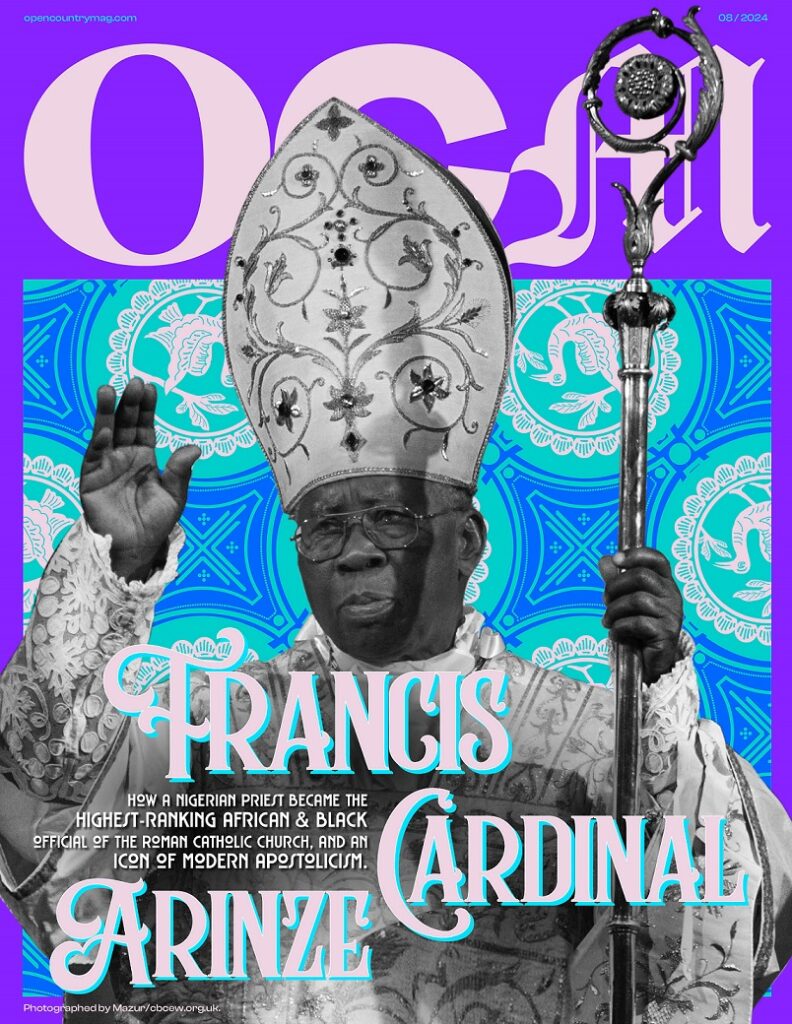

I.

“He would be in joy and in prayer”

Shafts of the evening sun once beamed into the Sistine Chapel from its twelve arched windows, sliding off stained glass to pour on the high walls and barrel vault ceiling, where, 500 years ago, the famed frescoes were cast. At first, the grand assemblage of Biblical and Messianic prophecy imagery was not meant to be that numerous. A trio of Italian masters of the High Renaissance — Sandro Botticelli, Bernardo Rosselli, and Pietro Perugino — had decorated the walls with stories of Moses and the Hebrew patriarchs and Jesus Christ, but the ceiling remained as intended: a dark blue with gilt stars, like the night sky.

Then came Michelangelo Buonarroti. Commissioned to paint only the twelve apostles on the ceiling, he spread his hands and composed 343 images, placing, in the centre of them all, what became the most famous of them all, The Creation of Adam. Twenty years later, he returned to turn the altar wall into The Last Judgement. Michelangelo’s venture beyond his brief is part striking for its inclusion of non-Biblical figures, some fictional, like the Ignudi, and some pagan, like the Sibyls: prophetesses said to have foretold the birth of a Saviour. In interpreting the reach of the Church, he chose, as one of the five Sibyls, an African. And so a sanctity cornered for a few reopened up for many.

Over the centuries, millions of faithful and tourists have come to the Vatican to step onto the floor of the chapel, built to the 500-feet dimensions of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem, and look up into its fully peopled, stunningly detailed world: vast enough to feel like being inside mythology. But nature’s light is unkind to art as its time is to mythology, and, for almost 40 years now, the windows have been permanently shut and the interiors lit by the evenness of LEDs. In the brighter kindle, eyes widen even more: here are the histories and analogies, the faiths and glories, the bedrock of Christianity embedded, colourfully, in stone.

On the long, frigid morning of April 18, 2005, a trail of cardinals, those princes of the Church belonging to its most senior college, filed into the Sistine Chapel. Their colours were bright but their faces were dark. They wore white cassocks and scarlet skullcaps and capes, the scarlet signifying the Blood of Christ. Two weeks and two days before, the pope had died, John Paul II, and, ten days before, he had been buried, and now they were moving into the first conclave since 1978, to elect his successor. There were 115 cardinals present, the largest ever number of electors. As they walked in the Roman cold, they chanted in their twos the Litany of the Saints. They sang “Veni, Creator Spiritus.” A request for the Holy Spirit’s assistance in the great decision ahead. Once they were inside, to take their oaths before The Last Judgement, the chapel doors were shut.

Outside, in the curved basilica arms of St. Peter’s Square, a great crowd had gathered; an estimated one million pilgrims praying, flying their national flags, waiting for the sign from the chapel chimney: black smoke to show the cardinals had not yet decided, white smoke to show there was a new pontiff; after which the cardinal proto-deacon would appear on the balcony and proclaim, in Latin, “Habemus Papam!” We have a pope!

All over the world, tens of millions, only a fraction of the one billion Catholics, watched on TV. But that Monday evening, black smoke went up from the chapel chimney.

That night, in faraway Nigeria, in the city of Aba in the country’s southeast, a young religious brother stood in a kiosk on a quiet bent street named Asa Triangle, in the Block Rosary Crusade center called Our Lady of Fatima, and described the magnitude of what was happening in Rome. The kiosk was filled with candlelight, a shine of hope. And in the presence of the large crucifix and images of an agonizing Christ’s Stations of the Cross, there, under a ceiling of rusting zinc and rotting wood, eleven-year-old me padded himself with expectation. The brother said, in our native Igbo, “K’anyi yo ayiyo maka Francis Cardinal Arinze, ka o wuru the first African pope.”

The words of the young brother were the words on the streets, the words in the newspapers, the wants on TV. Arinze, the most senior African and Black cardinal, was papabile, a candidate for the Papacy: he was, for some bookmakers, the favourite. For years, there was growing thought that the Church might look to Africa for the heir of St. Peter, might choose a Black pope. The commentary was, in fact, a larger one of European hegemony. Of the 264 previous Bishops of Rome, only three are documented as African, all Berbers, and each made epochal contributions: St. Victor I, reigning from 183 to 203, decreed that Easter be celebrated on Sundays and replaced Greek with Latin as the official language of the Church; St. Miltiades, who was possibly Black, during whose pontificate, from 311 to 314, Christianity became legal in the Roman Empire; and St. Gelasius I, a prolific writer who, in his papacy from 492 to 496, regulated what became the canonical books of the Bible, shaped the preeminence of the Roman See in Church affairs, and was the first to be called “Vicar of Christ.” In the last few centuries, the modern Church had not had a pope from Africa or one ever from South America, the two continents where it had grown the most, and its European dynasty was, in fact, an Italian one. If Asia was the Church’s origin and Europe was its receding present, then Africa and South America were its future.

The papal conclave of 2005 was the shortest in history, lasting only two days, and at its end, after four rounds of voting, the Dean of the College of Cardinals, a German, Joseph Ratzinger, received the necessary two-thirds majority and became Pope Benedict XVI.

As Prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, the Vatican’s voice of liturgical regulations with clergy and laity, Francis Cardinal Arinze was, at the time of the conclave, the fourth highest ranking official of the Roman Curia, the governing body of the Catholic Church. His reputation as a diplomat and advocate was built on decades of teaching and apostolicism in Nigeria, during and after the Biafran War, and working across religious divides there and on the global stage, with African Traditionalists, Muslims, Jews, Hinduists, Shintoists, Buddhists, Confucianists, and Bahá’ís, and disseminating in his books and sermons a vision of neo-traditionalism that appealed to the Church’s conservative majority. The books, exploring subjects ranging from catechism to pastoral responsibility to Marian devotion, are not academized treatises on the indecipherable but practical solutions to everyday struggles of faith. He was in their pages as he was on the pulpit: a friend to the laity, a relatable guide, at once a defender of cultural peculiarities and a proponent of fidelity to the unifying, foundational virtues of worship. In 1999, the International Council of Christians and Jews awarded him its highest honour, the Interfaith Gold Medallion.

For decades, he was a confidante of the late John Paul II, who elevated him to cardinal, appointed him to a career-making office in the Roman Curia, as Prefect of the Pontifical Council for Inter-religious Dialogue, through which he served as one of three President Delegates of the Special Assembly for Africa of the Synod of Bishops, before moving him to the even higher Congregation for Divine Worship. The prefectures were assignments of great visibility, and, with his persuasive work and personality, elevated him as one of the deepest respected voices of Catholic reason. They also brought him to TV. It is estimated that he produced over 1,700 TV programs with the Apostolate for Family Consecration, covering the Pope’s encyclicals and apostolic letters, as well as Vatican II. He regularly appeared on Familyland TV, a station broadcast in select countries in the five continents. The year before the death of John Paul II, he, in 2004, on behalf of the pope as prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship, signed the Redemptionis Sacramentum, an instruction on how to celebrate Mass and adore the Blessed Sacrament.

It took grit and heart and mental clarity, but Cardinal Arinze’s rise was also attended by a clock of history. He was almost 33 when he became the youngest Catholic bishop in the world, and 53 when he became cardinal, and, at 73, it seemed that he could become pope. His Africanness, his understanding of the multicultural shards of colonialism, was perceived as a base for his ability to look towards a more modern Church, blending local cultures with Latin traditions. He seemed to be what the Church needed: a dependable bridge in a time of change.

A steady hand is a quality that the Church values above all else. Upon accession, one of the first appointments of Benedict XVI was to reconfirm Cardinal Arinze as head of the Church’s liturgy department. In addition, the new pontiff had a new task for him: a suburbicarian diocesan responsibility that he himself had just vacated after becoming pope, a role traditionally held by papabiles: Benedict XVI elevated Cardinal Arinze to Cardinal Bishop of Velletri-Segni.

All these made it natural that when Benedict XVI abdicated, only eight years later, the Church laity and commentators, in greater need of a steady hand than ever, turned their gazes, again, towards Cardinal Arinze. The chatter this time even louder. Although he was 80 and had resigned his prefecture and was no longer a voting cardinal, he remained eligible to be elected. Ultimately, his peers chose Jorge Cardinal Bergoglio, an Argentine who had come second to Cardinal Ratzinger in 2005, who became Pope Francis I, the first South American pontiff. For commentators, it was an equal victory that, for the first time in centuries, the pope had come not yet again from Europe but from a continent where, like in Africa, the Church was growing, its future more certain.

Eleven years have passed since the conclave of 2013 and nineteen since that of 2005, and, in early February of this year, His Eminence, reputed for his honesty yet seasoned in politely parrying prying questions from the media, gives a warm laugh before he answers me. “You will have to distinguish between the opinion of journalists and commentators and Divine Providence,” he says, his Igbo accent uncorrupted by Europeanisms. “The journalists were not members of God’s Advisory Council. And some Nigerians began to take it very seriously.”

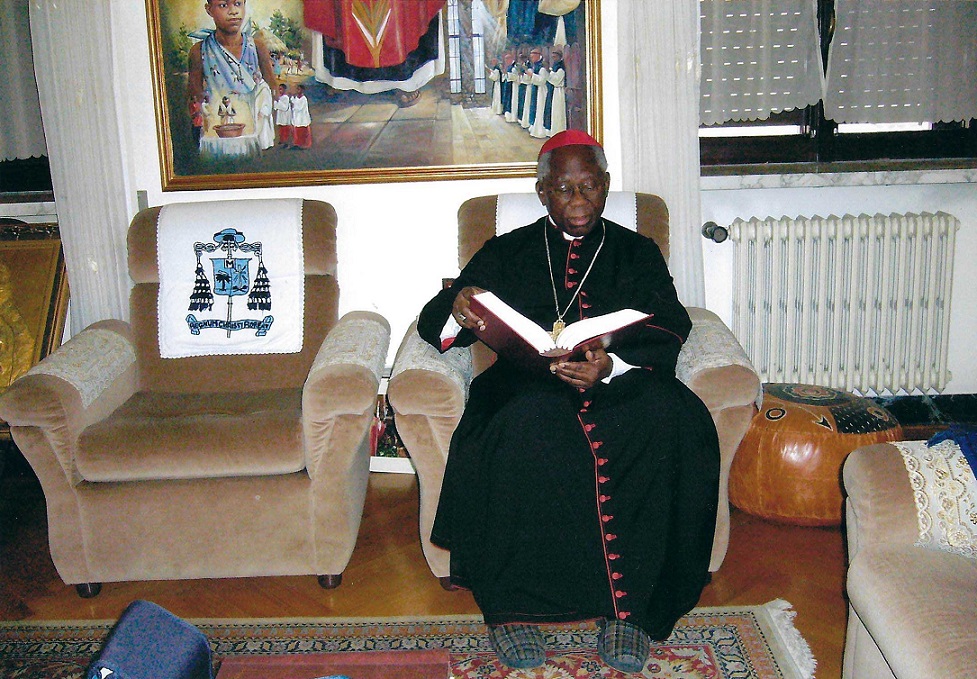

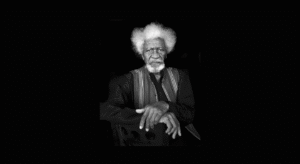

He is in black cassock and cape and red skull cap, and behind him looms St. Peter’s Basilica: an electronic background. On Zoom with him, off camera, is his private secretary, Father Anthony Ezeugo, who received my enquiry and set up the interview.

His Eminence’s glasses, gold-rimmed, reflecting light as he thinks. “You ask me, was it amusing to me?” Hand goes to chin. “I say, to some extent, because I didn’t think it would happen. But there was a serious side to it. It means that these people and the journalists are no fools. It means that they think that the Church in Nigeria is growing and is contributing to the universal mission, so much so that they could think of a bishop from Nigeria being elected. So that is a credit to Nigeria. So that part is clear there. There was also the funny part when I would be travelling, months after at the customs, when they saw my passport, they said, ‘Oh, that’s that man. Let’s approve him quickly.’ So for me, that was just getting attention. For the wrong reasons, however.”

At 91 years old, His Eminence is ebullient and engaged. His warmth comes through the screen, and when he speaks, in the 30 minutes we do, so does his humour, alert and accentuated. It is, I suspect, a parity of solemnity and levity that he, in 66 years of priesthood and 39 as a cardinal, has scaffolded navigating hitherto uncharted waters. He speaks, too, in topic phrasing, ending most of his answers by reconnecting to my questions.

“Look,” he continues, “a cardinal would have been presumed to have something wrong with him if, going into the conclave, he believed that he would be elected. And if he was not elected and he was disappointed, then he would not be normal. That would actually be good proof that he should not be elected. No cardinal who is normal would expect to be elected or not be happy when a very capable cardinal is, like Cardinal Ratzinger. He would be in joy and in prayer. That was our climate. So I think this covers most of what you are asking.”

It is a lot that I have asked, the lot that I have had in mind since that night at the Block Rosary Crusade centre in Aba, and most of it His Eminence steers away with the amused indulgence of a grandfather at a child’s curiosity about a world carefully cultivated to remain beyond reach.

“But it is gratitude also to our missionaries,” he adds, “considering that two hundred years ago we hadn’t the Catholic Church in Nigeria yet.”

II.

May the Land Bring Salvation

Christianity arrived in Africa around the same period that it did Europe, in the first flush of evangelization following the Crucifixion of Christ. The dates are unsettled, but sources claim that, between 42 and 61 A.D., as St. Paul sent his letters to the Greek communities, St. Mark, an African Jew born in Libya and purported to have later written one of the Synoptic Gospels, left Jerusalem and came to Alexandria and founded the Egyptian Church.

By the second century, it had spread west, along the North African Mediterranean coast, to Carthage and Libya, home of the three Berber popes, and south, too, up the Nile, to Nubia. Alexandria became one of the three main apostolic sees of the early Church, alongside Rome and Antioch, and later part of the pentarchy, when that governing structure expanded to include Constantinople and Jerusalem. In either the year 333 or 340 — because the Ethiopian calendar date of 333 E.C. is seven years behind the Gregorian one of 333 A.D. which we use, and it is unresolved which was used as marker — the Kingdom of Aksum, in modern-day Ethiopia, adopted Christianity as the state religion. This was almost 50 years before the Roman Empire officialized Nicene Christianity. So began the collation, in their native language of Ge’ez, of what became known as the Ethiopian Bible, the oldest version of the Bible, with more books than every other, including the Vulgate Version, released in 400, and the King James Version, of 1611.

North African Christianity had so grown by the fifth century that at the Council of Carthage, in 411, there were seats for an estimated 1,371 bishops from the region, split equally between Catholic and separatist Donatist loyalties. African theologians and philosophers played seminal roles in shaping the Church, including the doctrine of the Trinity and the Nicene and Athanasian Creeds, chief among them St. Augustine, St. Pantaenus, Origen Adamantius, Clement, Athanasius the Confessor, Pachomius the Great, and Cyprian of Carthage. The theological dissents of Arianism and Donatism, and the Muslim invasion of North Africa and subsequent similarities between Arab and native cultures, upended that progress. For the next few centuries, as Christianity took deeper roots in Europe, it was supplanted in North Africa, with Ethiopia the only Christian state left. It would be almost a thousand years before a second rise of African Christianity, in most of the continent south of the Sahara, through the colonialists arriving via the Atlantic Ocean, bringing a version that had been Europeanized, retooled for the economics of conquest.

The religion first reached present-day Nigeria in 1515, through the Portuguese at the Kingdom of Benin, but it was centuries later, in 1857, as the British assailed the hinterland, that it breached Igboland through the Church Missionary Society (C.M.S.) — the second Christian group to arrive the old Eastern Region following the Scottish Presbyterian Mission in Calabar in 1846. As the West African Company (later the Royal Niger Company) competed with the French and the Germans for territory, persuading and taxing and smashing towns into submission, sacking Onitsha in 1879, a third group came. Four French priests of the Spiritan order sailed up the Niger and, on December 5, 1885, berthed at the battered city.

The Berlin Conference had just partitioned Africa among European powers, and rivalry ensued. The Spiritans were led by Joseph Lutz, who, in the battle of conversion tactics, capitalized on his medical knowledge to treat their hosts and win their sympathy for the Roman Catholic Mission (R.C.M.). Though bristling at British interference in their religion, Onitsha people opened to the Catholics partly due to European medicine. Conflict within the C.M.S., during which many Africans were removed from their positions, drove more converts to the R.C.M. As the Royal Niger Company’s brutal administration earned it hostility, the R.C.M., by being on the side of the people unlike the “neutral” C.M.S., only grew, breaking Protestant hold and spreading to a trail of towns in the hinterland. Soon, it reached a small town called Eziowelle, in present-day Anambra State.

Like all Igbo people before the British invasion, the majority of Ndi Eziowelle followed the Igbo traditional cosmogony: a polytheistic system called Odinani, translatable as It Is in the Land, revolving around local and elemental deities, each with their worshippers, but recognizing the supremacy of Chukwu, the great God. But an increasing number of them were turning, not merely because the missionaries’ story of a Son of God dying for the sins of the world was compelling, but because the times had changed. The foreigners had stolen their lands with guns in one hand and a Bible in the other, a Bible pointing to a school, a new way of learning. They saw, in the colonialists’ enforcement of unpaid labour and the missionaries’ preaching of forgiveness, a brazen hypocrisy. But they saw, too, that the ones who learned from the white man took on manners of appearance and speech, including showing off their incomprehensible language, English.

Among Eziowelle people were a couple who, eventually, were baptized Joseph and Bernardette Arinze, but, at the time, stuck to the Igbo religion while watching events from their mud-brick bungalow, with curiosity. On November 1, 1932, their third son, of eventual seven children, was born. They named him Anizoba, May the Land Continue to Save, an invocation of Ani, the goddess of purity and the most powerful of the Igbo deities. All their children went to the Catholic mission school at Eziowelle, and later at St. Anthony Primary School, Dunukofia.

Young Anizoba Arinze had never seen a priest before. Then one evening, the converts were told that a priest was on his way. But the person who came to them was not a white man but an Igbo man: a gentle smiling figure wearing glasses. His name was Michael Iwene Tansi and he spoke to them with convincing ease. The boy was swayed and his life changed, and he saw in the young priest the light to follow. In 1941, nine-year-old Anizoba was baptized by Tansi and took the name Francis. It was Tansi who administered and shaped Francis’ first experiences of the sacraments: Tansi who heard his first Confession and gave him his first Holy Communion. He became a Mass Server in 1945, Tansi’s last year at the parish. It was the bloom of a deep connection between the two men, and, even after he left the parish, Tansi remained to him both spiritual father and friend.

At St. Anthony’s, Francis’ teachers were aware of his gifts. For him, it was priesthood and junior seminary. Dreading how his parents might take the news, he kept it from them at first; he sat for and passed the examination, got admission to the Junior Seminary, Nnewi, where he was one of its first students, and then told his mother that he wanted to be a priest. After some difficulty, she was convinced.

“No,” his father said.

He expected Francis to have a wife and family, and he was not enamoured of everything Catholic. “Why should you go into a profession where you will be hearing evil things that people do in your two ears?” he asked. “That is not good for you.” He would not allow his son to become one of those people that the community contributed bananas and eggs for. He thought it funny: grown men eating eggs and bananas.

Francis’ siblings pleaded and their father refused. To Francis, he offered money to buy a pencil: the boy could send the pencil to the rector and ask him to strike through his name in the register. Francis turned to the new parish priest for help. The intercession of Father Mark Unegbu succeeded. He threatened to withdraw Francis’ siblings from school but their father still said no: let them all return home and resume work in the farm. Eventually, he yielded.

In 1947, Francis, aged 15, went to the Junior Seminary. Like other seminarians from poor means, he travelled home on foot during the holidays, a 10-kilometre-trek from Nnewi to Eziowelle, with his luggage on his head. By the time he obtained his Cambridge School Certificate in 1950, his father, seeing how much he took to it, had begun to encourage him. In the two subsequent years he taught at the Junior Seminary, the school, in 1952, changed its name to All Hallows Seminary and was moved to Onitsha. His string of exceptional academic results won him exemption from the prized London Matriculation and led his instructors at Bigard Memorial Seminary, Enugu, where he’d gone to study philosophy, to earmark him for studies in Rome.

He arrived Pontifical Urban University, Rome, in September 1955, and accrued his bachelor’s, master’s, and summa cum laude doctorate in theology. It was in Rome that he was ordained a priest, on November 23, 1958. He was 25. Alongside him was another Nigerian, a year older: Anthony Okonkwo Gbuji. It was a winter dawn and they stood in the chapel of Urban College and took their Holy Orders from Gregorio Cardinal Agagianian, the Patriarch of Cilicia. Father Arinze said his first Mass the next day, in the Basilica of St. Mary Major, and his second, in a Carmelite Monastery.

It was in Rome, too, that he put in writing in his studies his ideas of intercultural dialogue. Born in an era in flux, he had, by his familiarity with his parents’ religion even as he grew into a different one, seen points of comparison. The Igbo religion was the old way, local and familiar, and Christianity was the new, foreign and strange, and in a central tenet of Catholicism lay a similarity: the service of sacrifice. He submitted it as part of his doctoral thesis: Igbo Sacrifice as an Introduction to the Catechesis of Holy Mass. His view, at the time, became a point of departure for scholars, and, a decade later, was published by the Ibadan University Press, with the title Sacrifice in Ibo Religion.

It was 1960 and Nigeria was independent, and, his doctorate over and priesthood beginning, Father Francis Arinze returned home, with a strong reputation. He was a lecturer in liturgy, logic, and basic philosophy at Bigard, and, two years later, Catholic Education Secretary in Enugu, assigned by Bishop John Cross Anyogu to represent the Church with the government of the Eastern Region. The bishop sent him to the Institute of Education, University of London. There, his professor, P.C. Evans, wrote afterwards: I am sure that a man of Father Arinze’s quality must be marked out for great things. The education office had primed him for a major responsibility.

Meanwhile, in Rome, the Second Vatican Council — the 21st ecumenical council in Church history — began in 1962. For Pope John XXIII, it was an opportunity for “Aggiornamento” — Italian for updating — to bring the Church in lockstep with a post-World War II century, and to do this he invited all Catholic bishops and heads of men’s religious orders around the world. “The Church should never depart from the sacred treasure of truth inherited from the Fathers,” he told them. “But at the same time, she must ever look to the present, to the new conditions and the new forms of life introduced into the modern world.” John XXIII died in June of 1963. The cardinals elected Paul VI weeks later, and the Council resumed, for the next three years.

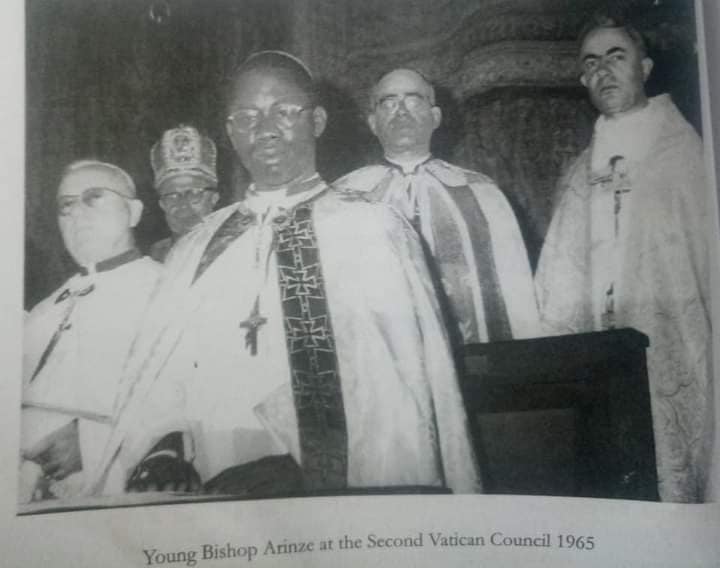

Five months before the close of Vatican II, Pope Paul VI made a set of appointments that came as a surprise to Arinze. On July 6, 1965, the pope appointed him Titular Bishop — a title of a diocese that no longer exists and hence came with no jurisdiction — of Fissianna, a region in Tunisia. (Fissiana last had a bishop in 411, the year of the Council of Carthage, when African Christianity thrived.) More importantly, the pontiff appointed him co-adjutor Bishop of Onitsha, tasking him with assisting the Irish archbishop, Charles Heerey, who had given him the Sacrament of Confirmation. A month later, Archbishop Heerey consecrated him and, at 32, he became the youngest bishop in the world. There was no time to let it all sink in. Bishop Arinze’s new job meant expanded responsibility, and, two weeks later, in September, he was on a plane for Rome, to attend Vatican II.

The last of the four council sessions was in progress when the young bishop joined. A senior bishop looked at him. “Are you a seminarian?”

Arinze, with his unfailing sense of humour, replied, “I was. But not now.”

He understood the risk the Church took in consecrating a young bishop. When the Council commenced in 1962, he was a lecturer in philosophy in Enugu, and now, three years later, it was ending, and here he was, back in Rome, the youngest in attendance, standing with the fathers of the Church. His ascent from priesthood to bishopric had taken only seven years. It would have been shocking for him.

His youth was not the only observation staring Bishop Arinze in the face; there were his Blackness and Africanness. Of the roughly 2,625 council fathers drawn from 79 countries, the majority were European and American; next were Asian and Oceanian; with a tenth, around 260 bishops, from Africa. The timing of the Council coincided with the peak of nationalism and independence in the continent, so the various national Churches were still run by British, French, Portuguese, and Dutch missionaries. Among those representing Africa, only 61 were African and not all were Black. Their leader was Laurean Rugambwa of Tanzania, the first native-African Catholic cardinal and the first Black cardinal elector, and he made his voice, however minor, heard, pushing for the Roman Curia to be internationalized and encouraging cooperation with other Christians.

The reforms of Vatican II made it the most important event in Catholic history since the Reformation; for some, since the schism of the Western and Eastern Churches. Priests could now say Mass in English and local languages and not just Latin, and they would now face, not back, the congregation. Music with local colour was now allowed. Laity could now lead scripture readings, sit on parish councils and diocesan boards, and hold administrative positions in their parish. The changes reduced the gaps between the Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant Churches, on the one hand, and between the Church and Islam and Judaism, on the other.

The Church’s new embrace of inculturation would have stood out the most for young Bishop Arinze; that fact that a view he held in his doctoral thesis five years before was already being discussed by many bishops, and had, finally, reached its time. He appended his signature to 10 of the Council’s 16 documents, ranging from treatises on missionary activity, priestly life, and pastoral office, to exhortations on the laity, religious freedom, and interreligious relations.

Now, as a retired cardinal looking back, when I ask if the open-mindedness of Vatican II aided the subsequent growth of the Church in Africa or if the growth would have happened regardless, he tells me that it helped.

“Granted, every change in religion affects people’s habits, what they are accustomed to,” he says. “But when you consider the whole situation, the introduction of local languages in church worship helped. When people understand what they are saying or singing or praying, perhaps they do a bit better. The bigger aspect is bringing the worship nearer to the people, bringing the people nearer to the worship, so that they can say, ‘This Mass is our Mass.’ It isn’t just the Mass of the priest.”

(The impact of Vatican II on African Catholicism is contested. The continent was an ideological afterthought at the event, representatives had little time to scratch the palimpsest of theological precedence, and doctrinal deliberations were too Eurocentric for even the expatriate bishops. Organized as they remained, the African contingent came away with not only tailoring worship to local cultures but also, scholars have asserted, a drive to grow an African theology — which opened tolerance for African Traditional Religions.)

The Council ended in December of 1965, by which time Bishop Arinze had considered how the Church operated in other countries and pondered ideas with other council fathers. One of those he met was Karol Josef Wojtyla, a Polish priest whose own rise mirrored his. The year Arinze was ordained, in 1958, Wojtyla was consecrated Auxiliary Bishop of Krakow, in Poland. The year before Arinze was consecrated, in 1964, Wojtyla became Archbishop of Krakow. During the Council sessions, Cardinal Wojtyla helped shape two important documents, “Decree on Religious Freedom” and “Pastoral Constitution of the Church in the Modern World.” Arinze did not know it then, but it would be the most consequential meeting of his clerical career.

Back in Nigeria, his task was to explain the new approach to the laity, and, duly, he travelled around, doing so. In February of 1967, Archbishop Heerey, the last white man to hold the seat of Onitsha, died. In June, Bishop Arinze became Archbishop of Onitsha and custodian of a Metropolitan See covering the entire old Eastern Nigeria region. The same month, his friend, Archbishop Wojtyla, was created cardinal.

In Onitsha, the archdiocese crackled with grief and uncertainty. Nigeria was hurtling towards chaos. The military coup of the year before, led by young officers who were mostly Igbo, was answered with a counter coup, planned by Hausa-Fulani soldiers, and then with an ethnic pogrom, an estimated 30,000 Igbo men, women, and children slaughtered in the north of the country. A religious complication: the Igbo were mostly Christian and the Northerners were mostly Muslim. Subsequent talks failed. The military government of the Eastern Region, homeland of the Igbo and minority ethnicities including the Ijaw and the Efik, seceded and declared a State of Biafra. The new territory was the Metropolitan See of Onitsha. A month later, on July 6, the Federal Government of Nigeria moved against the former Eastern Region, launching a savage civil war.

Onitsha Archdiocese, at the time of Heerey’s death, relied mostly on missionaries, Irish Spiritan priests, and many expected one of them to be named his successor. Instead, it was Arinze, still 35 and not a Spiritan. The Biafran War dispelled any doubts of his leadership. The Nigerian military offensive, with heavy bombing, triggered a major refugee crisis, and Archbishop Arinze was forced to flee Onitsha. He carried with him all Church documents, of clergy, laity, teachers, and settled in Adazi, and later in Amichi.

“War is a terrible thing,” he tells me. “It brings suffering. It brings hardship. It also brings along an opportunity for human beings to be at their best, and for a few people to bring out their worst performance.” He remembers starvation, the depleted meals. “War teaches us to do without things we consider very important. Some people think that taking their tea or coffee, they must have sugar. Not necessarily. And under war conditions, you might not have sugar or even enough salt.”

Much of what he tells me hints at the suffering of his parishioners. Watching and experiencing it provoked for him and the archdiocese a rethink of the dimensions of pastoral care, what it should mean for the body. “We think of” — he lists — “we go to Mass, baptize people, give them Holy Communion, visit their sick, but also give them food, to the needy, to the hungry, looking for housing, for refugees, looking for minimum cover for those without clothes. In helping people in extreme situations, you share with them. They never forget it.”

The grieving, hungry, displaced, sick laity of Biafra was under blockade, and people were dying more from hunger than from bombs and massacres. Hope was essential and he needed to be the pillar of it. He was not alone. European missionaries who did not flee the burning country exerted themselves, under Arinze’s supervision, distributing relief materials — food, medication, clothes — flown in by Caritas International. “There were women who gave birth to children during the war,” he recalls. “Some named the children Caritas.”

The Church is not only liturgy, he says. It is also assistance to the needy: “Practical help, because man is body and soul.” He cites another example. “For those who had to run away during the war, without time to collect their property, many dioceses began what we now call the Justice, Peace, and Development Department. So you can see. There were many lessons from the war. We learned to do without things. We learned to manage. We learned to be satisfied with less than the ideal.”

The Church’s prominent role in providing for Biafran refugees, and Arinze’s care in disentangling the archdiocese from politics, rankled the Federal Government of Nigeria. After the war formally ended on January 15, 1970, with the surrender of Biafra and an estimated three million Igbo and Eastern ethnic minority people dead, General Yakubu Gowon’s regime pursued a covert socioeconomic war of attrition against the vanquished. Gowon, an Anglican Christian whose war was backed by the Anglican British Empire and the Communist Soviet Union, deported all 50 foreign missionaries in the former Biafra, and enacted policies that archdiocesan records would later describe as “anti-Christian.” Archbishop Arinze traveled to Lagos, to the military headquarters at Dodan Barracks, and pleaded with the general not to deport the missionaries. Not much came out of it. Forced back into the fold — much of its cities in ruin, industries devastated, chances of quick recovery sabotaged by ruinous economic policies, and the bank accounts of Igbo people robbed by Nigeria and each person given £20 to begin life anew — the former Eastern Region was struck by immediate poverty.

Reliant on laity generosity, rebuilding was daunting for the Catholic Church, especially with the missionaries gone and indigenous clergy numbering only 33. The archdiocesan records that Arinze preserved were instrumental, especially for teachers who lost their certificates in the war but needed to be reinstated. He streamlined the Church to a frugal budget and the clergy to a simpler lifestyle. He introduced a monthly day of recollection and tasked parishes with vocation drives, empowering committees and councils on his frequent pastoral visits, and, eventually, creating, alongside parallel groups for men, girls, and boys, the influential Catholic Women’s Organisation.

In 1972, the pope conferred him with his pallium, the symbol of archbishopric authority, which was postponed due to the war. In 1975, he founded a religious institute, the Congregation of the Brothers of St. Stephen, in Onitsha, and, in 1978, erected a monastery that became St. Scholastica Benedictine Abbey, Umuoji. Later, a second monastery, Our Lady of the Angels Cistercian Monastery, Nsugbe, was built for men. Each year, he administered the Sacrament of Confirmation to an estimated 14,000 people. In time, with two minor seminaries in place, the archdiocese had a few hundred candidates for priesthood, and a restored future.

The daily devastation of war now behind, Arinze settled enough to collect his thoughts in writing. He sent out pastoral letters on a range of social issues: justice for the poor, the rights of children; and on temporal matters: the Christian family, Christian attitudes to work, money, and politics, Nigerian culture meeting the Church; and on spiritual questions: chastity, the Holy Eucharist. The letters, motivational during Lent, built on the decisions of Vatican II, and led to parishes creating annual quizzes based on them.

The wider Nigerian Church was growing, placing itself on the map. One of its champions was Dominic Ekandem, another leader of the Church during the war. He had to his name a series of firsts: in 1947, the first Catholic priest from the old Calabar province; in 1953, the first native West African Catholic bishop. He was Auxiliary Bishop of Calabar, and later Bishop of Ikot Ekpene, and, much later, would become Archbishop of Abuja. He was at Ikot Ekpene when, on May 24, 1976, Pope Paul VI created him cardinal, the first from Nigeria.

Soon afterwards, in Rome, the Church underwent a strange year. It was 1978, August 6, when Pope Paul VI died. Twenty days later, an Italian, Albino Cardinal Luciani, the Patriarch of Venice, succeeded him and took the name John Paul I, the first pontiff to have two names, his way of honoring the two popes before him, John XVII, who consecrated him bishop, and Paul VI, who created him cardinal. John Paul I had been consecrated bishop in 1958, the year that Arinze was ordained a priest, and created cardinal in 1973, and only five years later became pope. His reign was short, 33 days before he died of heart attack. The papal conclave elected Cardinal Wojtyla, who took the name Pope John Paul II, in honour of his predecessor. For the first time since 1605, the Church went through three popes in one year.

For the Nigerian Church, rebuilding was still in progress. Although the war was partly prosecuted on ethnic and religious differences, Arinze had managed to create a communion not just with Catholic bishops in his metropolitan see in the east but also with those in the north and west of the country. In 1979, the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of Nigeria elected him president. At the United Bible Society, he became vice president for Africa. And then, in February of 1982, his old friend Pope John Paul II visited Nigeria for the first time, on his tenth apostolic voyage, which also took him to Gabon, Benin, and Equatorial Guinea.

In Onitsha, the pontiff addressed thousands. “Dear young men and women of Nigeria, this afternoon, the Pope belongs to you!” he declared. The five-day visit saw him visit Lagos, where he met with President Shehu Shagari, and Kaduna, where he ordained priests and Muslim leaders, and, after the Angelus, consecrated the country to the Blessed Virgin Mary. It was, for Nigerian Catholicism which was not even yet 200 hundred years old, the supreme buoy. After the papal tour, Arinze resumed his work as archbishop, writing pastoral letters, inviting the laity to ponder the times.

In 1984, he received a letter of his own. The pope had decided that his leadership, his management of minute resources to attain results and his ability to navigate religious divides in a harsh political environment, was what the Church needed on the global stage. He was summoned to the Vatican, to the Roman Curia, to become Pro-President of the Secretariat for Non-Christian Religions (later renamed the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue and, now, the Dicastery for Interreligious Dialogue). What he had done for the Nigerian Church, he was now expected to do for the Vatican. A delegation from the Archdiocese of Onitsha followed him to Rome to pray for him. He had served them for 17 years.

On May 25, 1985, Pope John Paul II created Arinze cardinal. He was named cardinal-deacon of San Giovanni della Pigna. Again, a delegation arrived from Onitsha to celebrate him. At 53, he was one of the youngest members of the College of Cardinals, and the second ever from Nigeria.

When I point out the chronological significance, that he was created cardinal exactly 100 years after Catholic missionaries arrived Igboland, His Eminence’s brows furrow in doubt. Off camera, Father Ezeugo asks what I mean, that I clarify. I repeat it, draw out the years: 1885, 1985. His Eminence’s face flits from doubt to realisation to surprise.

“That’s true,” Father Ezeugo says slowly. “We have never thought about that.”

III.

“The African soul looking for God”

Local cultures flavoured African Catholicism with a tone and intimacy lacking in the rest of the global Church. Describing the Nigerian Church in an interview, Cardinal Arinze pointed out the values of community and celebration, how Europeans and Americans think that Africans dance all the time when, really, what we do is putting our “mind, and body, and soul in the act,” which is expressed in how people move to the altar: “a bit left, a bit right. . . the whole body showing the joy in the giving.”

He highlighted, too, the healthy sense of responsibility from the laity. “For instance, if you have a seminarian who’s a little shaky, who’s engaged in some funny business, one of the ladies from the Catholic Women’s Organisation is going to know. One of the women could say to the parish priest, ‘Are you and the bishop actually going to ordain that young man a priest? Do you really want him to be a priest?’ That becomes an indication of what they think. That we are the Church, and if this young man is ordained, he’s going to work for us, so we have a say.” He added, “Our people, no matter how poor, they like to associate with others. It can be in joy or in sorrow. It can be a wedding. It can be a funeral. But the individual is never alone. That is a value very precious for the Church.”

Something else he said — that “Faith, being one, is incarnated in each culture” — made me think about Sacrifice in Ibo Religion. Does he see this as compatibility between Catholicism and African Traditional Religions?

“One needs to go carefully,” he begins, caution in his cadence. “Christianity is not a later edition of African Traditional Religions. No. But African Traditional Religion is the African soul looking for God. Because God made us for himself, and our souls are never at rest until they rest in God, said St. Augustine. So our ancestors, when nobody told them about Christ and the gospel, their souls were looking for God. They had ways of asking God, praying to God. That means, in the morning, the father in the family, in the name of the whole family, thanks the Almighty God, who lives in Heaven, for having kept them, giving them life; at night, he begs God to bless his wife and children, to keep them in good health. He prays for new young children to be born. So there are many elements in this religion.”

The cardinal is in professorial mode now. He’d written his dissertation “as an introduction to the case of the Christian sacrifice, the Mass,” he said. “But these people who were first evangelized from 1885, they did not come from a religious void. Their past had religion, prayer, God being superior to human beings. They also believed in spirits, good and bad. Not a bad preparation for Christianity, which believes in angels and in devils. And they believe, also, in life after death, and that what a person has done in this life has influence on what will happen to that person afterwards, which is like preparation for the gospel.”

He argues that these rites in the Igbo religion formed “a relationship in the ways of Divine providence”: the traditional prayer, priesthood, place of worship, sacrifice, thanksgiving, petition, the cleansing of abomination: they were all “part of preparation for Christianity.” And it was the native Christians, not the missionaries, who had this insight.

“The local Christians had a heavier duty to see the elements in their traditional religion and culture, which, providentially, in the ways of God, helped them to embrace the religion of Jesus Christ,” he explains. “Because grace in Christianity does not destroy nature in African Traditional Religion. Grace builds on nature, which means, the more we appreciate the African soul in his worship, the better placed we shall be to present Christianity so that, gradually, they would see that what their soul was looking for at four in the morning has been brought to them at midday.”

It was this idea that animated Sacrifice in Ibo Religion. “The God they had been looking for how to worship, what to offer him, that God has now, in Christianity, given us the sacrifice that he wants. Not cows, not goats, not fowls, but the sacrifice of His own son who took on human nature for love of us and for our salvation, who lived on Earth, preached for three years, suffered and died on the cross for us, and told the Apostles, ‘You go on celebrating what I am doing. Do this in commemoration of me.’ Isn’t it beautiful?”

It is: the way he has put it. His Eminence is beaming, and I am beaming, too, because, in the small space of our call, I feel like a new convert.

“Inculturation.” That is the word he says now, the word he begins to explain, the resolution from Vatican II: “Christianity did not come to destroy the cultures of various peoples but to assume what is good to retouch, what needs to be amended. Also, to reject what cannot be accepted, so that it is all the peoples of the world bringing their gifts to the City of Christ.” He compares it to the three Biblical magi bringing their gifts to the baby Lord Jesus: their gold, frankincense, and myrrh.

It is an understanding ingrained in him since the most important encounter of his life.

Michael Iwene Tansi had been a priest for four years when he baptized Arinze in 1941, but his path was so spiked by personal history that he might not have taken it at all. His parents worshipped in the Igbo Traditional Religion, his farmer father Tabansi and his mother Ejikwevi, of the small village of Igboezunu in the notable town of Aguleri. Aguleri had drawn the ire of the Royal Niger Company, and, in a raid that left houses burnt, animals killed, and people injured and killed, Tabansi was among the native men kidnapped by the British gunmen. Tabansi’s first son was born in September of 1903, and, aggrieved, he named him Iwegbunem, May Anger Not Consume Me, which, as the boy grew, was shortened to Iwene.

Tabansi’s intention: his son would receive the white man’s education, as vengeance for what they did to him. Instead, the young Tansi arrived school, was baptized Michael by Irish missionaries, worked as catechist and schoolteacher, and chose to become a priest. He went to St. Paul Seminary, Igbariam, in 1925, and was ordained in 1937, the first priest from Aguleri, under the Apostolic Vicariate of Onitsha-Owerri, headed by then Bishop Charles Heerey. He worked as parish vicar in Nnewi, until the transfer to Dunukofia, where, at St. Anthony Primary School, he met Arinze.

Perhaps in reaction to his father’s intended life of rancour, Tansi turned his priesthood into a channel for reconciliation. In 1945, he was transferred to Akpujiogu, a barely known town where he became its first parish priest. Four years later, he was posted to his hometown. By then, he was known for his dedication to the Sacred Heart and to the Blessed Virgin Mary, his provision for the poor, his advocacy for religious life, his commitment to traveling to the laity, his attention to preparing young girls for Christian marriage, and the countless hours he spent in the confessional, reconciling the faithful to God.

Tansi was known, too, for his keen political awareness, a consequence of that personal history. On a reported 1946 visit to Kaduna, northern Nigeria, in a homily in the now St. Joseph Cathedral, he was said to have asked the Hausa-speaking Northerners permission to address the majority Igbo worshippers in their native Igbo, and then he proceeded to caution the Igbo to respect their hosts. This was a year after the Jos riots of 1945, when the British egged on Northerners against the Igbo, a harbinger of the pogrom to come.

In 1950, the Apostolic Vicariate of Onitsha, which had been carved out of the Apostolic Vicariate of Onitsha-Owerri, was elevated to archdiocese, and Bishop Heerey to archbishop. On encouragement from Heerey, who hoped to establish a monastery in Onitsha, Tansi expressed interest in becoming a Trappist monk. It was an ironic choice given his predisposition to public service. That year, he went on pilgrimage to Rome, and from there to England, as an oblate, to the Abbey of Mount St. Bernard in Leicestershire, where he was the only African.

Entrenched in the Cistercian Rule of fraternity, silence, and solitude, he worked in the bookbindery and the refectory. For his novitiate name, he chose Cyprian, in honour of St. Cyprian of Carthage, the Berber theologian of the early Church. When his Trappist superiors changed plans to found a monastery in Nigeria, due to political tension in the country, and chose Cameroon instead, Tansi was disappointed, but he accepted it. The following year, on January 20, 1964, he died, of aortic aneurysm. He was 60.

When Arinze became Archbishop of Onitsha, he kept it in mind to spread the life of his spiritual father. Tansi’s example came to shape his own respect for Nigeria’s diverse ethnicities and religions even as the Biafran War destroyed his metropolitan see. In 1977, he went to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints and asked to see the Prefect, at the time an Italian cardinal, Corrado Bafile.

“Excuse me, Your Eminence,” Arinze, still learning the ropes, remembered saying to him. “I have a saint in Heaven. Please canonize him.”

“We do not canonize like that,” replied Cardinal Bafile.

“I do not know how you canonize,” Arinze said. “But my saint is in Heaven.”

Amused, Cardinal Bafile instructed his officials, “Tell this young archbishop how to start.”

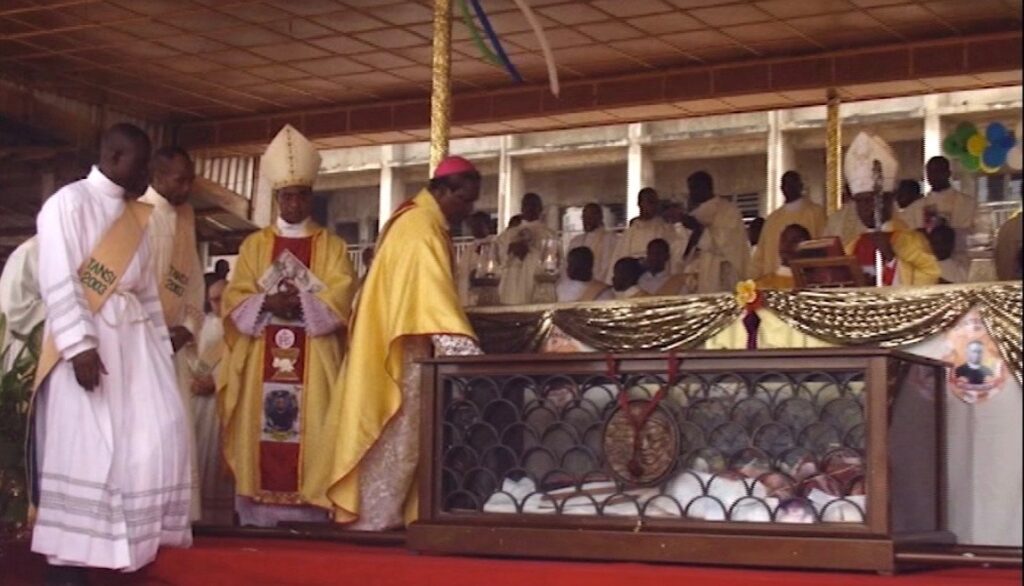

Presumed holiness is searched for, sealed by rarity. Arinze contacted the Diocese of Nottingham, where Tansi died, and appointed local postulators for Tansi’s cause. The arduous process — requiring countless interviews with people who knew the subject and could attest to their heroic virtues, and then proof of miracles attributable to intercession by the subject — was in progress by the time Pope John Paul II visited Nigeria in 1982, and Arinze followed it closely when he became a cardinal. In 1988, Tansi’s remains were exhumed from Mount St. Bernard Monastery, Leicestershire — his brains were said to still be “fresh” and “intact” — and interred at the then Most Holy Trinity Cathedral, Onitsha. In 1990, a young girl, afflicted with advanced cancer, was reported to have been healed through his intercession; she was said to have touched his coffin as it was returned to Onitsha. On July 11, 1995, Tansi was declared Venerable. Archbishop Albert Obiefuna of Onitsha formally recommended him for beatification, and Cardinal Arinze persuaded the ailing pope to visit Nigeria for the second time, for the ceremony.

It was March 22, 1998, a Sunday morning, and an estimated crowd of three million people gathered in Oba, near Nnewi, where Tansi had been parish vicar. Following Tansi’s life, the pope’s homily centered on reconciliation.

“Some of the people to whom he proclaimed the Gospel and administered the sacraments are here with us today — including Cardinal Francis Arinze, who was baptized by Father Tansi and received his first education in one of Father Tansi’s schools,” the pontiff said. “Blessed Cyprian Michael Tansi . . . received the gift of faith through the efforts of the missionaries, and taking the Christian way of life as his own he made it truly African and Nigerian. Father Tansi’s witness to the Gospel and to Christian charity is a spiritual gift which this local Church now offers to the Universal Church.” (In that spirit, the pope, urged by people, made a private appeal to the then military head of state General Sani Abacha, for the release of some 60 political detainees listed by the Civil Liberties Organization.)

Blessed Cyprian Michael Iwene Tansi remains the only West African to have been beatified by the Catholic Church. His feast day: January 20. In 2010, the Special Year of Priests, Nigerian bishops and priests proclaimed him a patron of its national priesthood. But the wait for canonization continues.

With Cardinal Arinze’s emphasis on the young age of the Nigerian Church, I asked him significant it was, at the time, to have someone on the path to canonization, someone from the first batch of converts.

“It meant: you are growing up; you have reached this stage,” he replied. “It was also encouragement and gratitude to the people who promoted the cause of beatification. When God works a miracle by the intercession of that person, it is the Divine seal, the Divine approval, that this person is in heaven. It was therefore a very encouraging moment for the church in Nigeria. For a person like me, obviously, because Blessed Tansi was the first priest that I ever knew, isn’t it therefore very encouraging if I can feel and I know that my master is now in the headquarters?”

The canonization process for Blessed Tansi should spur local African dioceses to propose more candidates, he adds. “Because it isn’t Rome that will go to all parts of the world to fish out those who practiced virtues to the heroic degree. It is the local church. When the local church begins such a process, then, with clearance and encouragement from Rome, gradually it can work.”

Two years after the young girl’s healing from cancer accelerated the beatification of Tansi, another young girl, in the small town of Aokpe, in Benue State, had a different presumed encounter of holiness. Christina Agbo was 12 years old in October of 1992 when, one morning, as she collected herbs in the field, she saw, she said, a beautiful woman attended by light, in a white gown and blue veil, afloat in the sky. The woman visited a few more times, and by 1994, a pilgrimage had begun to Our Lady Mediatrix of All Graces, and continued for the next ten years, thousands taking to heart her messages of prayer and penance.

The apparitions of Our Lady of Aokpe captured the Nigerian Catholic imagination because it reinforced — especially for Marian cultures like the Block Rosary Crusade organisation, which derived from the 1917 apparitions of Our Lady of Fatima — a local value. Because Marian devotion, in the Nigerian Church, is often challenged from within, the presence of such high-profile advocates as Cardinal Arinze serves to validate it. In 2017, he published a book, Marian Veneration: Firm Foundations.

“The Catholic Church is very careful in reported apparitions because our faith is based on the revelation given by Christ to the Apostles,” he replies. “And that revelation finalized when the last of the apostles died, John the Evangelist.”

He explains further: “There is no new revelation binding us. But God can appear, the Lord Jesus can appear, His Mother can appear to freshen us on one aspect or the other. That is the place of apparitions. The Catholic Church goes carefully. If there is a report that our Blessed Mother appeared, the local Church chooses wise people to look into it: theologians, psychologists, medical doctors. Wise people interview all the people so that you distinguish between a real apparition from heaven and the fruit of somebody’s fertile imagination. The committee may say, ‘We cannot tell whether this is from heaven or not,’ or they can say, ‘This one is not from heaven.’ So the bishop works on it. At some stage he may have to refer it to Rome. Even when the apparition is certain, like Lourdes or Fatima, the Catholic Church does not oblige Catholics to believe in them. But it helps, and therefore people go on pilgrimage.”

I note to him that the apparitions of Aokpe overlapped with the beatification of Tansi and the cardinal gives me a querying look. “You spoke as if it were connected to the beatification of Blessed Tansi. I do not know.” He generalizes his explanation: “But we have all the fundamentals of our faith in the Bible. And especially in the gospels. You will therefore have to rely on the local bishop. Has he set up a committee? Have they studied it? If so, what was the result? The bishop must look after the faith of the people and not allow it to be hijacked by a local enthusiast who doesn’t distinguish between what he saw in sleep and a real apparition from Heaven.”

IV.

“An Apostle in the grand tradition of the first Paul”

His Eminence is diplomatic but also blunt. What many high-ranking Church officials might dance around, he points at and aims. He keeps in mind to speak to the purpose of the common people, breaking down complex teachings and relating them to their ways of worship, and, in dispensing with the learned, ceremonial language that has kept the laity at bay and rendered the clergy not so much mysterious as beyond reach, he won their ears. In 2018, he published The Evangelizing Parish, enjoining the Church to return to its communal roots, for the clergy to seek service and for the laity to seek to contribute. His directness has endeared him to conservative Catholics in the West, who view him, an African who was not born Catholic but helped its spread in a newly converted continent, as a bringer of clarity to a faith muddied by liberal politics and ideologies. The cardinal, though, sees himself as merely adhering to common sense.

Over the decades, he has waded into a lot of debates. On some subjects, he is humane. When the wave of refugee immigration rose, Africans and Arabs striving to Europe and Latin Americans to the USA, he noted that it is ideal for one to stay in their country but that arms sales, and subsequent insecurity, are a direct factor, and that it is a human right to migrate, and thank-you to those who welcome migrants.

On a few, he is reticent. He believes that not all guitar music is good for church; that the solution to a lack of priests in remote areas, like the Amazon, is not for priests to get married but for dioceses with more priests to send theirs abroad; that it is a psychological mistake, though not a dogmatic one, for worshippers to receive Holy Communion in their hands and not on the tongue; that priestly celibacy, though not dogma, is a clerical sacrifice, and wanting to abolish it because of clerical abuses would be “like banning cars because some people crash them.”

But on most issues, he is resolute. In 2018, after the German Church published its controversial pastoral handbook Walking with Christ – In the Footsteps of Unity: Mixed Marriages and Common Participation in the Eucharist, Cardinal Arinze insisted that the Holy Communion is a privilege for Catholics, not to be shared with Protestants. When, four years later, the drafts of the German Synodal Path leaked, suggesting the Germans would revise their catechism on women priests and gay people, he joined a coalition of cardinals, archbishops, and bishops in penning a “fraternal letter of concern.”

Months afterwards, the Belgian Church announced blessing ceremonies for same-sex couples, and he criticized it as not pastoral: “Holy Scripture presents homosexual acts as acts of grave depravity,” the Church tradition “has always declared that homosexual acts are intrinsically disordered,” and “persons with homosexual inclination are to be respected and not unjustly discriminated against,” because “they, like every Christian and indeed every human being, are called to chastity.”

When a reporter for the UK’s Catholic Herald asked him about comments, by the Guinean cardinal Robert Sarah, that the Church is in the midst of a “dark night,” Arinze referred people doubting their faith to the Catechism of the Catholic Church.

He has pushed back against suggestions that he hews close to a literal interpretation of liturgy because he is African, and, naturally, conservative, and, by implication, holding the Church back from “progress.” “That word, ‘conservative,’ is understood by people in different ways,” he said in an interview. “Suppose you say that when we did arithmetic, we learned that 2 + 2 = 4. It’s still the same, so am I then ‘conservative’ for saying so?” And, he added, African societies are “not against Christianity. In many ways, Christianity is challenged much more in Europe than in Africa.”

In the last decade, African voices are being heard more because there are now more in the Church, compared to during the Vatican II era. It is a wave that the cardinal has helped amplify. In 2015, he wrote the Foreword to Christ’s New Homeland – Africa, a collection of essays by ten African bishops, issued ahead of the Synod of Bishops on family. The positions of African bishops are not shaped by politics, he has argued. The Church opposes both divorce and polygamy, for instance, but where the Western tendency to divorce breaks up families, the African tendency to polygamy keeps families together, because Western worship is secularistic and private where African worship is communal and celebratory. Still, there is variety. “Each people will live that faith and be themselves,” he explained, which is why, in Europe itself, Italian Catholicism differs from Irish and German Catholicisms, just as, in Africa, Nigerian Catholicism differs from Tanzanian Catholicism.

In the mosaic of life, faith, for him, is not separate from everything else: it gives unity to everything else. Yet religion, as he told students at Walsh University in 2019, “is proposed, not imposed.” One must “start with meeting people where you are,” on a common ground.

“If you don’t understand a person’s religion, you haven’t even begun,” he said to Catholic Herald. “And if you are not able to listen, you are only able to talk, then you are still on your own. There are some desires of the human soul which that other person is looking for. There are, maybe, mistakes in the way that religion is looking for those things. But the human heart, created by God, is looking for Him.”

Commonality, a goal of a globalized world, is embedded in the principles of the Church, of all orthodox Christianity — the catholicity, the oneness — yet, in broad practice, the Church is often slow, often reluctant, to open its arms. As the times turn, often with alacrity, surely the Church must want to maintain relevance? Where does he see its future?

“Religion is about our link with God, our creator,” His Eminence replies. “So religion, the Church, if you like, will continue to be a necessity for the human being. There are challenges. Some people challenge religion; it can be due to human weakness, human desire for money, desire for pleasures uncontrolled. But the role of the Church remains constant and we absolutely need religion because we absolutely need God. The Church will not fall because the Church has the guarantee of Christ the founder.”

Divine assurance of longevity is no immunity from earthly scrutiny, though. For decades, scandals piled up. The Vatican Bank was suspected of laundering money for the Italian Mafia. Clergy in Spain and Chile were alleged to be part of a network of baby thefts. The Church opened investigation into sex abuse and coverups involving over 3,000 priests in Europe, Australia, and the Americas. There was internal strife, too. American nuns were in rebellion. Claims of a gay prostitution ring. Suspicion that a powerful group of clergymen was undermining the pope.

In 2012, an Italian journalist, Gianluigi Nuzzi, dropped a bombshell book, Your Holiness: The Secret Papers of Benedict XVI, based on private correspondence allegedly leaked by the pope’s own butler. The VatiLeaks changed public perception. The Church was no longer seen as the infallible guiding light: it was now another aged institution prone to corruption and infighting, driven not always by faith but by personal rewards. The pope commissioned an investigation into the leaks. In early February 2013, a 700-page dossier arrived at his desk.

Cardinal Arinze was summoned to the Apostolic Palace, the pontiff’s residence. Summoned, too, were some cardinals, bishops, and senior Church officials. The Pope informed them. He was 85, his physical and mental powers were declining, and he had decided to resign.

The news shocked the world and spun more conspiracy theories. The last pope to voluntarily give up office was Celestine V, in 1494.

A procession of cardinals was touted as potential successors, among them Marc Ouellet of Canada, Tarcisio Bertone and Archbishop Angelo Scola, both of Italy, and Oscar Rodriguez Maradiaga of Honduras. The British paper The Spectator highlighted Cardinal Arinze as, again, the bookies’ favourite, even though he, at 80, was retired and no longer a voter in the conclave. Another African was being touted, too: Peter Cardinal Turkson of Ghana, then president of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace and former Archbishop of Cape Coast.

Although the conclave is not swayed by public perception, and is, in theory, reliant on the Holy Spirit for guidance, there is undeniable politics at play given the European-heavy constitution of the College of Cardinals. Reports emerged that even as he traveled to Cameroon, Angola, and Benin and called the continent “an immense spiritual lung,” even as he was claimed to have privately touted that a Black pope would “send a splendid signal to the world,” Benedict XVI created so few new African cardinals. Of the 90 he appointed in eight years, only eight were African, a tiny 8.8 percent for a continent whose Catholic population increased 46.2 percent in the same period, from 130 million to 176 million.

To have an African pope, the majority-white College of Cardinals would have to put aside racial bias and choose someone from a majority-Black continent. An unthinkable ask. It gave weight to what Archbishop Buti Tlhagale of Johannesburg was quoted as saying before the conclave of 2005: “They don’t think we are ready for high positions. They fear paganism might come through the back door.”

(According to a supposed “secret diary” from the conclave, Cardinal Arinze did not receive up to two votes from the 115 electors — including 11 Africans — in 2005. In 2013, Cardinal Turkson received two votes, but the conclave was leaning towards the Americas, and the eventual pope had the support of most African electors. Of the 236 current cardinals, 29 are African and 17 are electors. Presently, there is no African heading a dicastery in the Roman Curia, following the resignations of Cardinals Turkson and Robert Sarah of Guinea, both recently touted as potential popes, both even more conservative than Arinze, with the latter viewed, in Catholic Herald‘s phrasing, as “part of the loyal opposition to the current pontiff.”)

(The succession has become even more fraught in the papacy of Francis, as part of a clerical pushback on his efforts to modernize the Church, amid furious theological and culture debates. While cardinals cannot comment on their voting choices, the pontiff can. This year, he stoked the furor by saying he voted for Cardinal Ratzinger in 2005 and criticized an effort to use him, an Argentinian who is ethnically Italian, to prevent the accession of a “foreign pope.”)

(Hollywood has picked interest, too. This year, a new film Conclave, from the director Edward Berger, fictionalizes a conclave in the Vatican, with all the politics. One of the characters is a Nigerian cardinal — clearly based on Cardinal Arinze — who emerges as a contender for the papacy. He is played by the Tanzanian actor Lucian Msamati.)

Still, as for his or any other candidacy from his continent, Cardinal Arinze told the BBC, “I don’t think it’s relevant where the pope comes from. The most important thing is that the pope can deliver the goods. If he doesn’t deliver the goods, what do we gain even if he comes from my own village? For me, it’s not important. What matters is that he’s a Catholic.”

When the people of Eziowelle conferred a chieftaincy title on the cardinal, they called him Ocho Udo Uwa: Peacemaker of the World. Before he left the second time for Rome, in 1984, the Onitsha laity wanted to build him a house in Eziowelle, because the mud walls of his father’s compound had become a place of pilgrimage, but he declined. He will live only where his service requires him to. At Nigerian airports, officials do not look at his passport; they just ask for his blessing. He is not unrooted in Rome. His apartment in the Vatican overlooks St. Peter’s Basilica. Before his knee surgery in 2012, he spent his evenings playing tennis, before Rosary and Vespers.

Of the 2,625 council fathers of Vatican II, he is one of only five still alive. All were born in the 1920s: Mexico’s José de Jesús Sahagun de le Parra, Bishop Emeritus of Ciudad Lazaro Cardenas, is 102; South Africa’s Daniel Alphonse Omer Verstraete, former Bishop of Klerksdorp, and South Korea’s Victorinus Youn Kong-Hi, Archbishop Emeritus of Gwangju, are 99 years old; India’s Alphonsus Mathias, Archbishop Emeritus of Bangalore, is 95. Of them, Arinze is the youngest. When he turned 90, in 2022, the Nigerian Church held a celebration and John Cardinal Onaiyekan, Archbishop of Abuja, called him “one of the very few in that hallowed category of ecclesiastical ancestors.”

Dominic Cardinal Ekandem, before his passing, had been moved to offer high praise to Arinze while he was still in Onitsha: “His voice eloquent and his pen versatile have long since been heard and read through the land. His special charism is that of moving and doing. His Grace initiates, leads and gets great things done for Christ. When Pope Paul VI of happy memory visited Uganda, he envisioned Africans becoming missionaries to Africa and the world. Archbishop Arinze is a noble personification of the high hopes of Pope Paul VI. He is an apostle in the grand tradition of the first Paul, the Apostle to the Gentiles. He is a patriot of great distinction.”

Ekandem, a cardinal-priest, died in 1995. Since Arinze, Nigeria has had three more cardinals, all cardinal-priests: Anthony Olubumni Okogie, Metropolitan Archbishop Emeritus of Lagos, created in 2003; Onaiyekan, in 2012; and Peter Ebere Okpalaeke, in 2022. (Okpalaeke’s elevation was the stunning culmination of a destabilizing turn of events. His appointment as Bishop of Ahiara Diocese in 2012 was met with unprecedented resistance by local clergy, who wanted a native of the region instead. It was a shocking challenge to papal authority, unheard of in the modern era, and Francis I demanded letters of apologies from the priests of the diocese. They apologized but insisted. Okpalaeke resigned in 2017, and, three years later, was appointed Bishop of the newly created Ekwulobia Diocese; two years on, the pope raised him. The Ahiara crisis laid bare a Nigerian Church cannibalized by regionalism.)

I’d read that His Eminence used to visit his friend, Bishop Mark Unegbu, in his retirement home in Owerri, before the bishop passed away in 2002. I returned to that personal history, how, without Bishop Unegbu’s mediation, he would not have become a priest. What might his parents feel were they here to witness how far he went?

“The first time I went home from the seminary, my father was very surprised,” the cardinal recalls. “He said, ‘So we can see you again; people told me that, if you become a priest, we will not see you again, that you are not my son anymore.’ I said, ‘It is not true. I’m on holidays now. Let’s go to farm. I will be on holidays every year.’” His Eminence has a smile on his face and an increased bounce in his voice.

“The day I was made Bishop, my father was there. He sat on the front bench in Holy Trinity Cathedral, now Basilica, and it was Bishop Nwedo of Umuahia who preached. Divine providence worked and earlier my father had become a Christian. So you can see that the ways of God are beyond us. God is providence. He knows our details, our every sitting down and standing up. Sometimes we think we are in control. Not so much.”

The Cathedral Basilica of the Most Holy Trinity, Onitsha, sits on raised land commanding a view of the Niger and of Main Market, reputed to be Africa’s largest market. The original 20 hectares was given to the Irish missionaries one month after they arrived, on January 6, 1886, by the then Obi of Onitsha, Anazonwu. The first building was finished in 1935 and consecrated a cathedral in 1960, but, during the Biafran War, it was pumelled by Federal forces. As archbishop, Arinze oversaw the reconstruction. All deceased prelates of Onitsha Archdiocese are buried there, including Bishops Shanahan and Heerey, and the two who came after Arinze, Archbishops Stephen Ezeanya and Obiefuna. The cathedral also holds the relics of the Blessed Tansi. In 2007, four years into the archbishopric of Valerian Maduka Okeke, Pope Benedict XVI elevated it to a minor basilica, the only one in Nigeria.

At Cardinal Arinze’s episcopal golden jubilee celebration, held at the basilica in 2015, there was an unlikely guest: Yakubu Gowon, the former military head of state who crushed Biafra and, afterwards, throttled the old Eastern Region; who while three million people, mostly children, died from bombs and starvation at his whim was getting married at the Cathedral Church of Christ, Lagos; Gowon whom Arinze had gone to Lagos to beg when he was about to deport the missionaries.

“The Church is still standing,” the cardinal said to the general. He’d forgiven him.

Last Christmas: the cardinal in the basilica: where he returns at the end of every year. Though newly 91, there are functions he does not miss: religious visits: to convents, seminaries, novitiates, monasteries; and social visits: to prisons, hospitals, schools. Daily, people who miss him at the functions go to the basilica offices. Is His Eminence in? they ask. Can he talk? They know that, with the drain of age, he needs his rest. On Sunday, he appears and says Mass, and delivers his annual lecture. Afterwards, people sit, wait, ask: His Eminence, tell us, what has been going on in Rome for the last 12 months?

The cardinal sits, heavy with the weight of history. The Church is less than 200 years old in Nigeria, he likes to remind them, but more than 2,000 years old in the West. One hundred years ago, it was white missionaries speaking in the same church, bringing the gospel. Now it was Africans taking the gospel to Europe and America, seeking to relight the lost fires of those continents. Now, in terms of sheer numbers, the future of the Church may be African. Now he sits here: a son of the soil named after Ani, goddess of land and most powerful deity of his people, but reconsecrated in the service of the great God, Chukwu himself. Paradoxes he ponders, but does not deem coincidental. Human causality in history, for him, is “made-up”: our ego believing in our control of events. Instead, he sees Divine providence: the Hand of God.

The cardinal smiles. He wants to speak to his people. The catechist announces: Let those in a hurry go home; the cardinal wants to speak with us! Most people remain and he talks to them, with them, in his humourous, affirming manner. They ask for his blessing again and he gives it: in the name of the Triune God, still young in our land. ♦

Update on Sept. 1, 2024: We included details of the new film Conclave, which features a character inspired by Cardinal Arinze.

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

No One Covers Culture, Literature, & Film Like Open Country Mag

— Cover Story, December 2023: How Leila Aboulela Reclaimed the Heroines of Sudan

— Cover Story, March 2023: How Rita Dominic Became Nollywood’s Most Acclaimed Actor

— Cover Story, December 2022: Chinelo Okparanta, Gentle Defier

— Cover Story, April 2022: The Next Generation of African Literature

— Cover Story, February 2022: The Methods of Damon Galgut

— Cover Story, September 2021: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is in a Different Place Now

— Cover Story, July 2021: How Teju Cole Opened a New Path in African Literature

— Cover Story, January 2021: With Novels & Images, Maaza Mengiste Is Reframing Ethiopian History

— Cover Story, December 2020: How Tsitsi Dangarembga, with Her Trilogy of Zimbabwe, Overcame

One Response