As the new home of Folio Nigeria, a subsidiary of Folio Media, Open Country Mag is republishing culture stories that first appeared on the site under its CNN affiliation. This story was first published in 2020.

No one remembers why Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti loved Bob Marley, but in the late 1960s and early ‘70s, after she won the International Lenin Peace Prize for her feminist activism, she sometimes asked her granddaughter, Yeni Kuti, to write down the lyrics of “No Woman, No Cry,” and she would hold the paper and sing out loud.

Yeni was the eldest daughter of the son said to be her favourite, Fela Anikulapo Kuti, a musical genius who at the time was still perfecting the blend of highlife, jazz, funk, salsa, calypso, Yoruba music, and disruptive advocacy that he called Afrobeat and that would make him a global icon. But while Fela’s brothers, Beko and Olikoye, had become notable medical doctors, and his cousin Wole Soyinka had already published a string of plays that would put him on the path to becoming the first Black and African winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, Fela, sent to Trinity College to study medicine but gone rogue into music, was still having trouble with his wife.

Fela’s wife Remilekun Taylor — with a Nigerian father and a half English, quarter African American, quarter Native American mother — would not put up with the women in Fela’s life and had moved out of the house again. So Funmilayo left Abeokuta, with snacks of kuli-kuli for her grandchildren, and visited her son in Lagos to make peace. In the mornings, she implored Remilekun to return. In the afternoons, she boiled hot water to chase away the women coming near Fela. And in the evenings, she sat with her granddaughter Yeni, singing Bob Marley.

That was over four decades ago, and Yeni Kuti, now 61, can only remember vague details. “She took us to live in Abeokuta at some point,” Yeni tells me on the phone. “She told my parents that she was taking us for the weekend but she reenrolled us in school there. We were crying, we wanted to come home, but she was not having any of that, so we stayed there for three months. She was strict, we were scared of her slightly, we were not really close, but we loved her.”

It is a big, storied family. Yeni’s grandfather, Israel Oludotun Ransome-Kuti, was an educationist, pastor, and pianist, and her great-grandfather, Josiah Ransome-Kuti, was an Anglican clergyman and composer of Yoruba hymns. She had been born, in 1961, into the music, and soon she was being swept, like many members of the family, into her father’s outsize life. “Fela had this dancer called File. She was a big inspiration to me. I used to just sit and watch her. I asked her to teach my sister and I. It was all I wanted.” But so is her range that when Fela couldn’t afford to send her to a dance school, she took to fashion. It was the late ‘70s and she would sit in front of her father’s house, Kalakuta Republic, on Agege Road, Mushin, facing the Afrika Shrine, where her father performed, and weave designs.

Yeni was 16 and in secondary school when, in 1977, her father released the song “Zombie,” a 12-minute mockery of the military (“Zombie no go think, unless you tell ’em to think”), then led by his former primary school classmate Olusegun Obasanjo, and days later, a thousand soldiers descended on their home, burnt it, and destroyed his studio and master tapes. Then they threw her 76-year-old grandmother Funmilayo from a second-floor window.

It was the afternoon of 18 February, a Friday, and Yeni was home from school, asleep. Her brother, Femi, however, always spent his evenings at the Shrine, playing with their younger sister, Sola. But when they got to the Shrine that evening, they saw soldiers everywhere. “So they came home to alert my mum,” Yeni remembers. “We were used to the police raiding our house, we were used to him detained in the police station, but this case of soldiers was alarming.”

They went to their aunt’s house, and her aunt’s husband got ready to drive them to see, but the notorious Lagos gridlock was at work, so they decided to wait before leaving. “Sola was playing outside and two boys asked her why she was playing when her father’s house was on fire,” Yeni recalls. “My mother didn’t believe them. When we reached the Shrine, it was burnt down. It was then that my mother began to scream.”

For three days, the Kutis searched everywhere and found nobody. Then they found Funmilayo at the Military Hospital, Yaba. “I can’t even remember where Fela was. I think he was in a military hospital on Awolowo Road. Others were scattered in different military hospitals. Till today, we don’t know the number of people who died; all we know is that there were some people who used to work there that we never saw again, so we assumed that they’d died. The government never came out with information. My father was lucky; they didn’t catch him till about 10 p.m. when he was drunk. They had prior caught some people that they thought were him. It was terrible.”

The years after 1977, including Funmilayo’s death from her injuries a year later, saw Yeni and her family make pointed choices. She continued her design work and graduated from the Nigerian Institute of Journalism, a path she says was not influenced by her family’s history of activism, and, in 1988, she revived her dancing dream and joined her brother Femi’s band, Positive Force. It was not until the late ‘90s that her collaboration with Femi took the turn of consolidating their family’s musical legacy.

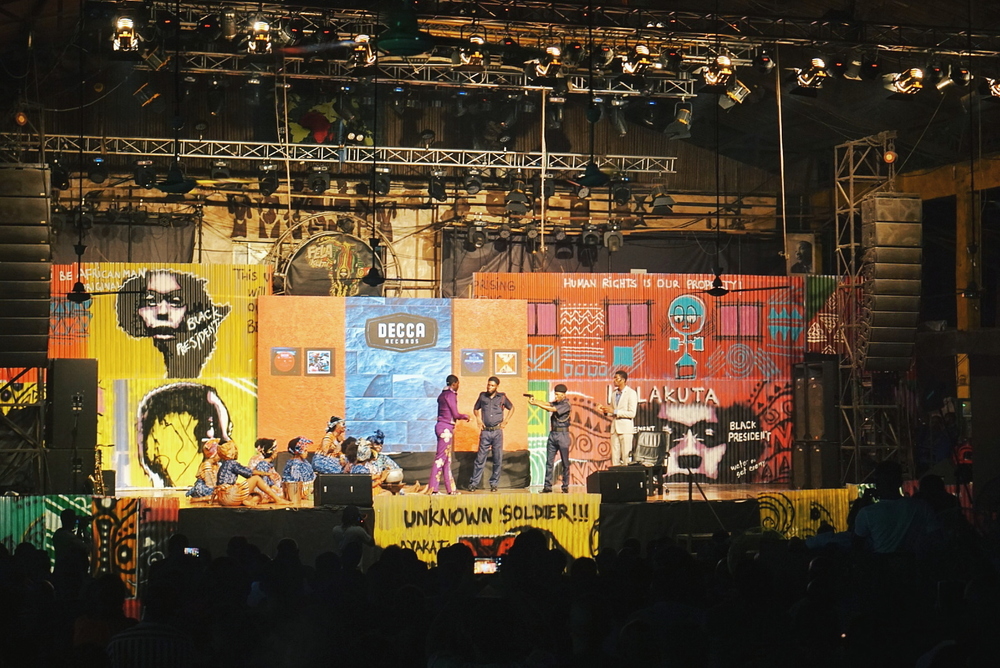

The spur was Fela’s death on 2 August 1997, and his funeral, attended by a reported one million people at the site of the burnt Kalakuta Republic. A year on, Yeni came up with the idea for Felabration, a music festival commemorating their father, held at Tafawa Balewa Square, where he had lain in state. On 15 October 2000, which would have been Fela’s 62nd birthday, Yeni and Femi opened the New Afrika Shrine, a performing arts theatre, to host subsequent editions of Felabration.

Although, at this time, Nigeria had transitioned from military to civilian rule, the president was Obasanjo, under whom the old Shrine was burnt and their grandmother died, and against whom the family was pressing the Oputa Panel — the national commission set up by Obasanjo himself to investigate human rights violations under the military — to look into. “We weren’t concerned,” Yeni says on their anticipation of government sabotage then, “we were just ready, nothing was going to stop us. We knew they’d try but there was a legacy that nothing could make us deviate from.”

It was in the New Afrika Shrine that Yeni’s daughter Polaris had her engagement, and Yeni says that whenever Femi’s son Madi married, it would also be there. “More emotional for me is the legacy of his music from generation to generation,” she says. “Most times when I see [Madi] on stage, tears come to my eyes. He plays the saxophone, there is no instrument he cannot play excellently, and he ensured he attended Fela’s alma matter, Trinity College.”

The New Afrika Shrine is an international attraction, drawing musicologists and tourists; one of its diplomat visitors in 2002 returned in 2018 as the French president Emmanuel Macron, the first time a president was visiting. Every Felabration week — which now includes a symposium, a debate series, a dance contest, and art exhibitions and competitions — the popstar sons Femi, 58, and Seun, 38, have performed alongside local and international acts. But in the world of Nigerian music — led now by Afrobeats, a multi-genre vibe named from Fela’s own Afrobeat — where status rests more on hype and style than on substance, a few superstars have placed themselves, through association or symbolism but avoiding his combative activism, as successors to Fela’s throne.

“I would like to plead the fifth,” Yeni laughs. “All I can say is, history will be the judge of if that title is valid. Fela has expressly built his own legacy in Black music, an original. It is because of how significant he is that people would always want to be ‘the new Fela.’ You can never run away from that. My brother does not want to be Fela, he says he is his own person. My advice is for people to leave Fela’s legacy and build their own.”

Fela, Yeni continues, “just defies explanations. He never let us call him father or daddy. There were some things he did in my presence that I cannot fathom till today. One time, he asked that we follow him to the barracks. I dilly-dallied till he left with just Femi. They beat them up at the barracks. Fela knew beating awaited them yet he took his son there. When I write a book, I will include these memories.”

Yeni values life’s lessons, and hers are what she brings to Your View, the all-female, multi-generational talk show she has co-hosted since 2013, styled after the American daytime show The View. On Your View, she talks about being a culturally conscious African woman, echoing her father who chose the name Anikulapo over the family name Ransome, which he called a “slave name.”

“If I see women too bent on mimicking oyibo people all the time, it would be unlike me not to try and address them,” she says. “Don’t make yourself a caricature of White people — that way you lower standards for younger women. Look at Chimamanda [Ngozi Adichie], proud in her own skin, natural hair 90 percent of the time, and she looks beautiful. I am not talking about whether you wear African attires; it is your aura — the intention behind what you put on.”

Earlier this year, Bolanle Austen-Peters’ musical Fela’s Republic and the Kalakuta Queens premiered, focusing on the 27 women Fela married in 1978 and eventually divorced. How does Yeni, who caused a bit of chatter herself by revealing that she would marry at 75, deal with Fela’s contentious legacy with women — held up in the song “Lady”?

“Let me put it this way: We, women, we were very important to Fela,” she says. “He was surrounded by women. They played much more important roles in his life than he realizes. I would not say he was anti-feminist, I would just say he had some ideas that do not conform to what feminism is about.”

As Nigeria sinks lower and lower, Fela’s prophetic star burns brighter and brighter, but even as his greatness is celebrated, and his sons Femi and Seun are feted on the world stage, his family’s pains are glossed over. From a grandmother who fought for her and other women’s rights to a mother who refused to be wronged over and over, Yeni has embraced her placement in a lineage of women putting the world around them together. With Felabration and the New Afrika Shrine, she keeps the legacy alive. On the phone, she sounds fulfilled. “I am glad we made them a monument of relevance,” she says. ♦

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

More Stories from Folio Nigeria x OCM

— Telling the Stories of Arewa Women

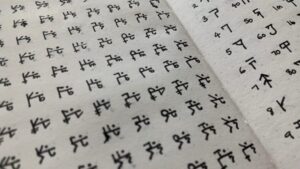

— Inventing Ndebe, an Indigenous Script for the Igbo Language

— A Tech Startup Took on the Gender Gap

— Out of a Lagos Street Boxing Academy, Big Dreams & a Child Star

— Aisha Ahmad, Princess of Polo

— How Taaooma Became a Social Media Phenomenon

— Nigeria’s New Wave of Experimental Metal Sculptors

— The Women Weavers of Akwete

— Against Sexism, Female Photographers Push Back with Skill

— A 17-Year-Old’s Hyper-realistic Portraits in Charcoal

— Intissar Bashir-Kurfi Is Collecting Nylon to Save the Environment