelist Entered Literary Curation, Still Honouring Her Feminist Roots

— Hannah Chukwu’s Call to Help Uplift Unheard Voices

13 Responses