In the early 1990s, after civil war broke out in Somalia, Diriye Osman and his family fled their homeland and settled in Kenya, in Nairobi. Osman, then a child, wanted to be a fashion designer (“the Somali Gianni Versace!”). He spent his days drawing illustrations and listening to R&B: Toni Braxton, Whitney Houston, Mariah Carey. He also loved reading fiction and comic books and dwelled in the worlds of C.S. Lewis and Roald Dahl, and in The Adventures of Tintin, Asterix, and Calvin and Hobbes. His mother, a gynecologist before the war, and father, a chemical engineer, gave their blessing to his dreams.

“I was this sweet-sweet camp little kid who was talented as an artist, but it didn’t endear me to my older siblings or classmates or cousins,” he tells me. “I was an unusual child, and it took me decades to realize that I suffered from depression and anxiety by dint of my sexuality. There’s nothing more threatening to bigots than a talented, emotionally intelligent, neurodivergent gay child, which is probably why there’s so much LGBT book banning in homophobic states in America right now. Information is weaponry and there’s nothing more radical than an educated pickney who understands the depth of their own power.”

It is this clear-eyed awareness that injects Osman’s oeuvre with vigour and potency. In one of the many short essays on his website, he wrote, “All my work, whether it is literary or visual, will be documents of survival.” He tells me, “I’m not supposed to be here. I have survived so many disasters, major and minor, that my being alive is a miracle. I call it ‘surviving the unspeakable.’ I’m here and I will never stop being in awe of this fact. My life is a miracle on a grand scale.”

When he was 18, a year after his family moved to London, he was diagnosed with psychosis and institutionalized in a mental hospital in Woolwich. His breakdown was triggered by him fighting to perform the intricate act of embracing his sexual orientation and pleasing his strict Muslim family—which culminated in an overwhelming sense of guilt and shame. During those six months, he briefly lost his ability to speak.

After he was released from the hospital, his mother encouraged him to apply for a library card. He fell in love with the works of Arundhati Roy, Zadie Smith, Salman Rushdie, Manil Suri, Nuruddin Farah, Alice Munro, Alison Bechdel, ZZ Packer, Edwidge Danticat, and Junot Diaz. In 2008, he began to write short stories as a way to pair the magic he learned in books with his own experiences.

Most of the stories he wrote in that period appear in his debut short story collection Fairytales for Lost Children. Set in Kenya, Somalia, and South London, the stories follow young gay and lesbian Somalis seeking freedom in the complications of family, identity, and the immigration. He elected to show a diversity of experiences because, as he put it, he “understood the syntax of politics and representation.”

But when he sent out the manuscript, “every major and minor publishing house in the UK” rejected it. He switched to the US, and Team Angelica Press published it in September 2013. His persistence paid off. The book brought him into the consciousness of literary and artistic circles. It won the 2014 Polari First Book Prize, was named one of the best books of the year by The Guardian, and received praise from Nuruddin Farah, Bernardine Evaristo, Roxane Gay, Ellah Wakatama Allfrey, and the late Binyavanga Wainaina, who called him “a new Baldwin.” Later, Dazed and OkayAfrica named him on to-watch lists and The Independent included him in its annual “Rainbow List” of “the 101 most influential lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people in Britain.”

“I was in love when I was writing that text,” he says. “It will be 10 years old next year and it is still in print. It’s being taught in high schools in Malawi and Minnesota as well as graduate programs all across the UK and the US. There are young LGBTQIA folx who have found themselves in that book and continue to do so. This makes me happy. Always choose the underdog—that’s where the radical art is being made.”

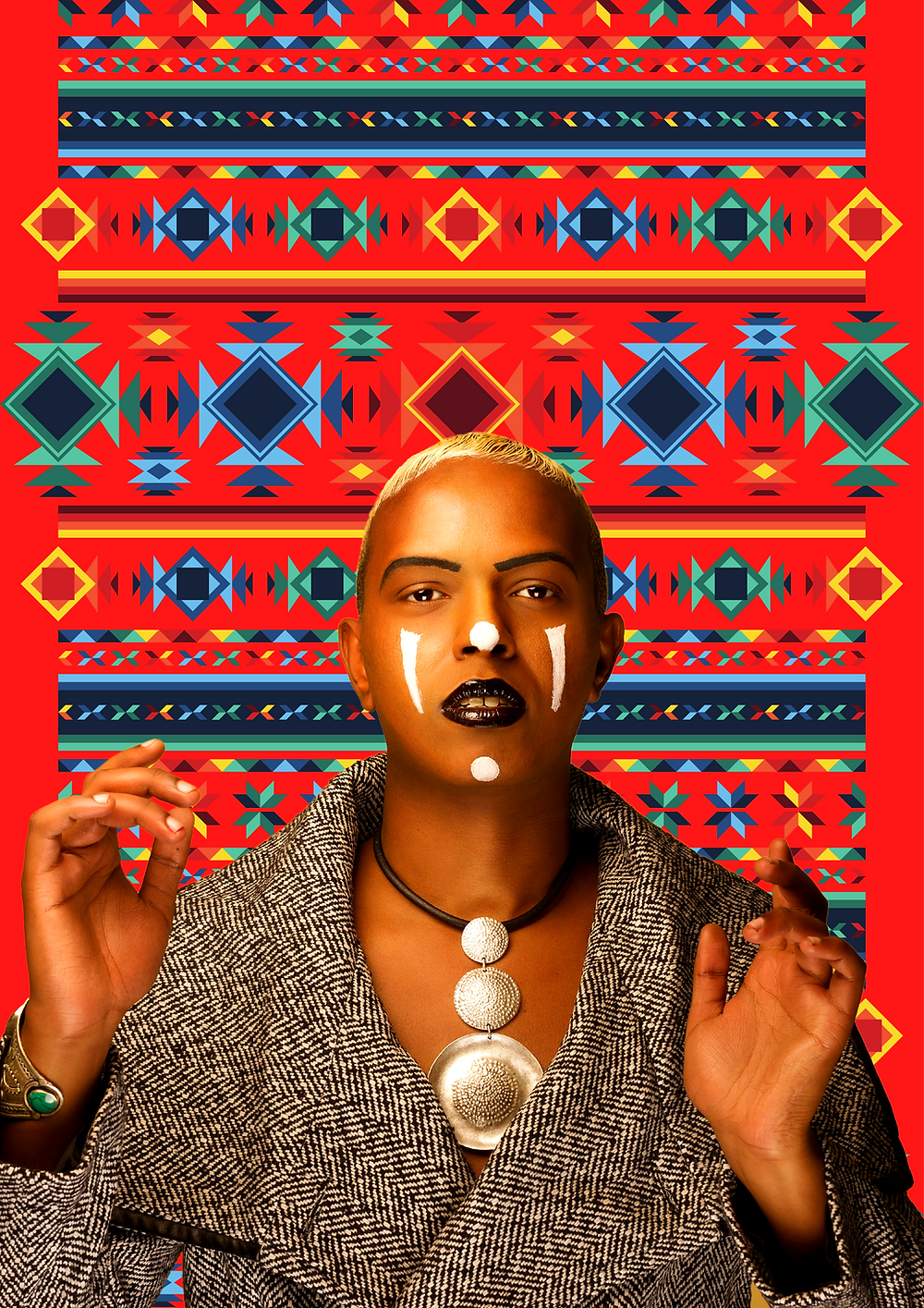

Osman, a self-described “bad bitch/good-natured motherfucker,” doesn’t only create art; he considers himself art, too. He is on the cover of Fairytales for Lost Children, draped in a lavish 15th century gown. (He is on the cover of all his books, like they are memoirs of celebration.) Such cheeky flamboyance is something he worked himself into. When he went to the costumier and was strapped into the corset, he hadn’t felt constricted as he imagined; he felt, he wrote, “sensual, beautiful, powerful, virile.” He has always believed that “femininity in men is a form of power.”

Osman’s visual art—drawings, photography—is an intriguing collage of vibrant aesthetics that pushes at the seams of what is regular: it often features goddess-like figures that luxuriate in their sexuality and male models embracing styles that disregard heteronormative perspectives. He uses 3D textile paint, glow-in-the-dark glue, temporary tattoo stickers, powder dye, and, he revealed to Beige, Swarovski crystals. He also incorporates Arabic calligraphy and Hebrew, like in the pieces The Goddess Complex – Aquatic Arabesque and At The Altar of Imagination. His major influences: Hayao Miyazaki, Walt Disney, Fritz Lang, Gustav Klimt, and H.R. Giger.

“My visual art is pure play,” Osman tells me. “But like all delightful acts of performativity, there is a seriousness there too. You simply cannot be what you cannot see. So my visual art, particularly the collages featuring me in drag, is part of my activism. It’s my way of saying, ‘We can be as weird and wonderful and brilliant and badass as we want to be.’ There are countless young black folks who send me mail about how my wonky aesthetic has helped them come to terms with their own gayness and transness—even though I’m not trans.”

Five years after Fairytales for Lost Children, Osman released his second book We Once Belonged to the Sea, in 2018. The novel follows two women—a reclusive queer Somali artist and a gifted Iranian-Somali teenage punk—whose paths cross. (We published an excerpt.) It is a story about art, friendship, ambition, memory, and loss that took two intense years to write. He worked on his phone notes app, one hundred words at a time. “It sounds strange to say this, but the writing process was akin to active prayer,” he says.

Even though Osman worked with notable professionals—the cover designer was Diego L. Rodriguez, who has worked with pop stars Shawn Mendes and Drake, and the publicist was part of the Harry Potter campaigns in the 2000s—he asked Team Angelica Press to release the novel as a limited edition, with only 20 copies in circulation. The move puzzled many people.

“I genuinely did not want to release the book simply because it was radical and strange and beautiful, and it meant too much to me. It was a book that saved my life and I didn’t want to share it with the world even though there was a lot of pressure to do so. I don’t do this for money. I write because the work serves a purpose in my life. It’s an anchoring spiritual practice. I’ve said this before but I write in order to see. I just want to see.”

In the mid-2000s, Osman worked as a jazz and hip-hop journalist, an influence that still guides him now as a novelist. “Music allows me to experience the world and my place within it with a real sense of wonder,” he says. “Music is its own exquisite lexicon. I’m a big reader, but music has offered shape and definition to my syntactical understanding of storytelling in a way that nothing else has managed to achieve.”

His authorial voice, he says, was shaped by musicians like Meshell Ndegeocello, A Tribe Called Quest, Jill Scott, and Lauryn Hill, and critics like Greg Tate, Joan Morgan, and Ann Powers. On his website, he has documented his adoration for, among others, Missy Elliott, and India Arie.

Yet Osman’s wide acknowledgement of his influences is much more: a celebration of community. He has also written about writers and artists, including Binyavanga Wainaina, Chiké Frankie Edozien, Juliane Okot Bitek, Sofia Samatar, and Wangechi Mutu. “Part of our collective duty as black artists and thinkers and critics,” he wrote in a piece on Bernardine Evaristo, “is honouring our geniuses whilst they’re still creating work.”

“I love us,” he says, “and by us, I mean our global community of black folks that stretches from Naija to NOLA to Newcastle to Nairobi. When I was writing for The Huffington Post some years ago, I featured black artists and writers and thinkers almost exclusively. I had a seat at the table and so I invited everyone to come on down and join the party.”

Osman’s new book The Butterfly Jungle, published in March, is a book of interlinked stories that fuse Somali, Spanish, Kiswahili, patois, sheng, and hip-hop slangs with a blend of poetry and letters. It is, for him, an antithesis to Fairytales for Lost Children; where the earlier book’s characters push to escape anti-queer oppression, the new book is a world in which there is no homophobia for its all-queer Muslim family and no heterosexual characters at all.

He wanted to show not just a diasporic, queer family living their lives but to also normalize queer African parenting. It was important to him that his protagonist, Migil, experience the tenderness and compassion that everyone should be shown by their families—but that queer kids often are not.

“When I was writing Fairytales for Lost Children, there were so few literary representations of queer Africans,” he says. “Sure, there were academic texts and personal histories, but very few literary representations of the realities of, and possibilities for, queer African life.”

The year it came out, 2013, was the year that Chinelo Okparanta’s Happiness, Like Water, a heralded collection about queer women, arrived. The climate was changing.

“It was a little scary because I was being approached by Netflix and Vice for in-depth tell-all documentaries,” he says. “Four times by Netflix and once by Vice. They were all interested in the personal angle of my history and how it connected to my art. I declined the offers because I felt they would be too exposing. There was an enormous pressure to be a statesman of some sort, and as someone who grew up around politics, I was terrified of messing up. This was in 2014 and there was a big narrative in the west about Africans and their respective anti-LGBT states—as well as their culturally, socially and politically backward philosophies. I thought—and still think—this was dangerous, imperialist thinking. I wanted to represent my queer siblings on my own terms—and that has been the story of my career. It’s impossible to kowtow to big corporate machines who want a messianic queer figure when hundreds of emails are pouring in every day from semi-suicidal queer teens who just want support. I just disappeared into my little bubble and it took a lot of convincing from my friends and publishers to emerge from that cocoon. It was a genuinely scary time, which is why I’m glad I pulled back—and I would do it all over again.”

He feels his first book was misunderstood. “I feel like not a single reviewer or critic understood the real theme of the book. Fairytales for Lost Children was about the desire and striving for freedom, about trying to find a language for what that freedom could mean.”

The Butterfly Jungle closes the circle, he says. “It is what happens when we finally get free. It’s a text that closely mirrors my own life now. My postman is gay, my best friend and editor is gay, my doctor is gay, my neighbours are gay. I now live in a universe where queerness—and the expression of queerness—is everywhere. Telling these stories was an act of psychological and emotional emancipation for me.” This book, he says, “might be the last book I publish.”

But his literary struggles have come with valuable lessons. “We live in a unique moment of cultural plenitude,” he says. “If you want to tell your story, tell it. Don’t wait for white gatekeepers who have always seen black voices—and certainly [black] LGBTQ voices—as a niche concern not worth paying attention to. A lot of big publishers are jumping on board the train now, but they will always see us as a trend—one that in time will be supplanted by whatever the next fad is. Build your community, connect with folks who care about you and your work within the framework of a long-term career, should you wish to pursue one. We have come so far as a black African queer community. We will not look back.”

Osman’s growing up was never like Migil’s in The Butterfly Jungle. But despite suffering discrimination from his family, which affected his mental health, he maintains a genuine understanding and empathy about the duality of humanity. He has even praised his father as a motivator whose advice helped him quit unhealthy habits.

“Heartbreak is never linear,” he says. “I’ll never get over the abuse I suffered at the hands of my family, but it doesn’t dominate the day. This is because I have my own—chosen—family now. We are repeatedly reminded to diminish our value as queer folks to appease heteronormativity, but we get to build our own lives as adults.” Joy, he has written, is “a political flex.”

All his life he had been dismissed. “I was told over and over again that I would not survive, but I’m thriving. I’m truly embracing the encroachment of my fuck-it forties, I can tell you that much. I don’t believe in legacies because legacies mean nothing to the departed, but I do believe that a full-throated, polychromatic life is my calling. I want to live in a state of sustained splendour, which in this instance means pleasure—carnal, spiritual, romantic, creative. I want to live, live, live.” ♦

The Butterfly Jungle is published in limited edition by Team Angelica Press. Buy HERE.

Edited by Otosirieze Obi-Young.

More Essential, In-depth Stories in African Literature

— Nana Nkweti on Writing Cameroonian American Experiences and Crossing Genres

— Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki’s Curation of African Speculative Fiction

— How Tsitsi Dangarembga, with Her Trilogy of Zimbabwe, Overcame

— With Novels & Images, Maaza Mengiste Is Reframing Ethiopian History

— The Methods of Damon Galgut

— Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is in a Different Place Now

— Hannah Chukwu’s Call to Help Uplift Unheard Voices

— Khadija Abdalla Bajaber on Fantasy & the Character of Kenyan Writing

— Why Tobi Eyinade Built Roving Heights, Nigeria’s Biggest Literary Bookstore