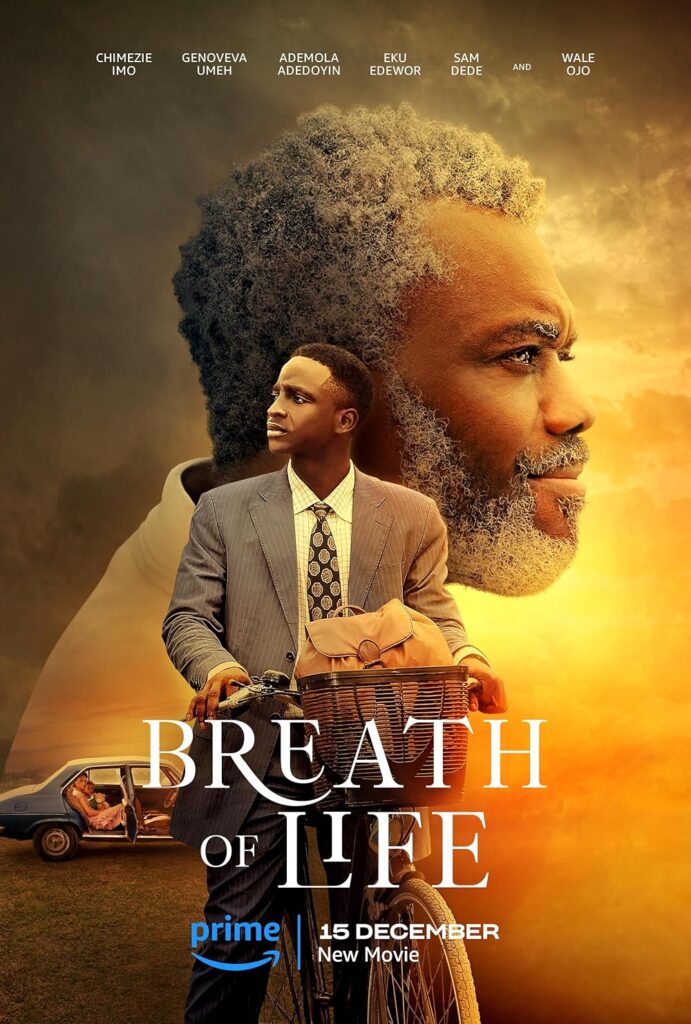

When BB Sasore’s God Calling premiered in 2018, it struck me as a visually enhanced version of just another Mount Zion film — unwaveringly faith-centered. God Calling won two awards from over ten nominations at the 2020 Africa Magic Viewers’ Choice Awards (AMVCAs), thanks to its makeup and lighting design. A standout scene, novel for Nollywood at the time, is an underwater shot capturing an attempted suicide at Third Mainland Bridge in Lagos. Six years later, after what seemed like an artistic hiatus, Sasore returned with Breath of Life, completing his trio of faith-based productions, including his first, 2017’s Banana Island Ghost.

Breath of Life follows Timi (Wale Ojo), a young clergyman with a messianic career. He is fluent in 16 languages (four of which are extinct), top of his class at Cambridge, and the highest honored cadet in his entry class of Her Majesty’s Navy. It is the 1960s when he returns to Nigeria, determined to revitalize the local church. He works alongside his wife and daughter, earning the love and respect of the community.

Things go south when Timi decides to testify in court against a murderous gang. What he doesn’t know is that the gang’s activities are covertly sponsored by the colonial authorities, to control the population and ensure compliance. Losing in court, Timi faces their retaliation: his wife and daughter are burned alive before his eyes. After trying and failing to end his life on several occasions, with bleach and bullets, this once bubbly reverend becomes a recluse. Thirty-five years later, another man emerges with a zeal to revive the local church and rescue Timi from grief’s long and winding embrace. It is Elijah (Chimezie Imo), his house manager. Their destinies intertwine.

In the execution of many faith-based films, there is often some struggle between artistry and didacticism. Most stray into overt sermonizing, ignoring whatever artistic intent should be given the production. With Breath of Life, it’s not just the Biblical rhetoric scattered throughout the dialogue that prompts my eye-rolls — understandable, given the need to cater to a predominantly religious Nigerian audience — but also the glaring inconsistencies in plot. One such inconsistency being how the film begins with exposing colonial injustices in the local community, their sponsored murders to exploit the populace, but portrays the church rather differently, in pristine and elevated light, as a salvific provision rather than the colonial instrument it is. The irony is certainly moving.

More so are the character inconsistencies, which stand out, in each case, like a white swan in a pond of ducks. It is in how Anna abruptly transforms from anti-Christian to a devout activist whose sole mission is to save the church. Similarly, Timi goes from yelling at Elijah, “Once a houseboy, always a houseboy!” to seeing him as a son and even willing all his property to him. How moving.

The deus ex machina absurdity of the ensuing violence, when Chief Okonkwo (played by Sam Dede) attempts to demolish the church, is rather disappointing and a lethargic attempt at bringing resolution to the conflict. It feels like another garish “God saved the day” scenario, lacking the artistic input needed to enrich the scene. Much of this plays out throughout the film anyway.

When Timi bursts into the old abandoned church to find his houseboy leading a Bible study with a small congregation, their ensuing verbal exchange had me snickering and questioning why dialogues in Nollywood movies often come off as contrived. I wondered if this was a deliberate theatrical effect or simply a lack of authenticity. The exaggerated accents only smeared the dialogues further. While I initially attributed the accents to an attempt at capturing the gentrification of Nigerians in the 1960s, they persisted even when the movie shifted across different time periods.

Speaking to The Guardian, Sasore explained that he wanted to capture a peculiar male-to-male relationship, a rarity in Nollywood where there are “a lot of women to women relationships, sisters, cousins, colleagues, people who are chasing the same guys, all kinds of things.” He wanted to explore male relationships defined by class separation and hierarchy. While Breath of Life succeeds in positioning the lives of these two men separated by class, religion, and belief systems, it fails to probe the depths of their characters.

Timi, a man who has lost both his wife and child, whose faith in God has faltered due to the prejudices he has faced, and who has made numerous suicide attempts to escape his grief, is not looked at as someone suffering and grieving. Instead, he is depicted as an alter ego who is angry at those who believe in God. This simplification reduces his complex struggles to a mere conflict of faith and, at best, anger, making it difficult for the audience to connect with his emotions. Rather than a man struggling to process grief, what we see is a bitter old man who points a gun at those who show up at his door unannounced, throws 15 plates of omelette against the wall to correct his houseboy, and resorts to verbal and physical abuse when his houseboy simply cannot drive properly. I am led to believe that the movie does not do justice to Timi’s character.

A defining moment in Elijah’s life is when he decides to give up his role as a houseboy to become a full-time pastor, despite having no idea how he will make ends meet. But the movie does not address how Elijah comes to his faith nor the life-changing events that make him an ardent believer in God, so much so that he is willing to throw his only source of income under the bus for the role. This is particularly important since Elijah’s mission to rescue the church is central to the plot.

Because plausibility is given very little consideration here, as in many faith-based movies, the result is a plethora of cringe-worthy scenes and inelegant acting. For instance, Anna thinks it wise to ask Timi for the 49 million Naira needed to save the church from demolition, despite knowing that he dismisses everything church-related and forbids his houseboy from mentioning God in his presence. Timi, who abandoned pastoring due to God’s betrayal, is suddenly invested in saving a church building worth millions. After the brief face-off with Anna, he inexplicably spends hours at his desk pulling up a solution to rescuing the church.

Elijah’s asthma could have made him a more relatable and sympathetic character, evoking empathy from the audience. However, the clichéd use of his inhaler quickly turns into a stereotype, undermining its intended purpose. It is only later in the movie that we learn of his complicated lung issues.

A near-constant in Sasore’s work is the depiction of intense, often painful spiritual journeys, marked by personal tragedy, internal conflict, and moments of divine intervention. Whether in the visually striking scenes of God Calling, the fantastical elements of Banana Island Ghost, or the melodramatic pulses of Breath of Life, he blends realism with spiritual allegory. He is an inventive filmmaker, but one whose talents do not yet equate to strong storytelling.

His settings are grounded in the material and social realities of Nigeria, and his works often take on a mythic quality, posing numerous what ifs. What if faith and redemption were far more complex and challenging than any religious doctrine could fully convey? What if the struggle between doubt and belief were the true driving force behind human existence? What if the power of faith was so overwhelming that it seeped into every aspect of reality, pushing individuals to their very limits?

Breath of Life and its tragi-comic resolution is worth noting for what it communicates to the many filmgoers who love it and have rewarded it. At the 2024 AMVCAs, it received 10 nominations and won a leading five bids, for Best Movie, Best Director for Sasore, Best Actor for Wale Ojo, Best Supporting Actor for Demola Adedoyin, and Best Supporting Actress for Genoveva Umeh. Expect it to be embraced by the more prestigious Africa Movie Academy Awards (AMAAs) as well. Still, when it comes to elucidating the motifs of the film — faith, redemption, and suffering — what Sasore does is far less illuminating than what he has already communicated in his cinematic oeuvre. ♦

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this review wrongly named Ademola Adedoyin, rather than Wale Ojo, as the actor playing Timi.

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

More Film & TV Reviews from Open Country Mag

— Ebrohimie Road, Reviewed: A Literary Legend as Father & Husband

— A Tribe Called Judah, Reviewed: A Box Office-Breaking Heist of Authenticity & Heart

— Jagun Jagun, Reviewed: New Heights for the Nollywood Historical Epic

— The Real Housewives of Lagos, Recapped & Reviewed: Glamour & Drama in Las Gidi

— Battle on Buka Street, Reviewed: Blockbuster Dramedy with Emotional Burn

— The Trade, Reviewed: Kidnappers Vs. Police

— King of Thieves (Agesinkole), Reviewed: A Captivating Yoruba Epic

— Gangs of Lagos, Reviewed: A Crime Thriller with Big Ambition

— Brotherhood, Reviewed: A Policeman and a Robber

— Shanty Town, Reviewed: Crime and Punishment, Fate and Freedom

— A Sunday Affair, Reviewed: A Stumbling Story of Romance and Tested Friendship

— Prophetess, Reviewed: A Modernist Portrayal of Faith

— Blood Sisters, Reviewed: A Rousing Murder Thriller

— La Femme Anjola, Reviewed: An African Neo-Noir Titillates in Crime and Lust

— Swallow, Reviewed: Perturbance in Ordinary Lives

— Ife, Reviewed: Lesbian Love in Bourgie Lagos

— Nne, Reviewed: Two Mothers and a Son

— The Men’s Club, Reviewed: A Charming Depiction of Male Friendship

One Response

What a beautiful piece!

Well-done, Iheoma!