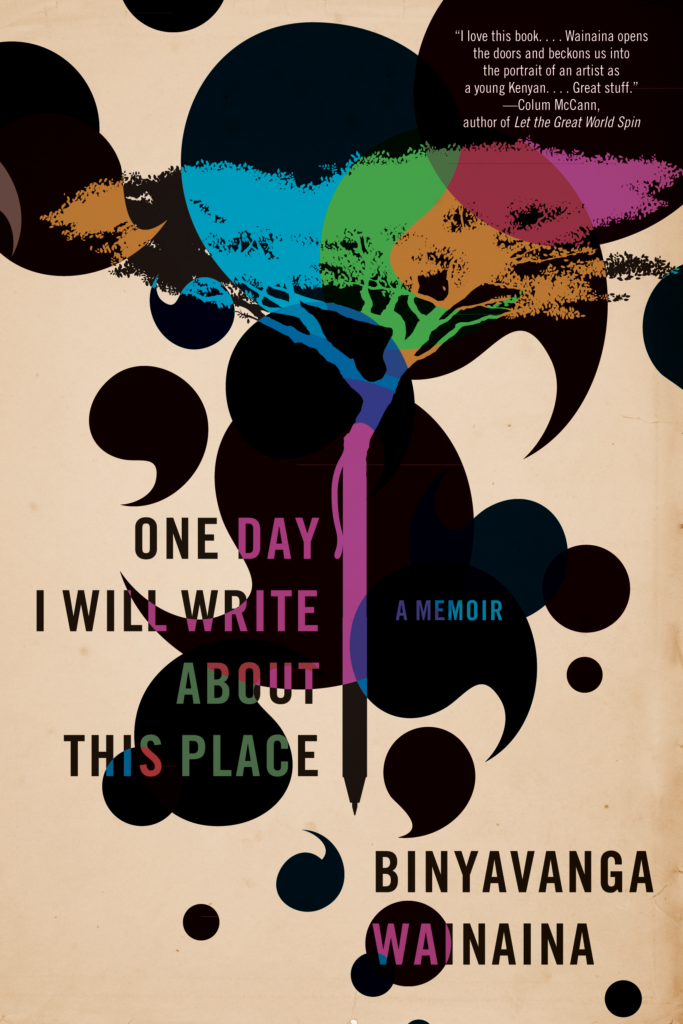

The Kenyan writer, journalist, and activist Binyavanga Wainaina passed on at age 48, on May 21, 2019. He died in Aga Khan Hospital in Nairobi, after a stroke, an illness he has had since 2015. Wainaina, who won the Caine Prize for African Writing in 2002 for the short story “Discovering Home,” authored one book, the memoir One Day I Will Write About This Place, published in 2011.

Born in 1971, in Nakuru, a bonny city in northwestern Nairobi, he was the founding editor of Kwani?, a defining literary outlet in the 2000s. He wrote several short stories, but more widely read are his essays, cheeky, sweet, and moving. “How to Write About Africa,” a piece of sharp, ironic beauty, published in Granta 92, in 2005, is one of the most read pieces on the magazine’s website.

Two years after his death, Binyavanga Wainaina is still remembered for his energy, his unabashed honesty, his poignant words.

Here, an assortment of quotes—pulled from tweets, essays, his memoir—about, among a sweet variety of other things, words, love, purpose, literary politics, identity, and rage.

1.

“I am seven years old, and I still do not know why everybody seems to know what they are doing and why they are doing it.”

— from One Day I Will Write About This Place.

2.

“[I write] because I have been reading a book a day since I was six … was addicted to fiction, and I believe fiction is better than the real world.”

— from an interview with Pambazuka.

3.

“We’re in the age of this kind of neo-liberalism. Some people use it to acquire certain freedoms—women in particular, for example. But it brings all kinds of threats. You have societies like Kenya where your traditional systems are completely destroyed. So they have no real force and power. And so the idea of a person as an individual in the world is stronger in Nairobi and other parts of Kenya than it is in different parts of Africa. It’s also pretty strong in Cote d’Ivoire, which I realised when I went there. But part of the problem is that there are all kinds of fragilities embedded in that idea too.”

— from an interview with This Is Africa.

4.

“Within the space called Nairobi—within the urban spaces—you have a generation of people who have a lot more self-confidence about who they are. And whether or not whatever they are is pure, in those very Africanist terms people like to throw back at us, they are very confident about expressing who they are. That is a significant shift from the seventies and eighties, where it was more about who do you need to be, who do you want to be?”

— from an interview with Tin House.

5.

“There is always that point at a party when people are too drunk to be having fun; when strange smelly people are asleep on your bed; when the good booze runs out and there is only Sedgwick’s Brown Sherry and a carton of sweet white wine; when you realize that all your flat-mates have gone and all this is your responsibility; when the DJ is slumped over the stereo and some strange person is playing ‘I’m a Barbie girl, in a Barbie Wo-o-orld’ over and over again.”

— from “Discovering Home.”

6.

“Hey mum. I was putting my head on her shoulder, that last afternoon before she died. She was lying on her hospital bed. Kenyatta. Intensive Care. Critical Care. There. I am holding my dying mother’s hand. I am lifting her hand. Her hand will be swollen with diabetes. Her organs are failing. Hey mum. Ooooh. My mind sighs. My heart! I am whispering in her ear. She is awake, listening, soft calm loving, with my head right inside in her breathspace. She is so big – my mother, in this world, near the next world, each breath slow, but steady, as it should be. Inhale. She can carry everything. I will whisper, louder, in my minds-breath. To hers. She will listen, even if she doesn’t hear. Can she?”

— from “I Am a Homosexual, Mum.”

7.

“That it is not day. It is night. That your eyes are sticky. That you are sick. You know that kiss, your mother’s fever kiss? It comes to you every year. She sings softly and spits her chew into your mouth, herbs and hot mush, pastes of beans, blood and milk, in small bits. Then your mum croons and goes out to stick her beak in the belly of a motorcycle trapped in a fashion shoot. Even now you can smell burning meat. Your fingers dream-bling!”

— from “A Short Biography of Wangechi Mutu.”

8.

“I am starting to scribble my thoughts, to write these moments. It is only when this is all done that I do what I do best. I look up, confused and fearful…then soak in the safe patterns of other people, and live my life borrowing from them; then retreat—for reasons I don’t know—to look down, inside the safety of novels; and then I lift my eyes again to people, and make them my own sort of confused pattern.”

— from One Day I Will Write About This Place.

9.

“There will be this feeling again. Stronger, firmer now. Aged maybe seven. Once with another slow easy golfer at Nakuru Golf Club, and I am shaking because he shook my hand. Then I am crying alone in the toilet because the repeat of this feeling has made me suddenly ripped apart and lonely. The feeling is not sexual. It is certain. It is overwhelming. It wants to make a home.”

— from “I Am a Homosexual, Mum.”

10.

“Kenyatta is the father of our nation. I wonder whether Kenya was named after Kenyatta or Kenyatta after Kenya. Television people say Keenya. We say Ken-ya. Kenya is 15 years old. It is even older than Jimmy. Kenya is not Uganda.”

— from One Day I Write About This Place.

11.

“Nairobi is a strange and interesting place. Unlike Lagos or Kampala, it really doesn’t belong to anybody. That’s the worst and best thing about it. People may have very strong opinions about things, but they also inherently hate the idea of you saying, ‘This is African culture or this is whatever culture.’ They say, ‘No, no, no, me I just want to be anonymous in the city. I don’t need you imposing this weird thing. I do my thing.’”

— from an interview with This Is Africa.

12.

“I knelt down and asked my love for his hand in marriage two weeks ago. He said YES. We will be married in South Africa early next year. I am beside myself with excitement that he has agreed to spend the rest of his life with me.”

— from a tweet, May 2, 2018.

13.

“I assume that most, like me, are tempted to go anyway because we will get to be ‘validated’ and glow with the kind of self-congratulation that can only be bestowed by very globally visible and significant people, and we are also tempted to go and talk to spectacularly bright and accomplished people—our ‘peers’. We will achieve Global Institutional Credibility for our work, as we have been anointed by an institution that many countries and presidents bow down to.

The problem here is that I am a writer. And although, like many, I go to sleep at night fantasizing about fame, fortune and credibility, the thing that is most valuable in my trade is to try, all the time, to keep myself loose, independent and creative… it would be an act of great fraudulence for me to accept the trite idea that I am going to significantly impact world affairs.”

— his response to being nominated by World Economic Forum as one of 250 Young Global Leaders for 2007, a nomination he declined.

14.

“It is a season of mad beautiful ideas, not safe career bum lickings.”

— from a tweet, October 10, 2014.