On a winter afternoon in Dey House, home of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Lan Samantha Chang said hello and I said hello and I turned again, “Sam?”

“Yeah,” she said. “The mask does that. You don’t recognize people any longer.”

Mask or not, I was a bit embarrassed to not immediately recognize the director of the program, with whom I’d spoken twice while in Nigeria, on phone and on video. She is, of course, the first woman and the first Asian American and non-white person to hold the post, which she has done for the last 17 years. The Workshop itself has existed for 86 years now, since 1936, and is the first creative writing program in the U.S. and the top-ranked one for decades.

Chang, the Elizabeth M. Stanley Professor of the Arts at the University of Iowa, first came to the Workshop in 1991, for her own MFA, after her BA at Yale and her MPA at Harvard. She is the author of the story collection Hunger (1998), a finalist for The Los Angeles Times’ Art Seidenbaum Award and for the California Book Awards, and the novels Inheritance (2004), a PEN Open Book Award winner, and All Is Lost, Nothing Is Forgotten (2010).

Her work, translated into nine languages, has twice appeared in The Best American Short Stories, and has received fellowships from Yaddo, MacDowell, Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the American Academy in Rome. She has been a Stegner Fellow at Stanford, a Hodder Fellow at Princeton, and a Radcliffe Fellow at Harvard.

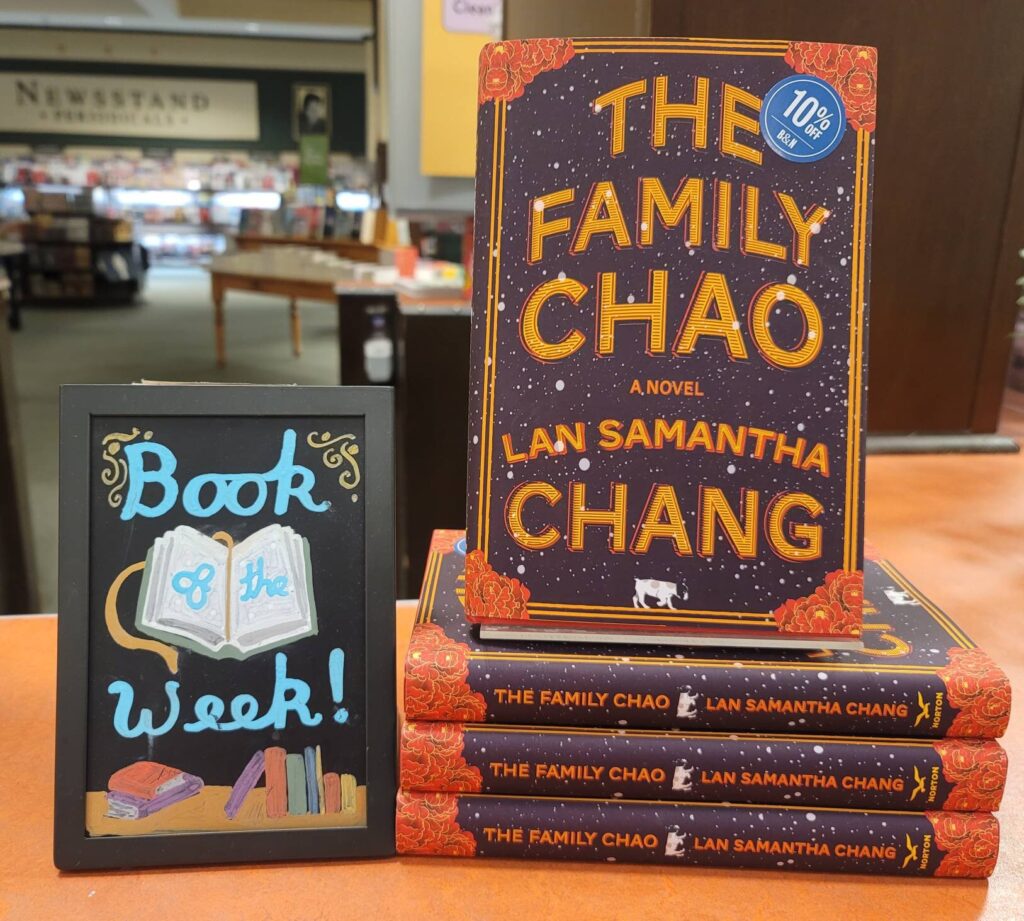

When I first met her in person, she had just returned from Germany, from the Berlin Prize Fellowship with the American Academy, and was preparing for the release of her fourth book, The Family Chao, which arrived in February, with a blurb from Yiyun Li calling it “one of the finest and most ambitious novels about America I’ve read in recent years.”

The reviews have been enthusiastic. “One of the many pleasures of The Family Chao is the way the novel dramatises the gap between how a family wants to be seen, and its messier inner realities,” Jonathan Lee wrote in The Guardian. “Chang has created a wonderful comedy of American consumption.” In NPR: “a riveting character-driven novel that delves beautifully into human psychology.” In The Star Tribune: “A playful literary romp with a serious heart. . . Operatic and subversive.” In Publishers Weekly: “Ingenious and cunning. . . For Chang, this marks a triumphant return.”

In an hour-long conversation in her office in mid-May, Professor Chang discussed, among other things, literary genres, her own writing life, and portraying an atypical immigrant community in The Family Chao.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Congratulations on The Family Chao. You said, in The Washington Post, that your previous books “fit the acceptable stereotype of the quietly suffering Chinese American family,” even though you “actually grew up in a noisy Chinese American family.” And that this was so because you were “so inexperienced, I didn’t understand that I was trying to write according to a set of rules that were standard at the time, rules that required the use of as few words as possible.” So The Family Chao is your first time writing in a “candid” way. And you think of it as “narrating a community.” The book’s two sections are titled “They See Themselves”—leading up to the death of the family’s tyrannical father Leo—and “The World Sees Them”—following the trial of one of the three sons for the murder. The Chao family eventually comes to wonder if they were ever accepted in the community. How, in your fiction, do you approach the tension between how immigrants contend with the consequences of community and how they strive to maintain their individuality?

I chose to write about a family that doesn’t fit comfortably into the community of Asian Americans in which they belong. The first reason they don’t fit comfortably is that Leo Chao, the patriarch of the family, has an outsized personality and is not a conventional person. He doesn’t behave respectably, he’s a crude man, his ambitions are outsized to the point where he doesn’t always consider other people.

There’s a scene early in the novel where he embarrasses not only his son at the Post Office but another Asian man who’s standing in line waiting, and this man is so horrified that he pretends he doesn’t know Leo Chao. I wanted Leo to be that kind of person, because I wanted to create a work in which there was more than one kind of Asian character, more than one kind of immigrant. I feel that in many ways there’s a tendency for American audiences to respond to stories of hardworking, sincere, somewhat victimized immigrants, and my characters, the members of the Chao family, are a bit too individual to fit into that mold.

So the consequences of Leo Chao’s behavior is that when he is dead, nobody really mourns him. There’s a great deal of love for his wife, Winnie, the long-suffering Winnie, but Leo himself, you know, does not get a funeral in the novel. It’s not a major community event.

It’s almost as if their reaction to the murder is a cop-out from actually confronting the absence of this person, which would happen in “grief.”

Right. I would say that people’s feelings about him are so complex that they focus instead on wondering who killed him. He is the centerpiece of the book, he’s the first character who came to my mind when I was starting the project, and I think that his influence upon his sons and in their community linger long after he’s gone.

You said you based him on your father, aside from his morality or lack thereof.

Yeah, my father was not immoral in the same way as Leo, and Leo is much better at dealing with money than my father was. Leo’s rich. He hoards money like a western dragon. My dad had a very strong personality as well; he was not a quiet person; he was a very loud and articulate and forceful person who could express himself quite well in two languages, even though he wasn’t immersed in English until he came to this country at a relatively late age. He had four daughters, and I think he felt responsible for making sure that all of us grew up with good educations but also that we grew up intact. He wanted to protect us. We were the only Asian girls of our age in town, and so he was very controlling. Of course, that didn’t really work. My sisters are very strong-willed, all of us are very strong-willed. So yeah, I don’t think our family is a typical immigrant family that is portrayed in literature.

And that you have been portraying in your previous books. What led to it?

I was following the kind of writing I had been taught, in which it is very hard to have a scene where there’s a lot of screaming. I mean, I was taught that a lot of dialogue, having characters speak a lot, is bad—I was not taught that here in Iowa but [it was] when I went to Stanford. One of my professors there said, for every one line of dialogue, there should be 10 lines of narrative or description. Dialogue should be used sparingly.

And that is just one method of writing.

Sure, but when you’re a young person, you might feel like you don’t know how to write—I mean, I was discovering writing, I suppose, for myself. But also, as a child who grew up in a family that had a lot of Mandarin spoken in it, I was discovering English, the varieties of English expression.

You have said that what interested you in The Family Chao was not plot but “the sense of time unfolding” and how it “gives the reader space to assume things and to not know what’s going to happen.” The book is as literary as it is mystery, and that ramps up tension. What is the most interesting thing that students can learn about exploring a concept across genres?

I was thinking about that. What is the most interesting thing? I don’t know what the most interesting thing is.

Give us as many as possible then?

Well, I can talk about The Brothers Karamazov. Dostoevsky was exploring the concept of the trial and the concept of the police investigation for the first time in Russian literature. His novel is really a prototype for the genre that is now the police investigation and also the crime and court case novel—there’s now a clear cut shape to that kind of narrative, which we see on TV all the time. When I wrote my novel, I left out the police investigation because I realized that everyone had seen that on TV. Dostoevsky, however, spent hundreds of pages describing the investigation. He was also a pioneer in the crime genre with Crime and Punishment.

I think genres have a way of concentrating a concept. For example, if you’re writing about time and you’re interested in time and philosophy, it becomes fascinating to look at the genre of time travel and to see how it can express your ideas.

Detective novels and time travel novels are related in a fascinating way. In most mystery novels, the narratives replay crucial moments over and over with suspects or witnesses. As a reader, you’re constantly traveling back to the time around the crime. In revising the reader’s opinion of what happened, or might have happened—revising the idea about what did happen—each time the story travels back, I am reminded of the time travel narrative in which characters go back in time to change something, to make the outcome different.

I do think that any question that interests a writer can be concentrated or explored conceptually by switching genre. But our genres have become specialized—so specialized that when you move across the line, you instantly create a new subject. Have you tried it?

(Chuckles) Um, no, I’m merely a literary fiction person.

Well, this is so interesting, right? Like, why did we come up with the idea of “literary fiction”?

Yeah, and these other ones are “genre”—they’re “crime,” they’re “mystery,” they’re “murder.”

I think it’s all about the marketplace. I mean, I look at Dostoevsky and he didn’t know he was creating a market for a specific kind of fiction with The Brothers Karamazov. In a way, I think it’s interesting to go back and mess up those lines again.

The second-year students just graduated, and you hosted a party in their honour at your home. It’s the 17th graduation you have overseen. You have talked about being inspired by your students at the Workshop over the years, how they have shown you that there can be freedom within writing rules. What goes through your mind when you see yet another set of students graduate?

Graduation always makes me sad, because if you live here in Iowa City, these wonderful, smart, interesting people come through and stay for two or three years, and then leave. That’s just the rhythm of being here. It’s very rare that you get to know a person over time, and there are so many people that I really like—it’s a little sad. But mostly, what I like about working with students, and what I think people don’t talk about—what teachers don’t talk about when they describe how teaching is bad for your writing—is that being around really inspired people who are coming to writing, not always for the first time, but perhaps really focusing on writing for the first time, is inspiring for the teacher as well.

For me, being around people who are sort of solving problems anew, their own narrative problems, is exciting, because I come into the sense that everything is new. I want to feel that way when I’m writing as well. This has really influenced this new novel in particular, it’s really changed this book.

You told the Daily Iowan that before becoming director, you “had seen the workshop from many angles as a student and as a faculty member,” and when you became director, you were “given permission to think about taking the program in a direction that would include writers from many backgrounds to make it possible for their stories to be told.” Ayana Mathis recently talked about how there were only three Black women in her fiction cohort in 2009, and how unprecedented that in itself was. Today, there’s almost everybody: Black, white, Asian, Latino. There have been several Africans lately. Currently in the program, across all the years, Nigerians alone are up to nine. But the diversity is not only on a racial level. Writers outside “literary fiction”—fantasy and speculative fiction writers—are being admitted as well. Stylistically, it’s a broad group. What does the Workshop look out for when considering applications? Has anything changed over the years?

Well, stylistically, it is a broad group. And why did I think it was important to bring so many different kinds of writers to this program? I believe that if this program is going to express and represent and champion literature, it should champion more than one kind. I feel like the writers became very homogeneous at one point, in the fiction program, during the ‘80s and early ‘90s, and so it seemed very important to be open to good fiction of all kinds, from all places.

Were you the only Asian or Asian American in your cohort?

In my class? Yes. I was one of two people of color in fiction. There was one African American woman in my class. The year after me, Alexander Chee was in the fiction class. I’m not sure how this happened, but we have at the university here the International Writing Program, which has always brought people from all over the world as its mission, and then the Workshop, which did not seem to do that as often, I’m not sure why. It just seemed odd to me.

One thing that seemed really clear to me was that if we were to represent American literature then we had to bring in literature from all over the world. There is the possibility of creating the conversation not just in this country but around the world that brings in as many voices as possible, and that is a goal of mine with this program. And that conversation has to be recreated anew each time we let in a class, and because we don’t have “slots,” we don’t have “quotas,” we’re pretty much at the mercy of who applies to the program, if that makes sense.

Yeah, it does, with the number of Nigerians currently here. I mean, if anything is open internationally, you can trust that Nigerians are applying in droves.

(Chuckles) Why is that?

Because there are over 200 million of us, we dominate the literary scene in Africa, almost everything; there are more Nigerian writers than there are probably people from some towns.

(Laughs) Definitely from some towns in Iowa.

And we’re a people who are energetic, we want the best for ourselves, so we’re constantly applying, trying to get into places, partly because the home system itself is broken, politically, but also in terms of literature, where writers are on government payrolls and hunting fellow writers, so Nigerians are looking outward, they are trying to find a way to just be better, so that’s partly why you’d find us, the writers, everywhere in MFA programs.

And everybody knows everybody else.

Yeah, most of the people know most of the people from the continent. Speaking of which, there is a notable line of African graduates from the Workshop, from Chinelo Okparanta and Yaa Gyasi to Arinze Ifeakandu, Romeo Oriogun, Nana Nkweti, and Okwiri Oduor, to name a few. I read that you advised Gyasi while she wrote Homegoing. What is your reaction to the remarkable work that these writers have published?

I mean, it’s wonderful. The thing that’s interesting about the work of these writers that you’ve listed here is that it’s so different; like if you were to compare the work that Arinze is doing, for example, to the work that Yaa is doing or Okwiri. Or Nana, who has an extraordinary diversity of aesthetics. I noticed it when she was here.

Agreed. That’s why I listed them as examples—they are obviously not the only ones but they are very different.

Yeah, they are very different and they’re all kind of amazing. Actually, there’s some people whose work is coming up. Magogodi [Makhene]’s work is really different from any of these peoples’, and so is Derek [Nnuro]’s. He has Ghanaian roots, like Yaa, but his work is very different from Yaa’s. The literary community in Africa is so rich with people who write so differently that we see it reflected here in the people who come to our program.

Also, I’m fascinated that people have inspiration from a variety of literary sources; for example, when Derek Nnuro came to the program, he talked a lot about Chinese literature, how he felt it was similar to African literature in various ways—certain concerns, preoccupations, and styles. When [Novuyo] Rosa Tshuma was here, she was interested in writing about Marxism. I’m really thrilled by the work of African students coming out of the program.

Annually, the Workshop admits 25 writers in fiction and 20 in poetry, from around 1,500 applications. What do you look out for?

We don’t have a quota about where people are from or what kind of writing they do. What we look for is work that is filled with energy, work that interests us. I’m sure, every year, there are many, many very good writers who go elsewhere because we don’t admit them. But we try to be very open. I would say that we look for work that excites us. Frank [Conroy] used to describe it as feeling someone reaching off the page at you when you’re reading, feeling tension in the language.

What we don’t look at is—we don’t look at who wrote your letters of recommendation, and we don’t look at where you went to college and we don’t look at how old you are or what your job is or whether you’ve published before. That’s not what we look at.

You were recently featured in Oprah Daily as one of eight “astonishing women are using their words and their platforms—their power—to open our eyes, awaken our senses, and deepen our understanding of each other and the society we live in.” There you talk about wanting “to foster a climate not of competition but of cooperation, which meant leveling the funding process so all students got the same amount of financial support.” I think of it in the context of your Literary Hub essay earlier this year, where you write about struggling to finish college, accruing $40,000 in debt, “graduating into recession,” and paying for your MFA tuition by cash-advancing your credit cards. Like you at that time, most MFA students today are “consumed by anxiety over the future.” Do you feel pressure on Iowa to stay competitive with financial packages?

We’re fortunate to be in a city that’s not as expensive as other places. We’re also aware that people will come here and they will not feel rich on the stipend. We’re trying to support people as much as we can and we’re also trying to make it possible for the program to bring in people. We’ve recently upped financial packages by several thousand dollars, and we started offering summer funding, which we’ve never done before. It’s a really big deal to try to offer summer funding to 45 people. If you give everybody $4,000, that comes up to $180,000.

A competitive financial environment fosters some writers’ improvement, while it is extremely bad for many other writers. There are many people who’ve gone through a competitive system, not just at our program but at many programs, who were silenced—not exactly by others, but they feel silenced. The reason that I wanted to make funding equal was that I remembered the effect of the unequal distribution from my time in the program as a student. It took a long time to get it right because it requires fundraising.

I feel that we could make the program a lot smaller and give more money, but if we did that then it wouldn’t be the program it is, and a lot of people wouldn’t be here. I honestly think that the size of the program is what makes it special. It’s one of the reasons that we can have such a rich community of people.

And it also makes the tradition of success sustainable over the years.

Possibly. I also think that people graduate from the program and then they form a community that’s large and open. It’s a good way for emerging writers to find a connection, an actual personal connection to other writers.

It’s interesting that you say “personal connection to other writers.” You have this beautiful essay in Food & Wine about your family. When your parents arrived in Appleton, Wisconsin, in 1965, they were the first Asian immigrants in a city of 50,000, and had to improvise with American food. With the Vietnam War, the country opened to Asian food. In The Family Chao, after the father of the restaurant family dies, locals flip and refer to his sons as “the Brothers Karamahjong”—a slur. It got me thinking in the larger terms of a certain climate of instability that non-white and non-American writers have to take in their stride—where they provide cultural value that is immediately questioned at the earliest chance. Did you ever feel, as an Asian American writer and woman, that tension between acceptance and rejection within the literary industry?

Sure. I would say that since my first book was published in 1998, the situation for Asian American writers has changed drastically, but there is still that tension.

From around that point, yeah: Ha Jin, Jhumpa Lahiri.

For every Ha Jin and Jhumpa Lahiri, there are writers who want to be seen and read and are not. One of the questions that I find it interesting to ask at this point is, why are some writers seen and others not? What is the difference between a writer who becomes the iconic writer of their generation or community and the ones who do not? What I find comforting is that this is a conversation that’s now taking place in the literary community, so there shouldn’t be just one writer from China and one writer from Korea—there should be a variety of writers from all places. I mean, for years in the United States, the book that everybody read was Things Fall Apart.

(Laughs) All over the world. I think what happens is, when there’s an accessible writer, people respond in a way that has the adverse effect of blocking other writers, because people now think, “Well, I’ve read Toni Morrison, I don’t need to read Jesmyn Ward,” “I’ve read Things Fall Apart, I don’t need to read Nuruddin Farah.” The work becomes definitive and broadly representative when it really is, great as it is, only the most visible.

But there are so many other writers. I feel that the conversation is finally starting to heat up about how to bring a variety of people in. And I want to make sure the Workshop stays a part of that.

It took the Workshop 70 years to have its first female and first non-white person as director. This is the Workshop’s 86th year. With the changes you are making, how do you see its role in American intellectual life? What do you most look forward to in the future?

I would like the Workshop to be part of increasing the variety of works, the variety of writers and stories and forms and genres that are part of American intellectual and imaginative life. I feel like what we’re doing is work in progress that, as I said, has to be recreated every year, and so I feel like I’m still working on realizing the vision that I had for this place. I would like it to establish itself, so that it’s the way people see our program.

You are currently working on something, 200 pages in so far. How is it going?

Okay, I don’t know where you found that, but I will tell you: after completing a 200-page arc of the project, I decided that I wanted to put it aside. This happened last fall, I stopped working on it. I do not think that it’s going to be my next project, and I’m going to start a new thing. I mean, this always happens in-between projects, I always have false starts.

Is it your style to find an idea first? Because when you describe how The Family Chao came about, you write that you had the conversation years ago, then you went through your notes 15 years later and started writing in a close third-person voice and then found that this was what you were doing.

I think every book has been different, but I do know that there’s a lot of fumbling around before I feel a concentrated heat in the prose that makes me understand I can move forward with it. And there’s always a period when I’m writing a novel where I feel like it’s an impossible project and I should give it up. I actually think that, if you look at most good novels, there’s something in them that is impossible; there’s a seed of impossibility, and it’s by overcoming that impossibility that the writer creates something or does something with the form. Every novel is, on some level, a potentially failed project.

In my case, I need to find something that’s interesting enough to me so that I can focus on it. My life is very busy because of my job, which is very time-consuming, so in order for me to get interested in something that is not my job, it has to guide me along or be exciting in some way. I think it’s one of the reasons that my most recent novel has a clear plot. I think the plot just helped me sort of move along; it was there, so I could come back to it after I’d been distracted by some emergency around my office or at home.

I assume that my next novel will also have some kind of plot. I don’t think it’s going to be a detective novel (laughs) or have a murder and a trial, but I think it’s going to have a pretty strong storyline.

It’s actually one of the questions I left off.

What is?

The difficulty. It’s a huge job running the Workshop, and then your writing career. Those are two very different things, being a writer, being an administrator, and yet you have somehow managed to exert all these changes while still being super productive.

Ah. But I am not super-productive. I did manage to finish a novel and I’m really grateful for that, but I consider it to be the major accomplishment of my middle age.

Finishing The Family Chao?

Yeah, I don’t expect to finish another novel in three years. I expect it’ll take me a little longer than average.

Your average was six years. All Is Forgotten, Nothing Is Lost came out in 2010, Inheritance was 2004, Hunger was 1998.

This one took me 12 years. I thought about this, you know: writers have this question about whether they should have children or not, at least a lot of the writers I know, because children are time-consuming. I was doing a book every six years, which is slower than average, then there was a 12-year gap, so my theory is that I lost a book because I had a child, which is fine—it’s a fine exchange as far as I’m concerned.

So that’s the question I left off. I mean, I feel it’s an important question to understand your writing life, but there’s a way that such a question could be perceived as—well, I wouldn’t ask it of a man.

Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah, sure.

I don’t know if treating the genders equally should mean pretending that there aren’t women who are doing extra.

You know, I happen to be lucky in that my husband is a full partner. My husband is a very kind, generous, patient person, and he does a lot with my daughter in addition to his own artistic work. I would go to residencies—the way I got this book done was go to places like McDowell, Yaddo, Berlin, Radcliffe—and he took care of our daughter while I was gone, every time. It’s not like my mother or mother-in-law came to visit; he actually did it. And he and my daughter have a really good relationship as a result of that, they’re very close, and I feel good about that. He helps me. He’s an unusual guy who deserves the acknowledgement. ♦

Lan Samantha Chang’s The Family Chao, published by W. W. Norton, is available from Bookshop.org.

More Big Stories from Open Country Mag

— Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie on Half of a Yellow Sun at 15, Her Private Losses, and Public Evolution

— How Teju Cole Opened a New Path in African Literature

— Booker Prize Winner Damon Galgut on His Novels of Masculinity, Race, Memory, and Time

— How Tsitsi Dangarembga, with Her Trilogy of Zimbabwe, Overcame

— Where Diriye Osman Draws His Flamboyance

— Maaza Mengiste‘s Chronicles of Ethiopia

— How Romeo Oriogun Became a Defining Voice in African Poetry

— Chigozie Obioma, Twice Booker Prize Finalist, on Judging the 2021 Award

— For 13 Years, Nigeria’s DSS Targeted Novelist Okey Ndibe. Now, He Might Push Back

— Ebenezer Agu on 20.35 Africa and Curating New Poetry