As the new home of Folio Nigeria, a subsidiary of Folio Media, Open Country Mag is republishing culture stories that first appeared on the site under its CNN affiliation. This story was first published in 2020.

When Grace Yakubu first peered into the view finder of her new camera in 2012 and captured a moment, she took her first step into an unlikely photography and filmmaking career.

“I was always fascinated by photographs and pictures in magazines,” the 41-year old tells me over the phone in March. “I was always fascinated by how things were put together to get the picture that was taken, and in the machine that got the picture. When I was around five or six, my father returned from an international travel and brought a camera. I was fascinated by how you could point a small machine like that somewhere and get the exact place captured.”

But before filmmaking and photography, she did not always know what she wanted to do, or be. She “got married at a young age and was just lost in my husband’s world,” she tells me. “It was easy to just sit back and enjoy his provision.” Yet Yakubu was one of those people who could not live through routine for a long time, and so she got a job for the first time when she was 31. It was as HR at a company. But soon she grew restless again. She was hungry for something that would set her soul in motion. That morning in 2012 that she bought her first camera, she started to devour YouTube tutorial videos on photography.

In 2015, she had the chance to go into TV production. She wanted to do a behind-the-scenes documentary on her photography. But the more she thought about it, the more she felt that it would be a waste of opportunity. “I thought, why just me? Who am I? Where did I come from?” she says. She then planned to make it about five female photographers in Lagos. But even that decision did not survive ideation. “It occurred to me, like, why Lagos?”

She was from Kaduna, in the northern region of the country, and had grown up in Kano, a nearby state. “I just started thinking about my life growing up in Kano. I don’t remember people ever talking to me about my future. It was always about marriage — I know that’s not the same for some northerners but my immediate environment was about just that.” She decided she would do a documentary about northern Nigerian women. She wanted to tell the stories of arewa women who grew up in an environment similar to hers, under conditions like hers, and yet went ahead to become successful.

“And I am careful with the word ‘successful,’” she says. “ ‘Successful’ doesn’t just mean you are popular and famous and rich. ‘Successful’ also means Maman Sani who stood by her son as he tried to recover from his drug addiction, and who, when he eventually died from the addiction, began to help other young persons get through their own addictions. ‘Successful’ is Maman Elizabeth in Bauchi who didn’t have anything, but who, when her husband died, had to stand up and take care of her children, and who went ahead to become a graduate. ‘Successful’ is the story of Aisha Augi who became a photographer early and at a time when it wasn’t cool to be a photographer as a northern woman. The story of Fati Abubakar, who is also a photographer, documenting the stories of ordinary Borno people in the midst of the Boko Haram fight.”

Three years after her decision, Yakubu created Haske Matan Arewa, a series that has featured over 60 women, one woman per episode. Each season has 13 episodes and there have been four seasons. She wanted girls in the rural north to see and know that they are capable of greatness, and so all the interviews were conducted in the Hausa language, the dominant language spoken by her target audience. Importantly, Haske aired on Arewa24, the biggest Hausa-language TV channel in Nigeria. The series has since become a household name for many northerners. “It became so popular that we had big women — governors’ wives — calling in, asking to be on it.”

Yakubu is affected and inspired by all the women she has interviewed on Haske Matan Arewa, but she’s particularly touched by the story of Kyenpian Nyabam, a young woman in Jos, who started an orphanage despite meagre resources, to care for abandoned children with HIV. Nyabam started it in 2006, at a time when stigmatization of HIV patients was the norm.

“When we did her episode, I always was in awe of her courage: the ability to know your purpose and stick to it however difficult it is is not glamorous or easy,” Yakubu says. “That episode changed me, it made me push harder at the things that I wanted to do, it made me appreciate my life better.”

Yakubu has people who influence her; she sees them as her alternate family members. Maya Angelou is the origin of this family, her “grandmother.” It is her simplicity that Yakubu wants. “I am a very complicated person, I think,” she laughs. “So I strive for that simplicity.” She’s also inspired by Oprah Winfrey, her “mother.” “I find something supernatural about her ability to ask the right questions, connect to people, get people to open up.” She is further motivated by how Ava Duvernay’s work has social justice at its core. Duvernay is her “sister.” Like her, Yakubu is keen on “challenging social biases, prejudices, and the patriarchal system.”

Yakubu is currently producing her first film, titled Aljana, which translates to “female demon.” It is a Hausa movie about how culture and religion punish children they do not understand because they do not fit into what we regard as the norm. “Stubborn children, medically challenged and autistic, artistic, creative, ‘weird’ children.”

Her desire to go into film was simply to broaden her medium of telling stories. “My passion is more in the storytelling than in the technicalities. It is about the story and how it’s told.” On set, the first thing Yakubu does is pray. “As a producer and director, you could plan every single thing beforehand and still have certain things go wrong. You can never over-plan.” And then she tries to feel the atmosphere by interacting with her crew, getting re-acquainted with the story she’s there to breathe life into. “Where is the story going? Where is it coming from?”

Haske Matan Arewa is currently on break, to return by the end of the year. Yakubu hopes for more impact. “I wanted to celebrate our women, I wanted to change minds. If a father changes his mind about not sending his daughter to school just by watching an episode of Haske, that makes my life.” ♦

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

More Stories from Folio Nigeria x OCM

— Matriarch of a Music Dynasty

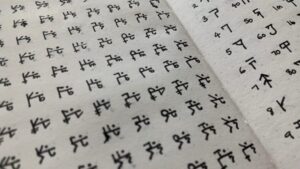

— Inventing Ndebe, an Indigenous Script for the Igbo Language

— A Tech Startup Took on the Gender Gap

— Out of a Lagos Street Boxing Academy, Big Dreams & a Child Star

— Aisha Ahmad, Princess of Polo

— How Taaooma Became a Social Media Phenomenon

— Nigeria’s New Wave of Experimental Metal Sculptors

— The Women Weavers of Akwete

— Against Sexism, Female Photographers Push Back with Skill

— A 17-Year-Old’s Hyper-realistic Portraits in Charcoal

— Intissar Bashir-Kurfi Is Collecting Nylon to Save the Environment

One Response

Very inspiring and touching🔥❤️