In secondary school, Nnamdi Ehirim wrote five stories in a hardcover notebook. He showed the collection, titled “Love, Thrills, and Midnight Shrills,” to a few of his classmates, who read and praised his ability. Before then, at 10, he had written rap lyrics and held aspirations of being an emcee, like his favourites—Nas, DMX, Eminem, and Jay-Z. This confluence of literature and music began to power him.

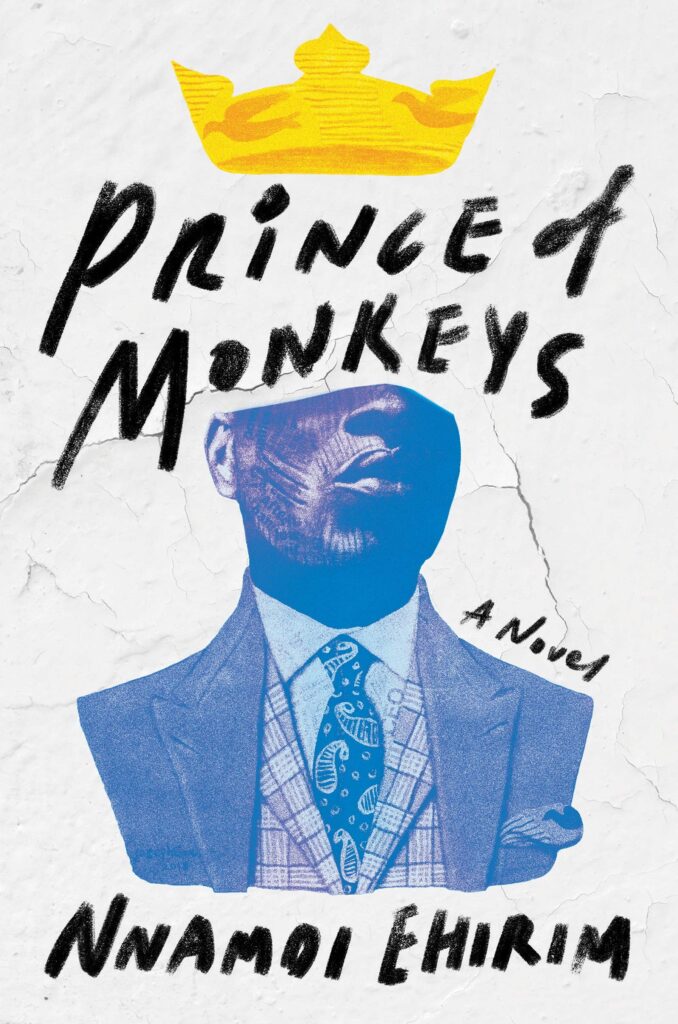

While growing up in the city of Enugu, in southeastern Nigeria, Ehirim, through his mother’s bookstore, student-to-student book exchanges, and the school library, was exposed to a wide range of literature: Christian books, crime fiction, thriller, romance novels, and classic American short story collections. In April 2014, while in his final year studying Civil Engineering at Covenant University, he began working on a novel manuscript, which became his debut novel Prince of Monkeys, published by Counterpoint Press in 2019.

“Its inspiration was a process,” he told me. “I had always written as a means of escapism from stress with life, school, relationships. At the time I began writing the book, I was looking for something to relax with as I worked on my final year project. I decided on a theme that would allow me to document my own personal ideological evolution.”

Set in mid-1980s and late-’90s Lagos, Prince of Monkeys is a coming-of-age tale about four teenage friends, who grow into adulthood in a city charged with political tension. The book also addresses class, spirituality, and power. Publishers Weekly called it “a vivid, astute portrait of Nigeria—and its people—in the throes of upheaval.” Kirkus Reviews wrote that it is “told in beautifully evocative prose. . . a panoramic novel showing that the price of growing beyond one’s origins might be steeper than anticipated.”

Ehirim finished Prince of Monkeys in January 2016. “There were two different two-month intervals during which I did no writing,” he recalled. “The process was very freeform and organic. I didn’t have access to any formal literary education or organized workshops, so I was doing a lot of experimentation and allowing my friends in school, who were big on books, to review and provide feedback after every 20 pages or so. I had also never even published a short story, so there wasn’t any pressure of writing what could appeal to publishers, because, honestly, that was a far-fetched possibility. That allowed me to write primarily for myself.”

Music helped. He found that most artists on his playlist were about his age and, at the time, unknown to mainstream audiences—Isaiah Rashad, Chance the Rapper, SZA. He drew inspiration from these parallels: he was an unknown, putting his creativity on the page with no care if the world would give a hoot about it.

In an unpublished essay that he shared with me, he explores his idea of his stories as mixtapes. “Over the years, I have discovered, fallen in love with, and constantly revisited—as I would my favorite rappers—the shorts of Fitzgerald and Faulkner, the plays of Oscar Wilde, and the semi-autobiographical works of Henry Miller, always arriving at the conclusion that most classic writers could easily be rappers in these contemporary times,” he writes in it.

“What would be the verdict if we honestly probe for any significant difference between Miller and Eminem? Both are wily wordsmiths, promoters of perverse passions, and connoisseurs of controversy who have drawn the rage of society in its entirety: citizenry, church, and even Congress. Is Fitzgerald’s contrastive depictions of a generation’s youthful and ambitious musings and adventures amidst raw poverty and vain opulence across his body of work more vivid than Jay-Z’s exploration of similar themes in a different generation?” His position is that, like literature, rap is “worthy of creative theft by contemporary writers.” Few would disagree.

“It’s crucial,” he told me of his love for music. “It mostly helps create a mood for productivity. If I can find a song or a list of songs that evoke a feeling similar to what I want to depict, I totally rinse the songs before writing because it puts me in the right mind frame. I also listen to music with witty or prose-like lyricism, so that’s mostly rap, but could also be anything from R&B to alternative music. I’ve lost the actual original playlist I used for Prince of Monkeys but I have the complete playlist of about every song I rinsed while writing my most recent manuscript, and it’s about nine hours long, touches on nearly every genre, and has a few songs that even go as far back as the 70s.”

It is a larger conversation on how writers are influenced. “The exploits of young writers allow younger writers to dream bigger,” he noted. “Achebe made guys like Adichie and Teju Cole imagine what could be possible. Adichie and Teju Cole have done all sorts of interesting things with words across many different media and that expanded the horizon of my generation.”

The future of African literature, Ehirim estimates, is radiant. “Now people are doing more than novels and short stories. People are carving niches writing on history, music, photography. All of this is only going to serve as a catalyst for more. What we define as ‘African literature’ would be stretched beyond recognition.” ♦

“Nnamdi Ehirim Writes from Music” appears in The Next Generation special issue of Open Country Mag, profiling 16 writers and curators who have influenced African literary culture in the last five years, curated and edited by Otosirieze Obi-Young. The issue comes with two covers, designed by Emmimade Design Agency.

4 Responses