By his early thirties, Wole Soyinka had established himself as a restless thinker and maverick in not only the creative and scholarly worlds but also in the political one. He was reported to have broken into the Western Nigeria Broadcasting Service studio in Ibadan after the 1965 elections, held the radio presenter at gunpoint, declared the election null, and asked the then premier of the region, S. L. Akintola, to leave town. His political activism was defined by militancy, but also by conscious humanism. By the time the Biafran War broke out in 1967, he was a lecturer at the University of Ibadan, inspiring among students, unpopular among colleagues.

Ebrohimie Road: A Museum of Memory starts just as he is arrested for visiting Biafra for peace talks, a time in his life documented in his memoir You Must Set Forth at Dawn. Following the scenes are interviews with his people, about how they took the news, and then a footage of him speaking after his release 26 months later, as the war was ending in late 1969. But this is only an enticing opener, not the central concern of the documentary.

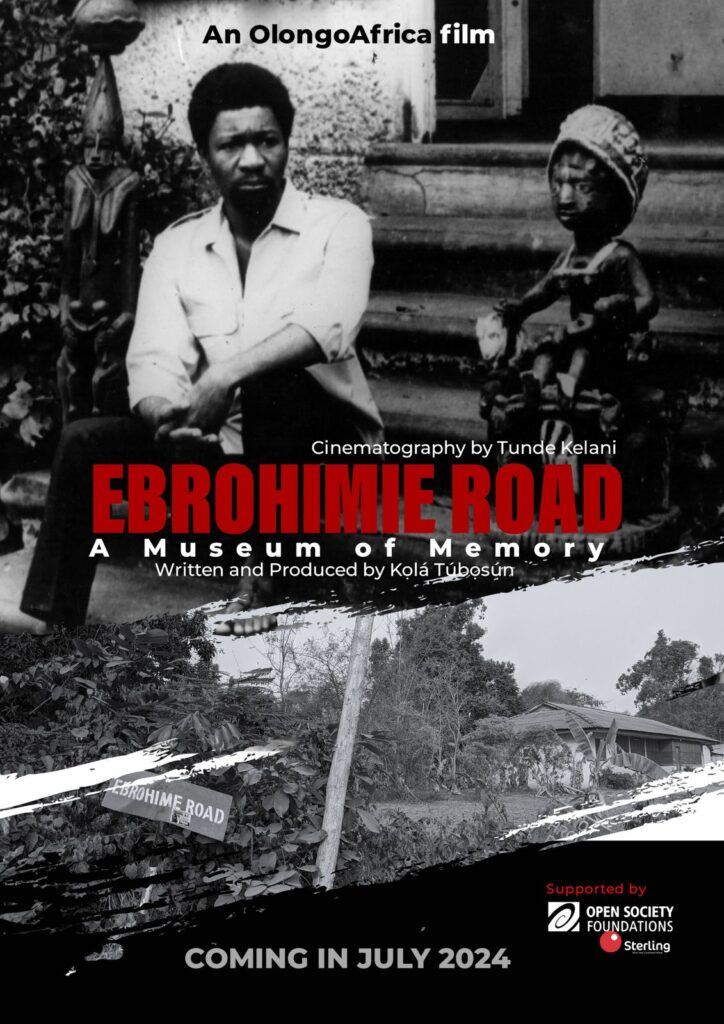

Written and produced by the poet, linguist, and OlongoAfrica founder Kola Tubosun, on the occasion of Soyinka’s 90th birthday on July 13, Ebrohimie Road centres on the house where Soyinka lived in Ibadan, recalling those eventful years from the points of view of his family members, students, friends, and current occupants of the house. The documentary — with cinematography by Tunde Kelani — peers into an itinerant, adventurous, and rebellious phase in the dramatist, poet, and novelist’s life.

At Ebrohimie Road, Soyinka lived with his former wife Olaide and raised his children: Olaokun, whom he had with a white woman in 1958, who returned to Nigeria in 1965; Moremi, the first child from his marriage to Olaide; Iyetade, who passed away ten years ago; Peyibomi; and Ilemakin, who was born in 1971, has “no memories of him [Wole] living in the house,” and describes himself as “the last Soyinka resident in the Ebrohime house.” As the Soyinka children and relatives focus on his domestic life as shadowed by his public one, some of his former students and current associates, including Niyi Osundare and Remi Raji, narrate the image of his public life. These arcs give the documentary a polaroid quality.

In the house, Soyinka was restless, and his children had to adapt to the theatricality of their home, which, though quiet and secluded, was a haven for rehearsals. He was also a tireless traveller, to the extent that everyone became used to him being away for long, so much so that when he was arrested, it took a while for the family to learn so. A pariah in Ibadan academia, he was denied due professorship in 1971 and was made Head of Department only provisionally, rather than as a fixed appointment. One gets a sense of an abusive relationship until he resigned in 1973, to accept a fellowship at Cambridge.

The people in Soyinka’s lives experience him in different ways. Now in her mid-80s, his wife Olaide — whom he divorced in 1985, the year before he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature — remains agile in mind and speaks with the eloquence of youth. She tells us that she married him because of their shared interests, moved closer to the campus because of him, and took a degree in Library Science, all the while caring for the family in his absences. She had moved so much around for him that when he got the Cambridge fellowship, she chose to finally focus on herself rather than follow him abroad. The documentary casts their marriage as an eventful one in its first decade, with its own fair share of chaos.

The members of the Soyinka family come off as discreet but open enough to tell their stories, in a not very glamorous way. His son Olaokun confesses to not understanding and searching for evidence, at home, of the heroics for which his father was adulated. His daughters Moremi and Peyibomi, interviewed together, review their parents’ marriage. “We used to ask my mother,” Peyibomi jokes, “you did not see all those quiet professors, doctors?” Why him? What did their mother see in a man of their father’s character?

“My children ask me if I love him,” Olaide shares. “Of course, you don’t marry a man you don’t love.” She once said in an interview that Soyinka was more absent than present as a father. And Soyinka’s current wife, Folake Doherty-Soyinka, once joked about him being not just a visiting professor but a visiting husband. In these, one gets the sense of an erratic but charming man, who still manages to keep his spot in the hearts of the people in his life.

Today, the Ebrohimie house, unlike when Soyinka lived there, is largely deforested, and Soyinka abhors that. He remembers his enthusiasm in acquiring it, but his relationship with it is like that between a man and a former friend; although he has good memories of them, he is apprehensive of a reunion. “Not a ghost of a chance,” he says about visiting the house.

“In the aftermath of every place, Dad had always experienced anger and loss,” says his daughter Peyibomi, a professor at Ithaca College. And it came from how the places were handled after he left, especially the deforestation.

A former resident tried to make the house into a museum and failed. There have been little or no attempts by the Oyo State Government or the Federal Government to preserve the house. (I presume that it might be because, for decades, Soyinka had been at loggerheads with successive governments and his houses have been raided by security forces.) The documentary sheds light on the lacklustre attitude in Nigeria for the preservation of artistic and cultural edifices.

Soyinka earned his legendary pedestal in African literature. In the immensity of his character here, this brilliant, fierce, and restless young man, one sees what young creatives and thinkers today should adopt and what some have adopted. For a writer like me, in whose child mind Soyinka occupied a heroic status because of his face-offs with the government, it was animating watching Ebrohimie Road. Yet the documentary is curious in what it leaves out. It could have shed more light on his bulldozing activism. The documentary shows him as the fascinating and controversial personality we know him to be, but what we needed were more fully sketched details of his actions. What, for instance, was his family’s reaction to his radio house stunt in 1965?

Soyinka’s stance on Biafra, the poet Odia Ofeimun says, was: “Those who were against secession had a point, so to say, but . . . the destruction which was taking place was simply unnecessary for what they were trying to achieve.” What Soyinka wanted, Ofeimun continues, “was a situation whereby both sides ought to be made to stop for a proper discussion to take place. That proper discussion did not take place during the Civil War. And every attempt to make it take place since then has been disrupted.” It’s an interesting highlight for the documentary, because it is its only engagement with the aftermath of its sensational Biafra arrest start. The documentary needed more elucidation on the topic of Biafra. It needed the relevance of Soyinka’s stance to present-day Nigeria, especially as government-backed anti-Igbo sentiment has climbed back almost to the levels it was around the war.

The Soyinka of the Ebrohimie years was not someone the Nigerian state idealised, but the Soyinka of today happens to be that. The Nobel laureate is widely perceived, in his refusal to criticize him even with allegations of corruption, election manipulation, and drug-trafficking, and evidence of anti-Igbo organisation, to be a key ally of the Nigerian president Bola Ahmed Tinubu. This year, the president renamed the National Theatre in Lagos and a highway in Abuja after him. (President Tinubu also named a highway in honour of the late Chinua Achebe, who had a history of rejecting national honours.) At the same time, Soyinka has consistently attacked Peter Obi, an ethnic Igbo and the presidential candidate embraced by the youth for his stance against corruption. For many young Nigerians, whose protests he has misrepresented as “fascism” while keeping silent on their oppressors, Soyinka’s place as an activist icon is now fractured. While this gives a louder significance to the gaps in its engagement with the subject of Biafra, the documentary does well to establish its importance elsewhere: the preservation and projection of memories.

In this sense, Ebrohimie Road is an effort to seal a legacy by enlisting the one group with perhaps the most defining private perspective: family. It is even more remarkable given the recent unravelings, at the hands of family, of once-untouchable literary legends. In March, Kenya’s Ngugi wa Thiong’o was accused by his writer son of beating his wife; and weeks ago, Canada’s Alice Munro was revealed to have protected her husband who sexually abused her daughter. In this context, even as part of his public legacy is under re-evaluation, Wole Soyinka’s personal one takes a victory lap. ♦

Edited by, and with contribution from, Otosirieze.

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

More Film & TV Reviews from Open Country Mag

— A Tribe Called Judah, Reviewed: A Box Office-Breaking Heist of Authenticity & Heart

— Jagun Jagun, Reviewed: New Heights for the Nollywood Historical Epic

— The Real Housewives of Lagos, Recapped & Reviewed: Glamour & Drama in Las Gidi

— Battle on Buka Street, Reviewed: Blockbuster Dramedy with Emotional Burn

— The Trade, Reviewed: Kidnappers Vs. Police

— King of Thieves (Agesinkole), Reviewed: A Captivating Yoruba Epic

— Gangs of Lagos, Reviewed: A Crime Thriller with Big Ambition

— Brotherhood, Reviewed: A Policeman and a Robber

— Shanty Town, Reviewed: Crime and Punishment, Fate and Freedom

— A Sunday Affair, Reviewed: A Stumbling Story of Romance and Tested Friendship

— Prophetess, Reviewed: A Modernist Portrayal of Faith

— Blood Sisters, Reviewed: A Rousing Murder Thriller

— La Femme Anjola, Reviewed: An African Neo-Noir Titillates in Crime and Lust

— Swallow, Reviewed: Perturbance in Ordinary Lives

— Ife, Reviewed: Lesbian Love in Bourgie Lagos

— Nne, Reviewed: Two Mothers and a Son

— The Men’s Club, Reviewed: A Charming Depiction of Male Friendship