As a child, Remy Ngamije got low scores in writing tests at school—5/10s, 1/5s. On the margins of his notebooks, his teachers scribbled in red: Remy does not have an imagination. “It’s not that I had no imagination,” he said on our Zoom call in late November, “it’s just that I was poor.” He was six then and still learning English. His lower middleclass family had just moved to Namibia from Kenya, where they had moved to from Rwanda, where he was born.

“There was a very big pressure on my siblings and I to learn this language,” he recalled, “to write as well as we could in it, to gain a foothold in our education, which was always being disrupted with movement. I figured out that this thing could be used not only to express yourself, it could also be used to defend yourself. Being bullied was a linguistic thing for us, but as soon as you could speak this language and you could defend yourself, then you could diss somebody, you could talk back on the playfield.”

His parents took him and his siblings to the public library on Saturday mornings and picked them in the afternoons. With learning came leisure and with leisure curiosity.

In second grade, his teachers asked for more assignments, mostly essays on how the pupils spent their weekends. Ngamije had nothing new to add to previous essays: his weekends were the same because his family, like most poor families, did nothing exciting—he cleaned the house, went grocery shopping with his dad or mom, went to the library. His essays were repetitive, so his teacher wrote: Remy needs to cultivate an imagination. Being competitive, he felt discouraged. He was improving his writing but his teachers were searching for storytelling.

One weekend, he decided to lie in his essay, and began writing things he did not do, things his family lacked money to do. He was shocked when his teacher scored him 9/10. Later, he convinced himself that he wasn’t lying: the essays were creative expression and he had just discovered how to exercise it. As the years passed, he took that moment as when his attitude changed, and he applied it in his understanding of literature.

“It’s less about the question that’s being asked, it’s about the one that’s not being asked,” he told me. “They were asking us to write about a weekend but it was more like, ‘What did you dream about?’ And little by little you start learning how to document your life. You start learning about what you think about your opinions, about your fears. You basically learn self. Creating some internal world for yourself and sharing that with somebody.”

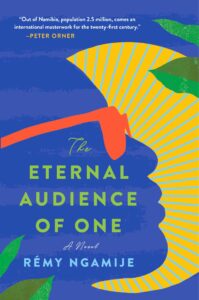

Ngamije gained notability in the literary scene in 2019, with his debut novel The Eternal Audience of One, which traverses countries and cities: Rwanda, Paris, Brussels, Nairobi, Cape Town, Windhoek; narrated by a young man with a quirky way of looking and a strange way of relating to things. The book was compared to Zadie Smith and Michael Chabon. A review in The Johannesburg Review of Books called it “a brilliant postmodern take on how the arts—writing and music in particular—can deliver a troubled mind into gathering and holding all that our senses, by experience, have transmuted into consciousness, which, in a nutshell, is the greater purpose of our lives in this world.”

In the two years since, Ngamije won the Commonwealth Short Story Prize and was shortlisted for the AKO Caine Prize, twice, and for the Morland Scholarship. In these two years, no new African writer has had such a wide embrace—from every prize they were eligible for.

The Eternal Audience of One was motivated by his tumultuous time at the University of Cape Town, where he was a Construction Studies freshman, hoping to transfer to Civil Engineering, but always thinking about writing. It was 2007 and he had just come to South Africa. He had experiences with friends that felt cinematic. “Like I was watching this story,” he recalled, “and I’d always hear this narration happening. Racism at clubs happen and it would feel so like a scripted thing.”

He wrote them down: scraps of dialogue, thoughts, dreams. It floated in his head like bullet points. But even after he finally changed programmes to English, and took a creative writing course in his third year, he couldn’t write yet because he went off to Law School. Later, he worked in advertising, and while teaching English in high school, he found time for his built-up frustration. “One day I literally sat down, I said screw it, I’m going to write this novel,” and he began, in 2016, nine years after he had the idea. Blackbird Books published The Eternal Audience of One in South Africa, and, last year, Scott Press released it in the UK.

On the continent, Namibian literature is relatively new on the map, lacking the recognizable traditions of countries like Nigeria, South Africa, Egypt, Kenya, and Zimbabwe. It was, for example, only 21 years ago, in 2001, that Heinemann’s African Writers Series picked its first and so far only novel from Namibia—Neshani Andreas’ The Purple Violet of Oshaantu, which also came out that year.

Growing up, Ngamije knew this, and even after his book came out, he said, he continued to feel like an outsider, “outside the current, because of geography.” In the Namibian capital Windhoek, he had been part of an informal writing group started by an American Fullbright Fellow Peter Orner, and the group continued after Orner left. It was there that he met Mutaleni Nadimi. When his book came out, the two decided to start a literary magazine to “keep the momentum going.”

Doek! launched in 2019, hosting meetings of writers in Windhoek because they had no idea how to solicit work. With the pandemic, they opened the platform to all Namibian writers. The publication became formalized, an editorial team was formed, and a direction set.

“I learned very, very quickly,” he said. “I spent a lot of time just researching what other magazines on the continent are doing, following them, learning from them and steering, you know. We are involved in the grass roots of creating this traditional, or rather rediscovering our, role—our literary tradition here in Namibia, and then bring it to the world.”

Doek! has published over 100 writers, including 30 from Namibia, across six issues. Its seventh issue, last November, had for the first time all of its fiction by Namibians. Last year, also, a story it published, Troy Onyango’s “This Little Light of Mine,” was shortlisted for the AKO Caine Prize. Ngamije’s own story, “The Neighbourhood Watch,” was also shortlisted. His story appeared in Lolwe, edited by Onyango. The crossover recognition created publicity for the work going on at both magazines. A New York Times feature followed, raising their profiles. Doek! partnered with Bank Windhoek to run the Windhoek Doek Awards, the first in Namibian literature. This month, it will hold its first festival, in partnership with the University of East Anglia’s International Chair of Creative Writing Tsitsi Dangarembga, who will also headline it.

Part of Doek!’s mission, Ngamije said, is “finding voices from the continent that are also in lesser heard traditions and joining together to amplify each other’s work. We will go to, like, Malawi or we’ll find someone from Cape Verde. I’m really interested in these lesser-known traditions because I feel more akin to them.”

He is concerned about the lack of cross border engagement. “South Africans are very good at promoting their own literature. But when you ask them, for example, what is happening in Eswatini, what is happening in Namibia, what is happening in Zambia? Zimbabweans are well known for producing work, but when you ask them what’s happening in Botswana, Mozambique? When you ask Southern Africa as a region what is happening in Madagascar? I live in excitement for the day we’re able to open our doors for the rest of the continent to participate on an equal footing.”

Doek! functions as an arm of a same-name arts organisation, which he chairs. “My drive is, these things are existing out there, how do we get them to work for other people? How do we find a rhythm and the pace of creation? If you get away from literature and you think about it as a business, solutions show up very, very quickly. On the board of trustees, all writers will do is speak into abstraction, whereas bankers, bankers will tell you what is the value of this thing. What is the profit and loss? What is the outcome of this project? Has it fulfilled its goals? That’s how Doek! has been able to take a lot of the steps that it has, because I think like a writer, but my trustees are not writers. They ask me questions that have to do with tax questions, that have to do with bank charges, finance questions that have to do with longevity, stability, sustainability. Like, if you start this, is it like a one-off project or is this a structure that you will be able to replicate in two years?”

In Windhoek, Ngamije runs a salsa club. He sees his literary steps as “a series of very fortunate coincidences that I could not have prepared for, that I did not aim for from the outset.”

He told me, “I’m still very new to this and I’m still learning a lot and it’s shocking how much I do not know at all and so, yeah, that’s why I still feel like I’m outside. And I like that space because it allows for experimentation. It allows space for curiosity, space for adventure, and then it also allows me to step out of that space and say, ‘Look.’” ♦

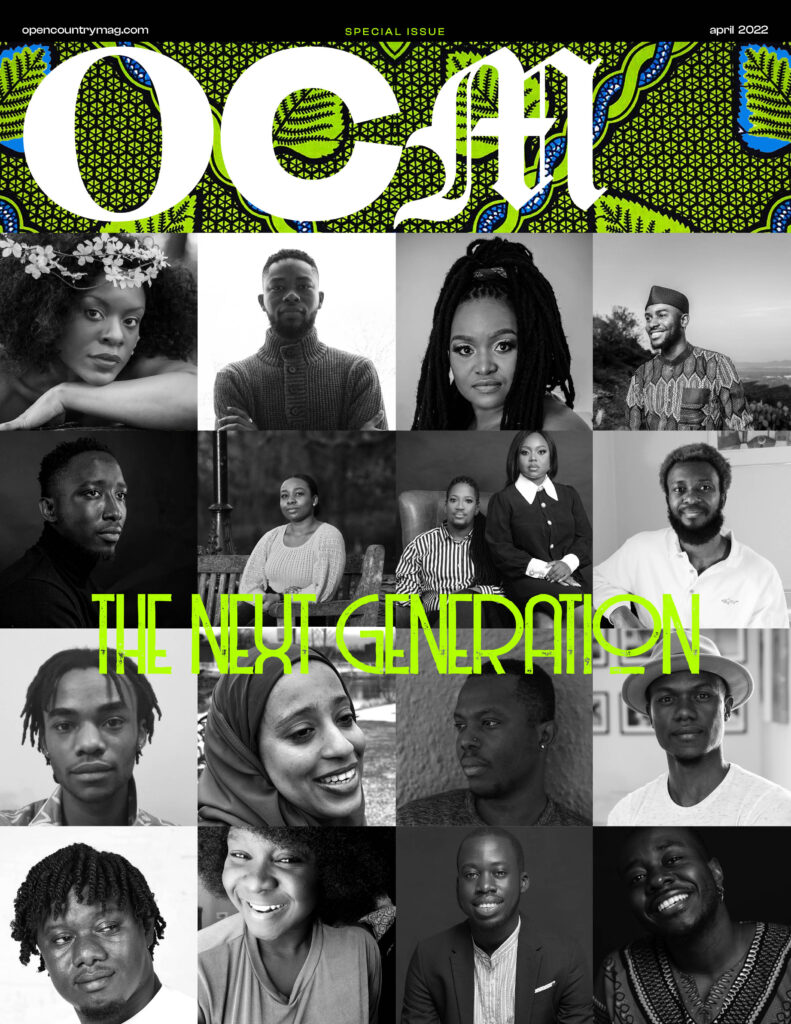

“Remy Ngamije on Doek! and the New Age of Namibian Literature” appears in The Next Generation special issue of Open Country Mag, profiling 16 writers and curators who have influenced African literary culture in the last five years, curated and edited by Otosirieze Obi-Young.

4 Responses