Years ago, while in university, the Ghanaian rapper Delasi travelled to the Volta region of the country, where he hails from, and began to ask his uncles about the origins of their family. He asked his aunties and his mother to translate their Ewe proverbs for him. Taken by the mythologies and folklores of his people, he noted everything he could.

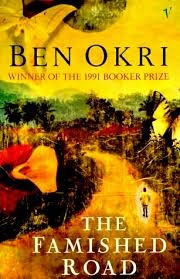

His sudden quest to rediscover himself and his roots came about because he read a book that his mentor and collaborator, Nii Nortey, gifted him: Ben Okri’s The Famished Road. It is the story of a spirit-child named Azaro who lives between the worlds of the living and the beyond. The enchanting cosmology of the novel awoke a hunger in Delasi. After visiting his family, he started incorporating his new cultural consciousness in his music, reaching a new peak with “Agbe Dzidzi,” the opening track on his EP The Audacity of Free Thought.

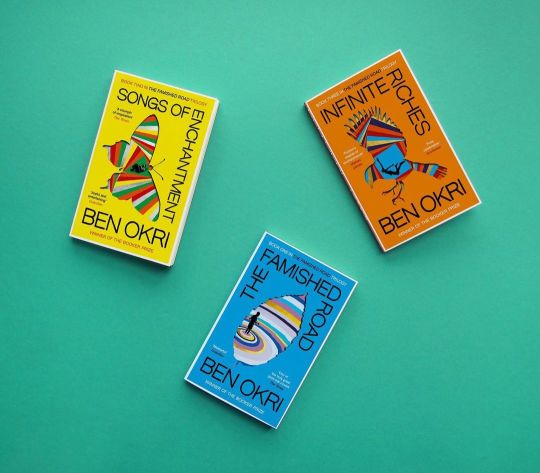

The Famished Road, which in 1991 made Okri the then youngest winner of the Booker Prize at age 31, is the first in a trilogy of novels exploring the African worldview through a consciousness that bridges the physical and spiritual worlds. The other books are 1993’s Songs of Enchantment and 1998’s Infinite Riches. Delasi read these, too.

“The Famished Road really made me dig much harder because it was just a fantastical magical incredible work of art,” he wrote in an email.

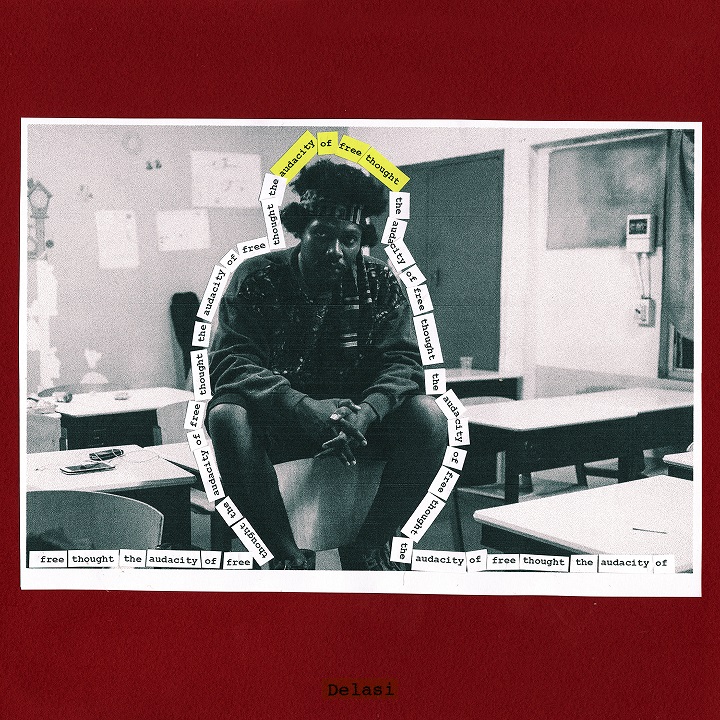

Ahead of the January 19 release of The Audacity of Free Thought, Delasi’s publicist Sope Soetan reached out to Ben Okri for a conversation: musician and novelist discussing the intersection of art forms. They asked Open Country Mag to host and publish it.

Over Zoom, Delasi, who is based in Ghana, and Okri, based in the UK, opened up, with me moderating it from Nigeria. What started as a few questions about conscious art acquired a life of its own and became a deep dive into spirituality, the kind that we are not accustomed to witnessing in public.

“The spirit dimension is a fifth dimension added unto reality,” Okri said at some point. “Actually, it is not really added unto reality, but it is a fifth dimension that is a part of reality.” This, he said, was part of what he set out to show the world in The Famished Road Trilogy. It is striking also to hear him narrate his creative process for the books.

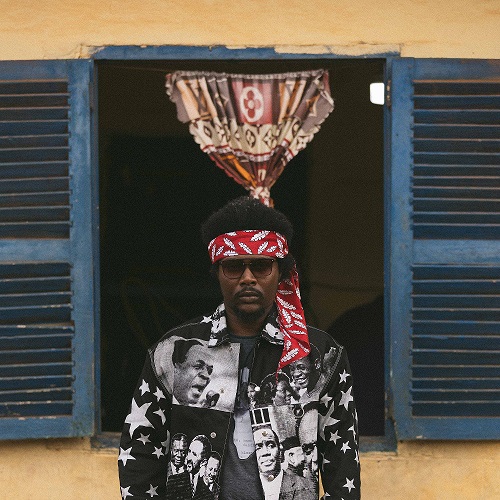

Delasi’s first project was Imperfections: The Break Up, Vol. 1, a 2013 collaboration with Yaw P. The Audacity of Free Thought, released by Brownswood Recordings, brings his journey of self-discovery, spirituality, and influences into his craft. The EP is, as he put it, “at various turns spiritual, aggressive, experimental and socially observant.” It is music that aims to challenge conventions. “I consider myself as an electronic griot of sorts,” he said.

Interviewer

I want to begin with the importance of conscious art in today’s society. Ben Okri’s works have been globally acclaimed for how they have shown to the world an African way of thinking, the African consciousness of seeing the world. The worlds of the living and the spirits are not seen as mutually exclusive but as co-existing, and that is what magical realism in the African context shows. It has been useful in espousing political, cultural, and even day-to-day life consciousness. Delasi, your new EP is a product of conscious art meeting a conscious artist. On the track “Agbe Dzidzi,” I hear that supplication to the spiritual which embodies that connection to both worlds. Tell us about how Okri’s own approach to conscious art helped you understand yourself and your identity better.

Delasi

Nii Noi Nortey, a multi-instrumentalist who was one of my collaborators for this particular project, gifted me The Famished Road and then Infinite Riches over a decade ago, when I was fresh out of university. Back in university, I had my heroes. One of them was Ghostface Killah, because of his prolific powers of narration in rap. There is a song by him called “Underwater,” where he’s talking about swimming and praying with mermaids. That was the soundtrack in my ears every morning and every night, to and from playwriting class. So now I come out of the university and I was on a quest, asking: Who am I? Where did I come from? But what really triggered this was The Famished Road. It blew me away. I was transported into another world.

So I began a quest. I travelled to my hometown, in the Volta region. Talked to two very knowledgeable uncles, bombarded them with questions about where we came from. They told me we were from a warrior tribe, they told me about the history, myths, legends, the proverbs, and taboos that protected our people and kept them living in harmony. We also discussed the efficacy of herbs, particularly some rainmaking herbs employed by the village in times of drought. I soaked myself into all these. The aftermath of it was that I was going to try to incorporate my mother tongue, the instruments, as well as texture and ambience of where I was from into my art, into the music. Okri’s work had so much impact on me because it made me want to rediscover who I was.

Ben Okri

It’s very interesting that you should say that, because the impulse behind The Famished Road was, in many ways, a similar impulse. Except it was an almost existential, cultural, and spiritual traditional quest that was thrust upon me as a writer and as a human being. I came to England with two novels, and they were written in the tradition of the English novel made famous by people like Jane Austen. A great tradition which we have soaked in, and is part of the African literary tradition, the beginning-middle-end way of expressing characters. There’s a kind of linearity to it.

By the time I came to the end of my second novel The Landscapes Within, I realized the kind of novel I was trying to write. The world I had grown in as a child, the African universe, my father’s way of looking at the world, my mother’s way of looking at the world, those deep elders, those things I grew up with. When as a child they took me to the village and put me through the most extraordinary ceremonies, and I soaked in stories, moonlights, and walked round the village, and had all kind of ancient traditions, and they were all right there sleeping inside me. And I just had this crisis, because I was writing this beginning-middle-end novel.

But the reality I had grown up in was not beginning, middle, end in the same way. It was much more tumultuous, coterminous, everything flowing into one another, reality was itself mythical, the myth was realism, the stories were myths, the myths were stories. Everything was mixed into everything else. And when I thought about it, this great European tradition, of course, cannot express this African richness, this African layered richness of spirituality, of tradition, of history, of proverbs of destiny. The novel we inherited cannot express this world.

So I went to look for the things that could convey the completeness of the spiritual world. It took me to music. I listened to music from all over Africa, all over the world. I was looking for something: music, art, architecture, sculpture, novels, poetry. So, in a sense, I was engaged in the same quest of identity you talked about, but my quest was to find a language with which to express the richness of the African consciousness.

I believe so much that when you express that consciousness, you liberate the African spirit. It took me almost ten years to look in. And so I had to create a new kind of language very slowly. The most important thing was to find a language that was open to all the mysteries, and to the realities, to the effect of the colonial presence, because that’s Africa, too, now — you can’t take that out of the picture. Africa’s all of that. Africa’s hugely absorbent, in its psychic embrace and spirit. The African spirit can absorb moon travel into its spiritual matrix; people forget that aspect of us: the elasticity, the size, the breadth, there’s no fixed shape to our spirit.

That’s what I was looking for. And so it makes sense that it was also able to engender a quest for identity. That’s what a novel like that really is about. It’s about the mystery of our origins, and ways in which those rich origins permeate, and inform all aspects of the comedies and tragedies, and joys and ordinariness and extraordinariness of our everyday lives.

Delasi

To add to your response, Ben, my forays and attempts to learn to write more in my mother tongue has opened other tongues more. My mother was my Ewe dictionary for a while. But now, I don’t know if I’ve gotten a bit better or just complacent, or found a Google Ewe translator. But the experiment in using my mother tongue for writing has opened a new layer of meanings, new proverbial ways of saying things. I’ll just make a simple lyric, and when I want to get the meaning of these things, it happens that it’s saying more than I want to say.

For example, on my debut project, #thoughtjourney, I wrote a song called “Lom Na Va.” My mother listened and she told me, “My son, what you have written is an oath of allegiance that the chiefs say when they are being sworn in where we are from.” Now, of course, I have never witnessed any chief being sworn in, but there’s a spiritual knowing that the African has, especially when you tap into the African identity and consciousness when you do all these works of investigation.

Even for this new record, “Agbe Dzidzi,” there’s a part which goes, Me ga tror megbe/ Me ga kpor megbe, which means, Don’t turn back, don’t look back. And the response for that is: Megbe, megbe, megbe. Which means, Back, back, back. And the double entendre for that is: I refuse, I refuse, I refuse. I just wanted to point that out.

Interviewer

Mr. Okri, your writing inspired Delasi’s music, and now you said that, on your own quest to write The Famished Road, one of the areas you looked at was music. You also looked at sculptures, you looked at poetry. Tell us more about that intersection, where music meets poetry and poetry meets storytelling and storytelling meets sculptures. Yes, all forms of arts meet to inspire each other, but how do they meet in the human consciousness?

Ben Okri

I think there’s been a profound misunderstanding about the place of these diverse arts as you speak of them within our tradition. I say this because, between our traditional matrix, we don’t really make a separation within all of these forms. You know, when I was growing up, when the elders told stories, they told stories with music. Once upon a time, there was a tortoise. . . and then they broke into song. And if they had an instrument there, they’d play it for a bit, and then they’d go into the story again, and then they’d tell some of it, and then they’d go into music, and some poetry, and it was all mixed in. It was all a part of their way of expression.

We’ve now compartmentalized storytelling, poetry, music, sculpture, but I believe if you track it down to the source of the African spirit, you’ll see they come from the same place. When people are making sculptures, or portraits, they are incantating at the same time, they are chanting, singing songs as well, and sometimes people are telling stories behind them. All of these forms, they all feed on each other.

It’s only because we’ve come into these postcolonial times, the effect of the Western mind on us, has led us to this idea of separation. Actually, if you looked at the Western tradition, in ancient Greece, poetry and storytelling and music were mixed and intermingled. I think, in most traditional cultures, these things were intermingled, because how can you tell a story without music, or how can you make music without telling a story? How can you make a bronze image or a stone image without incantation, without poetry? How can you do it without the spirit of music? All of these things are interpenetrative, and that’s what I was trying to say.

The Famished Road Trilogy is an interpenetrative world of all the arts. If you look at the books, they are making things, they are telling stories, music is part of it, singing is part of it, and it’s all part of expressing the deep matrix of our spirit. So I think we need to lose this idea of separation. When I heard Delasi’s music, I heard stories, I heard poems, I heard the abstract beats of those African afternoons, and you know the music comes from the reality, and the reality affects the music. It’s not just that the art forms affect one another. It’s also that our environment, our atmosphere, the land itself has a beat or encourages the creation of a beat. This, too, affects the art.

Delasi

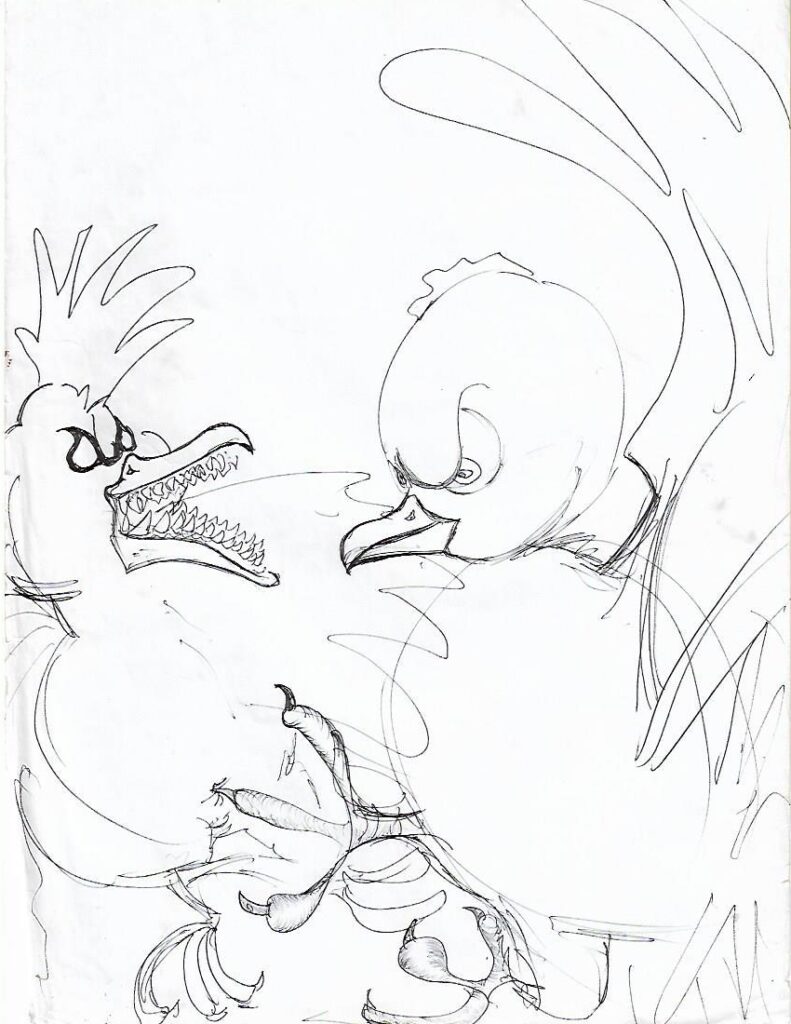

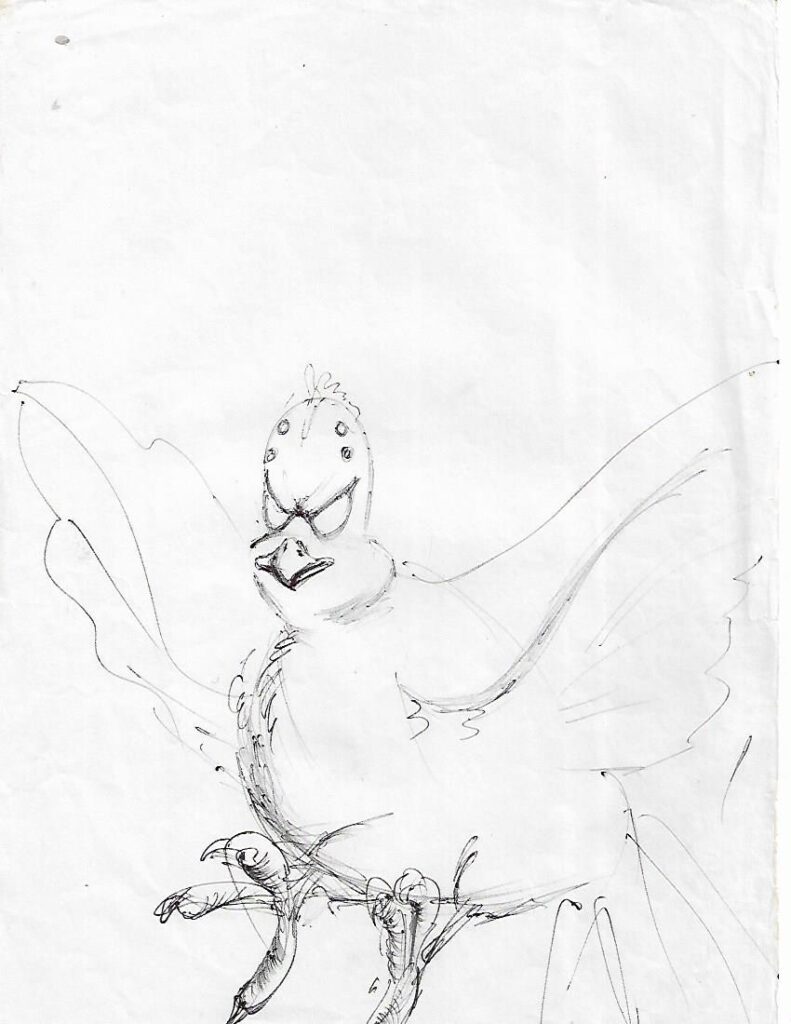

[Delasi brings out some of his drawings and shows them to us].

This was me before The Famished Road. And this was me after.

Ben Okri

Your hand expanded.

Delasi

Yeah, but not just that. My thinking, my perception, and my awareness. In my playwriting class, the lecturer would say, “If you are not paying attention, you miss out on a story.” This is how I was aware or conscious of my surroundings to be able to write a story: sit in the bus, hear people’s conversations, and, before you know it, I am writing a story about their whole lives, and I don’t know them, or anything about them. I just observed them. I just tapped in.

Art is very encompassing, like Ben was saying, where you break into songs in the middle of a story, to sing about a protagonist or an antagonist; we have that tradition. Even when in a song, you are praising a king or maybe you are talking about the ills of society, you know. This is culture. Songs can accompany what may be considered as non-creative activities such as fishing, farming, or some manual labor; this helps boost morale to complete these tasks. I consider myself as an electronic griot of sorts. It’s not oral tradition of the purest form, but this is my own way of paying homage by letting all this research, nature, and everything around me influence my work.

Ben Okri

Can I quickly add something? Something I have not really expressed so far. And that’s the spirit dimension. You know, in the West, they take the spirit dimension to mean something supernatural. As if it was just these weird figures in the margins of the narratives. What has happened is that they have been soaked into the Christian tradition, which has shut their minds. What they don’t understand, (my readers in the west, and some of my readers in Africa as well), is that the spirit dimension is not a material dimension, it is not ghosts, or something like that. The spirit dimension is a fifth dimension added unto reality. Actually, it is not really added unto reality, but it is a fifth dimension that is a part of reality.

We don’t see it because we’ve become trained to not see that dimension. And so what’s happened to us over the years is that we have shrunken our sense of reality. In order to function in a new reality that has been shaped in our minds, and encrusted in our culture. But the fifth dimension of the African mind, of the African world, is a dimension all of its own which changes everything.

It is not just an expansion, and that’s exactly as Delasi was saying. It’s not just that he’s painting differently. It’s that he sees differently. He’s seeing what’s there, and what is not there that is there.

Delasi

And the in-between.

Ben Okri

And the in-between. It really is about liberating our perception so that we can see the universe as richly as our ancestors did. That’s what made them so resilient, that’s what made them so chilled about the universe in which they lived, it’s what made them strong, it’s what made them telepathic, it’s what made them mysteriously powerful.

I could tell you a lot of stories about my grandfather, my great-grandfather and great-grandmother, and things which they did which will have your hairs standing. The things these people could do now that is lost, now that we think we are so clever because we have gone to university and read books of astrophysics, physics, and the Greeks Classics, and we know more, but we actually know less. But this is a whole new conversation that should be a symposium for us.

Listening to Delasi’s EP, but “Agbe Dzidzi” in particular, I think he tapped into that extra dimension and found something quite special. I played it to some of my friends, and they found a lot of unusual energy in it. I think you found something and I think you should continue with that inspiration.

The thing about the richness of the African consciousness and why I keep going on about it — it’s not that I’m trying to oppose it to the Western consciousness, I’m not trying to say, well, they have their way of doing things and we have ours, and if you understand ours you can’t understand us. No, that’s not why I’m doing this. I’m doing this because the African consciousness, when we go back to its original splendor, gives us access to many more dimensions of being and possibilities. I think all of creativity comes from the true source of your psychic consciousness. I think we need a return, or maybe a going forward, to the African consciousness, which is what Delasi’s experimentation is all about.

You’re doing it with all of your music and exploration because you are a child of your tradition as well as your time. Delasi, is that so?

Delasi

Very much so. And I want to say on record: I do not consider The Famished Road Trilogy as just books of fiction. I have a song titled “Naija Movies be Real.” I met a real-life Madame Koto, who was determined to take me out. While I was battling the witchcraft spells, and all of that, something else was happening: a fifth dimension opened, or maybe a fourth, it opened where you could see spirits, malevolent and benevolent. You could feel them and it heightened my intuition. Of course, that would affect some of the art I was making, it was a great battle while I was fighting for my life, but at the same time, this was an extension of a fever high or lucid dream that I would have had as a child. This was an extended form of a lucid dream, and it bares gifts.

Ben Okri

Yes, yes, the gifts are ambiguous; yes, I know what you’re talking about. In order to finish the first book of The Famished Road Trilogy, I went through battles like that, too, every day, every night. For a whole month I could not sleep because all the doors of the mind and the spirit were open. My girlfriend at the time was scared for me, she thought I was going to go crazy. And I learnt something my father told me, that there’s no way you can go through this life without redoubling the strength and walls of your psychic spirit. I needed the strength of the psychic and spiritual world to even begin to write those books every day, every night. So my advice to anybody who wants to take this journey: while you’re doing it, strengthen your psychic walls and psychic spirit, strengthen your core. This world, its gifts are mighty, but they are ambiguous gifts.

Interviewer

Delasi, what do you say to that? Ben just spoke about the importance of strengthening one’s psychic powers to go through this journey, and you told us earlier about your heightened consciousness as a result of your experiences. What effects have these heightened powers had on your music?

DeLaSi

I was telling my friend, Sope, who is a wonderful publicist, that one of these gifts, the ones I can actually perceive, really scares me, and this is the gift of foreboding. Dreaming things and then it comes to pass in too much exact detail. Or I just innocently write a song and it manifests in too much detail, and I become scared of myself (laughs) and what I wrote because, I don’t know if I’m a conduit of sorts channeling something from a certain frequency. It’s a scenario that scares me so much that my resolve is to only write kind and meaningful things. I can’t write violently, even if it’s not about my story, you know, if it’s something I’m observing — it scares me too much because I just noticed that’s one thing I can see now, I just dream something and then it’s too clear and too exact. That part of me scares me, that’s one thing I can share.

Ben Okri

Well, it’s all part of strengthening your psychic walls; when you get into this work, you become open to the future. And it’s very simple because you know time is unreal. You know they’ve taught us wrong at school. They give us the distinct impression that the past, present, and future are distinct phases of time. It’s not true. Time is not real. I know this for a fact. The future is as much here as the present, and the past is not ended yet.

When we say we dream the future, it’s not that we go into a future time, we just go into the present but in a very profound way, we are all timeless here; but most people don’t access this because they live in demarcated time perceptions. But this work, this spirit work, transcends time. Not only do you have these forebodings you talk about, but you also have projections, which is to say the things you think, sometimes they happen, too. So we have to be very responsible, apart from strengthening our psychic walls.

We can’t mess around with evil, and the work you have to do has to be for good and for the good of humanity. If you don’t have anything to say that’s good, just be quiet until you have something that’s either going to strengthen us, or help us see well, help us see far, help us see where we need to go, help us become the people we need to become in order to change the destiny of our people, of our continent.

It’s big work. This work is bigger than the works of heads of state — I used to say that when I was writing the trilogy. Heads of states pass laws, they change things, and things get worse or better. But that is official. But this work we do is spiritual, it is the work of how people see themselves, the work of how people perceive their possibilities, it’s very deep work that goes on and on into the future, generations and generations.

It’s the work of the true artist, not an artist in the Western perception but in the African perception, the old African perception. Which is, you are dealing with the soul of your people, you are dealing with their destiny, their fate and futures and where they are going to be and what they are going to become. We give them vision, we sow seeds into their dreams. So we have to be strong, we have to be good people in a sense. Not boring good, but good in the sense of having a good destination where we are thinking and dreaming of our people. We have to be creatures of light, not darkness.

We are supported by all the great ancestors. They support us when we are at work. I’ve had visions of old, old storytellers, storytellers that I didn’t know where they came from. Long dead, still living. They’ve come to me in my dreams when I was writing the trilogy. It’s big work, Delasi.

The only question I want to ask you: how did you choose your instruments, for these new songs? What are these instruments?

Delasi

On my mother’s side, they are musical educators. I have cousins on that side who can play anything. Unfortunately, they don’t show off as much as I do. Maybe they show off just in the church. The economy messes them up, so they are bankers, and maybe they can play like Jimi Hendrix, but the guitar is in the bedroom, nobody hears it, while me — I took that bold risk. You know, my Dad was a lawyer —

Ben Okri

Like mine, like mine.

Delasi

(Gives a nod and thumbs up).

— I get my visual aesthetics from him but I got the sonic aesthetics from him too. He introduced me to his myriad collection of vinyl records. So I was drenched in music from the jump.

The first instrument that I remember playing was the piano, and that’s courtesy of my dad, too, because he took me to a piano class in a conservatoire to learn. But as an adult now, I’ve been finding myself flirting with different instruments. I’ve owned the mbira, I’ve owned a keyboard, I’ve owned a guitar, and studied playing traditional Ghanaian drums as well. None of it really made sense until I became a producer where I could become an electronic conductor, so I can just program these things and then on this record.

Ben Okri

The electronic is very sensitive to the spiritual world.

Delasi

I’m not playing everything on this record, but I play a lot, and I had assistance from some friends, mostly in New York and New Jersey. Nii Noi Nortey, the master jazz musician who introduced you to me as I mentioned in the beginning, plays the saxophone on one of the records.

Ben Okri

There are many sounds, many worlds of sounds and hymns and suggestions, and hymns and suggestions, half hymns, and half worlds, half mystics going on there, and I found that fascinating.

Delasi

Thank you, Ben. Tell us more about your relationship between the electronic and spiritual worlds.

Ben Okri

In many ancient cultures, electricity was a hint of the vibratory nature of other dimensions. So working with electronics in music lends itself to capturing and hinting at the fuzz and unreality or even the super-reality of the spirit world.

Delasi

Isn’t it very interesting that we are both artists today, but children of lawyers? I think it’s important to lay some emphasis on the importance of the nurturing support of African parents, where it is very rare for them to back their children who venture into the arts (because, traditionally, they would rather you take on corporate interests instead) and how it can affect their art. How can young African artists go against the grain, be audacious enough to express their free thoughts?

Ben Okri

African parents tend to be conservative in their aspirations for their children. They want their children to pursue solid and dependable professions. This is understandable. Perhaps the best thing that African parents pass on to their children that stands them in good stead whichever path they chose is that, whatever one does, one must match and even surpass the professionals. A good work ethic, a passion for craft — these are good African values that help children to find their own true way.

It is up to us practicing artists to persuade them by our success and our contentment that the way of art is one of the greatest ways to serve our people and make a decent living. It is a fruitful and invaluable way of life. But it must be a calling and we must bring to it the highest standards.

I got this from my father. He wanted me to be a lawyer, but instilled in me the solid qualities without which one would fail as a writer or artist. With the way the world is going, we are going to need the arts more than ever. For me, creativity is the means through which we will meet challenges to come and harvest the possibilities that have always been there.

Interviewer

Delasi, your EP is titled The Audacity of Free Thought and aims to carve its own path, separate from that set by gatekeepers in the music industry. How does your EP represent the task of its title?

Delasi

The musical space, at least speaking from where I live in Ghana, is rigid and geared towards a very specific genre. The tastemakers, the playlisters, the media who propagate this sound in Africa and to the world do not give alternate narratives or textures of sound a chance to thrive. My work is a bold statement of defiance, to break away from what is being pushed down the public’s throats as the only representation of what defines African music. I believe that African stories surpass the stereotype of an overly exaggerated simplistic reveler glorifying the nightlife or abusing words through lyrics about a love interest. There are far more stories that need to be told. ♦

Edited, and with contribution, by Otosirieze.

If you enjoyed what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

No One Covers African Literature, Nollywood, & Industries Like Open Country Mag

— Alhaji Waziri Oshomah, a Muslim Highlife Pioneer & ’70s Star, Returns for Legacy

— The Next Generation of African Literature Is on the Cover of Open Country Mag

— The Fates and Faith of Tunde Onakoya

— How Leila Aboulela Reclaimed the Heroines of Sudan

— Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is in a Different Place Now

— The Epic, Transformative Comeback of Chidi Mokeme

— Rita Dominic‘s Visions of Character

— Nonzo Bassey‘s Songs of Heartbreak

— Maaza Mengiste‘s Chronicles of Ethiopia

— Chude Jideonwo on His SARS Victims Documentary Awaiting Trial

— From Dreams of Music, Football, & TV, Bada Akintunde-Johnson Sets His Style

3 Responses

Such a great interview . Love Delano

Absolutely amazing interview between the 3 of you. Wow….thank you. Blessings!

Amazing