In “The Dreamer’s Litany,” the opening story of the Nigerian writer Arinze Ifeakandu’s God’s Children Are Little Broken Things, a married man meets another man on a night full of starlight and falls in love. After a life-changing act of kindness by his lover, the married man seeks it all. But he’s rejected, and not in a kind way. He’s told off with the words “Ewu Awusa”—an Igbo slang for Hausa Goat—an ethnic pejorative. It sets the stage for a book in which love, culture, desire, masculinity, and humanity commingle in present-day Nigeria, sometimes fighting each other to breathe, often to devastating consequences.

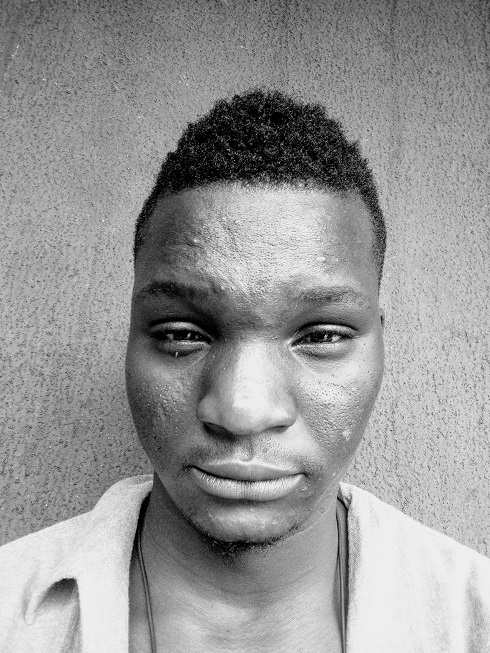

Ifeakandu’s debut has been in the works for about five years, after the title story appeared in A Public Space, whose publishing arm, A Public Space Books, acquired the manuscript. The story was shortlisted for the AKO Caine Prize in 2017, making the then 22-year-old the prize’s second youngest finalist. There has been growing buzz about his talent—with comparisons to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Zadie Smith—with him also being an influential voice in a new generation of African writers who are LGBTQ. He justifies the buzz.

Stripped to its most important relationships, God’s Children narrates youthful love in a country where being gay is difficult. Lush with evocative passages, it uncompromisingly follows the promise and pains of its characters. So real are they, you could almost reach out and touch them; so easily could you make their complications yours, untangling their excesses and poring over the minute details. Ifeakandu does not sacrifice flow; in this book, sentences curl like perfect ocean waves on a bright day.

The nuances of Nigerian homophobia hover over the stories, makes the characters move with guardedness. Several stories hold that awareness of a strong hand ready to barge in and hurt these young men. Still, Ifeakandu’s characters aren’t subdued in their nature. Flagrance follows their every step, towards the light of loving who they love.

In “Happy Is a Doing Word,” there’s remarkable progression in the relationship between Binyelum and Somadina. We’re taken into the recognizable world of kids, often playful but occasionally cruel. After naming egrets, they play in sand and crave each other’s bodies. An uncompleted building becomes their place. Who taught them to hide? The narrative voice is considerate, foreboding. Their safety is shattered:

Had they been older, and cannier, had their minds been tainted early by the world’s caprices, like the mind of a boy like Nnamdi, orphaned at three and passed around from one close relative to another distant one, they would have known how suspect they looked, two boys abandoning the gang almost every evening and wandering off on their own. But they knew nothing about the shrewd, untrusting nature of the world. And so there they were, alone in each other’s company, shorts pulled down to their ankles, and suddenly there was sound, and light, and they were no longer alone: they lay there, awkwardly, all around them eyes gawking.

As the story moves, both boys held ransom by Nnamdi’s threats, society wades in with even more resolve. Life happens and they pull apart, yanked to different parts of the country by time and preferences: Somadina, towards the acceptable heterosexual lifestyle; Binyelum, towards a tussle with his male loves, craving the innocence of what once was.

Among the book’s many threads is the disparity of experience at different ages. We follow the characters as they veer away from the relative freedom and safety of childhood, as they find themselves being observed.

There’s a longing for fullness throughout the collection. It often manifests in the limitations of family. The punchy “Mother’s Love,” a story of moral conflict, is direct in its treatment of that. “Where the Heart Sleeps” is a personal favorite, following different kinds of grief over the death of one man. A young woman, Nonye, returns to her father’s house, seeking to understand him after his death. She meets Tochukwu, her father’s lover and, according to Nonye’s mother, a typical home-wrecker. “Don’t eat or drink anything he gives you,” her mother has warned her. Yet Nonye is able to trust this man. Yet the world punctures back in. But even the story’s most heated scene is streaked with the pristine tenderness that Ifeakandu pulls off often across the collection.

From the brilliant title story to “Alobam” and “Good Intentions,” there’s a breathless sense of intimacy with the characters—I make no distinction between major and minor ones here because Ifeakandu colors everyone with remarkable humanity—it almost feels like unrestrained access into every facet of a real person. Each scene carries unmistakable purpose: to be real, to be profound.

“Good Intentions” is a poignant, perplexing tale about a lecturer in an affair with a younger male student. When word gets out, the school administration and his colleagues, who have far lesser moral standing, challenge him to a hearing that will question even his previous lovers, eager to orchestrate a public disgrace. “You could end it at dawn,” goes the story’s opening line, underlining the lecturer’s resistance. Here, Ifeakandu balances narrative depth—like the obvious power imbalance in having an affair with a much younger person—with charming wisdom.

In “Good Intentions,” as in the other stories, it is the younger lover who bears the mark of eccentricity, aware of themselves and of quirks informed by generational placement. They are often the catalysts behind the relationships’ most breathtaking and divisive moments.

Born in the arid plains of Kano but attending university in the lush greenery of Nsukka, Ifeakandu knows the potential of setting. Many scenes in God’s Children are backdropped with visual and emotive worldbuilding. The streets and their corners, the homes and their appliances, their secret histories and obvious catastrophes—all are captured in delicate, sensitive prose. The pull of his writing is its unvarnished honesty and diction. Reading this book, I could feel its skies and rooms, with all their colors and humane smells.

Ifeakandu’s own life informs the triangular movement in his setting: the characters move between Kano, Nsukka, and Lagos—a metropolis which, although represented in popular culture as a gritty symbol of Nigerian hustle, is written here with remarkable slowness. He holds down the city through the perspective of his characters.

The language and culture in God’s Children are also shaped by said perspective. The characters are mostly Igbo but the trio of major Nigerian languages naturally flows into dialogue, revealing, like in the opening story, how deeply ethnicity is sewn into the fabric of the country.

“Alobam” invokes the character of the southeast region, working the title—an Igbo slang for My Guy—to present the emotional and social complexities of a love triangle involving a man, his dead lover, and the lover’s younger brother who, once placed in the man’s care, is the recipient of his unhinged desire and headstrong protection.

In these stories, Ifeakandu also brings a great ear for sound. His sentences move with tonal deliberation, scenes paired with actual songs which act as a sort of playlist. Through this lens, God’s Children pulls together with almost the intent of a music album. It begins with a fast-paced story, then ebbs with less pomp and more sensitivity, and by the penultimate story, “Michael’s Possessions,” we understand the movement to be deliberate.

The most epic of the stories, and among the most tender, is “What the Singers Say About Love.” Two young men, going from campus lovers to big time players in the Lagos entertainment scene, are constantly cajoled into being less obvious about their intimacy. One becomes a mainstream music star and must play along with the industry norm of hypersexual heterosexuality, causing a stir in the relationship.

Not only are the stories in God’s Children sensitive, they are fresh in how they pull the peculiarities of contemporary Nigeria, from the menace of terrorism to the myriad flavors of online communities. Ifeakandu’s prose is alert to the breathing motions of living under glimmering lights and yet needing to hide one’s true self.

It is not often that debut authors are graced with the high praise Ifeakandu has received. Booker Prize winner Damon Galgut has said that his “voice is sensually alert to the human and universal in every situation.” The artistic success of this book is a testament to an incoming generation of African writers, and in time will serve as an anchor of motivation. ♦

God’s Children Are Little Broken Things by Arinze Ifeakandu is published by A Public Space Books. Buy via the site or bookshop.org.