Khadija Abdalla Bajaber first discovered literature in the classroom. It was not a favourite of hers because she did not like all the books taught. Years passed before she found an appreciation for it, in the library of her school. She was not a very sociable child and so the library was her sanctuary. Later, in an effort to enter editing, she studied journalism at the United States International University Africa (USIU), Nairobi, an endeavor she said was half-hearted.

The time after university was frustrating. With her stack of incomplete projects, she gave up on prose-writing, resolved to write only poetry, which she found consistent. But what she was producing lacked heart. She felt like she had hit a dead-end and she was angry with herself.

Then she read Deathless, an alternate historical novel by the Russian writer Catherynne M. Valente, and was intrigued, because she did not expect to find it so suited to her taste and yet so distinctively Russian. It got her thinking about writing something imbued with her own culture.

“I think a lot of the work I’d been doing up till that point didn’t really take advantage of the rich nuances I already had in my own culture,” she said. “I thought, why am I not using this? Why am I not talking about this more? I needed to write something that doesn’t shy away from my identity and my culture.”

There were things she questioned about Mombasa, the city of her birth on the southeast coast of Kenya, and she needed to re-approach her relationship with it, to understand her place in it. A coming-of-age tale steeped in mythology followed.

The House of Rust is the story of a young Hadrami girl Aisha, who embarks on a search for her father, a fisherman lost at sea. Accompanied by a talking cat, she sets out on a boat made of fish skeleton. She survives sea monsters and rescues her father, but returns home to a life changed forever. The novel explores Mombasa in specifics but is also a broader take on identity, belonging, and independence.

When Bajaber first started it, the first chapter came together so well that she almost did not continue writing. She had written fiction before, all unfinished like her other prose pieces, so the new ease threatened her commitment. But one night, during one of the many power cuts in Mombasa, her mother asked her for a story. In a sitting, she spun one with her first chapter as its beginning, making it up as she went. The rest of the story flooded in.

If it wasn’t for that moment, she said, if it wasn’t for her family gathered in that dark, hot living room, she probably would not have completed the book.

Although she always knew she wanted to write a Mombasanese fairytale, she wrote Aisha to be different from the heroines of fairytales she had heard and read growing up. Aisha is “ugly,” awkward and strange, strong-willed but fallible. Bajaber does not even think of the character as a heroine. “This idea of a hero is an idea of this grandness,” she said, “when sometimes the journey is a very private one.”

She wrote her thinking of how tough and confusing being a young girl had been for her, but she makes it clear: she is not Aisha and does not identify with her struggles.

In the rest of Kenya, Mombasa has a reputation for, among other things, witchcraft and voodoo. Bajaber believes in the capacity of the supernatural but it does not spook her. She understands that there should be decorum when it comes to the supernatural. “As long as you are not rude, or being ungrateful or mean, then why would you fear? I had to approach those interactions with a kind of care and empathy.”

She wields fantasy to convey how Mombasa can remember and acknowledge its roots. Through the monsters in her novel, she peers into the past, into a history of prosperity. She thinks of one character, the snake prince Almassi, as the spirit of the city.

“He has forced himself to be a slave,” she said of Almassi. “He has pretended he doesn’t know. He has pretended he is not strong. He has allowed people to think he has forgotten his teeth.”

Because she didn’t learn about Mombasa’s history in school, she could only hint at this lost time. She grieves that she may never fully know these things. But since The House of Rust came out, other writers and curators of Swahili and Hadrami cultures have reached out, and she is grateful to have been exposed to more information.

While still a manuscript, in 2018, The House of Rust won the inaugural Graywolf Press Africa Prize, which came with a $12,000 advance fee. Judge A. Igoni Barrett called it a “heroic first novel” that “has struck deep into that mythic realm explored by everyone from Homer to Hemingway.” He wrote:

Everything in this story sparkles: the fierceness of the narrative voice, the unimpeachable dramatic timing, the sumptuous imagery, the insightful characterization, the spirited wordplay, the honed wisdom of the dialogue, the bold imagination. Everywhere in this story is evidence of a mind that understands that we read not only to see other worlds or lives, but to feel them.

Bajaber is delighted that a younger generation of African writers has become more prominent and published. She likes the idea of wider, global recognition, but she is most pleased seeing Kenyans reading Kenyans. She only began reading contemporary Kenyan literature a few years ago, and she is mostly acquainted with short stories, a form she associates with much skill.

There is an “innate Kenyanness” in the works of her contemporaries, she said, naming Makena Onjerika, Troy Onyango, and Linda Musita, among others. “Kenyanness is not Nairobiness or Mombasaness,” she added. It is hard to describe but she makes an attempt. “It is an attitude, it is language, it is the way information is structured in a sentence, it is the exclamations.”

And yet, she said, each writer is distinct. “I can never read a Kenyan writer and think they sound like another Kenyan writer. Kenyan writing is very charismatic. It marches to the beat of its own drum.”

It is her understanding of the Kenyan psyche, the bravado, a tongue-in-cheekness and skepticism, a quality that is grim but also funny. “We all kind of understand that we are living in a certain time where people are on the verge of defeat. But the hope for the future lies in themselves, in the young people and the thinkers. We’re not looking anywhere else. And it bleeds into the writing.” ♦

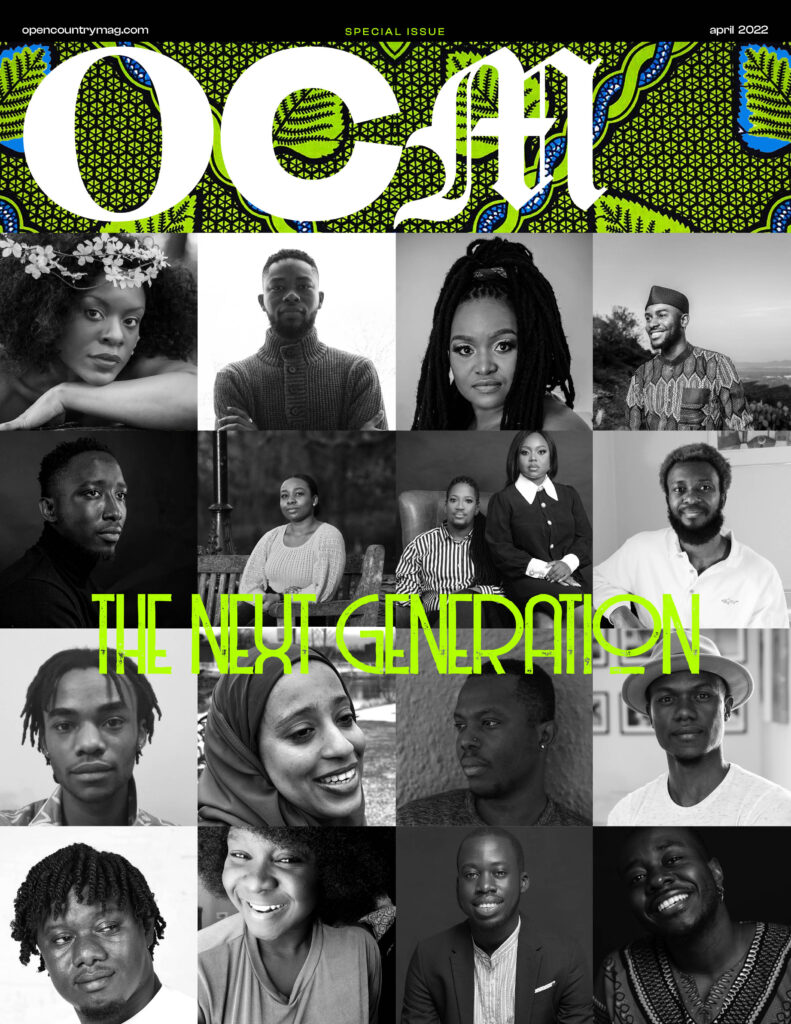

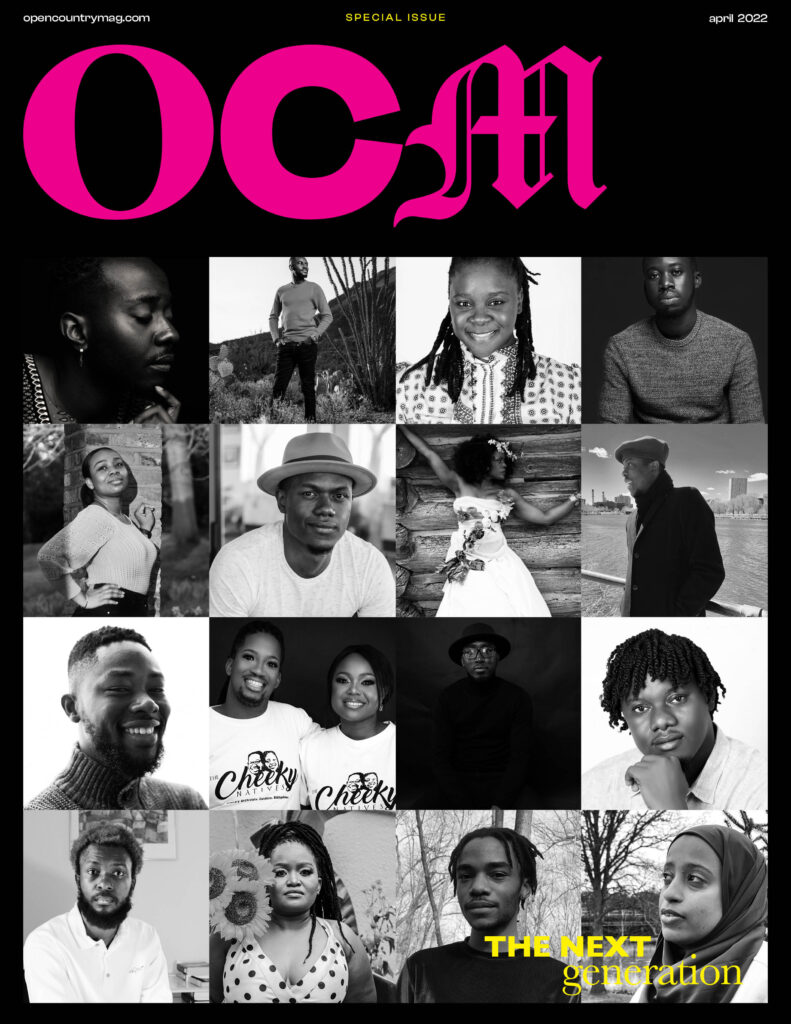

“Khadija Abdalla Bajaber on Fantasy and the Character of Kenyan Writing” appears in The Next Generation special issue of Open Country Mag, profiling 16 writers and curators who have influenced African literary culture in the last five years, curated and edited by Otosirieze Obi-Young. The issue comes with two covers.