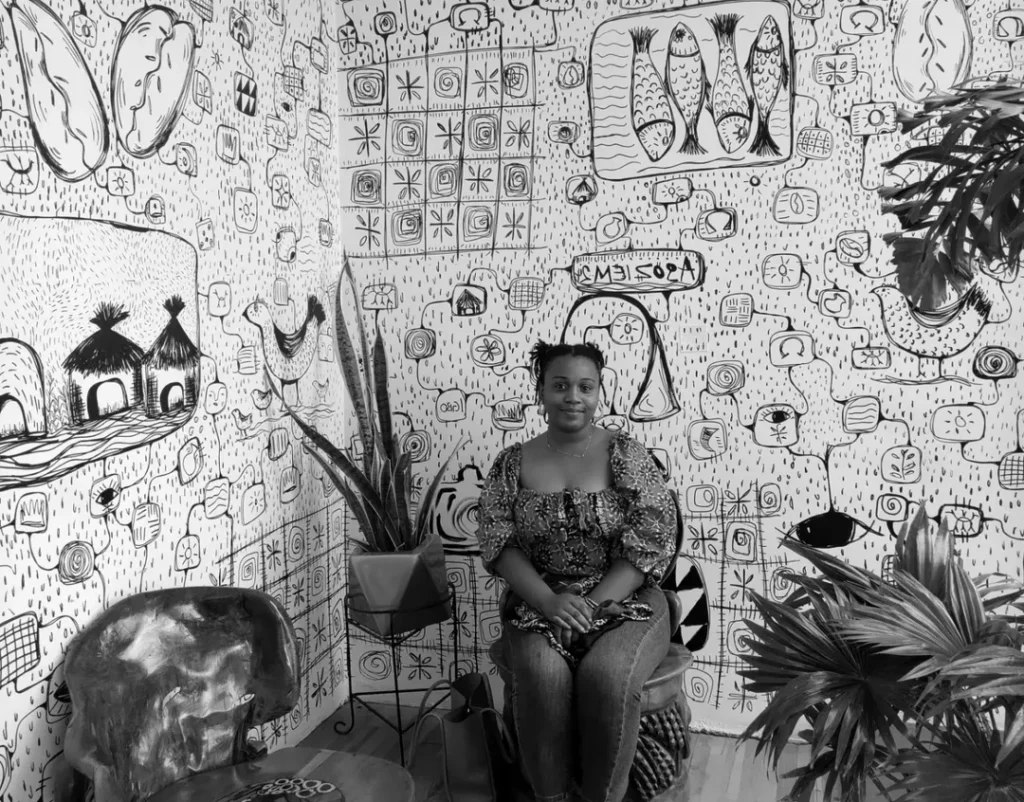

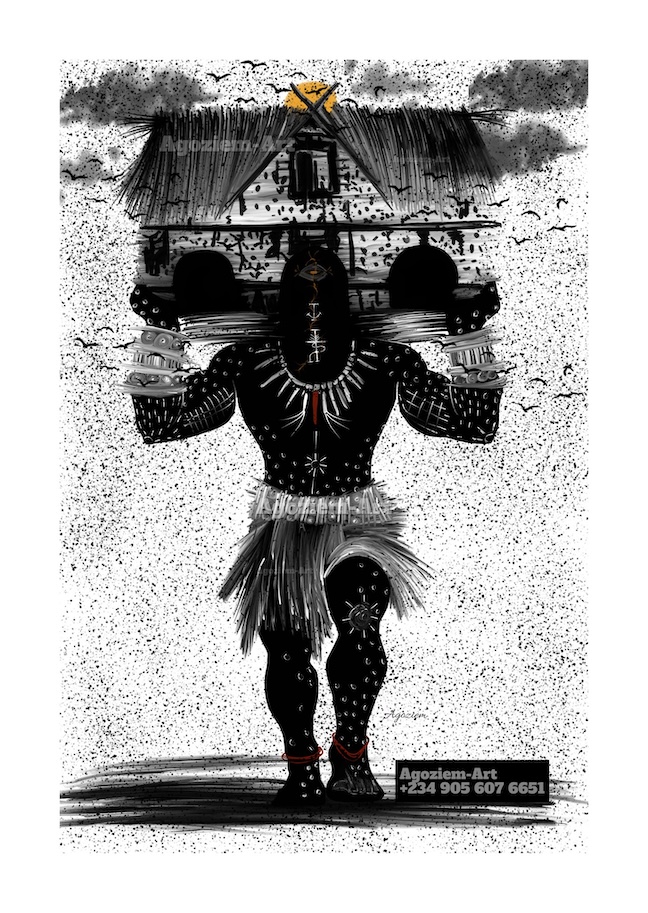

In the two-bedroom flat in Nsukka that doubles as her studio, Chiagoziem Nneamaka Orji is in her workwear, a T-shirt and combat trousers stained with paints of different colours. Around her are empty canvases, spread on the walls. On her right is a darkened jute and on it is a figure in motion, carrying a hut on its arm. In the painting, as in all her art, there are fishes, masks, cowries, and huts against a background of dotted lines, like droplets of rain. On the side of the wall, on the black drawers where she keeps her tools, are acrylic paints and pallets. In the middle of the studio are plastic chairs. By the window, a table, under which there are Igbo musical instruments, including an ubo aka, which Orji loves to play even though she doesn’t know how to. “You don’t need to know how to play it before you can enjoy it,” she says, moving around the apartment.

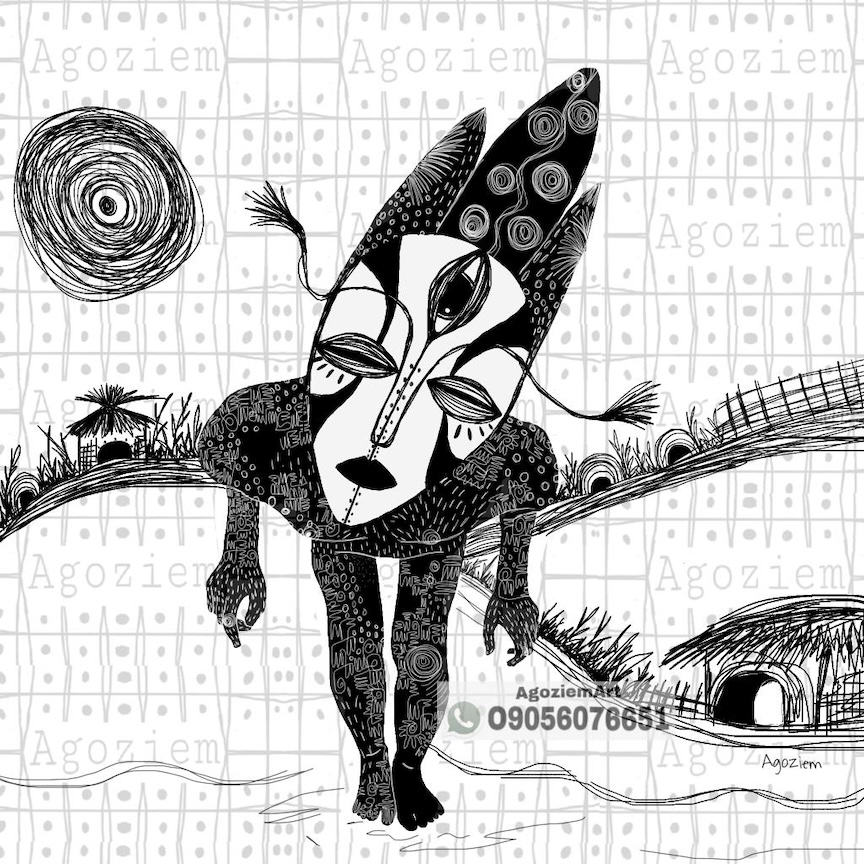

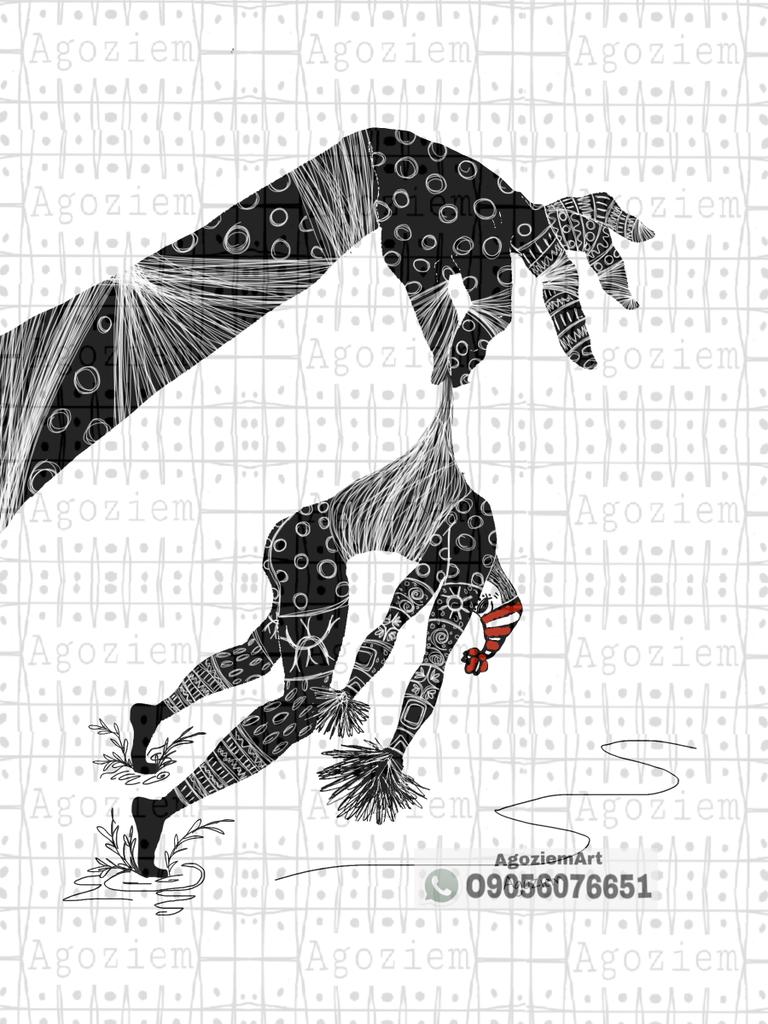

In the past year, her art works, which are deeply rooted in Igbo cosmology, have gained a following. The paintings are either depictions of prominent figures in Igbo mythology, or expressions of spirituality, or they embody the motions of Igbo theatre — in the way that Ben Enwonwu’s Agbogho Mmuo does the ceremonial dance of the maiden. It is art that has the power to awaken the native imagination, to open a portal to the locality of the Igbo civilization, in the way that Chinua Achebe’s fiction does.

The Igbo arts scene is a small but vibrant one. The artists, many of whom started in universities in the Igbo homeland of southeastern Nigeria, take inspiration from established traditions dating to the 1950s and ‘60s, including the Nsukka Art School and the New Nsukka Art School of uli artists, the Mbari Club sited in Ibadan but of Igbo impetus, and the Asele Arts Institute. Orji is a spiritual descendant of the Nsukka Art School, as is the more academically influenced Igbobinna Eze, whose exploration of Igbo cosmology in hyperrealistic and abstract paintings has helped resuscitate uli-graphy.

There are Samuel Nnorom, the textile sculptor, and Ndidi Dike, the veteran sculptor, painter, video, and mixed media artist. Chuma Anagbado’s phygital art mixes the physical and the digital to narrate stories. Among a growing number of artists working exclusively in the digital realm, converting their work to digital tokens like NFTs, is Osinachi, the continent’s leading crypto artist and an Nsukka graduate. But it is in hyperrealism that the genre produced its biggest viral stars, including Arinze Stanley, detailing pencil and charcoal portraits, and Ken Nwadiogbu, who adds bold colours to his own black-and-white paintings, as well as prodigies, like Mayor Olajide who broke out online at 17. Together, their works run the gamut of culture and identity, from the traditional subjects of mythology, politics, and colonialism, to the modern turfs of race relations, sexuality, sexism, and consumerism.

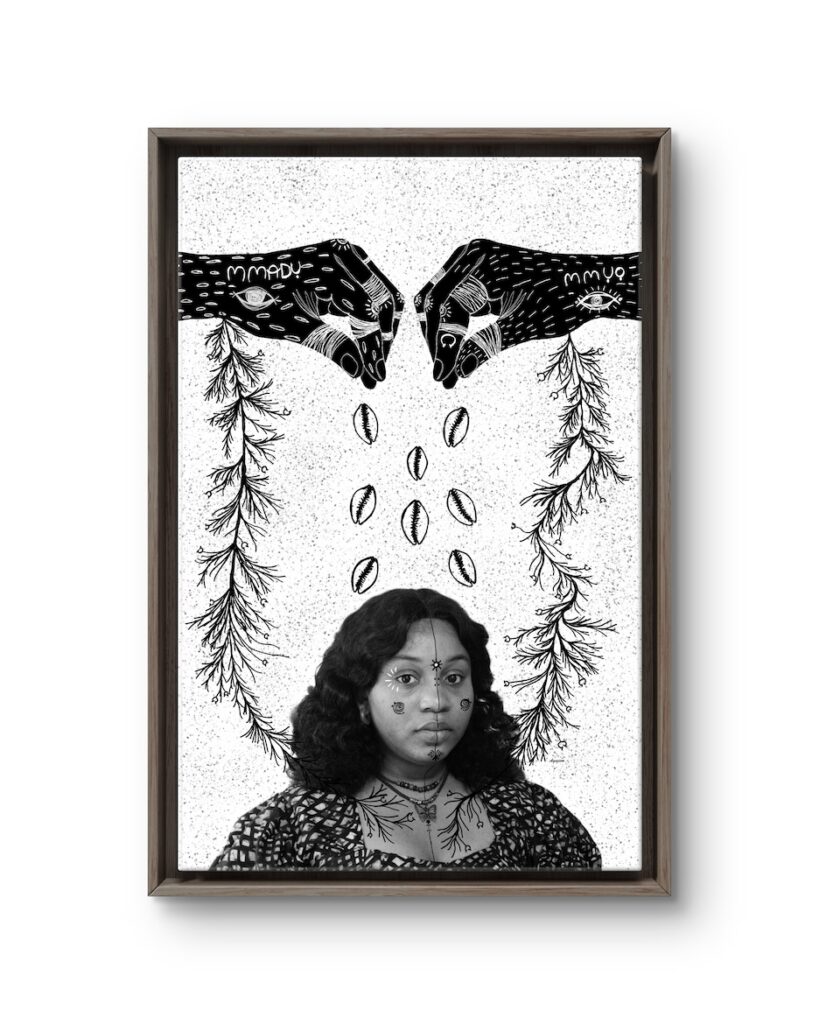

I discovered Orji’s work on Twitter. One piece, titled Adighi e Ji Anya e Ji a Fu Mmadu a Fu Mmuo (You Cannot See the Spiritual with the Same Eyes with Which You See the Physical), contains a squatting figure, holding its waist. It has large eyes of such depth, as if signifying the additional layer of consciousness needed to perceive the extra dimension of the spiritual. Looking at it makes one think of inner personhood — the effect of surrealistic art meant to release the creative potential of the subconscious.

“I am working on a series called Akuko Oji Ihe,” Orji tells me. Story of the Bearer of Light. Could the series be about the philosophy of Di Ji Ulo, the head of a household? “Oh,” she says, “because they are all carrying huts? The truth is that huts are something that have always been present in my art. They signify home. For me, home is a feeling. When we miss home, it is not just the building that we miss, it is the feeling that home gives us.” She gets back to the subject. “I have not been enjoying working on this series.”

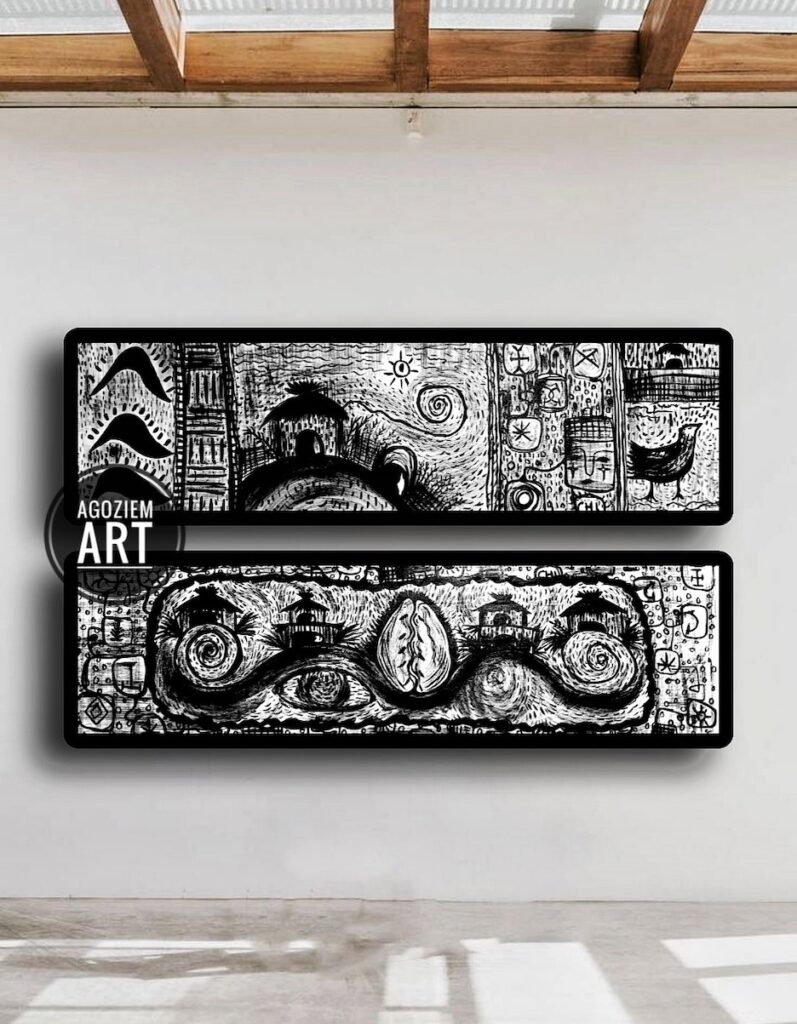

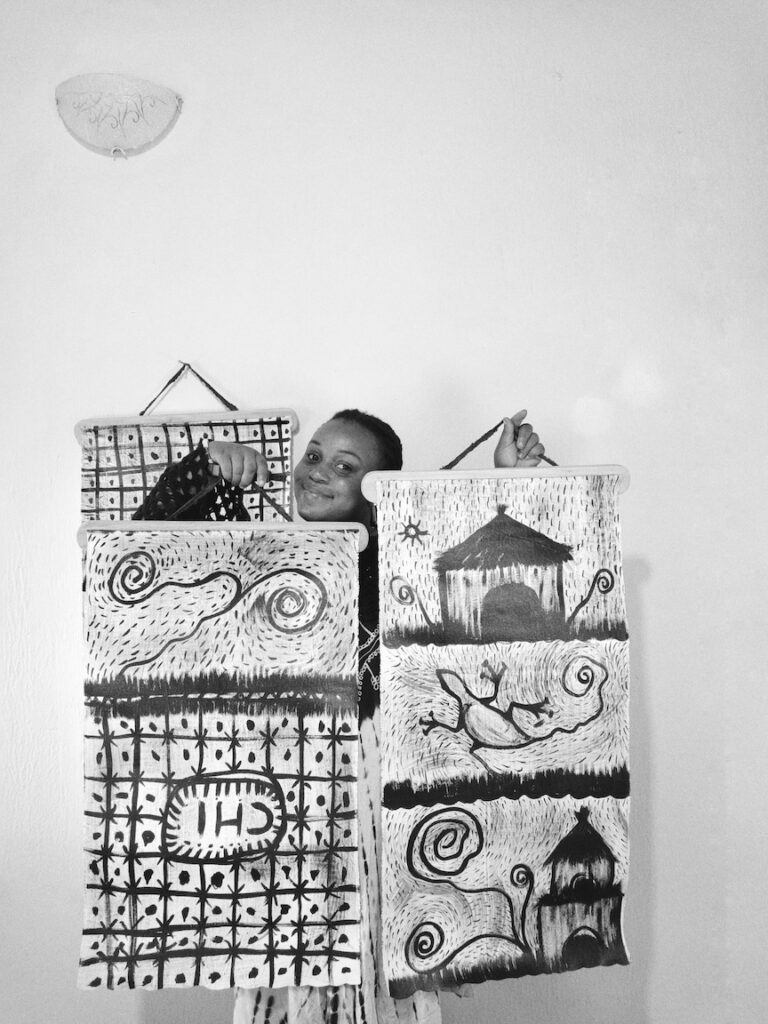

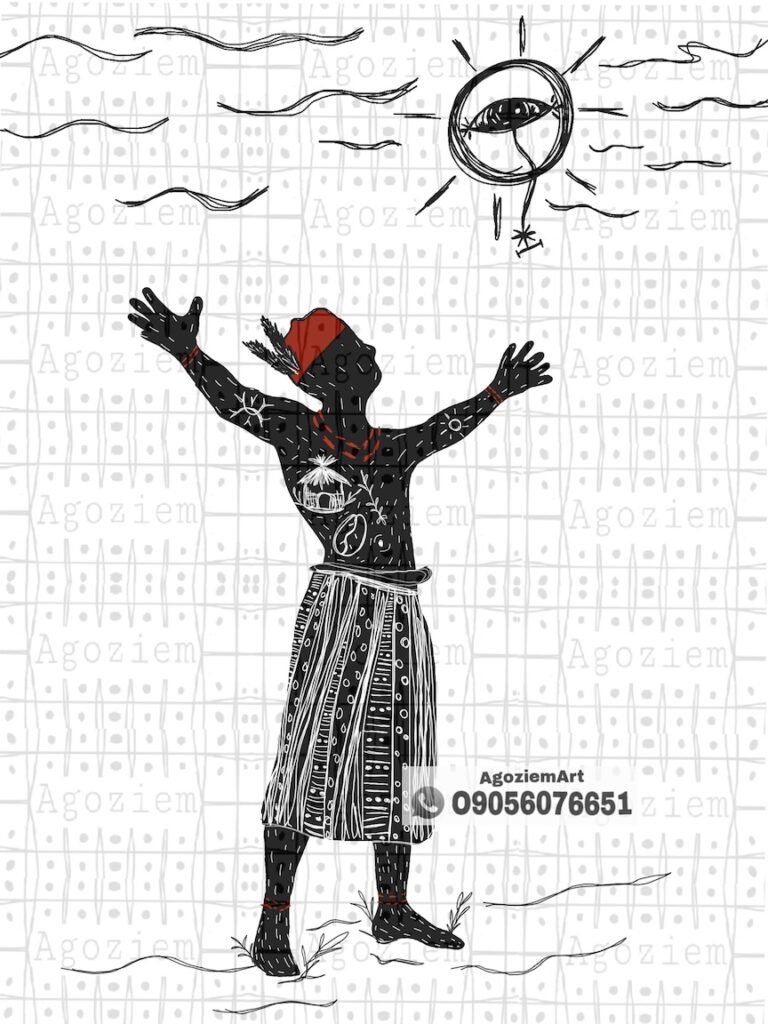

She unrolls two longer canvases, one with an image of a man, the other with a woman; both are looking up, and, in the middle, contour lines trace upwards to sunlight. The rain-like dotted lines are on a different layer from the background and the image, as are the contour lines.

“The sun is the centre of everything we do,” Orji says. “Without the sun, there would be no possibility of life. The plants get their energy from the sun, everything comes from the sun.”

Orji was born in Lagos, in 1997, and moved with her family to Enugu, where she grew up. She was drawing from a young age, on paper, on the table, on the walls of her home, on any surface. She studied Fashion at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. There, she was inspired by the uli classicist Eziafo Okaro, whose lines she finds “harmonic and rhythmic” and from whom she learned “to be creative and free, to not restrict yourself.” Also among her key influences are the Onitsha-born Enwonwu and Achebe, the former for his “movements,” the latter for “his settings and how he titles his books and how he names his characters.”

“Their works made my work more refined,” Orji says, “and it made me see more meaning in what I was doing and it made me to continue.”

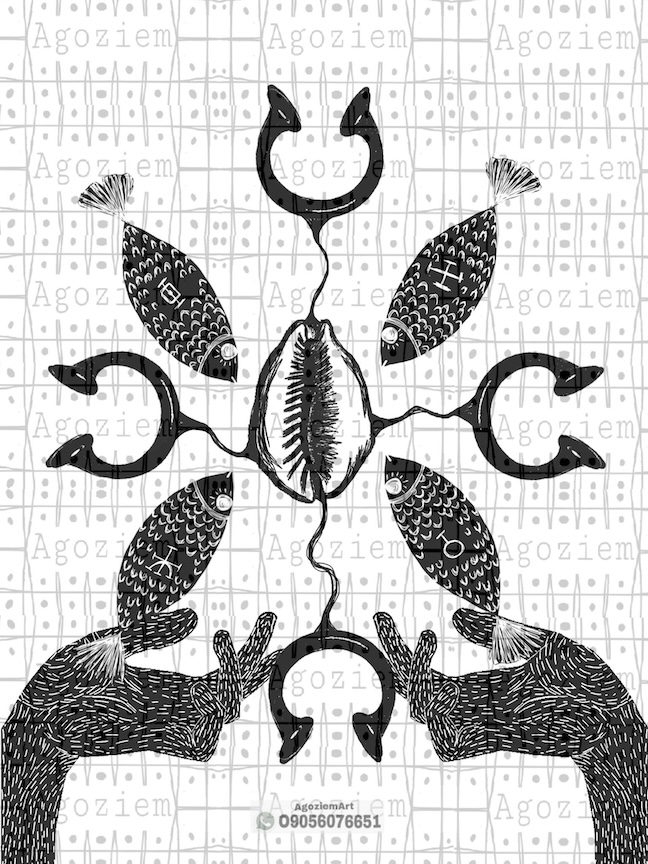

Her art has a semiotic quality: it speaks through symbols. She paints fish to represents rivers and an abundance of life and clarity, cowries to mean trade, and dancers to show ceremony. Masks, for her, are significant. “We are really just flesh outside. What we look like outside is not the same as what we look like inside. The mask represents what we put on when we come outside. The smiles, the laughter, are often not real. It is only when we are back to our hut that we put away the mask and crawl back into our real skin.”

The evolution of her symbolism is fueled by her understanding of ecology, the harmony in the world around her. “When I move somewhere new, I look at the trees, observe the kinds of birds there, know the environment. If you go to a place and you find that it is full of woods without leaves, you realize that it used to be a desert and could be marked by loneliness. The ancients were observant. You can know what kind of animals live in a particular forest. And this is how they got to understand what forests were good and evil. When they say ajofia, it is because they have observed and seen the danger in going into such forests. I am always observing and my art is about my environment.”

In a personal way, her life situation has also affected her work. Three years ago, she and her elder brother survived a frightful vehicle accident in Umuahia, on their way to Uyo for her National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) camp. It left her right arm broken, a Type 2 fracture, and her brother unconscious. For months, she underwent surgeries, requiring titanium chips to be placed under her fibula. For more months afterwards, she could not draw or paint. Unable to handle a brush, she began to explore digital drawing and painting. It was her use of a computer that nudged her to share her work on social media.

Unlike her digital art, often monochromatic with a touch of red, her manual paintings are full of colour, adding an extra layer of meaning — not only for a student of colour theory as myself but also for her thousands of social media followers who receive them as the most vivid, relatable communication of both Igboness and native art on the Nigerian Internet. In return, she invites her audience to suggest titles for new works.

Last December, Orji traveled to the ancient city of Nri, during the Igbo festive season. It was for an exhibition, entitled A Tale of a Century, aimed at depicting Igbo spirituality, fashion, politics, and economics. Her work, which opened in a section themed “Depth of Spirituality,” was given the entire ground floor, with other artists demarcated into spaces upstairs. In attendance were Nze na Ozo high chiefs and the traditional ruler of Enugwu Ukwu.

“I loved how Ndi Nze na Ozo cherished the works, but most especially the Igwe,” Orji tells me. “He let me explain every work, one by one, and he asked important questions. He took his time to absorb everything.” The implication of their pointed interest and disposition dawned on her slowly: her work did not only speak to her generation of Igbo people; it spoke also to the elders, the very custodians of her culture. ♦

Edited by Otosirieze.

If you enjoyed what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

No One Covers African Literature, Nollywood, & Industries Like Open Country Mag

— The Creed of Cardinal Arinze

— How a Spiritual Novel Influenced a Music Album: Booker Prize winner Ben Okri and Ghanaian Rapper Delasi on the Richness of African Consciousness

— Alhaji Waziri Oshomah, a Muslim Highlife Pioneer & ’70s Star, Returns for Legacy

— The Next Generation of African Literature Is on the Cover of Open Country Mag

— The Fates and Faith of Tunde Onakoya

— How Leila Aboulela Reclaimed the Heroines of Sudan

— Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is in a Different Place Now

— The Epic, Transformative Comeback of Chidi Mokeme

— Rita Dominic‘s Visions of Character

— Nonzo Bassey‘s Songs of Heartbreak

— Maaza Mengiste‘s Chronicles of Ethiopia

— Chude Jideonwo on His SARS Victims Documentary Awaiting Trial

— From Dreams of Music, Football, & TV, Bada Akintunde-Johnson Sets His Style