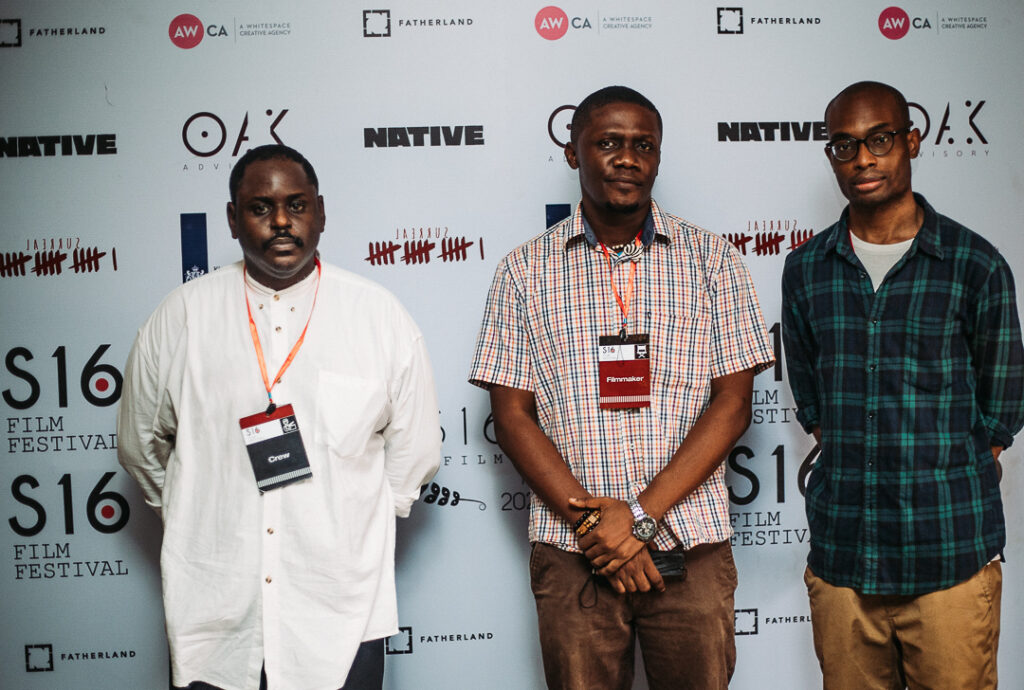

On a summer evening three years ago, in a flat in Paris, three Nigerian filmmakers trembled with joy, luxuriating in the afterglow of their latest feat. The trio — Michael Omonua, C.J. “Fiery” Obasi, and Abba T. Makama — were members of a group called the Surreal16 Collective, forged in their break from Nollywood orthodoxy. They had just arrived by train from the Locarno Film Festival, where their anthology film Juju Stories premiered and won the Boccalino d’Oro prize for best film. It was an international recognition of their talent, a sign that they were Getting There. They bantered. They were “on a post-Locarno high,” Omonua told me recently. “We felt untouchable that day in Paris. It felt like everything was possible.”

They agreed that it was egregious that the Nigerian filmscape lacked outlets for left-field talents to express themselves freely. The country’s most prestigious festival, the Africa International Film Festival (AFRIFF), where they would win Best Director for Juju Stories, screened all sorts of films, but there were no festivals to champion films that veered from established doctrine. Films that, because of their subject or style, stood no chance at the box office. Arthouse films like theirs. “We felt there were no ‘filmmaker first’ type festivals,” said Omonua.

On that rapturous Paris evening, the three men, impelled by a kind of Dutch courage, were not yet thinking about the challenges of organizing a festival, the challenges of money and of their inexperience as showrunners. They were not yet thinking of time, how little there was to cobble together a festival within four months. They had not yet dealt with the ultimate challenge: selling an unusual product to an indifferent customer. Such a festival, they imagined, would neither excite investors nor the mainstream audience. It may turn out to be a merry chase, fated to collapse in no time.

Yet over the following three years, their S16 Film Festival grew, flashier and better than at its start, when it drew over two hundred people to the old Federal Printing Press on Broad Street, Lagos Island. Its fourth edition will take place this month at the Alliance Française in Ikoyi, the sedate-white villa that is a popular site for cultural events. Themed “Technologic,” it promises an upgrade from earlier editions and expects a larger turn-out. It will screen sixteen films, a record high, a potential nod to its name and stylization as XVI.

Opening the show will be On Becoming a Guinea Fowl, by the Zambian Welsh director Rungano Nyoni. The surrealist black comedy drama, a Cannes selection for Un Certain Regard, is about a Zambian family’s reckoning with sexual abuse. Also screening will be Tobi Onabolu’s Danse Macabre, which considers the relationship between the conscious and the unconscious, using poetry, dance, music, and archival audio, and borrowing from Ingmar Bergman and Marina Abramovic.

Another, Baptized by Fire, from Kach Offor, visits the dangerous world of drug dealing. But it is Dika Ofoma’s God’s Wife that has whipped up the most anticipation. The short shows a devout Catholic woman, played by newcomer Onyinye Odokoro, negotiating the misogyny that attends widowhood.

Ofoma, whose films screened in the last two editions, told me that the festival is a great ally to young Nigerian filmmakers. “It’s giving us room to be different,” he said. “I like to think of the Surreal16 Collective as pioneers of a new kind of Nigerian cinema, and their global success has proven that it’s possible to tell stories in the way you want to tell them.”

Omonua, Obasi, and Makama first crossed paths in 2014. Makama reached out to Obasi on Facebook, to congratulate him for winning the Best Nigerian Movie award at AFRIFF, with OJUJU. Obasi wrote back, telling Makama about a “really talented” filmmaker he met at the festival. “It was immediately obvious that the three of us had a lot in common,” Obasi told me. They shared an irrepressible impulse to swim against the frothy tide of industry convention, to make films that challenged popular assumptions of what a Nigerian production should be.

Obasi certainly meant to push the envelope with OJUJU, which situates the zombie genre in a Lagos slum. Makama animates his films with Jungian thought, like in 2019’s oneiric The Lost Okoroshi, in which a security guard wakes up as the titular masquerade. And Omonua’s work, with influences ranging from Wong Kar-wai to the Belgian Dardenne brothers, spotlights the grimy underside of contemporary Nigerian society. His Sún Ejè, from 2014, and Yahoo Boy, from 2016, look at the organ trade and cyber-crime, respectively. The themes they explore, and the ways they do it, place them in the same filmmaking class as Kenneth Gyang, Daniel Oriahi, Chuko and Arie Esiri, Ifeoma Chukwugo, and Mildred Okwo.

In 2016, Omonua, Makama, and Obasi met at Ikeja City Mall and teamed up. (The 16 in Surreal16 is the year they founded the Collective.) Together, they became a kind of vigilante force, guarding against what they called a “cinema landscape dominated by slapstick comedies and melodramas.”

They formalized their grievance with a manifesto, a tongue-in-cheek list of sixteen Dos and Don’ts for filmmakers, including: “Avoid Melodrama” and “No establishing shots of Lekki Bridge.” They urged filmmakers to embrace “an element of surrealism.” They were inspired by The Vow of Chastity, the manifesto by Dogme95, a late-90s movement to purge Danish cinema of what it believed were obnoxious Hollywood influences.

The Surreal16 Collective see in their festival an opportunity to propagate their principles. “We still believe in the manifesto — that if you abide by it, consciously or not, you will push the limits and explore the cinematic art form in an innovative way,” Obasi said. “The films we select will always fit with the manifesto first, before anything else. That’s what we really celebrate at the S16 festival.”

Sitting in the Alliance Française’s dark theatre last December, I wondered how much it cost to rent the space, if it burned a hole in their purse. But Omonua explained that the French Embassy covered the cost. It freed the Collective from the pressure of raising funds for a venue, which they struggled to do for the first two editions.

“Sometimes we didn’t get funding until a week before the festival,” Omonua said. “Yet we had to pay vendors, to pay for a venue, and for toilets, a generator, and sound systems.” That the festival’s new home came with a DCP — Digital Cinema Package — and standard cinema projection was an additional perk. Poor projection quality marred the first edition.

The Collective also found an eager ally in the Dutch Embassy, and in some private companies who, Obasi said, “saw the vision.” Companies like A White Space Creative Agency, who helped to organize the festivals, and Quacktails, who plied festivalgoers with free drinks.

There is even more support this year, through partnerships with Mostra de Cinemas Africanos, the Brazil-based film festival, and with Open Doors, the Locarno Film Festival project that supports independent filmmakers.

“It’s not just a money problem, it’s also the time it takes to put a festival together,” Omonua said. To work around the problem, the Collective uses an invite-only model, rather than a call for submissions. It saves them time they would have spent scouring hundreds of emails for the Next Big Thing. Omonua said that selecting the films themselves ensures a fidelity to their ethos, but that “one day, hopefully, we’ll have the means of hiring an artistic director to curate the films.”

One disadvantage of the Surreal16 Collective curating their own festival, as the film critic Oris Aigbokhaevbolo has written, is that it might “present a conflict of interest and maybe a narrower view of the landscape.”

Omonua disagreed: “The programming could sort of narrow down tastes and whatnot, but I don’t see the problem.” He cited festivals curated by filmmakers, to show that it is an acceptable practice. “There is Directors’ Fortnight in Cannes, and I believe ACID is also programmed by directors. I think, between myself, C.J., and Abba, we can watch stuff and be, like, ‘Oh, wow, this is good.’ I don’t even have to like the film, but I can appreciate what the film is trying to do.”

Aigbokhaevbolo also observed that the festival drew a niche crowd, an “alte crowd,” as he put it. “The audience would need to expand,” he charged. At the festival’s after-party last year, held at an open garden spread in the Dutch consul Michel Deelen’s home, I, too, noticed that the festival attracted a certain type of Nigerian: the Ikoyi habitué with lots of disposable income. The film critic Daniel Okey told me that it is one of the festival’s shortcomings, but only because “looking from the outside, it looks like the Collective also wants to be in the mainstream.” “The question,” Okey said, “is how do you make more people interested in a niche festival?”

Omonua believes that the answer lies in Nigeria’s current economic set-up, which makes cinema “an elite sport” for many Nigerians. “I’d love to get more people from diverse backgrounds to attend. Not to say we’re limited to elites. I don’t even know what that means. I mean, are we getting people from the poorest parts of Lagos to attend? Probably not. But are they going to the cinema anyway? Probably not. We want people to come, but I think all that kind of work will be done as the festival grows overtime.”

This year, Obasi’s O-Town, from 2015, will screen as part of a retrospective. His Mami Wata was last year’s main attraction, with attendees dressed in black and white, in tribute to its black-and-white cinematography. Mami Wata was Nigeria’s first film to premiere at Sundance, where it won the Special Jury Prize for Cinematography. It is the closest the Surreal16 Collective has come to commanding national attention, as Obasi’s film grossed two million naira during its first weekend in theatres. Omonua said that its success gave the festival sheen and heft: “Mami Wata definitely added prestige, if I can use that word. The thing is that any sort of individual success we have will always give our festival more prestige.”

The Collective is now focused on giving filmmakers the means to thrive post-festival, long after the Alliance Française’s doors have closed behind them. It hopes to do this with its international collaborations. There will be a workshop on festival strategy, led by Mostra de Cinemas Africanos curator Ana Camila Esteves. “We are trying to be a place where filmmakers can take themselves to the next level,” Omonua said.

When I asked how they have kept the festival running despite the odds, they pinned it to devotion. “Love is how we keep it going,” Obasi said. Omonua concurred: “It all comes down to passion. It all comes down to a belief that there is potential in films with unique voices.” ♦

The S16 Film Festival is set for December 10 to 13, at the Alliance Française, Ikoyi, Lagos.

CORRECTION, Dec. 6, 8:35 A.M. CT: An earlier version of this piece wrongly attributed ownership of the Alliance Française, Ikoyi, to the French Embassy. The Embassy only covers the cost for the S16 Festival venue.

Edited by Otosirieze.

If you enjoyed what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

No One Covers Nollywood Like Open Country Mag

— How Tolu Obanro, Nollywood’s Top Composer, Crafts the Sounds of Its Biggest Hits

— The 10 Best Films & TV Series of the Year

— The 10 Best Acting Performances of the Year

— A Tribe Called Judah, Reviewed: A Box Office-Breaking Heist of Authenticity & Heart

— Rita Dominic‘s Visions of Character

— The Epic, Transformative Comeback of Chidi Mokeme

— How Mami Wata Swam to Sundance

— How Dakore Egbuson and Tony Okungbowa Traverse Trauma in YE!

— Writing Omo Ghetto: The Saga, Nollywood’s Highest Grossing Film of All-Time

— How Yahoo+ Captured a Desperate Side of Internet Fraud

— Awaiting Trial: Families of SARS Victims Speak in Devastating Documentary

— Country Love Depicts Tenderness in LGBTQ Lives

One Response

Insightful read. I reckon that screening films being a very niche thing, is not the type of thing I’d enjoy. But hey, I understand and appreciate what they’re trying to do.