Howard Meh-Buh Maximus first met Dzekashu MacViban five years ago, on a slow June evening in Yaounde, the capital of Cameroon. He was a new writer, in town for a workshop facilitated by MacViban as founding editor of Bakwa, a literary and arts magazine and the sole Anglophone publication in the mostly Francophone country.

Earlier in the year, their compatriot Imbolo Mbue, a previously unknown from Limbe who shot to literary fame in late 2014 after a $1 million advance for her debut manuscript, had published her novel, Behold the Dreamers, to acclaim. Following a working-class Cameroonian couple in New York City during the financial crisis of 2008, the book is a wider critique of the American Dream, what it means for hopeful immigrants, especially when African and Black.

In MacViban’s house, they discussed the novel and the African literary scene, the motivating publishing, the intriguing politics, the hilarious drama. MacViban told Maximus about Bakwa’s programmes for new writers.

“Even though I had never had that kind of conversation with anyone before, I knew it was the kind of conversation I wanted to keep having,” Maximus told Open Country Mag last November. “I like to tell people how Bakwa saved me from myself. It showed me the standard and refused to compromise.”

After the workshop, Maximus discarded the draft of the novel he was working on. He never told MacViban. Then he began a collection of stories centered around schools. Last year, his proposal for a novel won a Morland Scholarship, affording him £18,000 to develop a story of four friends in an a cappella choir, whose lives are upended by the Anglophone Crisis, the wave of violence—also known as the Ambazonian Conflict—that has swept Cameroon’s English-speaking regions for over four years now.

Maximus, now a staff writer at Bakwa, is a prominent member of a new generation of Cameroonian writers producing work in the shadow of the Anglophone Crisis, writing through and around it, and foregrounding the million other elements of life in a multicultural, multilingual country. They include Nana Nkweti, a Caine Prize finalist and Iowa Writers’ Workshop alumna whose debut story collection, Walking on Cowrie Shells, a mix of realism, mystery, and horror, came out this month; Clementine Ewokolo Burnley, a finalist for the Amsterdam Open Book Prize and the Bristol Short Story Prize; Bengono Essola Edouard, winner of the Bakwa Short Story Competition; and Nkiacha Atemnkeng, a former airport official-turned-writer who won a Sylt Foundation Writing Residency and is now studying for an MFA at Texas State University. Many of them were brought together by Bakwa, which has introduced them to a larger audience far beyond the borders of Cameroon.

Caught up in National Crisis

MacViban started his curatorial work at Bakwa in order to fill a gap in culture. He launched it in 2011, after Cameroon’s then only Anglophone culture and politics publication Pala Pala closed down. He was 25 then, a post-graduate student at the University of Yaounde. Most of the new writers gathered around the magazine were influenced by their Cameroonian forbears, notably the novelists Ferdinand Oyono, Mongo Beti, Francis Bebey, Mbella Sone Dipoko, Kenjo Jumba, and Linus T Asong; others had moved from the African Writers Series to contemporary writers.

To assist their growth, Bakwa started fiction and creative nonfiction contests, fiction and translation workshops, a reading series, and a podcast. By 2016, MacViban had the idea to hold physical events in the major cities—Yaounde, Douala, Buea, Limbe—which led to cross-lingual networks of Anglo- and Francophone writers.

That year and the one after, the most read piece on Bakwa’s website was a 4,000-word analysis titled “What is the Anglophone Problem?,” by the writer Harry Acha. It traces the peculiar situation of Cameroon’s English-speaking population in its northwestern and southwestern regions, seized from Germany by Britain after World War I, christened Southern Cameroons and administered as part of Nigeria until the referendum of 1961, when it became part of Cameroon. From the gradual name changes—the Federal Republic of Cameroon in 1961 to the United Republic of Cameroon in 1972 to the Republic of Cameroun today—to the return of multiparty politics in 1990, to the controversial constitution amendment of 2008, it outlines a political and cultural erasure in progress, a Francophonization enacted by Paul Biya, the country’s president for 39 years now.

Writing on the Anglophone Problem was not new. It was a subject of John Nkemngong Nkengasong’s 2004 novel Across the Mongolo as well as work by Bate Besong. But the violence that started in 2016 was the worst so far: hundreds of communities destroyed, thousands of people dead, half a million displaced. In The Guardian, Imbolo Mbue used an essay on hair to reflect on the crisis. Later, Nigeria’s Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie brought more attention to it in The New York Times.

For security reasons, Bakwa stopped physical activities in the Anglophone regions. “How does one begin to describe the trauma and insecurity of working when one knows that their family, friends and loved ones are permanently at risk?” MacViban said. His father, Mwalimu Johnnie MacViban, had been imprisoned for five months in 1986, alongside two other journalists, for airing a radio story on multi-party politics.

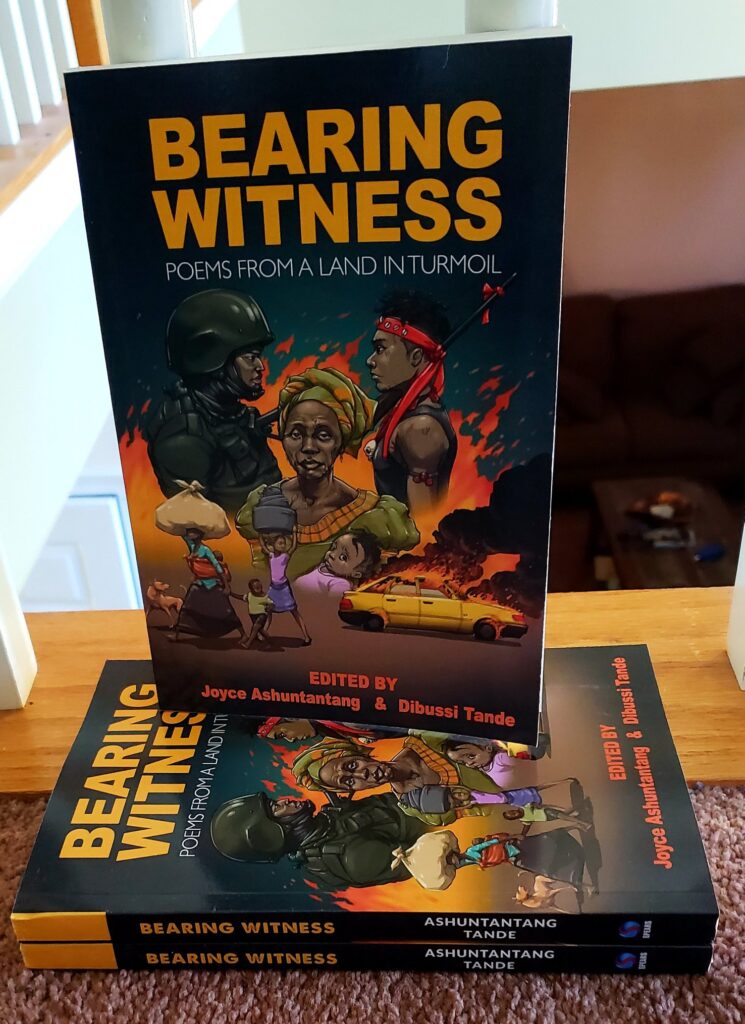

For the new generation of writers, it was their dominant question. In late 2017, Dibussi Tande, a Chicago-based poet, editor, and political scientist, and Joyce Ashuntantang, a poet and professor of English at the University of Hartford, noticed that, on social media, many writers were sharing poems and eyewitness accounts. They had co-edited an anthology in honour of Besong, and, in 2019, they announced a series called Bearing Witness, comprising volumes of poetry, fiction, creative nonfiction, and art responding to the Crisis. The first, Bearing Witness: Poems from a Land in Turmoil, published last June, included 150 poems from 73 established and emerging writers. The series, “a guidepost to collective memory,” is meant to raise money for people affected by the Crisis.

There have also been Francophone anthologies responding to the Crisis: 2019’s Cendres et Mémoires (Ashes and Memories), co-edited by Raoul Djimeli, Timba Bema, and MD Mbutoh, and 2020’s Cadavres de l’unité (Corpses of Unity), co-edited by Nsah Mala and Mbizo Chirasha.

“It would have been surprising to see new writing from Cameroon remaining silent in the face of the crisis,” said Nelson Kamkuimo, a poet and short story writer in French and English who contributed to Bearing Witness.

Monique Kwachou, a Caine Prize Workshop alumna and post-doctoral feminist researcher, shared that it was in writing op-eds and think pieces on the Crisis that she “found my writing voice.” “There is a great deal of academic writing also responding,” she said.

“These days, even when I write about unrelated themes, I generally find myself recontextualizing them within the crisis, especially in my essays,” Nkiacha Atemnkeng said. “It’s like we now walk, sleep, and dream the Anglophone Crisis.”

Diversifying Stories

Writing national tragedies sometimes raises broader artistic and cultural questions. At a reading at the University of Lagos, during Bakwa’s literary exchange programme with Nigeria’s Saraba magazine in 2017, an academic asked the panel of Cameroonian writers why they weren’t also writing about their country’s Bakassi conflict with Nigeria.

“Historically, much of Cameroonian writing has been protest writing,” MacViban told Open Country Mag. “Inasmuch as writing isn’t created in a vacuum, writers are free to interpret and document their times in ways that feel truest to them, write about what they want and how they want; thus new writing shouldn’t only respond to crisis.”

There is variety in Limbe to Lagos: Nonfiction from Cameroon and Nigeria (2019), the resultant anthology from the exchange, but, on the Anglophone Crisis, MacViban noted that there has been “more poetry, nonfiction, and opinion pieces than fiction and drama.”

Atemnkeng is also wary of sameness. “The danger is that we may be tempted to make the crisis our single story for as long as it lasts,” he said. “I advocate for us to write about it. But I believe that we should write about other themes as well.”

Ethnically, language questions ripple across the country. Many Bamilekes and Bassas, for example—ethnicities from primarily the Francophone region—were born, raised, educated, and now work in the Anglophone system. “Imagine a story that captures their feelings in such a liminal space,” Atemnkeng said. “I’ve got distant paternal family members in Dschang, in the French-speaking region. Since they cannot speak English with us, the means of communication is our local language, Nweh, and their local language, which is similar. The speaking beats become much slower and louder. There are remarkable cultural differences between both families, so much complexity. Now think about all that in a book. Baam!”

Thematic diversity is a lure. For years, Atemnkeng worked on an aviation novel, based on humourous encounters during his time at the Douala Airport. He is also thinking of a football novel. “Wouldn’t it be fascinating to read about Roger Milla and Samuel Eto’o? Or a reimagination of the events surrounding our 1990 World Cup exploits? Or perhaps a Makossa novel, too.”

Nana Nkweti, already deviated from the realist tradition, has said that she is currently writing “an intergalactic bildungsroman,” involving interstellar slave ships, quarantine, and rap. In the novella, the “alien dialect” is Bamileke, her mother’s ethnicity.

A Scene in Bloom

Last December, the Cameroonian Francophone novelist Djaili Amadou Amal won France’s Prix Goncourt des Lycéens, in the prize’s 33rd year, for her novel Les Impatientes. The 46-year-old Fulani Muslim feminist activist is part of an older generation experiencing an arrival of sorts in the last few years, in both the French- and English-language publishing industries.

Hemley Boum, a two-time winner of the Grand prix littéraire d’Afrique noire, last year won the Amadou Kourouma Prize, awarded previously to Max Lobe. Leonora Miano also won the Prix Goncourt des Lycéens and the Grand prix littéraire d’Afrique noire. In 2019, Eric Ngalle Charles, who fled Cameroon after being imprisoned for supporting an Anglophone movement, was selected, for the National Centre for Writing, as one of the UK’s notable BAME (Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic) writers.

Patrice Nganang, a Professor of Comparative Literature at Stony Brook University, has recently been praised for the translated novels Mount Pleasant and When the Plums Are Ripe, the first two volumes in his World War II trilogy. A critic of President Biya, he was abducted at an airport in 2017, and a year later published La Revolte Anglophone, Essais de Liberte, de Prison et d’Exile’ (The Anglophone Revolt: Essay of Liberty, Prison and Exile), about the crisis and his time in prison, the proceeds of which supported refugees and political detainees.

Meanwhile, Mbue’s second novel How Beautiful We Were, set in an imaginary village where environmental degradation sets off a revolt against an oil company, has been well received.

Ashuntantang, whose poetry collection Beautiful Fire won the 2020 African Literature Association (ALA) Book of the Year Award for Creative Writing, told Open Country Mag that, beyond diasporic writers, “there are well-established Cameroon-based writers who have written excellent literary texts, but who are relatively not well-known outside Cameroon, like Babila Mutia, John Nkemngong Nkengasong, John Ngong Kum, Janet Ekane, Alobwede D’Epie, and Nol Alembong.”

It was Mbue’s Behold the Dreamers, Ashuntantang said, that “put Cameroonian literature squarely on the global stage.” The novel, a favourite of book clubs and a selection for Oprah’s, has been translated into 11 languages and is on university reading lists. “The story is a celebration of Cameroonian resilience,” she said. “The hope is that it opens up doors for other talented but largely unknown Cameroonian writers who would otherwise not get a second look from agents and publishers.”

If Cameroonian literature is to keep pace, Kamkuimo believes that Bakwa will have a role to play. The magazine, he said, is “the leading light, a nursery, a reference.”

Bakwa’s contribution, “though largely unheralded, has been revolutionary,” Ashuntantang said. “It brought Cameroon’s voice into African literary spaces in ways that were hitherto absent. Cameroon, especially Anglophone Cameroon, had been absent from some of the major corridors of creative writing in Africa either as curators or literary entrepreneurs. Bakwa changed that. It has ensured that a Cameroon-led magazine is in the marketplace of literary ideas.”

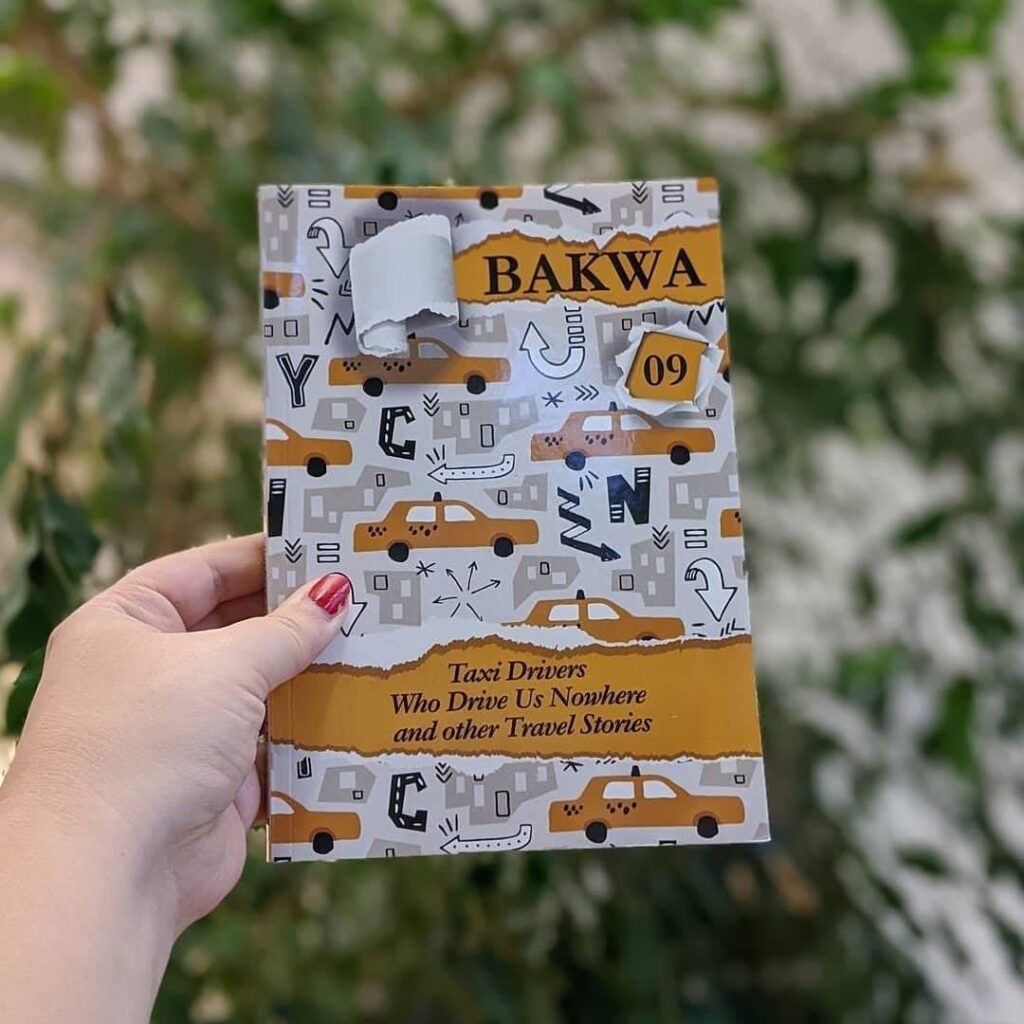

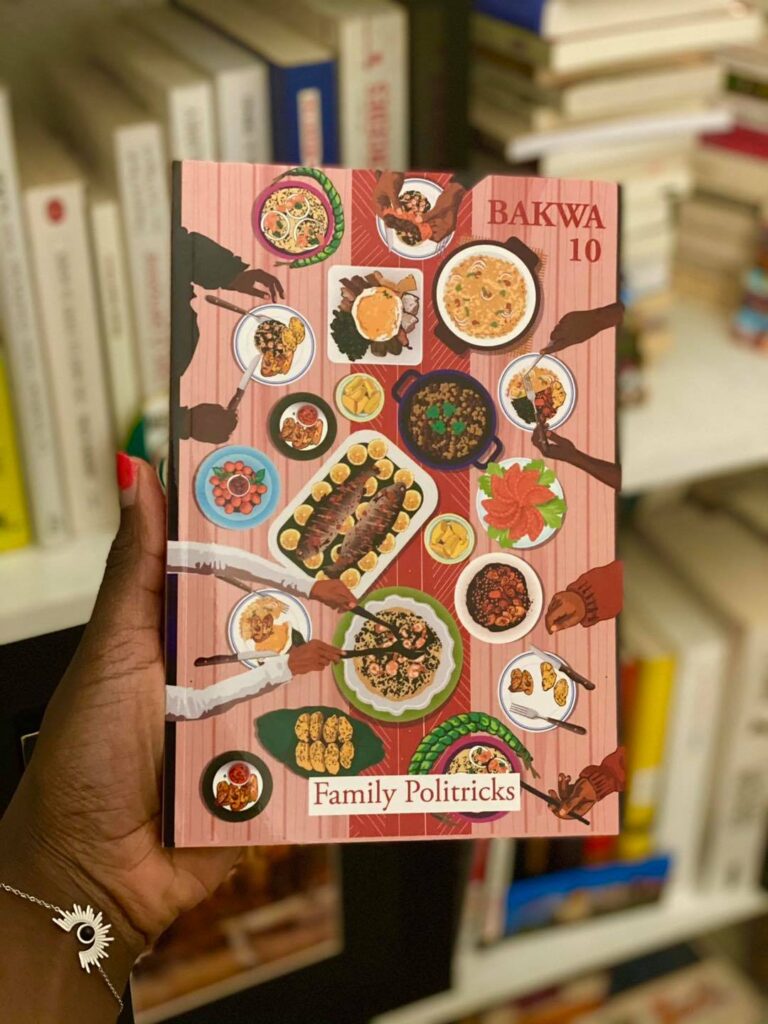

In 2017, Bakwa launched a social media campaign, “100 Days of Cameroonian Literature,” sharing a book per day. In 2019, MacViban set up a publishing arm, Bakwa Books, which has released a slew of books: anthologies Of Passion and Ink: New Voices from Cameroon and Your Feet Will Lead You Where Your Heart Is, magazine issues Bakwa 09: Taxi Drivers Who Drive Us Nowhere and Other Travel Stories and Bakwa 10: Family Politricks, and Johnnie MacViban’s novel Twilight of Crooks. Last year, the first Bakwa Literary Festival was held on Instagram Live. This year, the magazine will celebrate its 10th anniversary.

“Gone are the days,” Ashuntantang said, “when the literary critic Steve Arnold explained that ‘In spite of its existence, Anglophone Cameroon writing was conscious of itself only in fragments, having been isolated from the mainstream literature on the continent, and even within its own national boundaries by Cameroon’s unique historical circumstances.’ This literature is now in conversation with mainstream African literature and this trend will continue thanks in part to a new generation of young writers who are harnessing the power of digital media, and to publishing houses such as Spears Books, Bakwa Books, and Langa’a publishers.” Her hope is for Cameroonian literature to enter “the contested but celebrated Western-induced canon of African literature.”

Louisa Lum, a poet and fiction writer who came up seeing only two female Cameroonian authors in Calixthe Beyala and Margaret Afuh, said that Bakwa is a “motivational factor” in the novel she is working on, “a psychological journey of self-discovery” set against the backdrop of the Anglophone Crisis. “I believe that Cameroon literature is coming of age and will soon be competing efficiently with its Nigerian and Southern African counterparts,” she said.

But not everyone sees the literary bloom as new. “I don’t really think we’re having a literary renaissance at the moment,” Atemnkeng said. “Cameroon has always been eternally present on the literary map, both in French and English, which I think is a pretty unique contribution to African literature. Mongo Beti published three critically acclaimed novels in France before Achebe even published Things Fall Apart.”

He notes that writers from the French-speaking region of the country achieved success first. A few, like Guillaume Oyono-Mbia, achieved success in both French and English. “Sankie Maimo was the first Anglophone writer to publish a play, in Ibadan in 1959, and more have followed: Mbella Sonne Dipoko, Linus T Asong, Bate Bessong, Bole Butake.”

Rather than a “renaissance,” Atemnkeng argues that “what is happening now is that there is a new wave of emerging and mid-career writers from the English-speaking region who are getting acclaim that their predecessors didn’t achieve.” He pointed out that since the publication of Limbe to Lagos, five of its 10 contributors have gotten into MFA programmes in the U.S. and the U.K.

“Talented young writers are getting the recognition they deserve, writing books that are urgent, playful, and experimental, winning awards and getting good agents,” MacViban said. “I see Cameroonians reading more home-based writers, I see more translations across the official languages and local languages. There are already signs that the future we dreamed of is here.”

For Maximus, deep into his novel of four choir friends, the opportunities should be capitalized on. “I can only hope that more Cameroonians actually take out time to work on their craft and not dismiss it as a pipe dream,” he said. “Young Cameroonian writers, I think, are beginning to take up space.”

More Big Stories from Open Country Mag

— How Tsitsi Dangarembga, with Her Trilogy of Zimbabwe, Overcame

— With Novels & Images, Maaza Mengiste Is Reframing Ethiopian History

— Nigerian Literature Needed Editors. Two Women Stepped in To Groom Them

— Mark Gevisser’s Long Mission of Queer Visibility

— How Lanaire Aderemi Adapted Women’s Resistance into Art

— TJ Benson Holds History and Hope

— Hannah Chukwu’s Call to Help Uplift Unheard Voices

6 Responses

Nice coming across such great indigenous writers.

My names is Koffi Mafany Teke, an aspirant teenage writer having two unpublished memos which I think will be of great importance to the literal and entertainment community.

I wish and hope to work with you guys.

As a Cameroonian writer currently editing the first draft of my non-fiction book, it is heart-warming to read about my fellow Cameroonian writers that are fighting to change the narrative and bring light to the dire situation of the country caused by the Anglophone crisis.

Thank you for this wonderful piece.

I will love to connect with these writers.

Interesting read. This is a good step forward that will eventually get Cameroon literature and especially Cameroon Anglophone literature onto the world stage