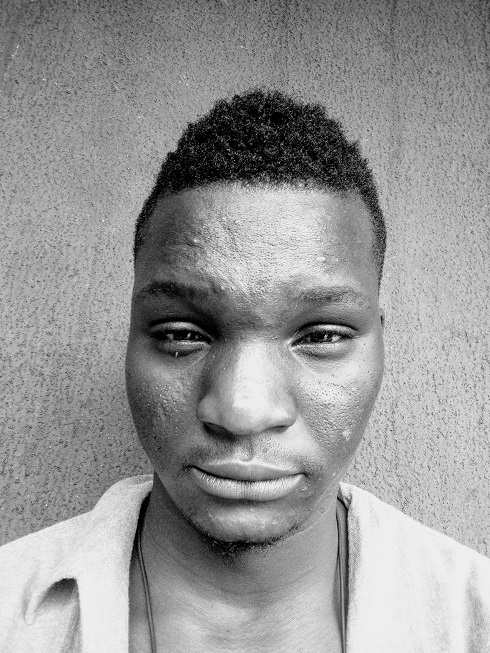

Lanaire Aderemi’s mother used to tell her and her sister stories each night before they slept, and Lanaire would wake up thinking about them. One night, her grandmother told them about the Egba Women’s Protest. It was an anti-colonialist and feminist movement against British taxation. From 1947 to 1949, the women presented a fierce and tactical opposition with their organization, their centring of collectivity and socialist strategies. They were influenced by the Aba Women’s Protest of 1929.

“I was inspired by how they drew from repertoires of knowledge that existed before them,” Lanaire writes me via email. But she was also shocked that a movement of thousands of Nigerian women was relatively unknown by young Nigerians.

“There is something so violent about Nigerians’ consciousness being conditioned to erase women’s contributions to collective liberation,” she says. “There is a violence that erasure brings, and I think that violence reproduces pain, whether it’s emotional, physical. I think what draws me first is the bodily reaction I have with erasure.”

In her debut show in 2019, an evening with verse writer, Lanaire celebrated these women. Through riveting stage scenes, she captured the force of their movements.

“I acted a lot in school but in this play, I wasn’t really acting,” she says. “I was retelling an audience my creative journey through performance, but it didn’t feel as exaggerated as a performance. It felt like I was talking to a friend.”

That year, aged 20, she was nominated for the first The Future Awards Africa Prize for Literature.

Lanaire’s multidisciplinary interests—poetry, drama, performance—come together in her art. “How the three intersect is the playfulness of it all,” she says. “With poetry, I play with sound. With plays, I play with drama. And as a performer, I play with the audience.”

Her new show, Story Story, is a three-day digital festival with workshops, commissions, and films. “Its aim is to equip storytellers with the tools needed to share their stories in the world,” she says. The show would “offer care and grace to artists who often feel very lonely in their journey.”

On the last day of Story Story, she will premiere her debut film.

As a child, Lanaire Aderemi saw Bolanle Austen-Peter’s play Saro, which gave her a love for poetry, music, and theatre. In 2015, she left Nigeria to start her A Levels in the UK. Encouraged by her mother to compile a book from her journals and WordPress entries, she published her debut anthology, of ivory and ink, in 2017.

Months after getting her degree in sociology from the University of Warwick, Lanaire wrote a play, and seeing over 300 people in a lecture theatre was all she’d ever wanted. The play got her residency at the Birmingham Rep Theatre, where she learned more about dramaturgy, directing, and writing.

Reading Oyeronke Oyewunmi’s What Gender is Motherhood? reconceptualized Lanaire’s understanding of mothering. Aside her biological mother, she saw anew the other mothers who nurtured her craft —secondary school teachers, boarding school mistresses and cooks.

“I was surrounded by a community,” she tells me. “I believe that communal care is necessary for collective liberation.”

For Story Story, Lanaire applied to Arts Council England for funding. She wanted a number of Black creatives to be commissioned and paid a token. A collaboration with the creative agency motherSun will also support the artists through lateral networking and funding. They received 31 applications and selected five. The commissions, known as “Call and Response,” will be showcased during the festival to celebrate artists’ creative journeys.

“I know so many talented people who find it hard to navigate the creative industry and I wanted to create an event that addressed that,” she says. Story Story is “partly inspired by my childhood experience of feeling seen as a young writer.”

Co-facilitators of the virtual festival include the playwrights Inua Ellams and Chinoyerem Odimba, the poet Wana Udobang, and the curator and writer Aliyah Hasinah, alongside designers, musicians, and dancers. A visual-audio set by DJ Camron will celebrate the Black history of storytelling.

Lanaire’s “call and response” approach will be central to the show. “‘Call and response’ is everywhere and I only noticed that in university,” she says. “In Nigeria, we see it in parties when the MC asks the children a rhetorical question and still anticipates a response. Maybe there is something about our culture that celebrates a co-creation of knowledge.”

She wants her shows to “feel like a home, so I frequently break the fourth wall—that is, if I ever even see a wall.”

Lanaire Aderemi places her work in the context of community. Her friends funded her play you did not break us, cooking food for the actors, providing props, offering to create a playlist. “I think we can adopt mutual aid frameworks which emphasise collective care and disentanglement from institutionality and individuality,” she suggests.

“I have seen a lot of skill-sharing and encouragement from Nigerians on Twitter,” she continues, “so I think we need more of that as well as funding. But we must [also] think of accessibility and whether we are reproducing gate-keeping.”

Today, Black artists are united in a struggle for competent structures to utilize their talent. Whether it’s the typical Nigerian shoddiness towards creatives or the racial bias in diasporic communities, there’s need for practical actions.

“It’s so important because exposure really doesn’t pay the bills,” Lanaire concurs. “If the artist is hungry, then their work is compromised already. Years ago, I might have asked for us to make demands to the state, but I don’t think we should wait for the state to recognize and value artists’ labour.”

With Story Story, Lanaire is thinking of the elevation of black art forms, inspired by state-funded events like FESTAC ’77.

“There is so much we can learn from each other across historical time and geographical space,” she notes. “So much work that should be archived and supported.”

As a writer whose work draws from sociology and history, Lanaire Aderemi regularly goes to Asiri, a magazine of archives.

“When I listen to images or read texts about historical events, I sometimes pause and think about the violence of erasure,” she says. “Is it not violent that we cannot dance in the archive we create or inherit?” ♦

Edited by Otosirieze Obi-Young.

More Essential, In-depth Stories in African Literature

— How Tsitsi Dangarembga, with Her Trilogy of Zimbabwe, Overcame

— With Novels & Images, Maaza Mengiste Is Reframing Ethiopian History

— Nigerian Literature Needed Editors. Two Women Stepped in To Groom Them

— Hannah Chukwu’s Call to Help Uplift Unheard Voices

8 Responses