I.

The Road

The long road lay barren of light, but through drab villages of farmers and traders, the noise of a bike was not strange at night. Before him, Benin Republic, his faith in a foreign country; behind him, Nigeria, his hope and mission, in the grip of dread and death, at the mercy of a butcher, General Sani Abacha. Shrill on his skin; it was November and harmattan bit; it was 1994, a full year since Abacha seized power, leaving in his wake a trail of barbarity that the country had not witnessed since the Biafran War, when the young soldier made his name turning the already surrendered Midwest Region into a killing field.

If anyone had doubts about the depths that the country could plunge to, the butcher woke them up. Bodies piled up. Activists rallied tighter. They needed an opposition radio to reach the masses, and they believed that only someone with the name, courage, and record of Wole Soyinka could help coordinate an international pressure movement — doable only from outside the stringently surveilled state. Only a year ago, he had forced himself into the country, defying warnings and evading arrest. He needed to reverse it, to smuggle himself out.

The plan was months in the making, a system of false trails and improvised exits awaiting his activation, for him to willfully go on self-exile. The Nigerian Secret Security Service (SSS) kept spies around his residence in Lalubu Street, Abeokuta, tracking even his four-year-old son to school; and to distract them, he announced rehearsals for his new play The Beatification of Area Boy, in which a rich bride deserts her rich groom and chooses a local tout, creating commotion that required military intervention. The set bustled with people and costumes, and, in that rowdiness, he stole away.

He and his motorcyclist rose before dawn in Oyo and made their way to Iseyin, waiting there until evening, to be joined by more motorcyclists. His heart in his hands, they sneaked south to Lagos. Then a nine-minute canoe crossing, during which he kept his hand on his Glock pistol, and his eyes on a crew member he suspected was a spy. On the foreign soil of Benin, their bike sped away from the unmarked border, his senses wild awake.

Many times, in his life, people had told him that he was in danger, but only twice did he believe it. The first time, in 1990, he was in Jamaica, visiting a village of dying Yoruba heritage named Bekuta, imagining being buried there, an ocean and continent away. Yet that was during General Ibrahim Babangida’s regime, and Babangida was a known quantity: he stole money, harassed the press, killed opponents he couldn’t compromise, but he had limits.

Which was why when he promised a return to democracy and then annulled the 12 June 1993 election, he caved to international pressure and installed Ernest Shonekan as Head of the Interim National Government. Abacha was Defense Minister, and all he had to do was open his hands and grab power. Years later, as he tightened his grip while the resistance worked to loosen it from abroad, Abacha would ask in an interview: “That Wole Soyinka; he is supposed to be a poet, but what he does is throw bombs all over the place; is that the function of a poet?”

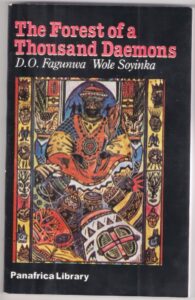

Swarms of fireflies lit up the bush, and he thought of scenes in a book, Ogboju Ode Ninu Igbo Irunmale. It was by D.O. Fagunwa, the first novel in the Yoruba language; it was a book he translated in prison as The Fearless Hunter in the Forest of a Thousand Demons. It was the worst thing he survived: his four by eight feet cell. For 26 months during the war, from 1967 to 1969, he sat in solitary confinement in Kaduna, for defying then head of state General Yakubu Gowon and seeking to mediate between the Federal and General Odumegwu Ojukwu-led Biafran sides.

An avoidable war: three million dead, the old Eastern Region decimated. Starvation as a war weapon was the brainchild of his Yoruba tribesman Obafemi Awolowo, who reneged on his word with Ojukwu and the Igbo. Prison assaulted his sanity, and he survived it by fasting to harness creative clarity, by translating Fagunwa, and by drafting on rolls of tissue his own memoir, The Man Died, and the poems in Poems from Prison, later expanded into A Shuttle in the Crypt.

After release, he survived news that Christopher Okigbo, the fiery poet and his friend from the University of Ibadan, had died at the front. Later, in March of 1986, he and the two other members of that famed Ibadan quartet, Chinua Achebe and J.P. Clark, survived the execution of another poet, the military man Mamman Vatsa, hours after they went to General Babangida to intercede for him. Seven months later, on October 19, only three days after he was announced winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, the whole nation survived the assassination of the journalist Dele Giwa through a letter bomb. He was watching friends and allies be plucked off by successive regimes.

He did not know it then, but exactly a year after his escape, Abacha would execute eight Ogoni activists, including the writer Ken Saro-Wiwa, for protesting oil devastation in the Niger Delta; and the year after, Kudirat Abiola, the wife of M.K.O. Abiola, would be assassinated; and two years after, Abacha himself would die in the company of escorts, and General Abdusalami Abubakar would take power; and only a month later, M.K.O. Abiola would die after sipping tea in the company of American officials. An assassination that Soyinka, helpless to do anything, had been tipped off about days before it happened.

In the bush, they rode for ten hours, and on that motorcycle pillion, his thighs ached with such intensity that he feared he’d damaged his muscles. Vicious tree branches lashed at them; he wondered if the forest was angered by their disturbance of its peace. For strength, he pondered the many faces of Ogun, his muse and possessor, Ogun the god of iron and war and poetry, the initiator of destruction and rebirth; the “godfather,” he’d written in his poem “Idanre,” “of all souls who by road / Made the voyage home.” He ached about his family. There was dust in his throat, pollen, bugs, and grime he could taste. On his tired shoulders were hoisted the hopes of a nation’s activists, but as the bush track gave way to untarred motorable roads, all his desires, worldly and spiritual, pared down to something banal: cold shower and beer.

He was 60 years old, entering the third half of his life. More than fear, more than pain, more than exhaustion, what he held in his heart was deep resentment. How could it be that, after everything he had suffered, he was yet again on the run? The SSS had a code name for a potential Operation Arrest Wole Soyinka. They called it “Antelope.” Their target was a hunter and they were making him game.

II.

The Wound

In the rainy season, when local hunters were least adventurous, graceful antelopes skip across the deep forest in Abeokuta where Soyinka lives. He bought the land in 1984 and built it — a red brick structure filled with art like a museum, surrounded by palm trees and behind which is a little stream — with his $290,000 Nobel windfall, and only a few years later had to rebuild it after Abacha’s men invaded it. On that morning of his forced self-exile, he had taken a walk in a different bush, watching birds, wishing he had taken two fallen ones on that gruesome journey, as barbecue. Thirty years had now passed and no one was at his back, and he was still roaming forests. He thought of these strolls as him repossessing nature. The thicket was awash in rainwater, the ground muddy, though his steps, even as a nonagenarian, were no slower than they were decades ago, despite all he put his body through.

That nonagintennial provoked a wave of events and tributes to his work, but mostly to a life rinsed in fire. If it bothered him that most questions he got were about politics and not literature, about his activism and not his over 50 books, he did not complain. He belonged to an African generation whose artistic input came with sociopolitical import, who were used to the latter overshadowing the former. They were a singular group of artists and curators born in the 1930s — including the writers Achebe, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Lewis Nkosi, and Duro Ladipo; the musicians Miriam Makeba, Fela Kuti, Hugh Masekela, Mike Ejeagha, and Ali Farka Toure; the designers Shade Thomas-Fahm and Juliana Norteye; the painters Ibrahim El-Salahi, Mohammed Melehi, Bruce Onobrakpeya, Skunder Boghossian, Malangatana Ngweya, and Demas Nwoko — who innovated with indigenous inspiration and re-presented African thought in a nascent postcolonial world. They broke down barriers of form and meaning and forged a bridge to the Black Diaspora, strengthening a sense of shared destiny. They knew what they had done and did not wait to be validated. Most had passed on but left outsize legacies still uncovered. He was one of the few in that literary cohort who worked complexly in every genre: drama, criticism, fiction, memoirs, translation, poetry, and editing; even venturing beyond, into singing and acting.

Unlike many of his peers, fiction was not his forte. Drama was. And in that genre, in play after play, he pulled from Yoruba mythology, locating his characters in tragic torsions cast across the realms of the living, the ancestors, the unborn, and the transition, their comic cracks derived from brushing against a modernizing society. He poked and upturned the conventions of a European theatre stuck on Shakespeare, Moliere, and Ibsen, installing African metaphysics as fecund sources of lasting insight. He backed it up in pithy polemic displacing Western fixation on “ideology” with an African anchoring in “social vision.” He described his immersion in local lore as “the drama of the gods,” raising an art form to ritualistic heights. He did not only carry on that Yoruba literary tradition of the dynamic, fulfilled individual upon whom the community may look to for service — a heritage committed to Yoruba language writing by Fagunwa and brought into English by Amos Tutuola — he looked to its originating mysteries in Ogun, the very heart of Yoruba tragic art, and seemed to live it.

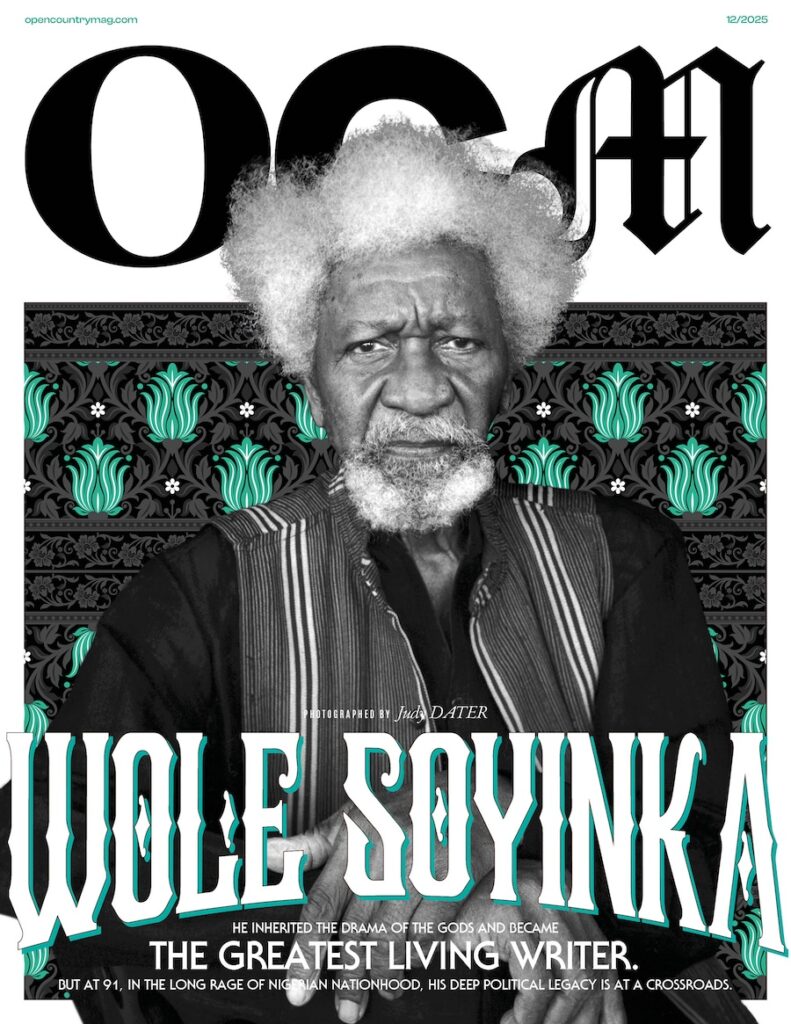

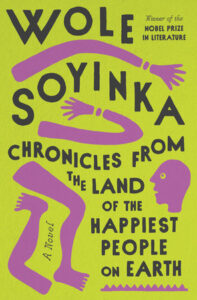

The psycho-politics of his literary and activist work were not only continental, not solely African, they were also racial, consciously Black, and in 1986, that belligerency made him the first writer of both heritages to be honored by the Swedish Academy, at the age of 52. It kept him carving, in the 40 years since, more works of equal consequence, so that, by range and longevity, the mantle of “greatest living writer” fell to him. A title few offered writers outside the cultural West. Absent that acknowledgement, his third novel, Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth, was received with commensurate fanfare, and younger writers, from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie to Ben Okri, lined up in praise of him.

At the threshold of the fourth quarter of his life, he had picked a few lessons, and one was the sanctity and sanity of friendships. He made them many and stayed in deep, because they were what saved his life, gave him a network of assistance when he needed it. Now that he was no longer running, those friends celebrated him the loudest. He had gone from being hunted by Nigerian heads of state to being celebrated by the new one, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu. For the first time in his life, the most powerful person in the country was his friend. For the first time in his country’s life, too, even as it sunk deeper, the ruling government toddled without criticism from him.

If he finally felt relief from decades of running, it was thorned: by mending his relationship with the Nigerian state, he ruptured his once sacrosanct standing with the country’s largest demographic: its still-suffering young people. Far away from the solitude of his forest, as the literary world and the Nigerian political and corporate establishments collided in annual exultation of him, that generation brewed with rebellion. He, Soyinka, brewed with aversion. And with the 2023 elections, with his withering criticism of the presidential candidate Peter Obi who was powered by an unprecedented populist movement for change, the standoff erupted into open acrimony.

He had received sainthood before death and de-canonization may feel like being skinned alive. He saw it through the lens of his life. He had slept and wept in damp cells and fled and wept across borders so that he could reach home, fight for home, and home he now was; how dare anyone look at him, after all these years and sacrifices, and say to him: Do not speak? He took it as the deepest insult, a late life wound that may not heal.

His sense of humour was intact, though. When people came to pay him homage and were stunned at his health, his harried gait and vitality that defied decades of smoking, stress, and reckless living, his sharp mind and photographic memory, he told them that he’d already made arrangement for his death. And, as if to rub it in, he told them, too, that his favourite song was “Zombie,” the 1976 track by his cousin Fela Kuti that aggravated the military to invade and burn his Kalakuta Republic:

Zombie no go go, unless you tell am to go (Zombie) . . .

Zombie no go think, unless you tell am to think (Zombie).

Walking in his forest, Soyinka liked to contemplate that song for its mutinous tang, for the way it defined the Nigerian character, for how it took him back. The young him was a restless rebel of the first rank, and the old him might see how his early work foreshadowed, in contradictory ways, where he now was.

III.

The Fire

Soyinka was 26 years old in 1960, a Research Fellow in Drama at University College, Ibadan, when he produced A Dance of the Forests, the play that made him his first political enemies. It was a work meant to celebrate Nigeria’s independence but was pulled from the program of events because it projected a country in unresolved tension with its past, striding into an unplanned future.

The setting is a small Yoruba community some of whose indigenes lived as a king’s courtiers but now exist in the afterlife as guests of the benevolent Forests. Among them walk unreturned ghosts from the court and watching it all are rival spirits and deities. As a welcome gesture, the Forests have set a Feast of the Human Community, and chosen Demoke, a carver who was a poet in his former life, to erect a symbol of reunion. Possessed by the mischievous Ogun, Demoke has carved the araba, the sacred tree of Eshuoro, a wayward spirit. When his apprentice protested, Demoke, working below him on the tree, pulled him down to his death. Later, presenting himself as a mere observer, Demoke tells his companions, “There is nothing ignoble in a fall from that height. The wind cleaned him as he fell.” As the play proceeds with verve and proverbs — characters arguing about the glory of the ancient empires of Mali, Songhai, and Chaka, debating the nature and intent of corruption — Eshuoro ventures out for vengeance, tracking an artist whose lifework has been erected on innocent blood.

Meanwhile, in an earlier storyline before their deaths, the human king Mata Kharibu has stolen a brother chieftain’s wife and confronts a warrior who challenges it:

MATA KHARIBU [advancing slowly on him]: It was you, slave! It was you who dared to think.

WARRIOR: I plead guilty to the possession of thought. I did not know that it was in me to exercise it, until your Majesty’s inhuman commands.

[Mata Kharibu slaps him across the face.]

. . . . . . . . . .

MATA KHARIBU: Madness! Treachery! Frothing insanity traitor! Do you dare to question my words?

WARRIOR: No, terrible one. Only your commands.

Before A Dance of the Forests, Soyinka had staged two plays and burned one. At the time, he was on a journey of rediscovery. The country he believed in was not what was, the continent he knew had not yet become, and the future lay in the potter hands of the youth. He’d finished from Ibadan in 1954, with a degree in English, History, and Greek, and moving to England, to Leeds University, he joined other African students trooping to London, working as railway and postal porters. At their gathering places — the West African Students Union in Porchester Terrace, Bayswater, the Overseas Students Club in Earl’s Court, the University of London Students Union — one subject persisted: the protracted end of colonization.

It was the mid 1950s and the West African colonies were negotiating their freedom, but in East and Southern Africa, the situation was fraught. The Portuguese imposed assimilationism in Angola and Cape Verde, the British were brutalizing Kenya in a bid to quash the Mau Mau Revolt, but it was in South Africa that European racism beamed unblinking in the Apartheid system. The students understood British racism: the passengers who avoided sitting next to them on buses, the shopkeepers who ignored them; and, as barricade, they decided that Africans held mental superiority. Their White classmates were, after all, less smart and couldn’t even point to Africa on a map; and worse, they lacked hygiene. British racism, they joked, was nowhere near Apartheid, and British racism would wither once they wiped out Apartheid.

So invested were they in the self-determination of Black South Africa that they prepared for an inevitable racial war. They took it not as intuition or revelation, not as blind faith or ambition; they took it as knowledge, as the destiny of their generation. The Organization of African Unity (O.A.U.) did not yet exist, but the continent’s antagonistic Monrovia and Casablanca blocs were on the road to a common vision. So the students prepared.

As a writer, Soyinka saw precedent in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, one of several volunteer international forces of writers and artists formed during the Spanish Civil War of 1936. He enrolled in the Officer Training Corps infantry, hoping to take advantage of the training, but when the Suez War broke out the following year, in 1956, and Britain and France occupied the Egyptian canal, he was blindsided to get a call-up letter. He did not know that “colonials” had to fight for Her Royal Majesty, and refusal meant court-martial. He told the deployment office that he was Nigerian. They reached a legal resolution: he was not from Lagos, a proper British colony with quasi-British passport carriers, but from Abeokuta, a town in the interior and therefore “protected” under second-class citizenship. For the first time in his life, he was grateful to be considered second-class.

But he was a restless young man and soon signed up to support British troops fending off the Soviet invasion of Hungary. He wrote to his father, who wrote back: You were sent over there to study . . . if you feel inclined to jeopardize your studies . . . return home and make this your battlefield. He was angry at his father and refused to write him more letters. But before he could join the war, the Soviets overran Hungarian resistance.

The more he wanted to do, the more he had to say, to write about. After an encounter with a White landlady who wanted to know how dark he was before renting to him, he wrote “Telephone Conversation,” and delighted in reading that poem on the BBC radio. For months, he deployed vengeful symbolism on a play about a Boer family trapped in their farmstead, eaten alive by black soldier ants. A White professor told him that it had too many “purple passages” — a phrase he hadn’t heard before. The play had the heavy imprint of Eugene O’Neill anyway, and after failing to efface that influence, he set those tens of sheets of paper on fire. It was, as he later told it, “the first auto-da-fe of my career.”

His next play was shorter and had fictional fire in it. In its climax, White scientists researching “the accurate determination of racial types” in South Africa die in an explosion. Kpoof! He called it The Invention and the Royal Court Theatre, where he worked as a play reader, staged it on a Sunday night in December 1959. On New Year’s Day 1960, he returned to Nigeria, where he began work on A Dance of the Forests.

He wrote that play in the grip of a startling finding. The nationalists, the first-generation of Nigerian leaders waiting to take over the semi-independent country, had begun to visit Britain in waves, and, to the shock of the African students there, displayed vulgar wealth and condescension towards their own people. In his memoir You Must Set Forth at Dawn, he describes being stranded in Paris and, being alerted by a French official, making a courtesy call to a man he presumed was Alhaji Tafawa Balewa, the incoming Prime Minister. Surrounding the quiet man were guards and associates whose rudeness shocked him and he left in anger. Only later did he learn that the man he met was not Balewa but his mentor Ahmadu Bello, the Sardauna of Sokoto and the real power in the country.

He and other students were realizing: these elite saw their continent not as a land in need of liberation but as “a prostrate victim to be ravished.” Embarrassingly, sex was high on the politicians’ list. They recruited students as pimps and lavished gifts on escorts. He recalled “a revered national figure in a highly sensitive political position” who gave a check to a White girl, who then came boasting to the African students that she had their national figure. They retrieved the check by playing on racial stereotypes, promising to introduce her to a “virile” boyfriend. Scandals roiled, all hushed by the British Home Office. These new leaders were re-establishing between themselves and their countrymen the exact master-servant dynamic between the Boers and the Black South African majority. “The pan-African project was becoming farcical,” he wrote.

In A Dance of the Forests, he staked truthful observation and challenge to authority as the final barrier to cultural breakdown, and he raised the role of the artist, placing him at the center of a societal malaise, as vessel and saboteur. It is easy to miss in the multi-pronged swirl of the play, but in art, the indicted tend to see themselves. Soyinka entered it for an Independence Celebration contest and it won, to his surprise. The officials had picked a play they did not read, picked him based on his rising reputation as a returnee. When they canned it on the eve of celebrations, he staged it in Ibadan instead, where his theatre group, The 1960 Masks, operated. He was touring the country, observing rituals, festivals, seasonal ceremonials, and, as he later put it, “worrying out dramatic forms from the mould.”

He got in his Land Rover and was in Benin City when a strange message reached him: would he produce and compere the gala evening at the installation of Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe as the new Governor-General? He was flattered; this was the great Zik of Africa — even as he and many Nigerians did not understand why “the father of the nation” was willing to transform into a ceremonial surrogate of the Queen of England. He drove back to Lagos. Where things got worse.

Madame Lilian Evanti, the famed American soprano, was performing at the party. He found her uncooperative and unprepared, and in a mishap in which he tried to move the pace of programming along while she still wanted to perform, the singer got annoyed. People demanded his firing on the spot. They’d heard about his nation-embarrassing play and determined that he was no good. They demanded he apologize to Zik, although it was not Zik but his associates who were offended. Soyinka had hoped that the Independence Celebrations would show his talents; instead, he gained a reputation for being stubborn and disrespectful to the most respected people in the country.

His parents were worried. “These are very powerful people,” his mother warned. “You have to be very careful.”

“These people you are dealing with, they are not the old colonial officers,” his father said.

“And the man you are worrying about, Zik, you think he is such a small-minded person?” Soyinka asked them.

“It’s not the people at the top you have to worry about,” they cautioned, “it is those around them, awon alagbejoro, the lackeys who only live to spoil the career of others.”

A staging of A Dance of the Forests, the play that made Soyinka his first political enemies. Credit: Tunde Awosanmi, A DANCE OF THE FORESTS, 2024, Zmirage Multimedia Open Door Series.

A staging of A Dance of the Forests, the play that made Soyinka his first political enemies. Credit: Tunde Awosanmi, A DANCE OF THE FORESTS, 2024, Zmirage Multimedia Open Door Series.

A staging of A Dance of the Forests, the play that made Soyinka his first political enemies. Credit: Tunde Awosanmi, A DANCE OF THE FORESTS, 2024, Zmirage Multimedia Open Door Series.

A staging of A Dance of the Forests, the play that made Soyinka his first political enemies. Credit: Tunde Awosanmi, A DANCE OF THE FORESTS, 2024, Zmirage Multimedia Open Door Series.

Before his continental recognition as a playwright of note, Soyinka was asserting himself as a razor-sharp critic, taking positions that cemented him as the enfant terrible of African literature. His first essay, likely written in Leeds but published on his return in 1960, appeared in The Horn, the poetry magazine of the University of Ibadan, founded by J.P. Clark and Martin Banham. The title was a swinging declaration, “The Future of African Writing,” and his argument rended convention: Early African writing lacked honesty because it pandered to the European eye; it would lack authenticity until it replaced racial self-assertion with indifferent self-acceptance. He held two writers as representative of the dilemma:

The significance of Chinua Achebe is the evolvement, in West African writing, of the seemingly indifferent acceptance. And this, I believe, is the turning point in our literary development. It is also a fortunate accident of timing, because of the inherently invalid doctrine of “negritude.” Leopold Senghor, to name a blatant example. And if we would speak of “negritude” in a more acceptable broader sense, Chinua Achebe is a more “African” writer than Senghor. The duiker will not paint “duiker” on his beautiful back to proclaim his duikeritude; you’ll know him by his elegant leap. The less self-conscious the African is, and the more innately his individual qualities appear in his writing, the more seriously he will be taken as an artist of exciting dignity. . . . Senghor seems to be so artistically expatriate . . . [and poets like him] are a definite retrogressive pseudo-romantic influence on a healthy development of West African writing.

That essay set the stage for the nexus event of June 1962 at Makerere University, Kampala. The Conference of African Writers of English Expression was a gathering of writers under 35, who had come to the same realization that gaining independence opened a new battlefront. Their task: to discuss the problems of their art and time and define what was taking shape as “African literature.”

It was not a truly continental gathering. There were East Africans: Grace Ogot, John Nagenda, Rebecca Njau. But there were more Nigerians: Soyinka, Achebe, Clark, Christopher Okigbo, Gabriel Okara, Donatus Nwoga; and Ghanaians: George Awooner-Williams, Elizabeth Spio-Garbrah, Cameron Duodu; and South Africans in exile: Ezekiel Mphahlele, Bloke Modisane, Arthur Maimane. They invited as observers a handful of publishers, editors, journalists, and Francophone African and Black American writers. They descended on campus in jumpers, dashikis, and agbadas, in sandals and with beards, and in that informal camaraderie, over long sessions of academic papers and readings of new writing, tore into opinions and trends with blunt earnestness.

They tabled everything: English- and French-speaking African writing, West Indian writing, Negro American writing; the states of the novel, the short story, drama, poetry, even translation; the varied “vernacular” that their conference excluded but in which indigenous literature flourished: Yoruba, Swahili, Sotho, with rhythms that no translation could capture. They understood their colonial divides: the continent’s leading English-writers were educated at home and the French-writers abroad.

They engaged the matrix of language and culture: Since no foreign tongue could express the Africanness of thought and feeling in indigenous languages, should they invent a new style? As much of Black and African writing were literatures of protest, was that subject matter limiting the essence of creative writing? And if language wasn’t the determiner of Africanness, what was? Authorial origin? Theme? Okigbo decried a purely racial line: writing was African if rooted in African experiences and feeling, and an actual African could lack that authenticity. Langston Hughes argued that authorship and theme were in themselves sources of Africanness. Bernard Fonlon said it was point of view: he’d listened to a West Indian band in Paris and knew from his style that the guitarist was Cameroonian.

They noted the necessity of Negro critics assessing books before publication, because White readers tended to condescend and praise books of little value simply because the author was African. Achebe said his novels were sometimes praised for the wrong reasons. They agreed to not pander to Western tastes and disagreed on the extent of the depiction of sex. Soon the conversation converged on a central issue: How would they gain an audience in Africa itself? It was then that Okigbo uttered those famous lines: “I write my poetry for poets only!” The conference was confounded. Soyinka, already leaning away from the utilitarians, agreed.

Negritude was raised and the atmosphere strained. Mphahlele held that, because Black South Africans were fighting for their human dignity and not for their Blackness as some Black people were, Negritude as a literary expression would manifest differently, writer to writer, and so ought not be viewed as the solution for all African issues. It may have been then that Soyinka refashioned his duiker and duikeritude line for the Negritude crowd: “The tiger does not pronounce its tigritude,” he cautioned. “It pounces!”

The Makerere sessions, he would write years later, were “truly ruthless, often wrongheaded,” a “total rejection of all substandards, of pastiche and stereotype. . . The irreverence, the impatience. . . was the most memorable aspect.”

He was entering a long era of angst, of traveling and furious noting, and nothing escaped his spite, not even buildings. Visiting the National Theatre in Kampala, he was disappointed to find an uninspiring structure that reminded him of the even worse designed, unventilated, un-soundproofed one in Ibadan. He put that in a punchy, humorous essay titled “Towards a True Theatre.” In four pages, he lined up the expensive architectural failures of theatre buildings — “abortions . . . offensive to the eye and repressive of the imagination . . . For we are not merely talking about structure now, but of the dubious art to which it must give birth.”

That essay had no sooner appeared in December 1962 when he followed it with two unsparing claps. European critics were, when reviewing African writing, “brainwashed . . . of existing standards . . . a deliberate mental retardation,” he wrote in “From a Common Blackcloth: A Reassessment of the African Literary Image.” And their condescension was abetted by African writers. Why else would Camara Laye go from the “air of magic” of The Dark Child to the “obvious imitativeness” of his Kafkian The Radiance of the King? How else would a “fumbling first novel” by Onuora Nzekwu be praised as “very successful”? Peter Abrahams, Alan Paton, and William Conton, he argued, “fail at the altar of humanity because they have not written of the African from the dignity and authority of self-acceptance”:

Only through the confidence of individual art, like the early Amos Tutuola, through the hurtful realism of Alex la Guma, the sincerity of Chinua Achebe and the total defiant self-acceptance of Mongo Beti, can the African emerge as a creature of sensibilities.

The task was to be African in opposition to European, to confront the Western world with something more solid than what was in its books. Creativity was a decolonizing weapon, and to extricate themselves from denigration, their writings had to be combative. It explained why Negritude, for what he deemed its failure in radical self-acceptance and indulgence in self-worship, became an African casualty of his fury. His brutal takedown of Senghor peaked in a 1963 essay with a harsh title: “And After the Narcissist?” Negritude, with its defanging of poetry’s ability to aggravate, was in a stasis: no action, only narcissism, a new limitation imposed on African writing.

Those battles with Negritude may have influenced his eventual aversion to “literary ideology.” Though, years later, as he came to terms with his own intellectual heat, he would come to believe that he went too far in his excoriation and would pull the essay from a collection of his work. In the introduction to that book, Art, Dialogue and Outrage: Essays on Literature and Culture, the critic Biodun Jeyifo estimates that Soyinka undertook “the most comprehensive review of writers and the entire literary scene that we may yet encounter in contemporary African literary discourse, viewed from the vantage point of one writer on other writers.”

If Soyinka took Makerere as a physical outlet and the essays as a bulwark against retrogressive literary attitudes, the source of his impatience was worsening back home. Western Nigeria had become the first of the three regions to unravel, and a state of emergency had been declared. Samuel Ladoke Akintola’s Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP), which broke away from Obafemi Awolowo’s socialism-sympathetic Action Group (AG) and spearheaded ethnic hatred of the Igbo, ran the Government of the West and a reign of terror.

Convinced, erroneously, that academia was the barrier to controlling public perception, Akintola turned the newly created University of Ife into an ethnic stronghold of Yoruba loyalists. It was in response to an earlier scandal at the University of Ibadan, where a medical fraud was imposed as Chairman of the University Council. The man was Igbo and the directive came from Governor-General Azikiwe, an Igbo, and as the university capitulated, the perception formed that it was an ethnic takeover. At the time, in December 1961, Soyinka had resigned from his Research Fellow in Drama position and withdrew his work from the university press. He moved to the University of Ife, which was then down the road, taking precaution to live off-campus, in an empty government building, distanced from academic politics. From there, he edited Black Orpheus, a publication whose European name he disliked. Now with the new school declaring a Credo in support of Akintola’s government, some staff resigned in protest. For the second time, Soyinka resigned a university job. But he kept the building.

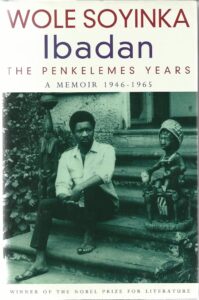

Exhausted, he got in his Land Rover, to go to Cotonou, but was stopped at the border by the secret police. “It was a strange, unsettling feeling,” he recalled later in his illeist memoir Ibadan: The Penkelemes Years. “This was his own country, the space of earth in which he was spawned, and now he was learning, at the very late age of twenty-eight, that it was his prison.” The officials barged into the wagon, pulling out the seats and carpets, emptying his luggage of papers. The sheets were plays in progress, but the officials imagined it was a secret list.

“Who is Eman?” one asked, holding a page of The Strong Breed. “Who is Danlola?” another pointed at Kongi’s Harvest. One raised Alexander Pope’s The Dunciad. “What is this one, oga?”

“Poetry.”

“Poetry? What kind is that, sir?”

“Satirical poetry.”

“What I am asking, sir, is, what does it mean?”

“I don’t give free lectures. If you want a course in poetry, it shouldn’t be too difficult for your Department to track me down. Then we can discuss terms.”

They detained the book.

It was 1963. His creative life in Ibadan revolved around Orisun Theatre, the dramatic company he founded to replace The 1960 Masks and ran from his government building home, and the Mbari Artists’ and Writers’ Club in Adamasimgba, an offshoot of the Igbo arts group and a hangout for some of the city’s finest minds and visiting writers — Okigbo, Ezekiel Mphahlele, J.P. Clark, Frances Ademola — with whom he argued literature and politics. He was at work on his first novel The Interpreters, and that period of steroidal dialogue fed its story of five returnees — a physician, a journalist, an engineer, a teacher, and an artist — conversing about their homeland. The following year, as he turned 30, Oxford University Press published his 5 Plays, bundling together A Dance of the Forests, the religious satire The Trials of Brother Jero, the philosophical The Strong Breed and The Swamp Dwellers, and the comedy The Lion and the Jewel, the last two of which he wrote in London.

The characters in The Swamp Dwellers are waking up to realizations: that the young want something different from the aged, that blood was no thicker than the flood in their land, and that, in their time of need, the gods have deserted them. The action takes place in the home of a cantankerous couple, husband Makuri and wife Alu, who are visited by a knowing blind Beggar and often by the dubious priest Kadiye, and, after years of hoping, by their angry son Igwezu, whose return is greeted by the flooding of his farm. The several conflicts narrow down to Igwezu and Kadiye. Igwezu wants answers. The accusations, quarrels, debates, and threats escalate in the play’s single setting: a room in a hut on stilts, with walls of marsh stakes plaited with hemp ropes, built on a semi-firm island in the swamps, noised by frogs and rain. The Swamp Dwellers required a more elaborate stage construction and morose atmosphere than The Lion and the Jewel, the tale of schoolteacher Lakunle’s longing for village belle Sidi, which peaks with rich dances and a most rowdy set.

But into Orisun Theatre, politics intruded. Hearing that the police planned to invade it, he taught his boys how to defend themselves, with a fire extinguisher. One night, the police arrived. Whatever they expected, he planned differently. He pulled out a machine gun and began shooting as they ran. They drove off and he drove after them, chasing them around the city suburbs.

The situation in Western Nigeria was about to engulf the region when Soyinka did something audacious that put him in the national lore. The alliance between the Northern Peoples’ Congress (NPC), which held Federal power, and the National Council of Nigerian Citizens (NCNC) broke down. The NPC strengthened its alliance with the NNDP in the West, under the name of Nigerian National Alliance, but which many saw as merely a Nigerian Northern Alliance. The NCNC allied with the Action Group (AG) under the name United Progressive Grand Alliance (UPGA). The Yoruba leader Awolowo was thrown in prison in Calabar, on charges of conspiracy to overthrow the government. Alleging rigging in the West, North, and capital territory of Lagos, UPGA boycotted the 1964 elections in the East. A nationwide labour strike was quelled through bribery.

The West, wealthy in cocoa and boasting a free primary education, was wasting away. Farmers rose in revolt and with Dane guns broke out of prison their peers in Ondo and Ilesha. The Army, even after requests by the Federal Government, refused to attack citizens; but sections of it armed and trained NNDP thugs. The police, meanwhile, were shooting up schools and markets, carting away families of insurgents as hostages, torching villages and crops. The robbed wealth showed up in the new American cars of politicians, in mortgages to Indian, Greek, and Lebanese merchants, in the privately owned skyscrapers.

Corruption was so widespread that people converted Premier S.L. Akintola’s initials S.L. to “Ese-Ole,” Yoruba for Feet of a Robber, and the High Life singer Victor Olaiya put out a song called “Omilegogoro” — Yoruba for Owner of the House of Heights — about the private skyscrapers. The NNDP introduced a term “National Cake”; the Deputy Premier, Chief Fani-Kayode, declared, “They call us the Chop-Chop Party. So? Who doesn’t want to chop? I want to chop. . . Those who want to chop, come over to our side.” It was a different Nigeria then, and the country still held enough values to be shocked. But when Chief Fani-Kayode said on the radio, “Who needs the people to vote for us? The angels in heaven have already cast their votes for our party!” the people heard it as an intent to rig their votes. Elections began, and as commandeered Western Region radios announced false results for the NNDP, the Premier of the East, Michael Okpara, smuggled in a radio transmitter to broadcast the real results.

Soyinka was now a senior lecturer at the University of Lagos, and he and other resignees from Ife now called themselves the Credo Group, after the NNDP’s Credo to take over the school. When the journalist Kaye Whiteman, of the London-based West Africa, casually mentioned that the secret transmitter was in Awolowo’s house, the Credo Group laid a plan.

Soyinka arrived the house and a young UPGA candidate named Soji Odunjo told him how he obtained his own winner’s certificate: he’d pressed a gun to the electoral officer’s head. Soji Odunjo left and Soyinka stepped into the toilet, overcome by a sense of the asinine. He had come with a gun, and now he knew what to do. The leader of the Eastern news group was a comedian named Ukonu, and he told Soyinka that they were leaving for the East before NNDP thugs got there.

“Ukonu, I’m afraid we can’t let you go just yet,” Soyinka said. “You are under arrest until you’ve broadcast every last result of this election.” There was something else he wanted broadcast: “A call for a general uprising in the West.”

Ukonu, surprised, was determined to leave. “You, man?”

Soyinka pulled out his gun. “You have a choice.”

“That’s a real gun!”

“It’s a real fight, Ukonu.”

Ukonu grinned. “Brother, I am with you. I am under voluntary arrest.”

He wrote the statements for Ukonu to continue broadcasting when he reached the East. The next Saturday, hanging out in the home of his friend Femi Johnson, he learned that Premier Akintola would make a broadcast that evening, likely pre-tapped. It was a golden chance, and he wished he hadn’t given Ukonu his written statements. One way or another, the Premier’s broadcast must be stopped. From Orisun Theatre, he picked a young actor named Jimi Solanke to drive him to the Broadcasting House. In the studio, readying the Premier’s tape for broadcast, were some of the newsmen he’d met and threatened in Awolowo’s house. It looked like a joke, a bad rehearsal of a farce. But they knew he wasn’t joking. They stepped aside. He replaced the tapes. When the appointed time came for the people of the Western Nigeria to hear more of their Premier’s aggression, they heard something strange but pleasurable:

This is the voice of the people, the true people of this nation. And they are telling you, Akintola, get out! Get out and take with you your renegades who have lost all sense of shame . . . .

By the time another duty officer took the tape off air, Soyinka was already in the car with Solanke. By dawn, he was on his way to the East, to seek refuge in Nsukka, and to meet the region’s Premier, Michael Okpara.

Later, he turned himself in and was detained in Ibadan that October. His parents visited. Okigbo visited with palm wine and poetry, which they read aloud, because Okigbo loved to listen to his poems speak to him. But Soyinka could see that it was a different Okigbo: he was remote, detached, started to say things but drifted off. From America, writers including Norman Mailer, William Styron, and Alfred Kazin appealed to the Nigerian government for his safety. Soyinka got a Christmas card from the Credo Group, which now fronted as the Committee of Writers for Individual Liberty (CWIL). A poem:

Playing Christ is a historic art . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Lifts a man to heavenly glory . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . All but he (Saviour Self-Elect)

Can hear the broken bells about his neck, loud

In warning of the approach of the abomination.

Early the next month, on January 15, 1966, the Army struck. The first military coup took out Premier Akintola of the West, Premier Ahmadu Bello of the North, Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa, and a host of top military officials. The coup leaders were Southerners and mostly Easterners, Igbo, and the casualties were mostly Northerners, because it was mostly Northerners in power. It was the first step to war.

Out of his three-month detention, Soyinka was invigorated. But the coup had changed the country.

At first, the North wanted secession. But in May, Northerners rose in reprisal killings, massacring their Eastern and Igbo neighbours, torching their homes and businesses. The Igbo fled to the East, then were encouraged to return. It was a trap. In July, Northern soldiers executed a countercoup, targeting Southern and Igbo political and military leaders, including the new head of state General Aguiyi-Ironsi and the Western Region governor Lieutenant-Colonel Adekunle Fajuyi. The countercoup, led by a Muslim Fulani lieutenant-colonel named Murtala Mohammed, brought to power Yakubu Gowon, a Christian from the minority Ngas ethnic group that was nevertheless part of the Core North superstructure. Gowon’s chess move was to release the Yoruba leader Awolowo from prison, appeasing the West.

In October and November, an even wider pogrom of the Igbo erupted, not just in the North but now also in the West. Roadblocks were set up to identify Igbo people, and Soyinka’s wife Olaide lent Yoruba clothing to Igbo neighbours, for disguise. Survivors fled East, in trains loaded with mutilated bodies. Estimates put the dead at 30,000. The continued genocide of the Igbo was the final straw, and Lieutenant-Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu, the military governor of the East and de facto leader of the Igbo, called for his people to return en masse to the East. At the Aburi Accords in Ghana, he pressed demands, which Gowon agreed to. But back in Nigeria, Northern politicians pressured Gowon to relent. The British backed Gowon; they would support a military regime as long as it was led by the North.

Soyinka, who had been writing articles denouncing the genocide, went to see Awolowo, who was expected to be offered a place in Gowon’s government. “Suppose you decide to decline the offer; you realize your life may be in danger?” he asked Awolowo.

“Yes,” the Yoruba Leader said. “But I’ve always insisted that my first duty is to the Yoruba nation. And I put that nation first, then the one called Nigeria.”

Soyinka offered to smuggle him out of the country.

“I have not led Yoruba people so far as to have our land turned into a battleground,” Awolowo replied, and then revealed that Ojukwu privately informed him that the East had decided to secede. “I said to Ojukwu, ‘At least let us in the West have a minimum of two weeks’ notice before you announce.’”

“Why two weeks?” Soyinka asked.

Awolowo would not say.

On May 30, 1967, Ojukwu declared the secession of the former Eastern Region as Biafra. Shortly after, Awolowo accepted Gowon’s offer to be his Minister of Finance. The West had allied with the North against the East. Soyinka sought a rationale: the countercoup ensured that the military was dominated by the North and the Middle Belt, leaving the West with no bargaining power.

Those final weeks of peace was when Soyinka traveled to Sweden, for the Afro-Scandinavian Writers’ Conference. His address, titled “The Writer in a Modern African State,” was a lashing. Writers had become irrelevant because they crystallized their image “in the character of the Establishment,” he fumed:

When the writer woke from his opium dream of metaphysical abstractions, he found that the politician used his absence. . . to consolidate his position. . . the writer, who in any case belonged to the same or a superior, intellectual class, rationalized the situation and refused to deny himself the rewards of joining others in safety. . . The artist has always functioned in African society as the record of the mores and experience of his society and the voice of vision. . . It is time for him to respond to this essence.

But as he spoke, his fury felt futile. The coup, countercoup, pogrom, and secession splintered a Nigerian literary scene that had never been close. He and J.P. Clark were close to Okigbo, and now Okigbo, Achebe, Gabriel Okara, and Cyprian Ekwensi were in Biafra, and Clark, Mabel Segun, and Amos Tutuola were on the Federal side. The newly Biafran writers skipped the conference. Soyinka did not want secession because Biafra could not defend itself against British-backed Nigeria; it was a just cause but also, as he saw it, “simply politically and militarily unwise.” The decision of the Biafran writers to not attend the Stockholm Conference — how could they, recovering from genocide and with an invasion on their hands? — was why Soyinka undertook the dangerous expedition into Biafra, to seek peace, which landed him in prison for most of the coming war.

They came to be called the Third Force: the group of elite organizers who, in 1967, caught between the thesis of Nigeria and the antithesis of Biafra, sought a synthesis that opposed war and prepared to mobilize against it. The Igbo had been struck by rejection and isolation, and someone had to go to the East and meet not only its head of government Ojukwu but also Achebe and the new nation’s intellectuals.

“Madness, nothing but madness!” his friend Femi Johnson, who hosted the naming of the group, told him. “You’ll get shot for nothing.”

In Onitsha, vigilantes arrested him, sent him to a cell in Enugu, where a superior recognized him and scolded his subordinates. Coincidentally, Okigbo arrived to collect reinforcements. The poet was, Soyinka recalls in You Must Set Forth at Dawn, “kitted for war — in casual civilian clothing, but complete with rifle and ammunition belt. . . the excitation of battle still fresh in his eyes. For one brief, nostalgic moment, I believe I envied this friend and colleague who would rather be a poet but had thrown himself fully into a self-defining cause.” It saddened Soyinka: they expected that the first war of their generation would be in South Africa, against Apartheid; now it was in their own country. Seeing him, Okigbo let out a screech and lapsed into a dance. They promised to meet later that evening. They did not. Okigbo died in Okigwe. Soyinka heard that among his final words were “¡No pasarán!” As chanted by anti-fascists during the Spanish Civil War. They shall not pass!

Soyinka knew Ojukwu from their circles in Yaba, when the two young men dated a pair of sisters, and Soyinka envied the millionaire heir’s jazzy sports car. Meeting now, as national defender and international mediator, they ate akara and exchanged viewpoints and upper-class British accents. Ojukwu told him that it was the people’s decision to secede, that he speak to civilian leaders. Soyinka met, too, with Wole Ademoyega and Victor Banjo, two Yoruba military men who were involved in the first “Igbo” coup. Banjo, a detribalized man, determined that Nigeria needed liberation from Northern domination, and told Soyinka to pass a message to Awolowo:

Let them understand in the West that I am not leading a Biafran army but an army of liberation, made up not only of Biafrans but of other ethnic groups. Urge them not to be taken in by any propaganda by the federal government about a Biafran plan to subjugate the rest of the nation, especially the West.

Soyinka conveyed Banjo’s message to Yoruba civilian leaders except Awolowo. “After my meeting with that politician,” he wrote about Awolowo in You Must Set Forth at Dawn, “I simply felt, intuitively, that the approaching conflict was not one in which he should be involved.”

Three days after Soyinka left, Banjo led the Biafran invasion of the neutral Midwest. As the West itself waited in confusion for its leaders to provide guidance, Soyinka rang the new governor, Olusegun Obasanjo, through a secret telephone in the lieutenant-colonel’s room, which the military man did not know existed. He was in contact with Obasanjo’s junior officers, who resented Northern domination in the army, sympathized with the Biafrans, and told him to not trust Obasanjo. They met as agreed, “unarmed and unaccompanied.”

Accounts differ of that meeting. Soyinka told Obasanjo that Banjo was an anti-secessionist who was secretly working to stop the war, that Banjo wanted Western leaders to let him take control of Lagos and thwart both Gowon’s and Ojukwu’s plans. Soyinka has written that, while he believed “that Banjo represented the most viable corrective,” he did not pressure Obasanjo. He wrote that Obasanjo replied that his loyalty was to Lagos, and whoever gained Lagos gained his loyalty, but until then, he would not let the Biafran Army pass through the West to take Lagos. But to his superiors, and later in his 1980 memoir My Command, Obasanjo claimed that Soyinka tried to bribe him to obtain passage for the Biafran Army. A month after the start of war, Soyinka was thrown in prison, on false charges of negotiating to buy warplanes for Biafra.

By then, Banjo had announced the secession of the Midwest, but his delay there, rather than invade an already anti-Federal Western Region, gave the Federal Government ample time to move from a tempo of “police action” to “total war,” laying on the table all options, including blockade, starvation, and outright massacres of surrendered citizens. The deaths of three million Easterners and thousands of Midwesterners were imminent. Had Banjo made his move, had the West welcomed him with a popular uprising planned by the Third Force, Nigerian history might have been different.

And he, Soyinka, might not have spent 26 months tormented in Kaduna Prison, with his wife Olaide appealing for intervention. He might not have spent two-thirds of his lifetime dueling with successive regimes. The country may have averted the wrath of Abacha, and he might not have been forced to get on that motorcycle and flee the country. He would not return until after the death of Abacha. The following year, 1999, Nigeria returned to democracy.

IV.

The Stage

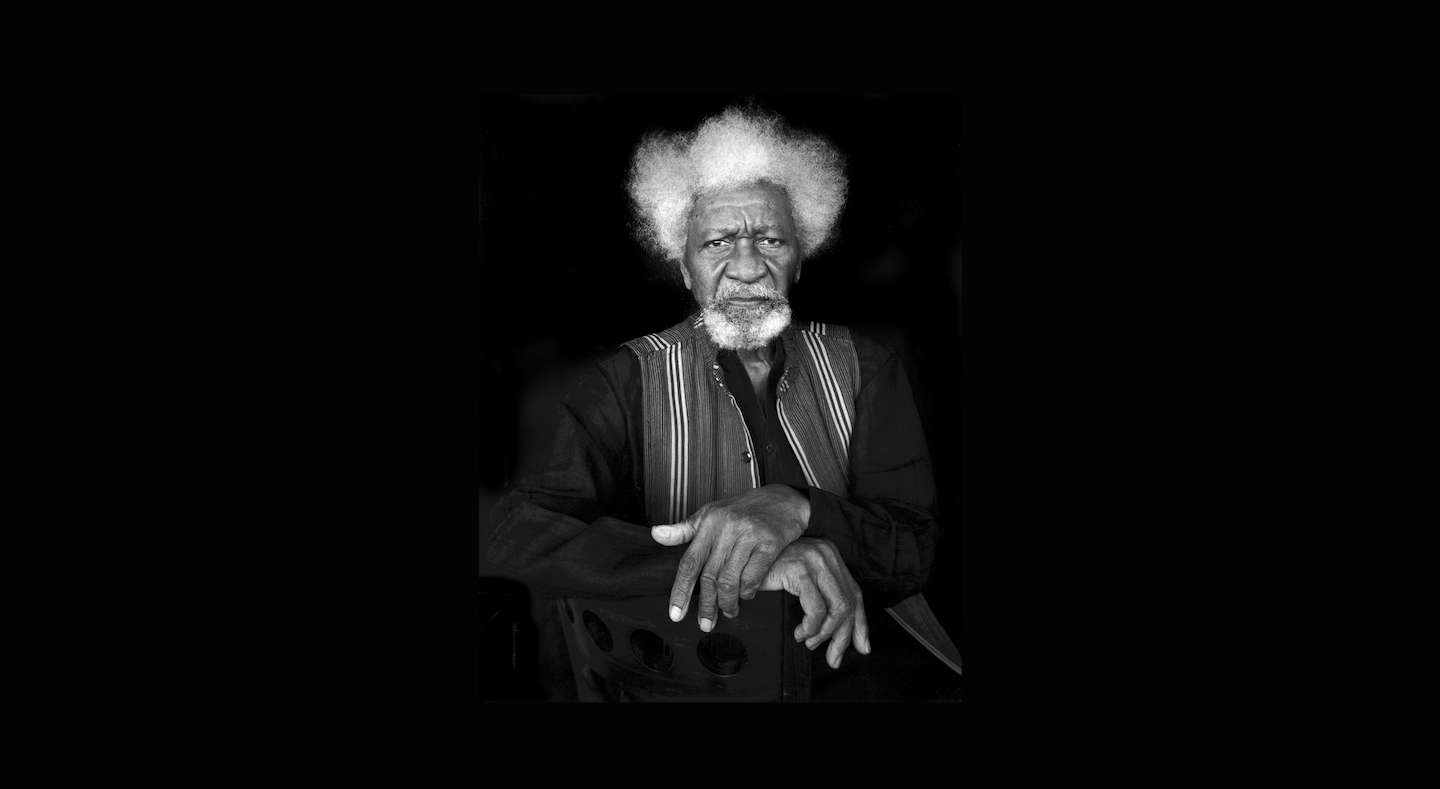

I met Soyinka in Chicago, at the peak of summer, amid his cross-continental tour. It was a July morning, the air stagnant with heat. A month before, Ngugi wa Thiong’o had passed on, twelve years after Chinua Achebe did, leaving Soyinka as the last standing member of the great triumvirate of African literature. Then the day before our interview, Muhammadu Buhari died; a man who as military head of state decreed, in Soyinka’s words, “the very word ‘democracy’ criminalized,” but as a clueless, cruel civilian president haunted him for what was widely believed to be the writer’s tacit endorsement of his campaign. His peers, literary and political, were leaving the stage, leaving him with, perhaps, more disenfranchised isolation than he understated in his memoirs.

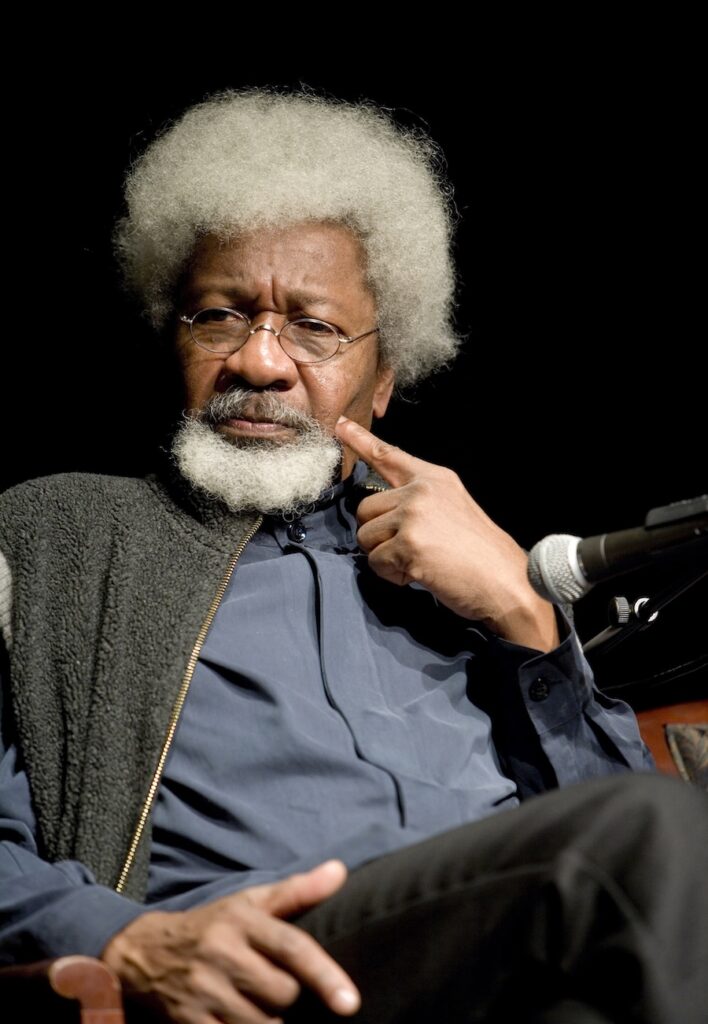

It was in the shadow of these terminal events that I pulled up on a leafy street in the University of Chicago and waited in the hotel lobby. I watched the entrance and exit, expecting a retinue, so that when he finally walked up to the reception, tote bag on shoulder, I was taken unawares. There he was, the greatest living writer, that famed crown of white afro and beard, and he was alone, shorn of ceremony.

I threw myself on the floor, in the traditional Yoruba male greeting, then got up and did the Igbo bow. “Papa.”

“Ah. You.” I may have misheard. He shook my hand.

I first sought this interview four years ago, and he was open to it, acknowledging and warm; when I reached out directly, he told me that people often sent him Open Country Mag pieces, that they were “always a scintillating read.” But he was traveling then and schedules misaligned. And then in June, the day news came of Ngugi’s passing, I asked after a three-year gap and he gave a genial but firm no. Interviews took time, he said, and time was something he did not have. But when I replied to thank him two days later, he suddenly said yes: he had looked at our correspondence over the years and now wanted to.

But not right now. I was early and he still had his first event of the day to attend.

“Make yourself comfortable,” he gestured around the lobby. “There’s wine. There’s food.”

I watched his back, the last of the literary lions, and settled into the sofa wondering about his English voices, the clarity of his speaking and the complexity of his writing. (I’d read that his Yoruba idiolect is mellifluous.) In person, his words are straightforward, immediate, clad in that British-ed Nigerian accent. But on paper, in his nonfiction, the prose meanders like the rolling African realms it traces: from page to page, seemingly settled conclusions cave in and from the rupture he extends finer, subtler claims and caveats, like a geometric sequence. His essays must be read in full to locate his locus, and his ideas are too nuanced to be approximated, too intricate to be summarized. It is a particular difficulty of reading him, which is why more people have read about him than have read him, which is why his indigenizing bequest in our approach to art and literature is still not fully understood.

In his work, time is a deciding factor, the cyclic reality of primordial time, which requires a human medium. Within it, we engage the world, unlock sub-worlds of Ritual, participate in art — and reading him becomes a dance of exposition, a ritual whose spiritual benefits would not be obtained until the final flute. In this meddle of time, rituals, and creation, this “drama of the gods,” the Yoruba pantheon and cosmic totality are his cruces of fascination, and he casts himself as an inheritor of that tradition of ritual theatre: a chthonic crossing through the four realms of African metaphysics — the worlds of the ancestors, the living, the unborn, and the dark continuum — “a cleansing, binding, communal, recreative force” out of which serious art emerges.

The patakis, the Yoruba myths of old, hold the orishas as the final extent of eternity, but in Soyinka’s first standalone mapping of that inexhaustible metaphysical world, with “The Fourth Stage: Through the Mysteries of Ogun to the Origin of Yoruba Tragedy,” he argued that the Yoruba mind does not seek “absorption in godlike essence,” but instead recognizes itself as a vital conduit for the coexistence of the past, present, and future. It is humanity’s awareness of its “primal severance” from other areas of existence — the ancestors and the unborn — that led it to institute rituals and myths to close that cosmic gulf. The orishas, too, were severed from “transient awareness,” and when they first descended to earth to reunite with human essence and found a chaotic jungle in their way, it was Ogun who led with his iron blade and felled the forest. By leading the gods across the gulf, he became conqueror of the fourth stage of existence, that realm of transition between the rest, and a “harmonious Yoruba world” was born. Ogun did not only dare the transition; he bridged it with knowledge, creativity, and art; and there in that fourth stage, in the “titanic” will to transcend suffering in the abyss of god and man, came the birth of tragedy.

His premise grew with Myth, Literature and the African World, his foundational treatise from 1976, in which he views Ogun, Sango, and Obatala as most adaptable to the ritualistic demands of drama as an art form. In varying literary versions of their myths, the trio are fallible. Their hubris or inertia disrupts the balance and continuity of cosmic regulation, triggering “compensating energies.”

Obatala, whose failing is his drinking, comes upon blood and moulds man and becomes the god of creation and soul purity. Sango, born as a man, watches injustice and challenges the Supreme God Olodumare, is rebuked by Obatala, and, to complete equity in his ego, takes his own life and ascends as god of lightning and justice. Disguised as a traveler in Sango’s kingdom, Obatala is imprisoned, accused of theft. The disappearance of the god of creation frees a plague. It frees, also, the other half of the creative-destructive principle: the rigid, restorative balance of Ogun, god of rebirth and destruction, of iron and art. The two halves do not usurp each other: where Obatala is “the functionalist of creation,” Ogun is “the essence of creativity itself.”

Within artistic drama, the passage-rites of the gods project man’s tussle to harness his physical, social, and psychic environment, and the deities become the “intermediary quester” and “explorer into territories of ‘essence-ideal’ around whose edges man fearfully skirts.” Being “a prefiguration of conscious being,” the deities “enhance man’s existence within the cyclic consciousness of time.” It is inside this system that traditional society tasks itself with social questions and moralities. It is this structure that, he writes, shapes “the aesthetic considerations of ritual enactment and give to every performance a multi-level experience of the mystical and the mundane.”

In this deistical drama, serious music and poetry manifests as the spectacle of the community itself, a vortex of its history, moralities, and supplications. Casual art, secular entertainment, on the other hand, may involve the deities but is not preoccupied with “creating the emotional and spiritual overtones that would pervade. . . the consecrated spot where the divine presence must be invoked and borne within the actor-surrogate.” That ritualist mould of a play is “where all action and all personae reach deeply through the reserves of the collective memory of human rites of passage — ordeal, survival, social and individual purgation — into an end result which is the moral code of society.” And tragic feeling arises from a grasp of “the protagonist’s foray into this psychic abyss of recreative energies.”

But as Soyinka toured the country, observing staging after staging of plays, he became convinced that most serious-presenting art had drifted from their sources, that the typical producer had become an “enthusiastic promoter” rather than “a truly communicant medium in what is essentially a ‘rite of passage.’” As more rituals moved from their “charged spaces” of origin or natural habitat of the shrine to public festivals, as “the emotive progression which leads to communal ecstasy or catharsis [got] destroyed in the process of re-staging,” the artists revealed themselves to lack the imagination needed to communicate the physical space of staging as “a manageable contraction of the cosmic envelope” within which man must “survive confrontation with forces,” internalize them, and implode to achieve a titanic scale of passion.

The artist achieves cohesive interiority when he understands ritual theatre as a battleground of forces greater than petty human norms, where even lesser characters are “protagonists of continuity.” He saw this in the Ori-Olokun Theatre in Ife and Duro Ladipo’s company, and watching Ladipo’s Oba Koso, he thought: Here is perfect unity rarely encountered on the modern African stage.

Soyinka began writing Myth, Literature and the African World in 1973. The Biafran War had ended three years before, and General Gowon was pursuing an economics of attrition against the Igbo. Unable to assume a position at the University of Ife, he went to Cambridge University on a fellowship. A student, working on mythopoeia in Black literatures, could not get his subject approved because the Department of English did not believe that there could be African literature. Soyinka was stunned. Sheffield University, where he was a visiting professor, had a full African Literature program, but Cambridge did not even believe it existed, much less was worthy of study. He stepped in to supervise the student. Back home, in the continental academia, an anti-colonial reverse had taken effect. Universities were substituting Departments of Literature for Departments of English, some shuttling African Literature into African Studies. It was, he wrote, “the apprehension of a culture whose reference points are taken from the culture itself.”

It is a book in which he separates the animators of African and European artistic worldviews. For all the parallels and claims of derivation between the Yoruba and Greek pantheons, he points out that, unlike in the balanced worldview of the former, the ethical concepts of the latter, as developed through the pessimistic line of Aeschylus to Shakespeare, lacked “a morality of reparations” — which is why their gods can exact unprovoked aggression on human beings and go unpunished, unless that aggression encroached on the terrains of a greater god.

Yet the urgent divergence is not in style or form or that African communal creativity clashes with European creative individualism. It is in how the former’s cultural artifacts “are evidence of a cohesive understanding of irreducible truths” where the latter’s creative impulses “are directed by period dialectics.” Where Western dramatic criticism bounds human anguish to time and place, African dramatic criticism takes for granted that individual infractions transcend their causes because they reflect “a far greater disharmony in the communal psyche.” What the European deems “fantasy,” the African sees as communicant primal reality; although as tragic art evolved towards specific events, its cosmic scope shrank and its morality became “a mere extraction of the intellect, separated from the total processes of being and human continuity.”

If the drama of the gods provides a template for society, and art originates from ritualizing those problems, then revolutionary writing, he argues, required not ideology but social vision. Such literature, ideal for the African, does not merely reflect experience; it reaches past basic narrative to “reveal realities beyond the immediately attainable”; it uncovers mental conditioning and, projecting a future, seeks to “free society of historical or other superstitions.” The key is self-caution without pandering.

There was certainly no pandering during Soyinka’s own peak dramatic run, a two-decade stretch from the late 1950s to the mid ‘70s, which — in addition to The Swamp Dwellers, The Lion and the Jewel, A Dance of the Forests, and The Trials of Brother Jero — also produced the absurdist Madmen and Specialists, the evangelical comedy sequel Jero’s Metamorphosis, and the political satire Kongi’s Harvest. The three are alert to the lapsing character of Nigeria, the shift of charlatans into a national cavity once filled by the awareness of self-will. But it is in another trio — The Strong Breed, The Road, and Death and the King’s Horseman — that he best reaches that cohesive interiority in which cosmic balance rights itself.

Eman, the stranger at the heart of The Strong Breed, is another schoolteacher, brave of mind and hard of head. The villagers must select a carrier for the new season, to expatiate the sins of the old, and their sights are set on Ifada, the community idiot, a nonverbal autistic. Unlike in The Swamp Dwellers, where Igwezu verbally challenges the gods’ adherence to the presumed benevolence of cosmic totality, The Strong Breed puts the opposer Eman in a direct interruption of a ritualistic process. Already a stranger in a land unwelcoming to strangers, he undertakes something he does not understand, to corrosive cost.

Soyinka’s intellectuals are sometimes caught between forces of emotion — and carved up. They do not have to initiate or oppose the ritualistic process itself, as Olunde, the medical doctor in Death and the King’s Horseman, realizes. When his father Elesin fails to undertake the ritualistic suicide to accompany the Oba’s burial, Olunde, just returned from Europe with his own dreams, must fill that gap in the cosmos. His chef-d’œuvre, it is Soyinka in sublime, sustained intensity, plumbing the lopsided ironies of a dissonant psyche. He took the seed of that trilemma from a historical event, involving a Yoruba chief and a British officer, earlier dramatized by Duro Ladipo in Oba Waja. The play, as most works of their generation, was read as a “clash between cultures,” forcing Soyinka to provide a critical guardrail: the point of the play is that, to progress a continent disrobed of its indigenous customs, the new way must meld with the old. Generations of understanding must collide.

Three hours passed before Soyinka returned, earlier than expected, and we sat in a corner, elevator doors sliding and shutting; the hotel lobby: busier, guests entering, leaving; outside, the sun rained down on the leafy campus. He was telling me about his photographic memory, and my mind went to 1962, when he lost the only manuscript of The Strong Breed. He took the loss as a tithe to the gods: a play about sacrifice being seized as sacrifice. But a year later, in the shock grip of perfect recollection, he typed it out again. Why did you gods take so long?

His choice of Ogun as avatar goes beyond the deity being the essence of creativity and therefore of literature; it begins from the deity being a kind of chosen one in Yoruba metaphysics, what he has called an “embodiment of the social, communal will.” The deity is “constantly at the service of society for its full self-realization” and “it is as a paradigm of this experience of dissolution and reintegration that the actor in the ritual of archetypes can be understood.”

It led me back to A Dance of the Forests, to the poet and woodcarver Demoke whom Ogun uses to sow strife through the murder of his apprentice. Was it intentional to position the artist, vessel of Ogun, as a potential saboteur of communal harmony, since artists generally keep their individual vision even at the expense of collective responsibility? It is a question with larger ramifications, that casts a shadow on the acrimony back home over his legacy.

“You know, I always contested the notion that the writer has a responsibility,” he began. “I don’t mean saying that the opposite is the truth, that the writer has no responsibility, no. I’m just insisting that the writer is also just a human being with all the virtues and flaws of people in other preoccupations, and that the responsibility of nation-building should not be placed on the writer alone. The writer has a vision of his or her own in addition to the vision of others, including the politician. At the same time, when I speak of Demoke as a flawed artist, it’s deliberate. Society is flawed. Models are flawed. History itself is flawed. And that’s why I utilize, as a cautionary instance, the historical flashback, of Mata Kharibu and the Court. And the writer is within that. But I use Demoke also as at least somebody who’s trying to create something positive. Something both symbolic and actual, derived from the past but suited to the present and indicative of the future. I place Demoke, the artist, in a very special position, but I do not romanticize that individual. That’s it. I did not want the writer overburdened.”

As we swanned through his divergence of social vision and ideology, I brought up his distinction of tragedy from comedy and our conversation hit an early hurdle. I had referenced another masterwork, The Lion and the Jewel, and an unrelated passage from Myth, Literature and the African World about Ben Jonson and Moliere; I was asking if comedy, unlike tragedy, cherry-picked material from the full range of human experience, if humour is found in that shrinking of totality — and Soyinka said, “Wait a minute.”

I stopped.

“See, we’re getting into very deep literary analysis here,” he said. “And I don’t like soundbites. A question like that requires a full exposition. We don’t have the time for that.”

I closed the book, misunderstanding. “I’m not looking for gotcha answers.”

“No, no, no. I’m just saying that an interview of this kind is just not the platform for deep literary analysis of relating in any satisfactory depth the nexus between, for instance, ideology and literature, ideology and wood carving, ideology and music, ideology and the plastic arts. These are very valid questions. What I’m saying is that this platform is just not suitable for going into that. To me, this is what I do in the classroom all the time.” He was smiling, pointing at my copy of his book. “I can see that it is well annotated. You’ve been reading of it in-depth. There’s no question at all about it. Questions like this require expositions which I just not —” He sought the right word.

“I understand.”

In the early 1970s, braving the drain of war and imprisonment, Soyinka overburdened himself with curatorial work. He was working on the anthology Poems of Black Africa when he began to edit Transition. The magazine, founded in 1961 by Rajat Neogy and based in Kampala, had risen as a meeting ground and common face for the decolonizing Anglo-, Franco-, and Lusophone intellectuals. Its voice was multifaceted and clear, and in 1968, it criticized the Ugandan president Milton Obote’s proposed constitutional reforms. Obote jailed Neogy for sedition and “subversive” ideas. When Neogy came out, he resumed publication from Accra, but funding had dried up.

“The prison experience sort of sapped him,” Soyinka recalled. “He was a very fragile person, even though he had enormous moral and intellectual courage. So it was a combination of lack of funds and the sort of — Rajat had become alienated, frankly, from the magazine internally. And so it was going to fall apart.”

The magazine moved to London, under a new name, Ch’indaba, Zulu for An Important Matter. And then tragedy hit. “There was this scandal that some CIA money had come into it. And, ironically, the steps we took to raise funds just catapulted Transition further down the bankruptcy line. The CIA was spreading money all over Latin America, Australia, Britain, France. Unbeknownst to Rajat, they had been laundering money into Transition; there’s no question at all about it. And we had to admit, frankly, that Transition was no tool of the CIA.”

When they put out a statement, the roof descended on their heads. Funders cut them off. Partnership offices in France closed their doors. The team couldn’t believe it. Transition was too good a magazine to go down, so they opened to adverts, anything to save it. In 1973, Neogy asked Soyinka to become editor, and Soyinka brought the publication to the University of Ife. With no funding, he got only three issues out of it before accepting that it was over. It was not until 1991 that the magazine would be revived at Harvard, by his former student at Cambridge, Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

“It was a strange experience to find people transition from being colleagues and friends to suddenly turning their back on you simply because you wrote the truth,” Soyinka told me. “The hostility. So it added to my conviction. They must have known. They must have been party to it. And that was the guilt and annoyance of being exposed. And we didn’t even attack them. We just said CIA money had been coming into Transition. Now we were looking for independent funds. Clean funds. And for that, we got clobbered.”

It is now widely known that many African literary and cultural initiatives of that period, including the Makerere Conference, were, without the knowledge of participating writers, clandestinely funded by the CIA through the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF), the Farfield Foundation, and the British magazine Encounter. The generosity was only an extension of Cold War battles to control the continent’s ideological persuasion — battles that ran deeper within the capitalist bloc, with the British Council, the Alliance Francaise, the Goethe-Institut, and Scandinavian bureaus in stealth competition. Still, out of it came a large African literary-cultural imprint on the Western mind.

I told Soyinka that the state of African literary funding is no better today, a path stricken with government meddling; for the right price, friends have, as happened with Transition, turned against friends. Yet funding is not the only problem that their generation of Black-owned media faced and ours still face. Weeks before our meeting, Essence magazine’s flagship event, the Essence Festival, took heat for, among other problems, catering to Africans and not its primary audience, Black Americans. The aspiration to global Blackness is thornier for a perceived paucity of resources and spaces. It is almost as if the efforts of his generation to reach across the ocean were not properly inherited, and, even faced with the peaking threat of White nationalism, Black unity was regressing.

“It isn’t that I’ve tried to unite Africans and the diaspora,” he replied. “No. I’ve merely acted from a — I can’t explain it, but it’s something rooted inside me that I’ve never accepted permanent separation. I’ve always believed that, just as with the Jews, the African continent is always there for Africans of the diaspora. If we must have some links outside, those links should benefit our own selves who just happen to be outside. Why should we restrict them?”

There was no reason to confine the concept of Africa to the continent. In the early ‘90s, he visited Jamaica twice and found Bekuta, named after his Abeokuta, a vanishing settlement with Yoruba ties. It was a time when he feared for his life, and he wanted to be buried on that island.

“The religion of Africa is in Brazil, is in Cuba, is in Puerto Rico, Colombia,” he noted. “You go there, you see, you live African cultures, spirituality, in some cases synchronized with the Christian religion, especially Roman Catholicism. It’s my sense that ‘Africa Overseas’ is less slightly different from ‘Pan Africanism,’ which is slightly political. But, for me, both the politics and cultures are totally enmeshed. That’s why, even till today, I’m canvassing for an irregular return. We call it the Heritage Voyage of Return. The idea is, a boat, every year, will leave the diaspora, go through the islands, stop at all possible ports where there was any kind of connection with the Slavery crime against African humanity. Africa should be recognized as a permanent home for Black peoples everywhere. Of course, only for those who need it.”