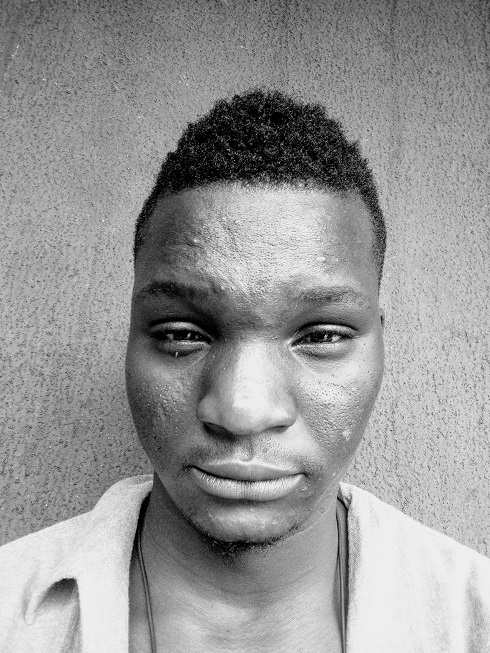

Tares Oburumu was paddling a canoe when he came upon a signboard that said: Syma. He was in the Niger Delta, where he grew up and has lived most of his life, a region full of government-owned spots and unresolved history. The spelling isn’t the sole title ascribed to his community, but Oburumu, a poet who believes in chance, was compelled to pull close. “I started asking questions and I was getting answers,” he told me. “I tried to translate it into my own experiences; I said to myself, ‘This is where I come from, and without this place, there is no Tares.’”

Last August, Oburumu’s manuscript, origins of the syma species, won the 2022 Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets. He received $1,000 and the publication of his manuscript by the University of Nebraska Press, as part of its African Poetry Book Fund Series. Praising the poems, one of the judges, Phillippa Yaa de Villiers, said that they “conjure an intimacy which draws the reader below the surface of the known world ‘where curiosity animates.’” It was Oburumu’s first real recognition in over 12 years of writing.

His relationship with poetry began even before those years. He was in primary school when he read an educational pamphlet, Henry Muwanga Barlow’s Building the Nation, and its poignant mix of outrageous comedy and social commentary stuck with him. “The expression, the diction—I was fascinated with it,” he said, “and I began asking questions about how one can put up a piece like that.”

Luckily, a teacher obliged his burning fire. The teacher introduced him to the canonical figures: Wole Soyinka, J.P. Clark, and Christopher Okigbo, who became influential in shaping his young hand. “A world was open to me,” he recalled. “I went into it and I began to see a lot of things.”

In his first five years writing, his poems were rejected, and he worried about recognition. He settled into the Facebook literary community, which peaked in the early- to mid-2010s. “Publishing on Facebook gave me a sense of belonging somewhere, in a little group of people, friends. There’s a sense of satisfaction that comes with it.”

His first chapbook, a breath of me, influenced mostly by Okigbo’s Labyrinths, was published in 2014. He wrote it in two weeks, and then lost contact with its senator patron and there was no promotion. He was constantly searching for publishing houses and wrote his other chapbooks in frustration. He had split them out from an initially planned full-length collection. His second chapbook, a brief history of July, was released through a friend based in Aba, southeastern Nigeria. Earlier this year, someday I will be the shape of my story was published by the literary magazine Afapinen.

Oburumu’s poetry bears the brunt of reality. Growing up in the southern state of Bayelsa, he says, was “like Hell.” As a child, he was instructed by his mother to bathe his immediate younger brother by the riverside, where they usually did. But then he and his elder sister lost the child, and after much wailing, someone entered the water to retrieve him. Somehow, he survived, belly full of water. Only to die two years later, as would another brother of Oburumu’s who, although not directly a victim, was, he said, “taken by water.”

“In my poetry you can see that without the reference to water, without the water metaphor, I am incomplete,” he said. “The water metaphor keeps me going, the water metaphor gives me a poetic sense of ownership. And without the water, I think anything I write wouldn’t fit into my personality.”

He studied philosophy at the University of Benin. He struggled after graduating and had to work on a construction site owned by a rich relative, where he was paid N500 for hours of heavy lifting. But he was used to hardship, turbulence, unforeseen circumstances, he told me, “the survival instincts you have to master; the hope and the dream that lives inside of you—everything is submerged in water.”

Oburumu is a poet whose language stirs the senses. He believes that experience should propel every writer. It is “something that should run parallel with tradition,” he said. “They will give you your own voice and set you apart from many others. My childhood wasn’t something I am so sad about. Whatever I’ve experienced, the trauma and emotional turmoil, I don’t think without them I would have been the writer that I am today.”

He has had to work hard jobs not just for himself but also to keep food coming for his daughter. He has had to beg for many things, including financial support and publication. But they are choices he doesn’t regret. “The act of survival, for me, is a lot more inspirational than anything,” he said at the end of a tear-inducing monologue on his earlier days, “trying to put yourself in a place where there’s no place for you.”

Now he is here, winner of a notable continental prize, with a career suddenly possible. It feels divinely scripted for a poet who isn’t a fan of contests and prizes. It was a friend that nudged him to submit.

“When it came, I was a bit confused,” he recalled. “What is happening? Is it true that prizes can also be given to people of my kind? Because I see myself as one writer that probably would amount to nothing and has to recourse to posterity alone.”

He has always created his poetry from a space of solitude, hardly sharing his work. Now he’s more aware of his chances—even if he doesn’t measure his career growth by prizes. The opportunity to travel and meet people is one he increasingly fancies. “The next step for me is not how I will be so consumed with prizes and the rest of them,” he said. “The next step for me is to give myself to writing completely.”

Support from his online acquaintances remains a propulsive force. “My family don’t even know right now that I’ve won something like this; even if I have to tell them, they wouldn’t understand,” he said. Then he added, triumphantly, “But I’ve won.” ♦

Edited by Otosirieze.

3 Responses

This is beautiful 😍❤️

A story on it’s own

I think there is a connection between pain and creativity. And Tare’s story is just another confirmation of this fact.. Congratulations to him.

The things only hardship can write. Keep soaring, man✊🏿