It was 2017 when a group of distinguished Igbo personalities, burdened by their diminishing culture, came together to found a hub that would preserve their traditions and history. The idea, engineered by the quintet of Ndidi Okonkwo-Nwuneli, Patrick Okigbo III, Nkem Nweke, Nkiru Okparaeke, and Jude Udo Ilo, drew from the Igbo philosophy of ncheta: remembrance. Ncheta Ndigbo.

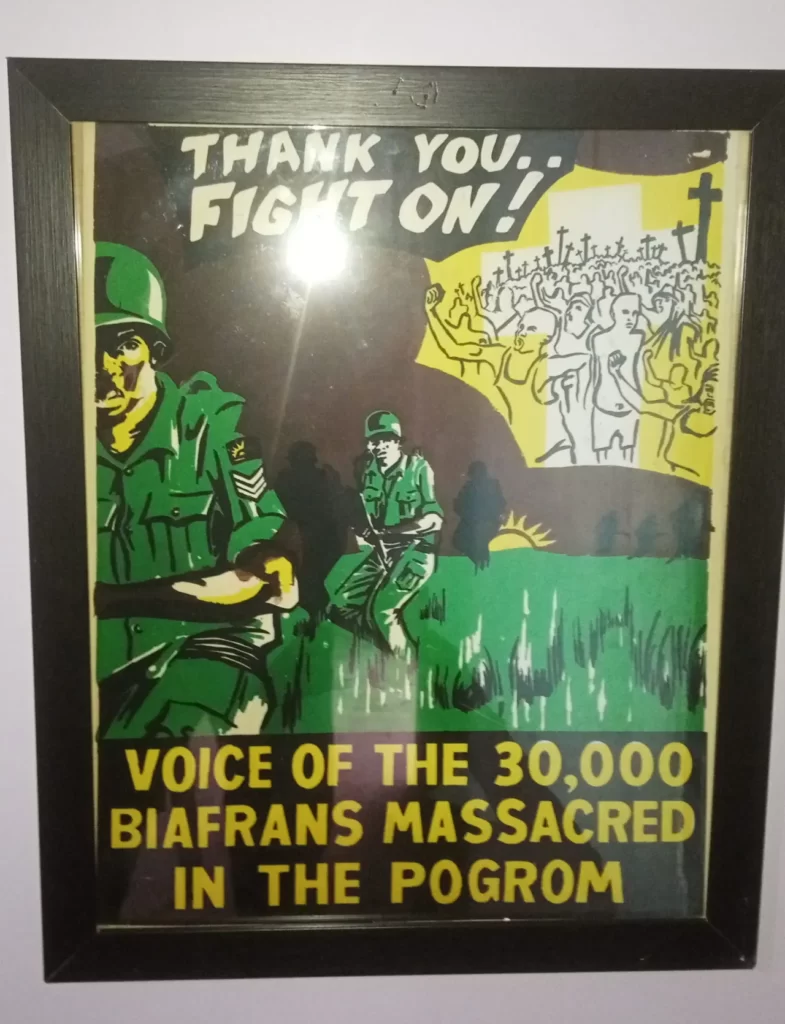

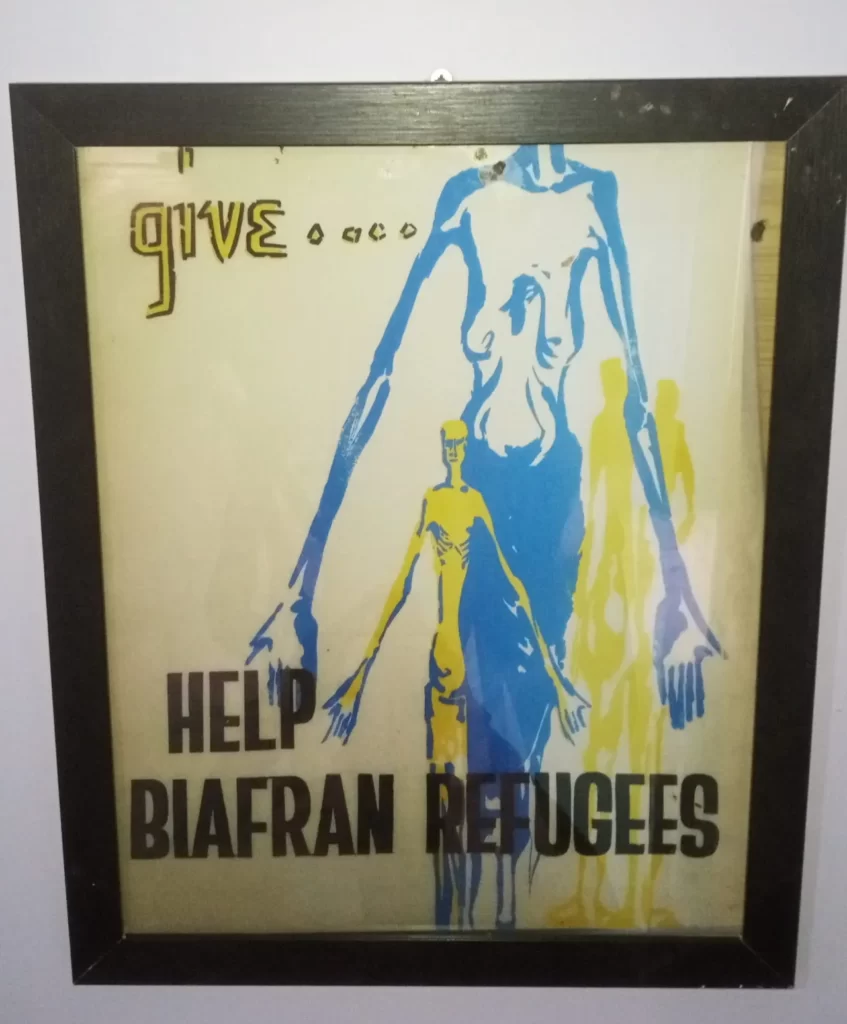

Nine years before their assembly, in 2006, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) had listed Asusu Igbo among 700 languages heading to extinction by 2050. This in itself was part of a chain of events that degenerated 40 years before, in 1966, six years after Nigeria’s Independence, when the Igbo suffered a pogrom in the north of the country. It triggered the Biafran War of 1967 to 1970, which the Igbo lost, with an estimated three million dead, mostly children, mostly from hunger. A range of subfactors, including shame from association, led to the speedy decline of Igbo speaking. Add Nigeria’s colonialist education system, in which speaking one’s native tongue was punishable, especially in the southeast, home of the Igbo.

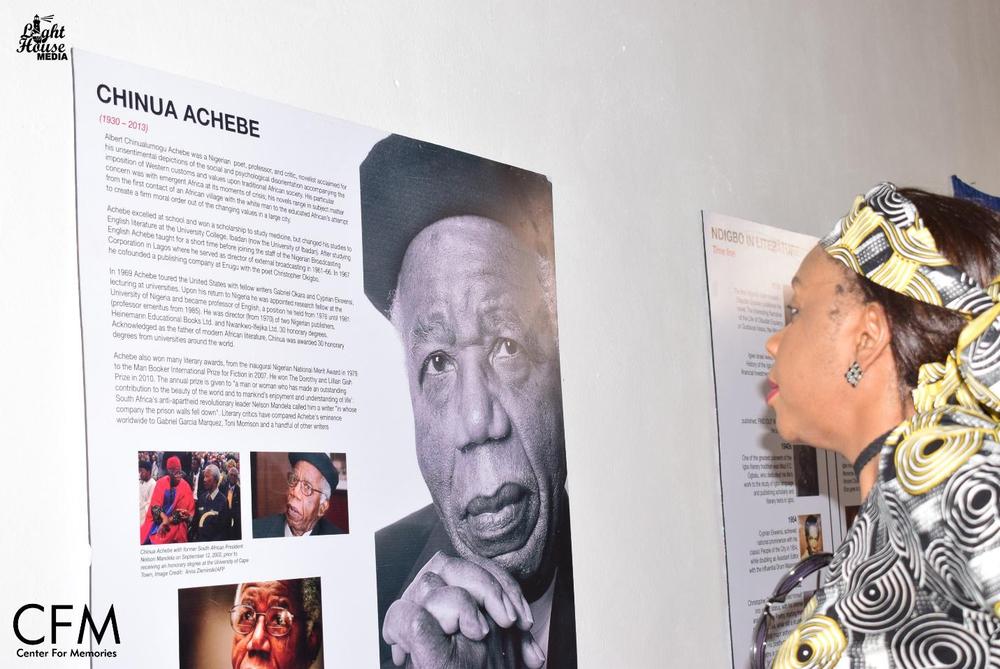

Since its founding, Centre for Memories, located in the southeastern city of Enugu, has operated with a slogan: “Maka unyaa, taa, na echi,” which translates to “For yesterday, today, and tomorrow.” It has collaborated with artists, museums, and other cultural institutions in creating exhibitions celebrating Igbo culture. It launched its first in 2018: Ola Ndi Igbo: Igbo Contributions to Nigeria and the World until 1970. It developed a permanent one: Ozoemena—Untold Memories of the Nigeria-Biafra War: 1967 – 1970 (“Ozoemena” means “May another one not happen”). It has made films and documentaries centered on Igbo stories, one of which is January 15, 1970: Untold Memories of the Nigeria-Biafra War, released in January, 2020, and nominated for the Africa Movie Academy Awards (AMAA), in the Best Documentary category.

The Centre has also held memorials for key historical moments, and hosted book clubs, readings, and speaker series with notable figures. It has formed educative programs for children, featuring Igbo language, art, and history. Despite challenges, including funding, Centre for Memories has drawn over 10,000 visitors.

The Centre’s executive director, Iheanyi Igboko, spoke to us about its work as a repertory of Igbo excellence.

The Centre for Memories is a “repository of the history and culture of Ndigbo, informing and empowering leaders to serve with excellence and integrity.” Its mission considers the transformative power of history and stories. Tell us more about your work.

The Igbo are natural-born storytellers. The visionaries who founded the Centre understand this, as well as the importance of telling history and culture in unique ways to embody and reflect our core. Our primary purpose is to conserve and promote Igbo history, language, and culture. It was inspired by the desire to help current and future generations to make better sense of their history, culture, and identity. As with the Smithsonian Museum of African American History in Washington, which tries to document American history through the lens of African Americans, the founders of the Centre wanted it to be a hub not just for documenting Nigerian history through the lens of Igbo people but for promoting excellence, creativity, innovation, and ingenuity.

The mission of the Centre, over the years, is advanced through exhibitions, scholarly research, documentaries, memorials, mentorship sessions; Ńkàtà Ụ́mụ̀ Íbè, a monthly distinguished speakers’ series; Nzuko Umuaka, for children; and a book club for adults and children. The Centre is grooming a generation of young people who are not only grounded in their history and culture but proud of their Igbo identity.

We have partnered with Alto Historical Media and Iba Ajie to produce many documentaries, including MI Power: The Legend and the Legacy, made to mark the centenary birthday of the legendary Dr. Michael Okpara, the former Premiere of the Old Eastern Region and one of Alaigbo’s finest leaders; and January 15, 1970: Untold Memories of the Nigeria-Biafra War. We plan to document as many as 10 Igbo communities, memories, and personalities in 2023.

We also intend to populate our library with every book ever written with Igbo people in focus, or by the Igbo people. This is a herculean task. But we are as committed as ever to getting this job done. These works are discussed in the Centre’s monthly book club sessions to provide scholarship, thought leadership, intergenerational conversation, and transfer of knowledge.

The Centre has held over 40 sessions of the book club for adults between January, 2018, and October, 2022. Some of these sessions also feature live book readings and conversations with authors, including Deji Yesufu, who wrote Victor Banjo: An Untold Account of the Nigeria Civil War; Ngozi Achebe, author of Onaedo; Osita Amakaeze, author of Last Carver; and Professors Okey Ndibe, Chika Unigwe, and Chigozie Obioma.

Igbo people face a number of issues today. Many young Igbo people are oblivious of key details of Igbo history; a growing number of them do not speak the language and are unaccustomed to the culture. Tell us more about these challenges and the values that are lacking.

It is not a new phenomenon. Today, most Igbo families, even though they reside in Ala Igbo, do not speak the language. Igbo cultural values are collapsing as new trends are emerging. When a language is gone, culture is gone. It means that identity has gone, too. It shows the importance of the work we do at the Centre for Memories.

We have a generation of young people who are disconnected from the past and lack knowledge of who we are as Ndigbo, what we are known for, where we have been, and what we have achieved. The Igbo are a people guided by certain values, principles, and philosophies. Values of strength in dignified labour, hard work, resilience, innovation, and excellence are at the core of who we are. Young men distinguished themselves and won their recognition in the community by hard work in farming, bravery in war, and uncommon wisdom or oratory. Unexplained wealth was questioned and often rejected. The concepts of “Onye aghana nwanne ya”—Leave no one behind—and “Igwe bu ike”—strength in number—are also central to us. These values seem to be in decline. But we have taken up the challenge to champion a renaissance.

When you come into the Centre, one of the murals is dedicated to Igbo values, layered in proverbs. We ensure that visitors spend time on our values wall. In our programming, too, we always ensure that these values are mainstreamed. The Centre for Memories has taken it as a duty to revive these values and remind the Igbo people of our unique identity.

Since 2020, the Centre for Memories has commemorated the start of the Biafran War, on May 30, 1967, the effects of which still ripple across Igbo communities today. What is the consequence of Nigeria’s relegation of the war and the lack of any major reparative measures for Igbo people?

We are still living with the effects of the Biafran War, 52 years after it ended officially. It remains a brutal and life-defining event for the Igbo and for Nigeria as a country. It is a past that cannot be swept under the carpet.

The immediate consequence of Nigeria’s relegation of the war is the deeply entrenched distrust amongst its people. This means that the country has woefully failed to move on. The Federal Government should have remembered the Biafran Genocide through an official apology, acknowledgement of wrongs, truth and reconciliation commissions, or Remembrance Day activities. A war that raged for three years, fought mainly in the Eastern Region and ravaging it, leading to a humanitarian disaster—hunger, starvation—and annihilation of a people cannot continue to be treated like a non-issue.

The Nigerian Government neither compensated those who lost loved ones and lost properties nor those who survived and returned to find their jobs taken, their properties and houses either destroyed or occupied, and their Biafran money worthless. This is the genesis of the feeling of injustice that is pervading the entire Southeast Region today, as the Nigerian government policies are seen as further economically disabling the Igbo long after the war.

No government or regime has bothered to engender national peace among ethnic groups, regions, and religions. Beyond the implementation of the Three Rs—Reconstruction, Rehabilitation, and Reintegration—introduced by the government at the end of the war in 1970, or the building of a moribund war museum in Abia State, displaying some of the armoury used by Biafran and Nigerian militaries during the war, the closest we have had was the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the Oputa Panel, in the early 2000s, to address atrocities mainly in the Niger Delta region. The state inaugurated no official commemoration of the war, save for an annual military event every January 15. These actions lack a vision of justice.

Hence, the issues linger. And like a nuclear bomb, the effects charge every day. Research has shown that even when wars are over, their negative impacts are transmitted to the next generation and keep regenerating in other conflicts. We must seek the origins of a trauma to heal a wounded present.

To foster remembrance and healing and to initiate this difficult conversation, the Centre for Memories, on February 8, 2020, opened its permanent exhibition, Ozoemena—Untold Memories of the Nigeria-Biafra War: 1967 – 1970. It constantly reminds us of the awful and sure truth: “Those who forget history are doomed to repeat it”; and we want everyone who visits the exhibition to pledge to Ozoemena—never again!

Since we opened Ozoemena, we have had Nigerians of different tribes and tongues come to learn of the horrors that occurred in this period. In quiet observance, they reflect, respect, and remember. This exhibition has brought out in Nigerians a sense of togetherness, which would invariably make room for healing. Our country is in great need of healing and I think what we do with the Ozoemena exhibition is the beginning of a very important healing process.

The Centre for Memories features poetry, photography, and songs and dance, and collaborates with artists and museums on exhibitions. What does it regard as the place of art forms in its mission to preserve Igbo history and culture?

We regard art as a catalyst for cultural and historical preservation. From time immemorial, art has been used to express beliefs and represent cultures. It was easier settling with the arts as a vehicle, because through it we come to understand our own identities on a deeper level; and when done well, art creates a sense of belonging, fostering connections to distant times, people, places, and experiences.

In performing arts, we have worked with color city, Amarachi Attamah, Siza Amah, Ijele Renaissance Theatre, Adanta Cultural Dance, Ogene Igbo, and Ibiam Ude to express different ideas and educate our audience. We have opened numerous exhibitions, collaborating with Philips Akwari on the photographic narrative of the Abiriba culture, Ifesinachi Nwanyanwu on Nka na Uzu—A Journey into Igbo Ingenuity Through Arts and Architecture; Chuma Anagbado on Mmuo—Igbo Masquerading, Spirituality, Performance, and Visual Resonance.

We have also partnered with many institutions, including The Reentanglements Project of the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) of University of London, on the Odinani: Igbo Cosmology and Spirituality exhibition; Slapanice Muzeum in the Czech Republic, on deposition and management of artefacts; Oxford University, on the Nigeria Railway Heritage Project; and Welt Museum in Austria, on museology.

Beyond the purpose of documentation, we use diverse art forms to initiate conversations and pass unique Igbo (hi)stories and culture down to the younger generation. Young people are hugely disconnected from their history and culture. But they are showing a growing interest in learning. The Centre for Memories has provided a safe space for them to have these difficult conversations, framed by history and culture, through art. We will continue to express our works through different art forms to retain the attention of these young people. ♦

Otosirieze contributed to this story.

More Essential, In-depth Stories in African Literature and Nigerian Film & TV

— Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is in a Different Place Now

— With Novels & Images, Maaza Mengiste Is Reframing Ethiopian History

— Awaiting Trial: Families of SARS Victims Speak in Devastating Documentary

— The Making of Mami Wata, Nigeria’s First Film to Premiere at Sundance

— How Dakore Egbuson and Tony Okungbowa Traverse Trauma in YE!

— Mark Gevisser’s Long Mission of Queer Visibility

— How Lanaire Aderemi Adapted Women’s Resistance into Art

— Writing Omo Ghetto: The Saga, Nollywood’s Highest Grossing Film of All-Time

— Country Love Depicts Tenderness in LGBTQ Lives