As the new home of Folio Nigeria, a subsidiary of Folio Media, Open Country Mag is republishing culture stories that first appeared on the site under its CNN affiliation. This story was first published in 2020.

“I had lofty goals,” Lotanna Igwe-Odunze tells me on Zoom, about the time, 12 years ago, when she decided to create an indigenous writing script, Ńdébé, for the Igbo language. It was the end of 2008 and she was 19, attending Canisius College, a private Jesuit university in Buffalo, New York, whose international student population was mostly Nigerian and Japanese.

“I was living in the dorm with a ton of Japanese people and I casually observed their culture,” she recalls. “I thought it was elegant how they wrote. I thought, ‘How come we don’t have our own writing system?’ Most Africans who write African languages do not write it in a script that originated from their culture; we use the Latin script.”

A script is an emblem of cultural memory, which is why the Latin script immerses us in Western power and the Arabic script reminds us of Islamic civilization, which is why Ethiopia, one of Africa’s two uncolonized countries, has used the Ge’ez script since 500 B.C., the only indigenous African script in use at a national level. (Of the four original writing systems — the Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Chinese, and Mesoamerican — none came from Europe.)

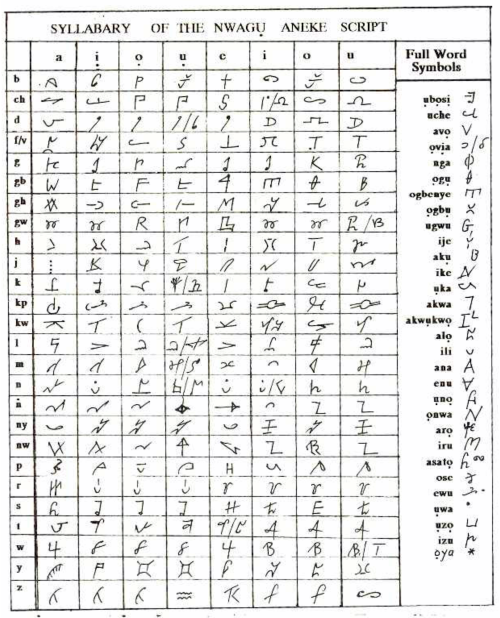

Across Africa, there is a tradition of indigenous inventors challenging the Latin script’s centrality. For the Igbo language in Nigeria, there was Nwagu Aneke, a presumed unlettered but influential landowner and diviner in Umuleri, present-day Anambra State, who, in 1960, on the eve of Independence from Britain, announced that the spirits had taught him a new writing system. His invention was a syllabary — a system in which all sounds in a language are represented as combined characters — and he wrote in it, as documented by Chukwuma Azuonye, sharing anti-colonial messages and re-asserting the superiority of African cosmologies in over 100 books.

When Nwagu Aneke died in 1991, Lotanna Igwe-Odunze was still a child, but growing up in a potpourri of languages and culture. An early reader, she spoke Igbo and English, learned Yoruba in primary school, Hausa in secondary school, and, in a bizarre twist, opted to sit for her SSCE in Spanish, which she taught herself.

At Canisius, studying business administration and living with Japanese students, she took further classes in Spanish, Buddhism, and Islamic history and jurisprudence. Her fluency in and comparison of these languages led her to recognize the problems with her native tongue: Igbo is a tonal language, but in a Latin script that isn’t made for it, that doesn’t cover all its sounds, tone-marking is difficult, creating bad spelling, mispronunciation, and preventing fluency.

Despite not being a trained linguist, Igwe-Odunze sketched a concept with built-in notation, covering the full range of Igbo phonemes, and began researching script-making. In 2009, the year a Luo script was developed in Kenya, the year history was removed from the secondary school curriculum in Nigeria, she, who hadn’t seen those coming, created a working script in one week. She blogged a post titled “The Igbo Academy and the Ńdébé Project,” explaining how her script would be a workable solution, her plan for an Igbo Academy to create and coin new words for things it lacks the vocabulary for. Then she shared the script on Nairaland.

“They laughed me out of the room,” she tells me, “and it was all Igbo people. They said, ‘This is nonsense, who is going to use it? It looks like Chinese.’” Hurt, she deleted her account. “I said, ‘You know what? I’m going to do this and not tell anybody.’ Some people thought it was novel but they didn’t really care.”

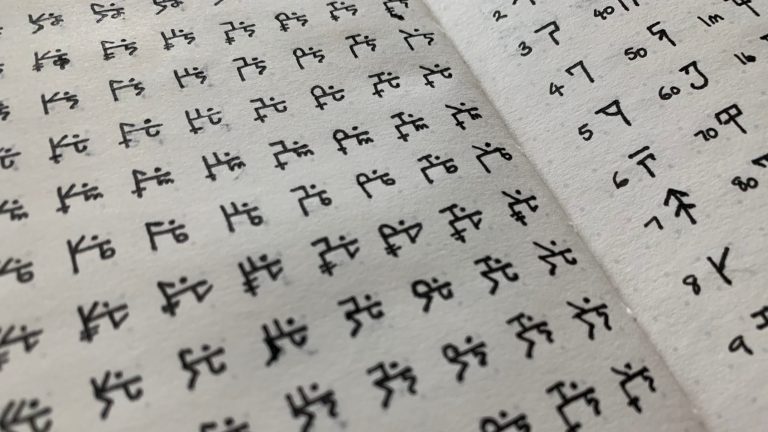

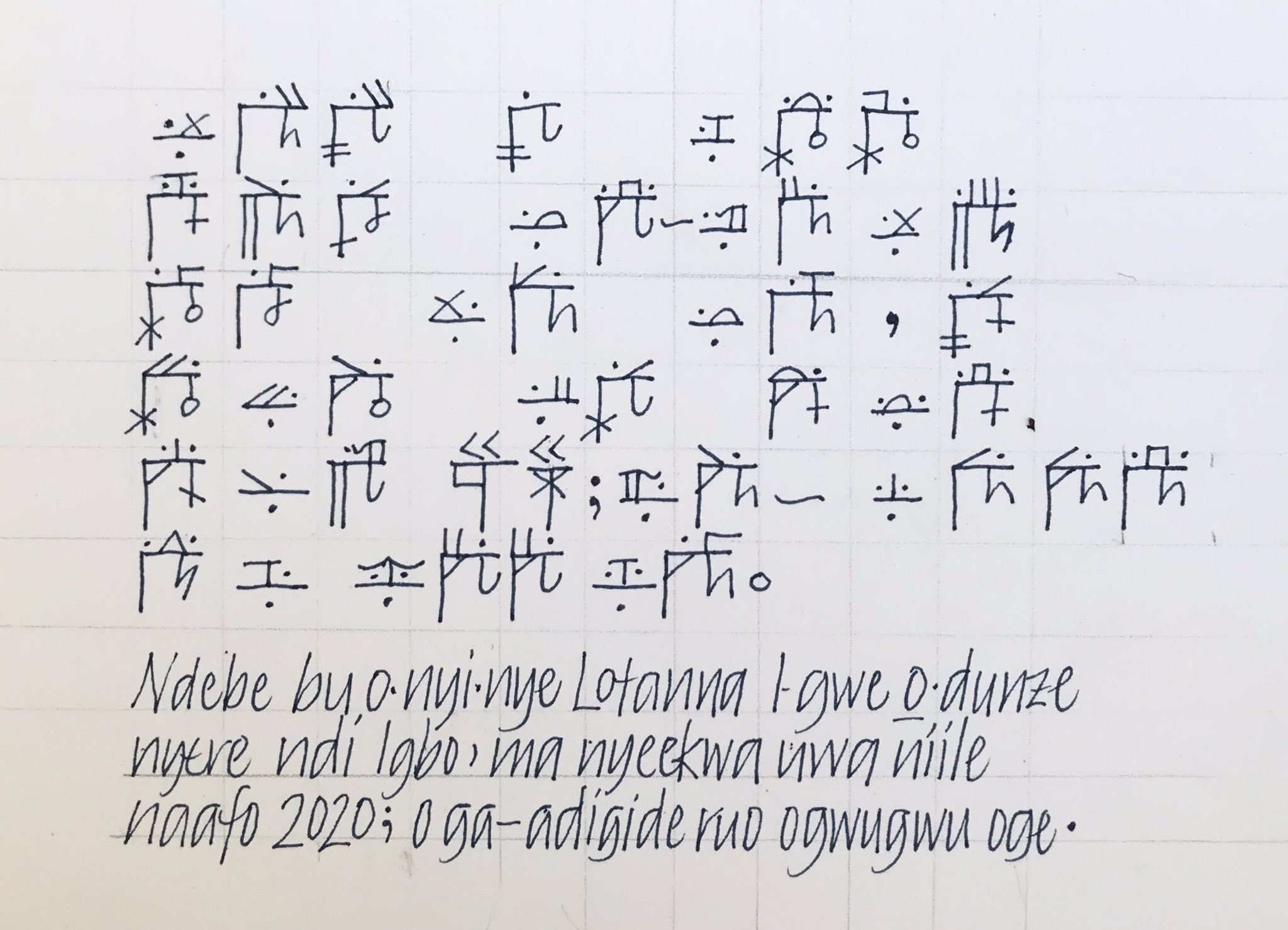

But eleven years on, when she shared the completed project early this July, codified in a book, Ńdébé: A Modern Igbo Writing System, the online reaction was the opposite. She was praised, recognized, as an inventor.

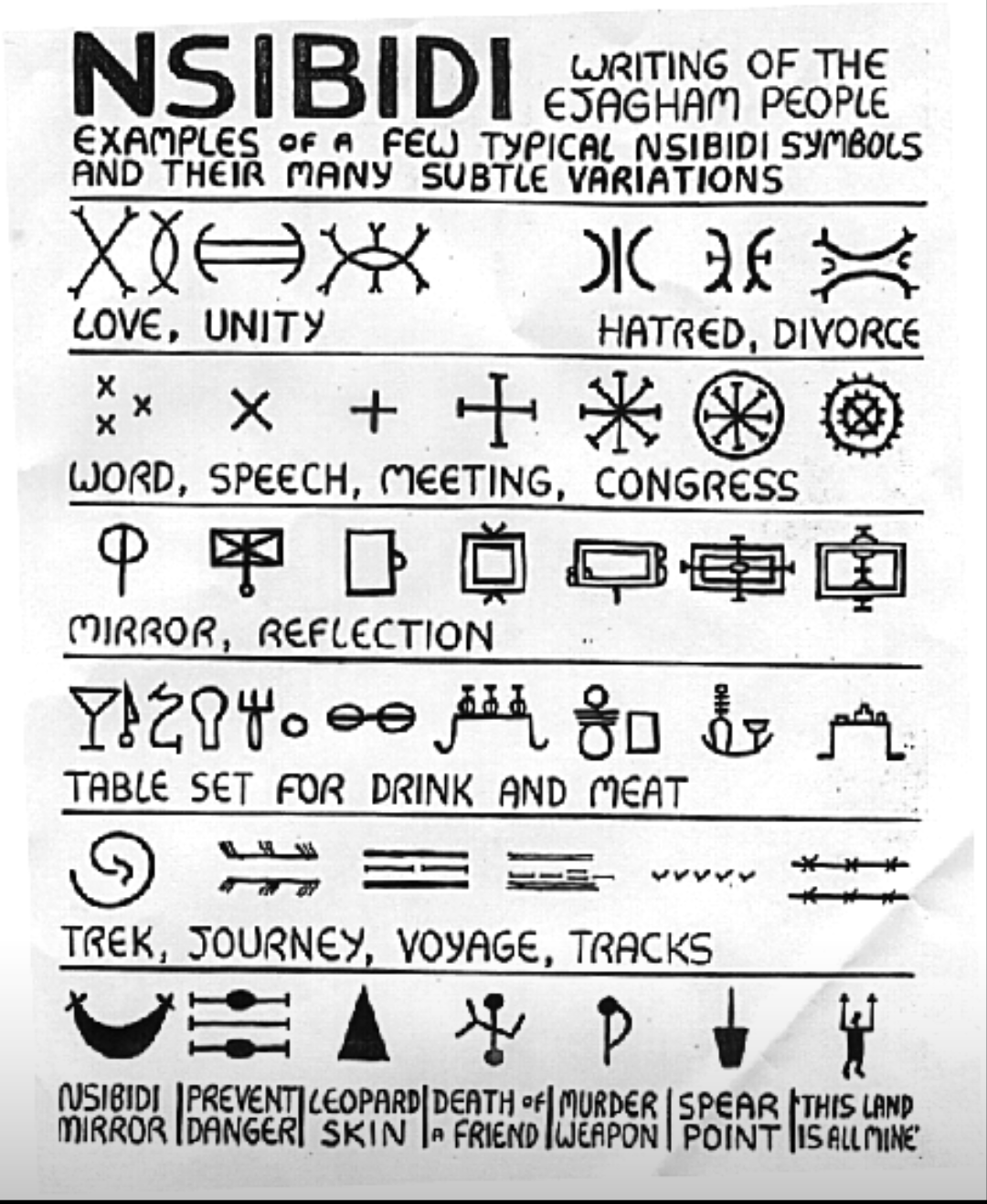

At first, Igwe-Odunze did not intend for Ńdébé to be its own full system; she intended it to supplement Nsibidi, the famed script of Ekoi origin used by the precolonial Igbo, to expand Nsibidi by creating new characters for it. But she met a dead end.

“The Japanese language is written in three systems,” she explains. “They write mainly in Kanji and make up verb endings in Hiragana and Katakana, which are syllabic and indigenous. Nsibidi, like Kanji, is pictographic and based on the Seal script, which the current Chinese script evolved from. I thought, if Nsibidi could be the stand-in for Kanji, I could create a script as stand-in for Hiragana. We would use both to write Igbo.”

However, every Nsibidi character represents a concept, which means there is no upper limit to the number of characters, which means that once there’s a new concept, then a new character was needed, which meant the project would never be finished. “I found that even the Chinese had this problem,” she says. “Many Chinese struggle with their system because it is expansive, over 50,000 characters.”

There was only one solution: she took Ńdébé apart and started again from scratch, altering its structure, its appearance, building it to function as a full writing system, one that paid homage to but would be completely separate from Nsibidi and Nwagu Aneke’s proto-script.

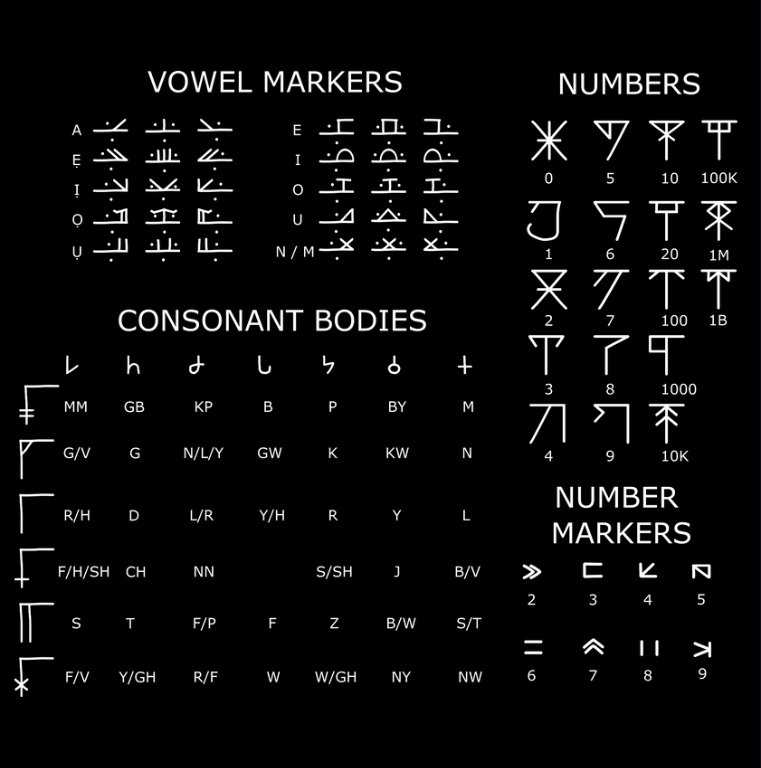

“I took the vowel system and inserted logic in it,” she details. “The vowels give visual cues about what tone it is. Then I moved it from an alphabet to a syllabary, which makes more sense for Igbo.”

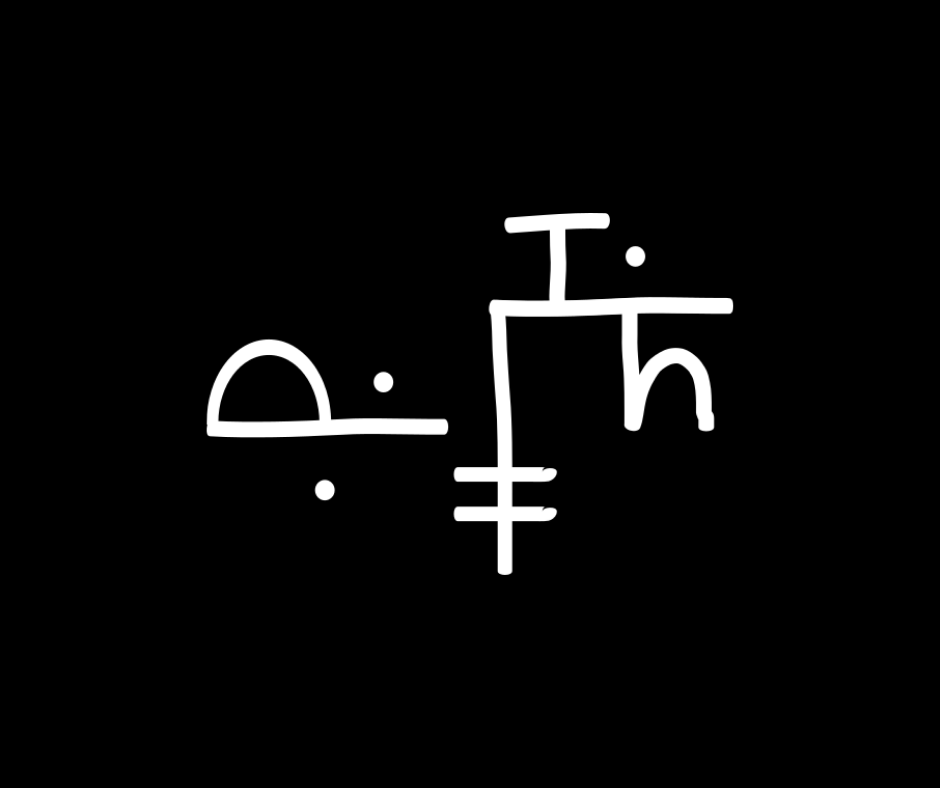

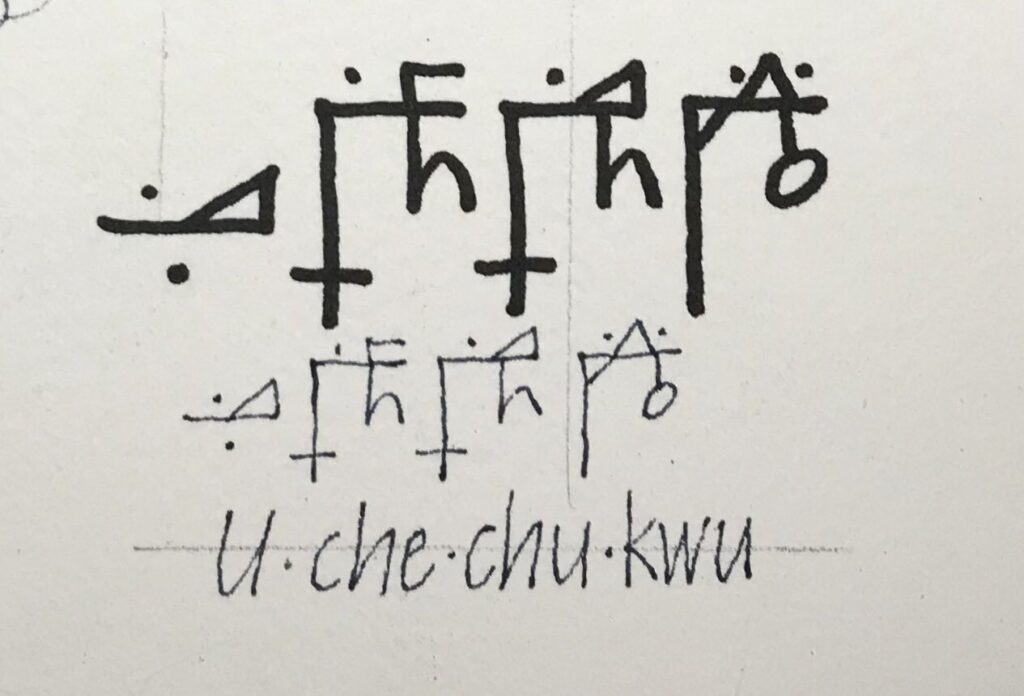

Alphabets are easier to learn than syllabaries, and by changing Ńdébé to the latter, she solved the tonal problem in Igbo but increased the complexity, and had to devise a secondary solution. “I made it a formulaic syllabary,” she clarifies. “Unlike a normal syllabary, you don’t have to memorize every syllable. You memorize the components and use logic to figure out what you’re writing. I needed it to be as easy and functional as possible.” The new Ńdébé script has 1,174 characters, but only 97 must be memorized to write Igbo completely.

When Nwagu Aneke’s proto-script became public, it was misdescribed in the Nigerian media, with its inventor’s seeming agreement, as Nsibidi. Right after Igwe-Odunze’s announcement, people also compared Ńdébé to Nsibidi. But the difference is not only in form — they look nothing alike placed side by side — but also in function. An Nsibidi drawing represents a concept — love, divorce, God—but an Ńdébé drawing represents a sound — la, da, ga.

Pointing out Nsibidi’s non-Igbo origin, she explains, “Ńdébé has an Igbo aesthetic. I studied books on Igbo artifacts and I incorporated that look. None of the characters in Ńdébé are based on Nsibidi. Every part of Ńdébé is specifically designed for Igbo.”

Within an hour of her announcement on Twitter, multiple people shared what they’d written in Ńdébé.

“The first person to write Ńdébé was a Yoruba woman,” she says, acknowledging her half surprise, as she had been thinking solely of its use for just Igbo.

The oriental inspiration came full circle when a Japanese woman sent her an email showing how she had written her name in Ńdébé.

“I would joke to my Japanese friends, ‘You people have an Igbo accent but you don’t know it,’” Igwe-Odunze says. “Chika is both an Igbo name and a Japanese name; Chi means similar things in Igbo and Japanese. The Japanese even have the R and L Factor. But phonologically, Igbo is more complex than Japanese.”

The Latin script will not be going away anytime soon, but neither will the need to save the Igbo language. In 2011, the UNESCO warned that, despite its 25 million speakers and half speakers, it might be extinct by 2050. Its pronunciations are getting lost, and with them meanings and worldviews.

In this, Igwe-Odunze feels a great responsibility. “Each new generation speaks Igbo with even more limited register and vocabulary,” she says. “With Ńdébé, we can preserve the language in an African script.” ♦

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

More Stories from Folio Nigeria x OCM

— Out of a Lagos Street Boxing Academy, Big Dreams & a Child Star

— Aisha Ahmad, Princess of Polo

— How Taaooma Became a Social Media Phenomenon

— Nigeria’s New Wave of Experimental Metal Sculptors

— The Women Weavers of Akwete

— Against Sexism, Female Photographers Push Back with Skill

— A 17-Year-Old’s Hyper-realistic Portraits in Charcoal

— Intissar Bashir-Kurfi Is Collecting Nylon to Save the Environment