Makena Onjerika won the Caine Prize in 2018 for her short story “Fanta Blackcurrant,” about street children. The fourth Kenyan to receive the award, she made news when she donated a tenth of her £10,000 prize money to street children in Nairobi.

A graduate of Economics from Amherst College, she earned her MFA in creative writing from New York University. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Johannesburg Review of Books, Adroit Journal, Fireside Quarterly, Wasafiri, Waxwing, Jalada, New Daughters of Africa, Doek!, and DRR. Last year, her short story “Girl Games” appeared in Granta and she was shortlisted for the 2020 Bristol Prize.

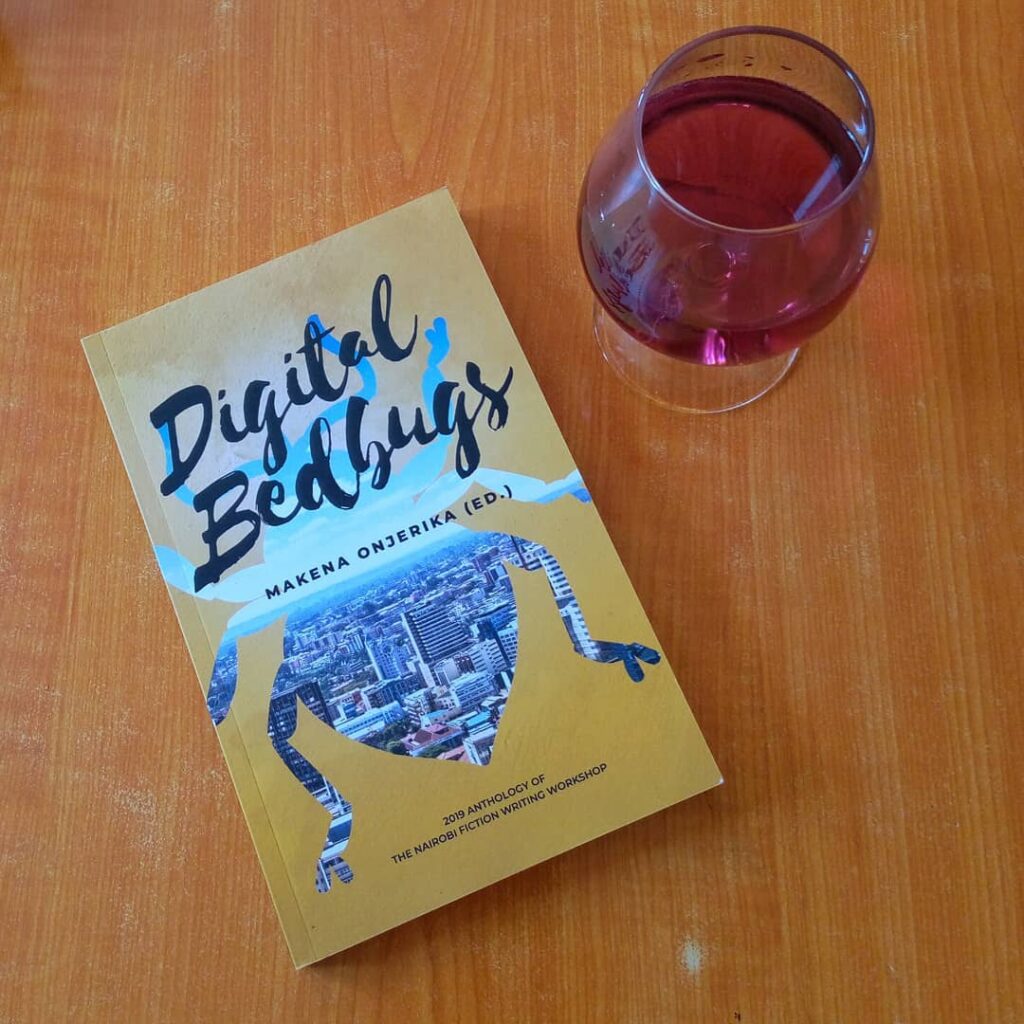

After returning to Nairobi, Onjerika started the Nairobi Writing Academy to teach the craft. The workshop has produced two anthologies, Digital Bedbugs (2019) and Equipoise (2020).

She spoke to Open Country Mag about her plans for the academy.

Could you tell us a little about the Nairobi Writing Academy and what inspired it?

The Nairobi Writing Academy started out as the Nairobi Fiction Writing Academy. I started it to share my writing knowledge with Kenyan writers and to make an income to support my writing. We have many writers in Kenya, but production is significantly lower here as compared to say Nigeria. I wanted to build a structure and community that would catalyze more writing, more publishing, more unearthing and telling of Kenyan stories. Writers from all over the continent and the diaspora started writing to ask how they could join.

When COVID-19 came along, I moved the classes I was teaching then online via Zoom and realized that this would allow me to teach writers outside of Nairobi. When request came in for classes other than short fiction, it made sense to start collaborating with other African writers to offer classes outside my area of interest. Many writers in the USA and Europe support their writing careers by teaching. We publish an annual fiction anthology now. See Digital Bedbugs and Equipoise, our 2019 and 2020 anthologies, on Amazon.

There are those of the opinion that writing cannot be taught. As an MFA graduate and teacher yourself, what do you say to this? And to what extent has being taught influenced your work?

In the words of Francine Prose, you cannot teach anyone a love of words or an interest in story or that interesting manner of seeing the world that engages people, or the ability to weave disparate things together creatively. In this sense, writing cannot be taught. It’s a natural talent. But all writers need to hone their skills and understand technique, that is, the craft of writing. This is what I learnt in my writing classes and what I teach.

The best writers taught themselves by writing and also my reading, and not just reading, but reading with eyes wide open. The writing class is really a class in which participants learn how to see what other writers are doing and how to emulate them. I need the classes myself. I would never have seen the things I see now in fiction without them. I am not that clever. I still read craft books and especially love essays that focus on how fiction works.

What mistakes do aspiring writers often make? What do you think is most important they learn? What do you hope they take out of the classes?

Aspiring writers often mistake first drafts for stories. Nabokov said we do not read books, we re-read them. In the same manner, we do not write stories, we re-write them, many times over. It’s not a story until you have beaten it to death, and it’s survived.

Also, aspiring writers do not realize just how much reading is involved in writing. To write one good short story, read 500 good short stories. If you are not reading, you probably think you are writing mind-blowing stuff someone else wrote 50 years ago.

How has teaching writing impacted you as a writer?

It keeps me reading and exploring technique. And it has given me a wonderful community of like-minded individuals here in Nairobi who are quite fun.

What texts have you recommended the most in the classes? Which do you admire the most?

We read 40-plus authors in my short story class. If I were to suggest one text, it would be the craft book Reading Like a Writer by Francine Prose.

Creative Writing is hardly recognized in universities in Africa; aspiring writers often have to thrive solely on community and informal spaces. What effect do you think this has had on the literary scene in Africa?

It’s marginalized writing and locked out many would-be writers from the work. Each African country is a conglomeration of hundreds, thousands of experiences, backgrounds, beliefs, etc. We need stories from every angle, and we won’t get them if only a select few are writing.

What are the challenges you’ve faced running the academy?

At present, reaching writers in all African countries. Social media helps, but I would like the Academy to be better known than it is.

What are your future plans for the academy?

More classes by more African writers.

I am particularly keen on novel-generation and novel-editing classes. I would love to be able to offer sci-fi and fantasy writing classes. Classes in all the genres and special topics classes that focus deeply on specific writing elements.

The Academy is also in the process of building an endowment to fund annual writing prizes across genres. We will venture into publishing and distribution and eventually build a writing retreat center in the Kenyan countryside or coast.

Could you tell us what you are presently working on?

A novel in short stories, a novel on contemporary Nairobi life and a fantasy novel.