When I began assembling this list, I understood the small storm it might summon. Lists, after all, are not neutral instruments. They distribute attention unevenly, generate exclusions, and invite grievance from those whose work, labor, or anticipation are not named. I did not set out to produce a list I could defend on the grounds of comprehensiveness or authority. I wanted instead to curate one I could stand behind honestly, even if imperfectly, a list shaped by the limits of my reading life, my critical commitments, and the pressures of time imposed by PhD studies and everything that spills from it.

What guided me was not the fantasy of representativeness but the desire to trace a texture of African writing in the past year. African literature continues to occupy a strange positionality: frequently declared marginal, perpetually overburdened with expectation, and constantly renegotiated in the imaginations of its most devoted advocates and its most inattentive observers. This list is an attempt to read that negotiation as it unfolded across genres, geographies, and forms, without pretending that a single year, or a single reader, could hold a whole continent in view.

If 2025 proved anything, it was that African poetry remains not only alive but restlessly inventive. This was the year many long-anticipated collections finally arrived, and they did so with an assuredness that resisted the apprenticeship narrative often imposed on African poets. From Tramaine Suubi to Itiola Jones to Gbenga Adesina, poets wrote with voices that felt already tempered, already sharpened. These books negotiated space and history with confidence, insisting that African poetry can be grounded in memory without being trapped by it, attentive to geography without being confined to it.

Stella Nyanzi’s Exiled for My Mouth stands out not simply for its urgency but for how it stages the body as archive and provocation. Writing from exile, Nyanzi refuses decorum, deploying satire, rage, and vulnerability as political tools. Similarly, Abdourahman A. Waberi’s When We Only Have the Earth and Nick Makoha’s The New Carthaginians gesture toward longer historical arcs, folding ecological anxiety, migration, and classical inheritance into African poetic consciousness. Across these collections, poetry becomes less a lyric refuge than a site of confrontation, where language is asked to withstand pressure.

Prose fiction, by contrast, felt uneven. This is not to say the year was without notable novels, but rather that many arrived weighed down by expectation or curiously muted in their afterlives. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Dream Count exemplifies this tension. Its inclusion on this list is cautious. The novel is burdened by its own visibility, by the infrastructure of anticipation that surrounds Adichie’s work. In my reading, it struggles to move beyond the gravitational pull of those projections. What lingered most was not the argument of the text itself but the spectacle of its arrival. The discourse around Dream Count seemed to orbit the object more than the ideas within it. This signals what I see as a shift toward visibility culture in African literary ecosystems. Books now circulate as events, images, and metrics long before they are encountered as texts. One wonders how culturally defining Americanah might have been had it arrived in the current economy of attention, where saturation substitutes for engagement.

A quiet counterpoint to such visibility was Esther Ifesinachi Okonkwo’s The Tiny Things Are Heavier. From its opening sentence, the novel announces its ambition. It is among the few works this year that seriously reckons with the idea of the nation-state, even as its characters move through academic corridors and intimate spaces. Okonkwo’s book is attentive to scale, to how private lives are shaped by political inheritance, and how history presses itself into the smallest gestures. It is a book that trusts accumulation over spectacle, and that trust pays off. Stephanie Wambugu’s Lonely Crowds similarly resists easy consumption. The novel is alert to contemporary alienation without collapsing into sociological shorthand. Wambugu writes with restraint, allowing emotional distance and fragmentation to become formal strategies rather than thematic complaints.

Other novels on this list nod towards different experiments. Abdulrazak Gurnah’s Theft revisits his enduring concerns with memory, displacement, and moral inheritance, while Tierno Monénembo’s The Lives and Deaths of Véronique Bangoura plays with biography and historical rumor to interrogate how African lives are narrated and misremembered. Together, these novels suggest a prose landscape in search of quieter, more patient forms.

The short story collections and anthologies of 2025 provided some of the year’s most agile writing. Sefi Atta’s Indigene continues her precise excavation of class, gender, and national belonging, while Ayotola Tehingbola’s Lagos Will Be Hard for You captures the city as a site of abrasion and desire without romantic excess. These collections thrive on compression. They allow writers to test ideas, tones, and structures that novels often cannot risk, presenting the short story in especially fertile form.

Nonfiction, too, asserted itself as a crucial site of intellectual and political labor. Mahmood Mamdani’s Slow Poison is a sobering, methodical account of Ugandan state formation, reminding readers of the value of historical rigor in a moment saturated with hot takes. Minna Salami’s Can Feminism Be African? stages a necessary conversation about gender, power, and epistemology, while Dancing with Jinns, edited by Momtaza Mehri and Ellah Wakatama, opens space for African women to write against silence and constraint. These works underscore nonfiction’s role in shaping the discursive conditions within which literature is read.

It is important to acknowledge what does not appear on this list, though the reasons are less tidy than questions of genre or visibility. There were novels or poetry collections whose political intentions were unmistakable, even admirable, but whose narratives arrived too pre-assembled, too certain of their own righteousness. In those books, politics did not arise from character, structure, or tension; it blared itself, insistently and repeatedly, leaving little room for ambiguity or discovery. I found myself less persuaded not because of what these books argue, but because of how narrowly they argued it. What fell away, in such cases, was not relevance but texture. My exclusions, then, reflect a preference for work that trusts readers to encounter politics obliquely, through narrative pressure and formal risk, rather than through declaration.

Taken as a whole, this list is not a verdict on African literature in 2025 but a record of my encounter with it. If there is a throughline, it is the sense that African writing continues to resist stabilization. It moves unevenly, argues with itself, and refuses to settle into a single posture. That restlessness, even when frustrating, remains its most vital inheritance. ♦

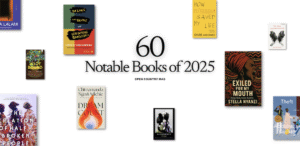

Read: Open Country Mag‘s 60 Notable Books of 2025, Guest Curated by Tolu Daniel

More Essays & Book Excerpts from Open Country Mag

— The Ahistorical Racial Polemic of Conclave, by Otosirieze

— Thinking Through Tremor, by Reyumeh Ejue

— “Our Literature Has Died Again”: Nigerian Writing in the Era of the Nomadists, by Kanyinsola Olorunnisola

— River Spirit, by Leila Aboulela

— “The Nigerian Oppression, as Chinua Achebe Would See It,” by Emmanuel Esomnofu

— The Quality of Mercy, by Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu

— Between Starshine and Clay, by Sarah Ladipo Manyika

— “Revel, Again, in the Beautiful Absurd,” by Ernest Ogunyemi

— Black and Female, by Tsitsi Dangarembga

— Sankofa, by Chibundu Onuzo

— We Once Belonged to the Sea, by Diriye Osman

— Biracial Britain: A Different Way of Looking at Race, by Remi Adekoya

— The Fugitives, by Jamal Mahjoub