On a cold evening in January of 2011, some of Nigeria’s most celebrated figures gathered in Victoria Island for an event they considered a major stop on the culture calendar: the sixth edition of The Future Awards Africa. Their influence and affluence drew both the country’s traditional media and its growing social media to Landmark Events Centre. Inside the lit hall, on the stage, stood Genevieve Nnaji, the most elusive of them all. She was the continent’s biggest actor, standing next to its biggest blogger, Bella Naija founder Uche Pedro, both standing next to a physicist and mathematician, Debo Olaosebikan, who was part of a team developing the world’s first electrically operated silicon laser. Alongside them were the singer and rapper Nneka, whose tune “Viva Africa” was on the official soundtrack for the 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa, and the intrapreneur Ojoma Ochai, the Assistant Country Director for the British Council and a UNESCO global expert panelist. They were nominees for the final award of the night: Young Person of the Year.

Also up for that category, but not in attendance, were P-Square, the continent’s biggest music act; Blessing Okagbare, the Olympics silver medalist; Don Jazzy, the music producer whose label Mo’Hits had taken over the airwaves and streets; and Makinde Adeagbo, a software engineer with Facebook whose work — reducing over 1 MB of JavaScript to 2 KB — made the app load twice as fast.

None of the nominees were 31 yet. Standing at the forefront of entertainment, technology, and policy, they embodied, even for their audience of successful guests, a version of the Nigerian Dream. But that night, the award did not go to a celebrity. It went to a problem solver. Nnaemeka Ikegwuonu, a broadcaster with over 250,000 daily listeners, had used his reach to educate farmers and foster agricultural solutions.

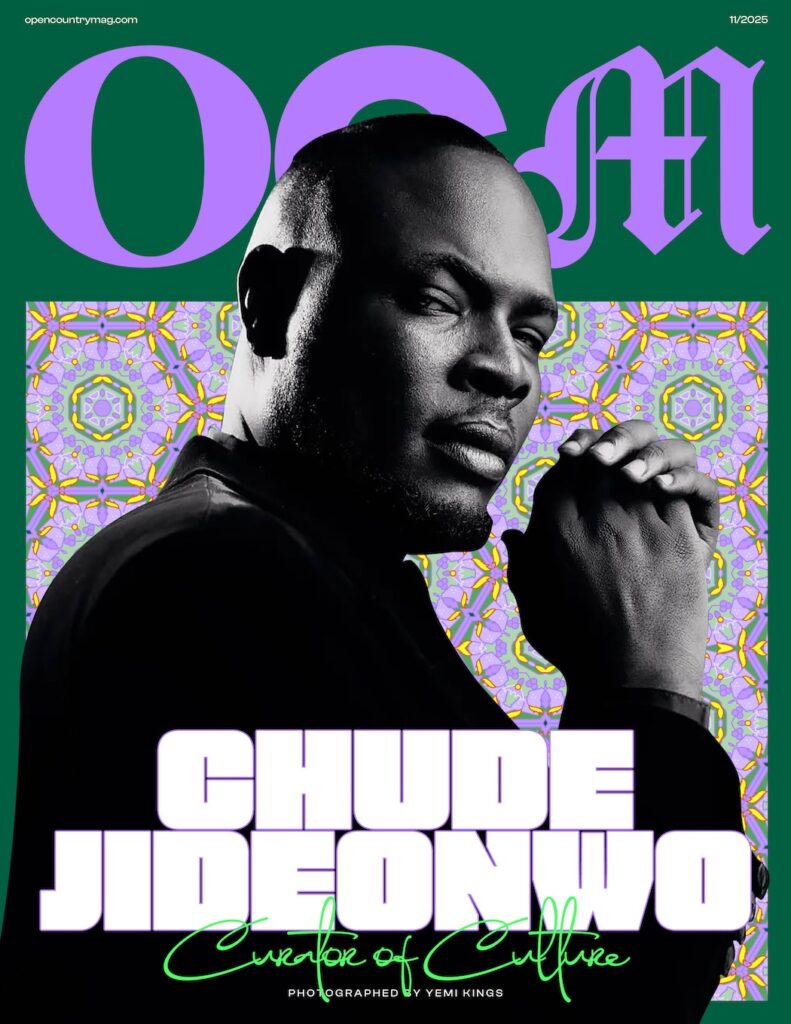

“It just captured our vision,” Chude Jideonwo told me. He’d co-founded The Future Awards Africa to celebrate young people between the ages of 18 and 31 for an accomplishment in the previous 12 months. He was doing it by bringing together the younger and older generations under one roof. It was meant to be a generational page-marker, the anchor of a youth-driven era, the most important stage in culture. “An actor, a music producer, on stage at the same time for Young Person of the Year. Typically you wouldn’t see that. And it is that merging of professions that makes it unique. The Future Awards is still the only prize that I know that does that kind of merging.”

Chude had always liked stars. “There is something about the human capacity to just shine that validates the human spirit,” he told me on a Zoom interview in June. The mid-2000s, when Chude himself came of age, made stars of young Nigerians. Oluchi Onweagba, who won The Face of Africa in 1996 at age 16, had become a model of international repute. Agbani Darego had won Miss World in 2001. Ndidi Nwuneli had founded the youth leadership program LEAP Africa. Afrobeats was rising, and TuFace Idibia, P-Square, D’banj, and Styl-Plus were superstars. Nollywood was growing, and Genevieve Nnaji and Omotola Jalade-Ekeinde were its faces. Sefi Atta had published her novel Everything Good Will Come. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie would later win the Orange Prize for Half of a Yellow Sun. The country’s biggest international exports were the footballers Kanu Nwankwo, Jay-Jay Okocha, and rising star Mikel Obi.

“Between 2003 and 2006 was a brilliant time to be young in Nigeria, such a glorious time,” Chude said. “People take it for granted now. We couldn’t take it for granted when I was growing up. I remember thinking to myself, ‘Oh, my God, I want to celebrate these people.’”

He discussed the vision with his business partner, Adebola Williams, and a third partner, Emilia Asim Ita. They’d started a communications company called RED | For Africa in 2006. Now they wanted to use it to acknowledge the young stars’ accomplishments, for the stars’ stories to be in the mainstream. “I remember us saying to ourselves: let there not be a time in the future that we’d be saying, ‘Oh, young people used to do incredible things,’ just like we now say, ‘Oh, there was a time when Coke was one naira.’ We didn’t want to look in the future and say that time has passed. We also wanted to change the negative narratives about young people being scammers and ‘no-gooders.’ If a young person in secondary school saw a strong positive image, they could say, ‘I can become this person.’ So we thought: it’s not enough for Oluchi to just be it. Why did she become it? How can we ensure that young people on the streets hear about it, are inspired by it, take action?”

The three partners decided that an award would achieve that. It would draw everything to itself; it would attract media attention.

But nobody understood what they were trying to do. Prospective sponsors kept asking why they couldn’t make The Future Awards Africa a youth movie or music event. “And we were, like, how can you not see the beauty of this? No, we wanted a melting pot where a musician and a banker can share a stage. And even now, thinking about it, I’m, like, ‘My God, I’m so proud of myself as a young person,’ because it would have been infinitely easier to have just done what they said.”

They ran out of money even before the day of the first edition, in February of 2006. They went to Maryland and Ojuelegba to post flyers on bridges because they couldn’t afford to hire people to do that, and they would wait until midnight to avoid being harassed while doing so. On the date, the event started late because they had to sweep the hall themselves; they couldn’t hire cleaners.

“The financial difficulty was incredible,” Chude recalled. “And I did feel a little resentment, because I thought this work we were doing is important and it’s popular. I shouldn’t be begging people to support it, you know? The Future Awards is important to the culture, whether the culture knows that or not.”

Although there was support from people in media, there was no sponsorship for the first four years. “I mean, we got maybe like N500,000, but it was usually individuals who believed in it.” He worked at Storm Music then, setting PR for the label’s artistes including Ikechukwu, Darey Art Alade, and Sasha. The label head Obi Asika would reach out to people on their behalf. Some of their prospective sponsors wanted some control in the organization. They didn’t grant it. It wasn’t until that sixth edition, in 2011, that they managed to secure brand sponsorships.

By 2013, The Future Awards Africa had become the centerpiece of the culture calendar, attracting an invitation from President Goodluck Jonathan. The ceremony for that ninth edition, on December 20, 2013, was held in Aso Rock, in Banquet Hall, the most important hall in the Presidential Villa. On the most symbolic physical stage in the country, being broadcast live on NTA, Chude delivered his opening address to the political, industrial, and cultural elite. He was still only 27.

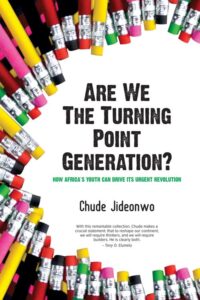

The Aso Rock event presaged an upward career storm, transforming Chude Jideonwo from a culture curator to a larger generational symbol. In February of 2014, Farafina published his youth leadership manifesto Are We the Turning Point Generation? In April, he gave his first TEDx Talk in Akure. In May, he was invited to the World Economic Forum (WEF) on Africa, held in Abuja, as a Global Shaper. In August, Guinness made him a brand ambassador for its Africa-wide “Made of Black” campaign. And in October, CNBC Africa honoured him and his RED | For Africa co-founder Adebola Williams as Young Business Leader of the Year, West Africa.

The Future Awards Africa was not the only pacesetter that Chude built to sell culture. RED | For Africa had a subsidiary called Generation Y!, housing media content targeted at millennials, from the TV shows Rubbin’ Minds and eXplorin! to the online publication YNaija. When YNaija launched in May of 2010, people wanted it simplified for them. “Are you a newspaper? Is it a fashion magazine?” they asked. “No, it is a culture magazine,” Chude would say. The problem, again, was not definition; it was assimilation. “We came out and launched ourselves as the high priest of the culture. But what the fuck is this ‘culture’?”

YNaija, with its signature annual lists of influential figures in different spheres, quickly became a major Nigerian publication. It also fostered a wave of culture writers. Many of them were young, new, and sought out by Chude from newspapers and blogs. Some — Wilfred Okiche, Eromo Egbejule, Kathleen Ndongmo — are now notable journalists, but they each had their first bylines on YNaija or were paid for the first time for their writing by YNaija. The credibility and launching pad it provided would inspire platforms to come. It was another advancement for the culture, only that, this time, even he could not have predicted it.

Chude’s editorial instincts gave YNaija its voice, and when he stepped down as CEO of RED | For Africa in 2018, the platform struggled. “That’s why magazines like Vanity Fair and Vogue will have the same editor for decades, because, unlike with an organisation like BuzzFeed, culture platforms often rely on a particular point of view.” Subsequent YNaija editors, “who were passionate, who were informed,” tried to channel his voice. “That’s why media businesses are often not scalable businesses and don’t get venture investments, because the venture capitalist is thinking to themself, ‘If this voice goes, what happens to the property?’ That’s why we at YNaija began to look at BuzzFeed, for models that could be replicated regardless of who the editor was. Venture capitalists make all these estimations, and we only learned that later.”

YNaija and The Future Awards Africa were remarkable results in a system resistant to ideas from young people. On our video call, Chude had turned off his camera and his tone took a dip. “Nigeria is a tough place to do nuanced things, like Open Country Mag has also discovered.” He recalled telling a Nigerian editor at an international outlet that he wanted to write about culture, only for the editor to ask him what culture was. “He’s, like, ‘What is culture?’ He wanted a simple box. He wanted me to say music or movies. I’m, like, ‘No, culture is the integration of how we live our lives. And that’s the exact intersection that I want to write about.’ Nigeria is not the best place to do complex things. People like simple things. People don’t understand what culture is. All I’ve always wanted to do is to interpret culture, to accelerate culture: this moment is happening — how do you make people understand it?”

Chude first understood culture through his father’s library of mostly African books. They were books most people his age would find inaccessible: Ayi Kwei Armah’s The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu’s Because I Am Involved, and Wole Soyinka’s The Interpreters, among them. There were newspapers, too, and talk show hosts on TV. Reading made him aware that people were doing important things, that people could impact the world with words, printed or broadcast. It fueled his ambition as an only child. In his family’s small apartment in Ijeshatedo, Lagos, in that compound of nine families, reading made him conscious of his place in the world.

His family also provided an awareness of the political shape of things. His father, a civil servant, was a politically conscious graduate of the University of Ibadan. He was the first person from whom Chude heard about joining a protest as a citizen. By age 12, Chude had listened to all his parents’ debates: whether the family should vote for Bashir Tofa or MKO Abiola; whether June 12 was an impasse; whether Oladipo Diya was an accomplice. He knew that the unending names that came up — MD Yusuf, Kudirat Abiola, Tunji Braithwaite — belonged to people affecting the state of the country.

In primary school, imagination ablaze, he wrote a novel and a classmate illustrated the cover. He wrote another. But when, at 13, he wrote his third, he wanted more: publication. “I wasn’t writing it out of some fantasy or ‘Oh, I wanted the world to see it, I wanted people to know that I could write,’” Chude said. “At that point, I’m just, like, ‘Look, I want to do important things in this life. I can’t just be writing books. I want to be published.’ I was incredibly ambitious as a child, like the kind of ambition that could possibly be parodied.”

He posted letters to some of his favourite columnists, seeking advice on how to publish a novel. Two working at Vanguard replied: Helen Ovbiagele, the paper’s Woman Editor, and Angela Nwosu, a fiction writer and arts columnist. Nwosu told him that publishing was difficult; he shouldn’t get hung up on becoming “the youngest author in the country,” which was his goal; he should instead focus on writing the best book and becoming the best writer he could be. On her recommendation, he looked at the back pages of all the books he could find and posted letters to countless publishers. He was a student at Mayflower School, Ikenne, Ogun State, then. An editor at Goldfield Publisher came to his school for the manuscript and published it.

That childly ambition was nudged by his mother’s belief in him. She, a pastor, told him how prophets stopped her on the road to say that her child would be a great man, that his name would be known, that she alone must raise this child; and they said these without asking for money. Even when her marriage got difficult, she insisted on not leaving him, Lagos, or her marriage. In her chase of a second child, she had ectopic pregnancies, almost losing her life.

Difficult doors opened easily for young Chude. He attended a deliverance programme at Mountain of Fire and Miracles, Yaba, where he saw the legendary TV host Dr. Levi Ajuonuma. His mother told him to introduce himself. He did. A few weeks after, Ajuonuma introduced Chude and his novel to his audience, and, right in the middle of the show, made him host of the show’s youth segment. It was his first TV host gig.

He was 15, a year younger than the university age, when he gained admission to study Law at the University of Lagos. His mother refused to have her son swear a false affidavit that he was a year older. She took him to the vice chancellor’s office and, after daily follow-ups, he approved her son’s admission.

“I think my mother is the single most important person and factor in my life on any level,” Chude told me. “She did the emotional labor of raising me. She was an incredible role model in terms of just finding your way in the world.”

By 17, he had a rooted sense of expansive possibility and was already a producer at New Dawn with Funmi Iyanda, which was on NTA. By 18, he’d met his business partner, Adebola Williams, and they’d started RED | For Africa. By 20, he was entertainment editor at Hot magazine and was writing for Hints magazine and Big Brother Naija. It was also then that RED | For Africa launched The Future Awards Africa, a peak stage for curating culture that, only five years later, led Chude into the thrilling highs and deep lows of politics.

The rupture of the relationship between Chude Jideonwo and the Goodluck Jonathan administration, a major champion of RED | For Africa’s youth-centric work, has been a subject of speculation. Yet that perceived relationship was never smooth. Before Chude, in 2011, became, at 26, the youngest person to interview a sitting Nigerian president in Jonathan, Chude helped lead a protest against the Umaru Musa Yar’Adua administration in which Jonathan was Vice President. In March 2010, barely a month after President Jonathan became Acting President in the absence of the reportedly ill Yar’Adua, Chude sent an enraged email to his network of influential young people, including activists and celebrities. He titled the email: Where is the courage?

“Our president has been missing for about three months,” he said. “Women in Jos had done a naked protest because the deaths, the killings, in Jos had reached an alarming rate, and our president was missing, and I just thought, ‘We must be an insane country.’ How can a president be missing? A whole president of a country?” There was fuel scarcity, too. He asked his friends, “Is this how we’re going to be sitting here, drinking wine, and talking? Are we not going to do anything?”

He approached Save Nigeria Group (SNG), a coalition of human rights and pro-democracy activists founded by Tunde Bakare, which was gearing up for another protest. Chude told SNG that, with him and his friends running the biggest youth platform in the country, their voice would add renewed energy to the protest. But an SNG representative, he said, suggested that they be in charge of entertainment. “I thought: ‘This guy is not taking us seriously.’” The coalition worked out eventually and became the 2010 #EnoughIsEnough protests, which was held in major cities and, later, morphed into a youth advocacy group.

That May, with Yar’Adua finally announced dead, the Senate confirmed Jonathan as President. A well-meaning man, younger and not authoritarian like his predecessors and eventual successors, he was the country’s first leader from a minority ethnic group: the Ogbia, who are often misrepresented as Ijaw. In a country that prioritized ethnic affiliation over competence, his heritage, and the fact of a Christian Southerner succeeding a Muslim Northerner, was the stumbling block in his confirmation.

Jonathan was the first and only president to invest in the entertainment and culture industries. A dream romance bloomed, and Aso Rock became a hotspot for actors, musicians, and the curators bringing them together. RED | For Africa was also establishing itself in the broader political scene. The then Lagos State governor Babatunde Raji Fashola hosted some winners of The Future Awards. The then Ekiti State governor Kayode Fayemi hosted The Future Awards Symposium for Young and Emerging Leaders. The then Rivers State governor Rotimi Amaechi hosted two ceremonies for The Future Awards.

Even as rifts began in the ruling People’s Democratic Party (PDP), shifting political alignments in the country, RED | For Africa navigated it. In 2013, it received invitations from both President Jonathan and Governor Amaechi, who had defected to the rival mega coalition, the All People’s Congress (APC). The company reaped twice with two editions of The Future Awards ceremony: one in Aso Rock and the other in Port Harcourt. “That made me proud because it showed that the Awards was non-partisan,” Chude said.

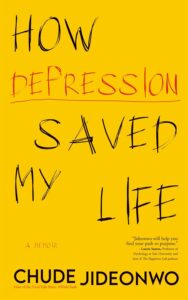

Things soured after April 2014, when the terrorist group Boko Haram invaded a school in the northeastern village of Chibok and abducted 276 girls. Jonathan’s critics claimed his government was warned of the attack in advance, and had enough time to save the children, but had calculated it as a ploy by the APC opposition. The government denied this. Chude describes this moment in his memoir How Depression Saved My Life. At first, he thought the defence made sense: the opposition was vehement in its critique of the government and the president was levelheaded, a quality he Chude had experienced firsthand.

But in May, at the World Economic Forum in Abuja, in that gathering of world political and economic leaders, the abduction was the discussion. Chude writes that a Senior Special Adviser to the government pulled him and two other people into the corridor and claimed that the president was lying; he had indeed delayed intervention because he was convinced the situation was a plot by the opposition. It was that information, Chude said, that changed his stance.

This was only weeks before his book launch and tour with Are We the Turning Point Generation? He knew he would be asked about the Chibok girls onstage, on camera. Whatever he said in response would decide the fate of the fame and network he had worked hard to acquire in the previous eight years; it would decide the future of RED. In How Depression Saved My Life, he writes:

It wasn’t in my interest to speak against a government that had, just months before, been extremely gracious to us. Yet I had no choice but to say what I honestly thought, on every stage I was on, to every camera that faced me, from CNN to Aljazeera: the government had failed.

I didn’t just speak; I went on the streets and protested. I burned bridges.

The consequences were swift and as expected: businesses and government officials distanced themselves from us, we lost contracts and sponsorships, and we lost face. Consulting was our core business. The government was our biggest client. I was attacking a government I was seen as being close to, a perception that brought with it immense power, and I was very visible in doing so. To transparently attack the government in a country where government is the biggest spender is already unwise if you run a business. But to do it when you wield heightened influence because you are close to the government? That was career suicide. So for months, our business faced its first real crisis – and it was all my fault.

The APC chose Muhammadu Buhari, the country’s military dictator from 1983 to 1985, as its candidate for the 2015 elections. Governor Amaechi, the director-general of the campaign, invited Chude and his business partner Adebola Williams and made them an offer. “Look,” he told them. “I think you guys are smart. I’ve seen what you’ve done. I know that in private conversation you’ve said that you are very angry with this government. Well, here’s the opportunity to take down the government you say you are angry with. Do you guys do this kind of work?” They said yes and joined the Buhari campaign as its communications front, with their political strategy arm StateCraft.

Buhari won the 2015 elections, securing 15 million votes to Jonathan’s 12 million. It was the first time, in the new democracy, that a sitting government had been defeated. In another first, Jonathan congratulated Buhari.

But Chude’s hope that Nigeria was on the right track lasted two months. “We expected him, naive, silly children as we were, to hit the ground running. Ex-governors had prepared policy papers, drawn up cabinet suggestions. We thought, ‘Look, in these three months, like, after the hoots, let’s start moving.’”

President-elect Buhari did start moving — for needless courtesy visits in lieu of starting work. Then one of Chude’s friends who worked with the campaign called him and said, “Man, Chude, we’ve made a mistake. This man listens to nobody. This man obviously just used everybody to win this election. I think we’ve made a mistake.”

Chude writes in his memoir that, at once, he felt it in his soul that he had been duped. But since Buhari had not yet been sworn in, he refrained from what he thought would be hasty judgement. He would give Buhari three months, he told himself, and if, after three months, he still saw the same inertia, then he would speak his mind. He would question if this man even understood how high the stakes were that brought him into office.

But there was no change after three months, and Buhari’s eight-year presidency proved to be a stunning disaster. His incompetence decimated Africa’s largest economy, pushing it into two recessions, in 2016 and in 2020. His ethnic aggression reopened old wounds, specifically against Igbo people in the country’s southeast, and heated the atmosphere of a country that once approached unity under Jonathan. Insecurity rose: Boko Haram remained active in the Northeast; banditry in the Northwest; deadly Fulani herdsmen attacks and kidnappings in the Northcentral; and in the Southeast, the secessionist agitation of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), which started as a nonviolent movement, was repressed and snowballed into a violent conflict. The military was massacring thousands of citizens, most notably members of the Islamic Movement of Nigeria (IMN) in Zaria and members of the IPOB in Aba and in Onitsha. On October 20, 2020, it opened fire on peaceful EndSARS protesters in Lekki, Lagos; Amnesty International estimates that up to 103 people were killed. Civil liberties were further eroded. And, under his rule, young Nigerians began a mass exodus that the brain-drained country found a term for: japa.

The optics reflected harshly on Chude. He had criticized the Buhari administration and declined to do more work with it. But as he cut ties in private, StateCraft was extending its powerful PR to other African presidential elections. In 2016, it led the successful campaign of Nana Akufo-Addo in Ghana. In 2017, it strategized the reelection of Macky Sall in Senegal. In 2018, it joined former Sierra Leonean Vice President Sam Sumana’s bid for the top job. The same year, it advised the Kenyan opposition leader Ralia Odinga on coalition-building efforts. But back home, its reputation was darkened and, for Nigerians who sought accountability and placed blames on social media, Chude became the intellectual target of that anger.

One morning in 2017, Chude woke up to see his name trending on Twitter (now X). The subject was a piece he wrote for Quartz, exploring why African youths kept voting older men into office. The piece was commissioned to offer an outsider perspective on the election of Donald Trump in the United States, but it was read as a defense, two years into the disaster, of his choice to work for the Buhari campaign.

The backlash was sharp, deep, and continuous, a reflection of the country’s rage. For Chude, who had been a public figure since his early 20s and was used to criticisms, this one felt personal. He panicked. He felt what he called a “righteous anger.” So he defended himself: he had acted on a deeply held political conviction in 2015, which was his right as a citizen. His defense only enticed more backlash. Tweets recalled his claim that he received spiritual clarity to support Buhari and accused him of using Nigerians’ gullibility about religion against them.

Some could not understand why he could not simply apologize for his role in bringing Buhari to power. He had hosted national events, led protests, published books and essays on leadership. They had not trusted many other prominent Nigerians who supported Buhari over Jonathan, but they trusted Chude because he was young and therefore should know better. And if they could not reach those other Nigerians now, they would direct their ire to Chude. He was supposed to be one of them. Why did he betray them? How could he not have known better? Why would he not apologize? What made him so arrogant to imagine that politics was like culture and that he could change the former the way he’d changed the latter?

Chude explained the problem to me: he would not apologize because he would not be dishonest with himself; he had worked for Buhari out of a conviction, not ignorance. But something had also broken in him, and in 2018, he stepped down as CEO of RED | For Africa.

Although he stopped taking on political assignments, Chude did not stop engaging political culture as a storyteller. When he launched his film studio, Chude Jideonwo Presents, his first project, in 2022, was a documentary on the families of police unit SARS victims. He called it Awaiting Trial, to denote the larger prison system in which to be “awaiting trial” was to be forgotten and consigned to subhuman cell conditions. The documentary proved popular.

But the decision of the studio to release Is It Your Money?, a four-part documentary on Diezani Alison-Madueke, Jonathan’s Minister of Petroleum who was being trailed by heavy charges of corruption and embezzlement, woke up the ghosts of an era that would have benefitted him to move on from. It had been 10 years since Jonathan left office; corruption and the general standard of living had worsened under Buhari and Tinubu; why would a documentary on political corruption ignore the horrible present and not focus on any of the many Buhari and Tinubu associates under whom the country currently bleeds? While many viewers welcomed its revelation of the depths of corruption, Is It Your Money? was largely received as an effort at distraction and ignited a new wave of criticism.

Chude let out a drawn-out sigh. “It is as funny as somebody asking me, ‘But James Nwafor’s [the corrupt, murderous SARS official documented in Awaiting Trial] offense happened under Jonathan. Why are you talking about SARS under Buhari?’ I think the arguments are just easily defeatable. They’re not even coherent. Awaiting Trial criticized the Buhari government. But, of course, these are not good-faith questions; they are a political battle; they’re political dance questions. Somebody says, ‘But your very first documentary focused on Buhari, why didn’t you focus on Jonathan?’ So that’s one way to dismiss it. Like, I’ve done documentaries about Buhari’s actions. I’ve written articles against Buhari; they are in the public. I have undeleted tweets criticizing Buhari while he was president. Do you understand?” Chude laughed; sarcasm. “The laughter in this answer should be communicated in the article because it’s not even a serious argument — it’s just easily defeatable.”

He paused, sucked air, snorted. “When you attempt to tell a great story, you look for a great subject. And all the partners, all the funders I have pitched ideas to, know that I have pitched about several governments. It’s just the one they chose to fund that they funded, you know? Is It Your Money? was funded by the MacArthur Foundation. They don’t have an agenda. They’re not part of Nigerian politics. They wanted me to do a documentary that explains how corruption works. The person who even pitched the idea, Nodash Adejuyigbe, one of Nigeria’s top filmmakers, is not even a political character. Before then, I wasn’t thinking of a documentary on Diezani, but Nodash just said, ‘Look, who is the most colorful character? Who is the character that has all the elements of a great story across several countries? Who is the character that has rich complexity and detail?’ And we story-boarded it, and we arrived at Diezani. There was no political consideration. None at all.”

Most of the interviews in Is It Your Money? were shot in 2022. “So, I’m supposed to have projected myself to the future, knowing that Tinubu was going to be president, delayed my shoots in order to instead make a documentary on Tinubu?” There was irritation in his voice.

Another hangover from Chude’s political past: Jonathan’s attempted fuel subsidy removal in 2012 and the resultant Occupy Nigeria protests, facilitated by the EnoughIsEnough group. Eleven years after Jonathan reinstalled the subsidy, Buhari removed it in 2023, ushering in more debilitating economic consequences than those imagined in 2012. People have asked why EnoughIsEnough and Chude have not protested against it.

“That often misunderstands the nature of public protests,” Chude replied. “Nobody owns the protest, typically. Occupy Nigeria was a protest made up of different, aligned groups. Many of the people in that protest, I haven’t seen since the protest. Many were strange bed fellows bound by a common cause, you know? So those that say that often do not in good faith.”

He paused again, sighed. “Who is the Occupy Nigeria that should come and protest? That only happened because there was an Occupy movement across the world. That Occupy movement has exhausted itself. But even more to the point, a lot of the parties who were part of that protest have been organizing public action. [Omoyele] Sowore was part of it; he has been organizing public actions. EnoughIsEnough Nigeria was part of it; it has been organizing public actions. So it’s, like, really, is that question being asked in good faith? Or is that part of the performance of blame that we do in Nigerian political culture? If you are angry about fuel subsidy, the person to hold responsible is the person in charge of the policy, whether it’s the president or minister; it’s not the person who protested against the policy years ago. We should stop chasing shadows.”

Nigerian political culture misunderstands the nature of both movements and public anger, he said. “It assumes that all of us are calcified in particular opinions. That’s a fallacy. It assumes that the person that believed that fuel subsidy should be removed in 2012 still believes that now. Nigerian political conversation bores me, because it’s static, it’s frozen in time but never on a policy level. In America, some conversations are frozen in time because people are Marxists or communists or capitalists. But in Nigeria, it’s just a freezing of perspective, a freezing of thoughts. There are many people I know who believed that fuel subsidy should be removed then, but who have subsequently been convinced, because they’ve gone on to run businesses; some of them have written articles about it. Principled evolution is based on exposure to superior arguments over time. There are economic experts who changed from being socialist to capitalist, who moved from protected economic advocates to free market advocates. And many of them don’t have any position in government, so it’s not as if there was [an ulterior motive]. So the nature of Nigerian political conversation is strange; it’s very strange, it’s very strange. That’s why I left it.”

I asked Chude if he was in that category, if his view on subsidy removal had changed, and he told me that he had not made a political opinion public since 2020. “And it’s not because I’m afraid. I’ve shared opinions when I had more to lose, [so it’s] not now that I am protected by hurdles of privilege [that I would be afraid]. My issue is, the work I’ve chosen to do now, in a country that easily misunderstands political intention, I do not want useless misunderstanding that doesn’t advance my goals, that distract me from the work I’m doing. That’s generally my response. But on fuel subsidy, specifically, I am observing.”

His ongoing observation is based on a policy evaluation of the elections right after the one he shaped: the 2019 elections. “All the candidates, their political and economic theories are often diametrically opposed. One of them is a clear populist, and there’s nothing wrong with populism. He believes in ideas of productivity and cost savings and pro-poor policies. Another one is essentially a socialist. He believes in a combined agenda of market-centered ideas that promote business and open the economy to foreign investment in a way that inspires global confidence in our markets, but he also believes in balancing that with pro-poor policies. Another of the major candidates was a pure capitalist, believing extremely in open markets, and his party espoused the idea. Now, all three market philosophies supported the removal of the fuel subsidy. All three. So because of that, there came a divergence of perspectives. The first subsidy removal didn’t have the consequences it was painted to have. So now I am observing: ‘Ah, okay, so what did they get wrong? What could have been done differently?’ So that’s where I am. I’ve always resisted [commenting on economic policies], because I’m not knowledgeable about the specifics of short-term market behavior, economic or monetary policy behavior.”

When I asked Chude to name which candidates he attributed each policy to, his team replied that “he prefers to leave descriptions the way they are.”

That morning in 2017 when Chude saw his name trending on Twitter, trailed by demands for accountability and outright verbal attacks; that morning, after he felt that anger to defend himself, something else happened that put his life on a different path. He fell into depression. Why did they hate him so much? He broke down in tears. His friends and associates thought it a non-issue that would soon blow over. But Chude did not want intellectual responses; he needed emotional succour.

On YouTube, he searched: What to do when people hate you? One result was an Oprah Winfrey clip from her Super Soul Sunday series. Winfrey is interviewing the motivational speaker Brene Brown. Brown is telling how she dealt with vicious online comments on her viral TEDx Talk. A Theodore Roosevelt quote, Brown said, changed her life:

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, who errs . . . if he fails, at least he fails while daring greatly.

Chude narrates this period in How Depression Saved My Life. He wrote that the quote comforted him. Things made sense to him again. An interview filmed in Chicago had changed the life of a young man in Lagos. He told himself: he would do a show like this one day. A show that someone could encounter in a clip and be touched, comforted, changed forever.

Around the same time, he discovered another work by two spiritual masters: The Book of Joy: Lasting Happiness in a Changing World by Archbishop Desmond Tutu and His Holiness Tenzin Gyatso, the Dalai Lama. “Who are you not to be criticized?” they ask in one chapter. The question, he writes, gave him perspective and quietened his sensitivity to criticism. People had been and would be criticized for things more consequential. What he felt was only the discomfort of being disliked.

Happy and bright as he was in the spotlight, he was low in spirits when alone. He took a break from RED. He took a position at Pan Atlantic University, Lagos, teaching media and communications. He planned to get a PhD in communication studies in the United Kingdom. Then things changed for worse at RED. The business stagnated. All their dollar-paying clients who’d signed contracts simultaneously refused to start work. Nothing he knew about business — strategy, commitment, consistency, hard work, systems thinking — was working. The company was almost broke and, for three consecutive months, they dipped into their savings. He panicked. He lost his sense of security. Now his critics would laugh at him. They would say: Chude entered politics and got no political appointment and now he was broke — even though he did not want an appointment. Questions mounted: Were his critics right? Were the curses on social media coming to pass? Was God punishing them in some way?

He writes that his faith in God was shaken. He started reading books about atheism and, later, agnosticism. He could hold opposing views in his head and was therefore also reading the Bible. That, he holds, led him back to God. He experienced “glimpses” of God.

It also opened a new door: joy. He found meaning. He felt an “exultation of my own spirit” in prayer, in worship, while reading a book, walking in the sun, inhaling in nature. He knew there were more depths to plumb. He altered his planned PhD to focus on the life of Christ and bookmarked three schools in the United States: the Harvard Divinity School, the Union Theological Seminary, and the Yale Divinity School. Then he heard about Yale World Fellowship; a RED board member, Biola Alabi, had just been selected. Chude applied and was selected. It was in America, during the fellowship, that he met Richard Sheridan, the author of Joy, Inc.: How We Built a Workplace People Love — a book he loved. Months later, he realized what he should do next: share the message of “joy.” The wealth of knowledge on joy is buried in books and the academia, and he wanted to free it to a mass audience. He dropped his PhD plans. He emailed Sheridan, for permission to use the name of his book, and Sheridan said yes. In December 2017, he set up a company named Joy, Inc.

At first, he contemplated staying back in America or going to the UK, but there were enough people popularizing “joy” in those places. Meanwhile, only a scatter of people publicly taught about mental and emotional health in Nigeria, much less joy, resilience, and flourishing. He would spread his message in his country, where it was urgently needed. He came back to Nigeria.

After Chude filmed the first 13 interviews of the podcast that became #WithChude, he did not release them because he did not see where they fit in a drifting online and media culture. He had left social media. He “followed his spirit” and launched several motivational projects: a newsletter called The Daily Vulnerable; a program called The Joy Masterclass, held in Cameroon, London, and New York, along with a summit titled The Joy Congress; another event about navigating work pressure called Stop Hustling; his #ChudesBookClub; and a Bible group called The Jesus Club, for those whose understanding of Jesus Christ is constrained by religion itself. Partnering with Olamma Cares, he launched a mental and emotional health walk-in centre in Lagos and called it The Joy Hub. Yet what “came from the purest place” were those 13 interviews. His guests ranged from singers and actors to entrepreneurs and activists, and they had discussed not entertainment but taboo and semi-taboo topics. Would a culture fixated on Internet skits and gossip not shun soft conversations on vulnerability and shame and mental health?

Especially when TV shows did not fare well in Nigeria. He recalled notes from his pre-fame career producing, representing, and hosting some that did fare well, including The Sunday Show with Levi Ajuonuma, Health Matters with Lilian Agbaso, Video Ten with Comfort Okoronkwo, Inside Out with Agatha Amata, New Dawn with Funmi Iyanda, and Moments with Mo with Mo Abudu. He considered RED’s own stable of productions, including eXploring, The Big Story, 21 Diaries, Church Culture, and the still-running Rubbin’ Minds, hosted by his friend Ebuka Obi-Uchendu. He didn’t want those interviews to come out and not do numbers, not make impact; they were too sacred to be released and be ignored, and so he held on to them for two years.

It was May of 2019 when a close friend, Mfon Ekpo, told him that Busola Dakolo, a photographer and wife of the singer Timi Dakolo, had a story that would interest him. The Dakolos had seen Chude’s work with Joy, Inc. and were convinced he was their safest bet to tell it. Busola Dakolo said that Biodun Fatoyinbo, the celebrity pastor of Commonwealth of Zion Assembly (COZA), raped her in her teens. In a country where religious leaders were untouchable, the accusation was shocking.

At first, Chude preferred for a woman to interview Bukola Dakolo, the story being a woman’s. But after searching in vain for a journalist who wanted the job, he took Mfon Ekpo’s advice to do it himself. He prayed about it, and they did the interview in a church. He published it on YouTube, using the hashtag #WithChude as a placeholder.

The interview broke the Nigerian Internet. International publications, from The New York Times to The Guardian UK, caught the scoop, and a Nigerian #MeToo moment arrived. There was vitriol launched at Bukola Dakolo and at Chude: people demanded that she “prove it.” Bukola Dakolo wanted civil justice, the matter reached the court, the police got involved, relationships broke. Above all, viewers had witnessed a public healing.

Although he worried that the public would think he was taking advantage of the Dakolo story, and that his interview style was not good enough, Chude took the advice of associates and released the other interviews. They launched through TVC Entertainment in April 2020, under the original placeholder name #WithChude, now official.

The show aired over 60 episodes in its first year. There was more positive feedback from people who said it touched their lives. Yet the show had not yet reached “a critical mass or made money.” One of its two advertisers dropped. In a private dinner in a Lagos restaurant, Chude tabled his concerns to friends: What could be done to reach more people? His friends suggested two things: the promo must be tighter; the conversations must pack a punch. A third model came during an interview with the activist and filmmaker Pamela Adie, who shared that, in order to recoup some of the investment from a film she co-produced, she put it on a paid website. She knew she might not make much from it, but wanted people to place value on her work nonetheless. Chude did the same.

The resulting website was a precedent for WithChude.com, a niche subscription video-on-demand (SVOD) platform he launched in 2024, housing the show as well as a pool of docuseries, factual films, and specials. Inspired by the Oprah Winfrey Network (OWN), he wanted it to be the first of its kind in Africa.

In a country whose biggest exports are brainpower and entertainment, #WithChude’s roster of high-profile guests and the guests’ willingness to be vulnerable have made the show a new centre of gravity in culture. The emotional resonance is so much that people stop Chude on the streets to say thank-you. The team says that viewers are paying, too, more than the show made from advertisers, and that the subscriber list has grown. Part of the success is also technical: a steady improvement in set design, camera work, styling, makeup, and sound.

The interviews happen in a sitting-room with green plants. The wallpaper, mural-styled and with a white background, is a spread of images: Lagos’s Aro Meta statues; colourful, graffiti-styled emojis; monochromic, line-drawn shapes. Chude and his guest sit on chairs, not slouch on cushion. The setup frames the uncommon thing it has become: a serious conversation between serious people about serious emotions. It is presented as a confessional space, and Chude plays Oprah. His listens with bespectacled eyes, his hand propping up his cheek, or a couple of fingers above his lips, nodding at the right times, arms folding and unfolding.

Many of the guests come in a fog of fame; the public sees them without knowing who they are, without understanding that they, too, carry human pain. But at the end of the hours, there is a demystification, and a new relatability emerges. The tears of famous people reliably go viral, and while such public confessions are enough to drive some away, the attendant boost in relevance and social media mentions makes many more famous people want to come on. Some go on the show to merely “trend.” Others go to softly rebrand themselves, and who better to ask them guiding questions than someone who has successfully rebranded himself a few times?

Naturally, any stage where people are given room to frame their own stories will attract politicians. Former president Olusegun Obasanjo — one of two men to have led Nigeria both as a military head of state and as a civilian, the other being Buhari — came on the show and defended some of his most controversial political decisions. He had publicly claimed that he had nothing to do with his administration seeking a third term for him in 2007. When Chude asked why he didn’t discourage those who were – his allies Tony Anenih and Ahmadu Ali, allegedly, among them – Obasanjo replied, “Did Anenih tell you that?”

Chude answered in the negative. “But you could have stopped him, sir.”

“But he didn’t tell me [he was] doing it. He did not.”

The former president pinned it on the governors: the governors wanted a third term for the president because it allowed they themselves to seek third terms.

Obasanjo was not the only politician versed in writing books and retelling his legacy to have come on the show. Nasir El-Rufai, the former governor of Kaduna State trailed by accusations of maladministration, claimed that he did not give “a damn” about the Nigerian Bar Association dis-inviting him to its 2020 virtual conference, despite a statement from his then Special Adviser on Media and Communication claiming the dis-invitation was unjust. El-Rufai, a central figure in major controversies that rocked the literary and journalism scenes, implied he didn’t sanction the response.

In late April, Chude sat onstage at The Palms Mall, Oniru, Lagos, before an audience of 5,000. The sold-out event, titled WithChudeLive, was billed as “the first-ever live talk concert out of Africa.” It was an exclusive roster of the single top achievers in their industry: the writer and culture icon Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, the preacher and highest-earning Nigerian YouTuber Jerry Eze, Nollywood’s highest-grossing actress Funke Akindele. One after the other, they appeared onstage, sharing snippets of their life stories. “I’m not one of those people who will come and start crying on your show,” Adichie joked.

When he curates an event, when he sits for an interview, he is looking for the dream in his guest’s story. He wants guests who trod rocky terrains in search of their own dreams. Some of their stories of reinvention mirror his. The data analyst Stephen Akintayo — who worked for both President Jonathan and his then rival Buhari during the 2015 elections — came on the show last year because he was in the same place as Chude: he had done business with the government, and when it failed, he stopped taking political gigs and began criticizing it. The wealthy Akintayo, who lives in Banana Island, told his story of hawking electronics and popcorn on the streets as a child, not seeing a water closet until he was 13, and of sending out 100 CVs and cover letters that asked for a simple job and no salary for six months — and still not getting a job.

“Sorry, sorry, sorry, sorry, sorry,” Chude brought down his crossed leg, punctuating the air with his hands, eyes flaring. “You gave a cover letter that said, ‘Just give me the job. Don’t pay me salary for six months.’ And you still didn’t get the job?”

“In this country,” Akintayo said. “I understand, really, what an average person is going through. And that’s why I was very much vocal, and I think I remain so.”

Chude listened to Akintayo narrate his start in data marketing through an SMS business, going to a cybercafé because he didn’t have a laptop, spending 14 hours from Sango Ota to Ikeja Along to paste posters that read: Buy bulk SMS, 75 kobo.

“So, you know, it wasn’t that, ‘Oh, you saw an innovation opportunity’?” Chude asked.

“No, no,” Akintayo replied.

“It was, like, poverty, and this was the only option?” Chude asked.

“It was the only option, no job opportunity, and this was the easiest business around. I mean, the entry barrier was very low.”

Later, Akintayo said to Chude, “Thank God I didn’t cry. They said people cry on your show.” The two burst into long, crackling laughter.

That moment of relief is something Chude hopes for. If he could have a life of receiving and creating opportunities and get here, if Akintayo could start with so little and still get here, then perhaps the Nigerian dream was not lost. Perhaps the Nigeria he imagined, the Nigeria that escaped his grasp, is still out there, in the dreams of others. ♦

Edited by Otosirieze.

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

More Cover Stories from Open Country Mag

— The Creed of Cardinal Arinze

— How Leila Aboulela Reclaimed the Heroines of Sudan

— How Rita Dominic Became Nollywood’s Most Acclaimed Actor

— Chinelo Okparanta, Gentle Defier

— The Next Generation of African Literature

— The Methods of Damon Galgut

— Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is in a Different Place Now

— How Teju Cole Opened a New Path in African Literature

— Maaza Mengiste‘s Chronicles of Ethiopia

— How Tsitsi Dangarembga, with Her Trilogy of Zimbabwe, Overcame