When Italy’s fascist dictator Benito Mussolini marched his army into Ethiopia in 1935, he came with men who were enticed by a message: they could have beautiful Ethiopian women as spoil. The men marched in, singing about the women, carrying cameras to document what promised to be an adventure, a hope to reimagine themselves in the lives of the women, as masters and takers.

The Second Italo-Abyssinian War had begun: Italy’s attempt to redeem nationalistic pride and repair the European sense of racial superiority, both of which had been badly damaged in the First war, in the Battle of Adwa in 1896, where Ethiopian forces routed the Italians. A precursor to World War II (1939-45), the Italian aggression lasted six years until the country’s defeat in 1941 by the Allied Forces, restoring Ethiopia as Africa’s only remaining indigenous sovereign state.

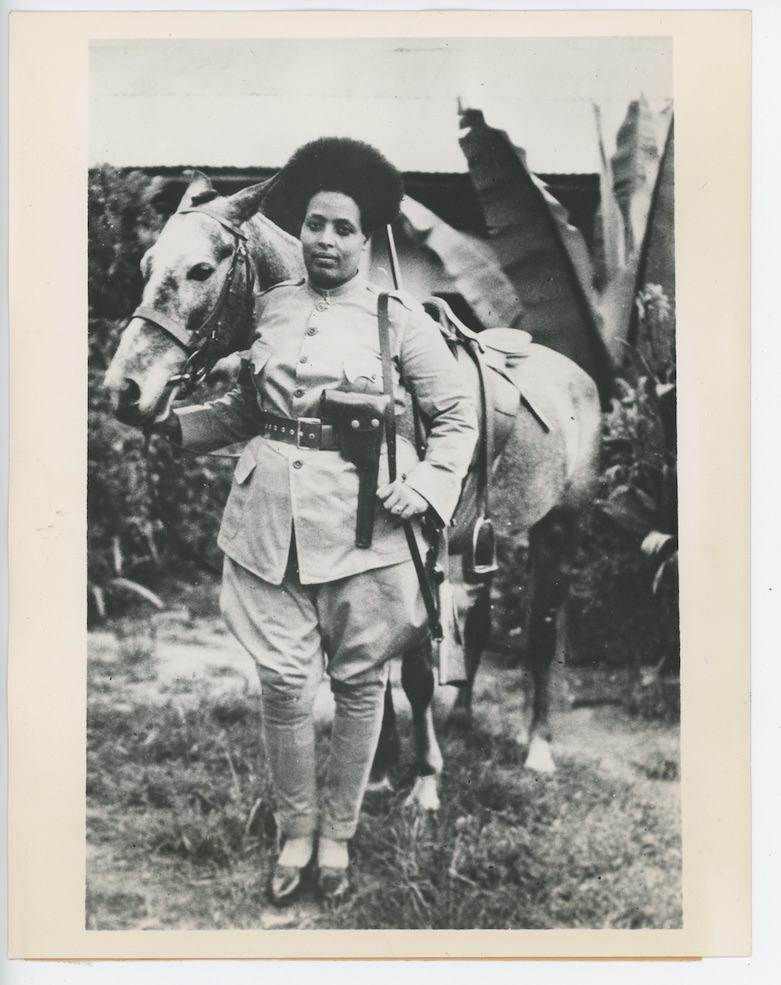

Days into the Italian invasion, a young Ethiopian girl took her father to court. Her father would not let her join the army, as Emperor Haile Selassie mandated for eldest sons, because she was a woman. Rather, he gave the family rifle to her arranged husband. The girl won, and, in court, raised the rifle in song.

The girl, Getey, would have a daughter, Maaza, who would have a daughter, Abeba, who would have her own daughter, Maaza Mengiste, who would set her second novel, The Shadow King, in this period. Rendered in gorgeous prose, The Shadow King has as protagonists the Ethiopian women whose fates were being carved out by the Italian soldiers but who instead, as the emperor goes into exile and the country’s morale falls, undertake the protection of the emperor’s double. It arms the women with political motivations of their own, sidestepping the secondary roles traditionally assigned to their gender in great war novels.

All the stories Mengiste heard of the war growing up was of what the men did; and she wanted to change how, as Svetlana Alexievich put it, “Everything we know about war, we know from ‘a man’s voice.’” But she did not know about her great-grandmother’s story until much later.

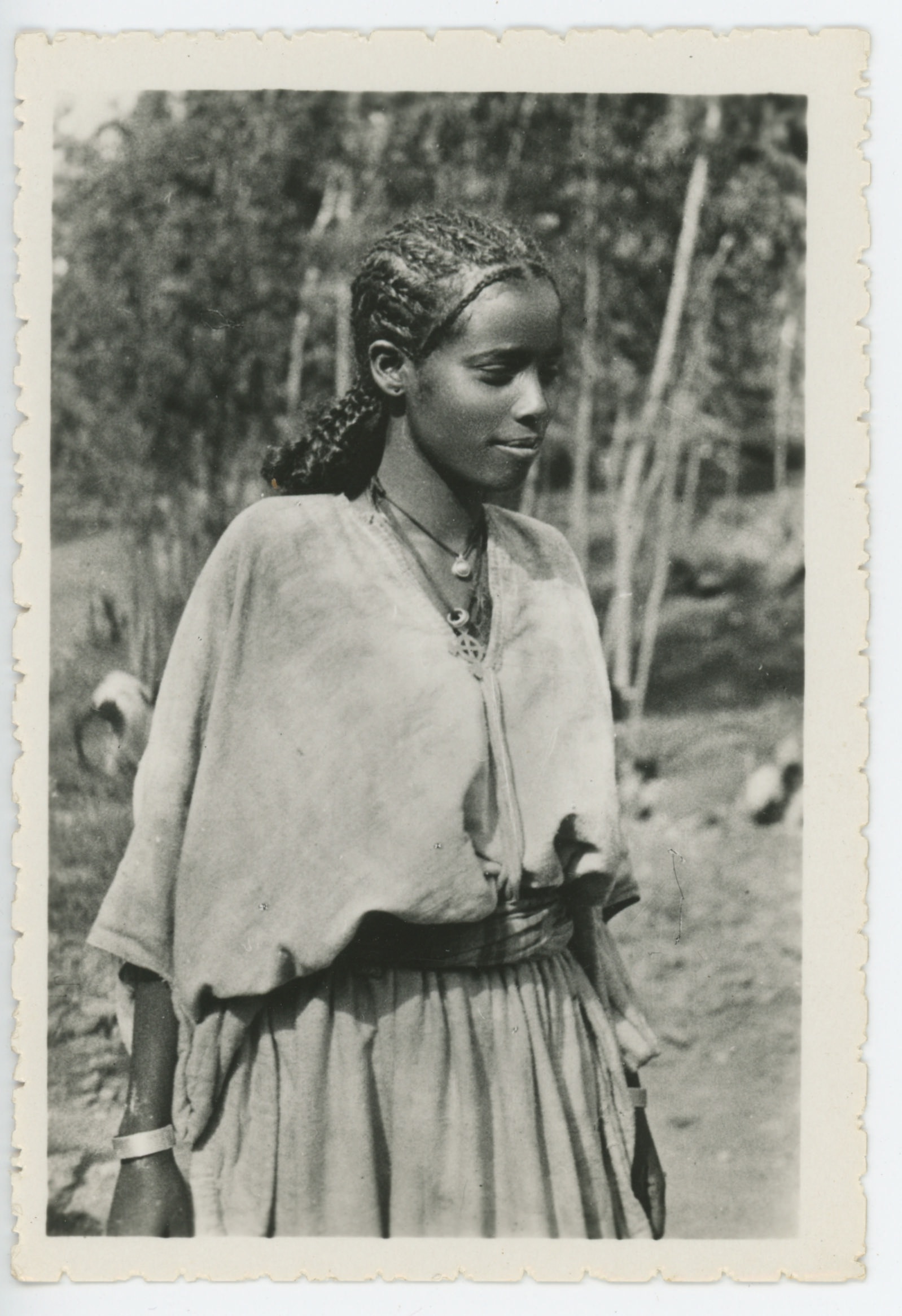

Mengiste’s idea for the novel came instead from an old photograph in her family library, itself a collection produced by the Italian invaders. The girl in the photo looks quiet, with eyes of innocence and experience. Mengiste named her Hirut, presumed her orphaned, and made her the heroine of the story.

“When I looked at the photographs, I wanted the people inside them to begin to speak back to the European holding the camera,” Mengiste tells me on a Zoom call in early December. “I was writing my characters looking at the photos. Sometimes they would speak to me. I would recognize a character, seeing them as similar to how this person is holding themselves, is moving in the image. With the photo of the girl, I really felt that this was the way Hirut might have moved in the world.”

That photo now appears in Project 3541 (named after the starting and ending years of the war), an archive of images that Mengiste is curating, reexamining the meetings of communal histories and personal memories, how they have been shaped by the collective silence that besieged Ethiopia from the war.

Maaza Mengiste, 47, is a literary latecomer. “I did not know that I could be a writer until I was 20 and I didn’t meet a writer until I was 33,” she says. “The idea of a writer was not part of the framing of my world.” Her world was framed by movement.

Born in 1974, the year of the Ethiopian Revolution, which cost her three uncles, her family fled Addis Ababa four years later and came to Ikeja, Lagos, Nigeria, where Mengiste began school and learning English. Later, they moved to Kenya, and then to the US, where she got a Fulbright Scholarship to Italy.

In the intervening years, she read Homer’s Illiad and Ama Ata Aidoo’s Our Sister Killjoy; the later, she wrote in The Guardian, “blew open my conceptions of what a book could do and what subjects it could address.” Then back in the US, at New York University’s MFA program, she met her first author.

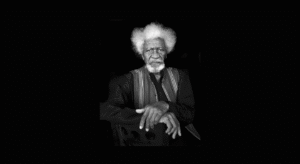

It was Breyten Breytenbach, her art professor. A South African, Breytenbach was also a poet and had been jailed during the anti-Apartheid movement. “He understood what literature could say about violence, what literature could say about history,” Mengiste tells me.

When she was stuck writing her debut novel, 2010’s Beneath the Lion’s Gaze, when, as she writes in Guernica, she “felt [she] had no language to address those ghosts” and doubted fiction’s ability to carry sturdy facts, it was to Breytenbach that she went. “He was the one I would talk to—how do you write a book about Ethiopian history in fiction? Is fiction the best way to tell the story of a revolution? All of the questions I had. He was the one who helped me initially.”

Beneath the Lion’s Gaze opens with Hailu, a doctor and patriarch of the story’s central family, treating a protester shot by Emperor Selassie’s forces (Selassie is unnamed in the novel). It proceeds to show, through his, his dying wife’s, and his sons Yonas and Dawit’s eyes, the violent coming apart of a country and the fall of its worshipped monarch, the last in a 3,000-year-old line, a rule replaced by the murderous Marxist-Leninist regime, the Derg.

A finalist for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize, Beneath the Lion’s Gaze established Mengiste among foreign-based, 2000s-blooming Ethiopian writers exploring the country’s history. At the time, they included Dinaw Mengestu with The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears, the physician Abraham Verghese with the bestselling Cutting for Stone, and Nega Mezlakia with the memoir Notes from the Hyena’s Belly, among others.

In an interview with Africa in Words, Mengiste offers an explanation for the relatively late arrival of internationalist Ethiopian writers in English. “Look at Ghana or Nigeria and their availability in the United States and England and wherever English is spoken,” she said. “Think about the history of migration in Ethiopia. People were not leaving until the mid-70s. We’re just coming into a generation, or maybe the second generation now, of the children of these immigrants in the US who are beginning to explore the liberal arts.”

It was while touring Beneath the Lion’s Gaze, in 2011, that Mengiste had the idea to go back further in time for her next book. In a bookstore in a small town in Calabria, southern Italy, an Italian man stood up and said, “I would like to talk to you about 1935.”

In that moment, Mengiste writes in The Guardian, “the entire room tensed up.” Reason: many of the foot soldiers in Mussolini’s invading army of 1935 came from Calabria. Ignoring grumblers, the man continued: “My father dropped poison on your people. How do I ask for forgiveness?”

My God, Mengiste thought as the man began to cry, this history is not done, this war feels distant but is not distant. She knew, too, that, unlike in her first book, she would name Haile Selassie in this one.

The first draft of The Shadow King didn’t work and Mengiste threw it away. For the new version, her primary research included stories of women warriors in history. “Artemisia of Caria in 480 BC to the women in the army of the Kingdom of Dahomey in early 18th century Benin, to the more recent Yazidi women’s army that fought against ISIS,” she writes in Literary Hub.

But she needed more soul, so she went back to Ethiopia, to the sites of those battles, and began asking her mother Abeba questions. “But don’t you know about Getey, your great-grand mother?” Abeba asked. “Don’t you remember?”

Mengiste was stunned. “Why did you never tell me this?” she asked.

“Well, you never asked.”

Mengiste was struck that her Hirut-in-a-photo lived exactly the same time as her grandmother Geyet. She had been redeeming her family story without knowing it; filling a gap that had been deliberately, through the politics of gender, dug out of history itself. Ethiopian women did fight against the Italians. It was a fact, no longer just her fictional imagination.

As Mengiste wrote, she ventured into another great Ethiopian tradition: music. “We have these groups of musicians called the Azmari,” she tells me. “They live in villages, have their own bars. Inside they tell stories about the village, about what’s happening in the neighbourhood. They are like griots. In 1935, they were singing about the battles, about people who were heroic. Music was also used just before battle. Warriors would gather and sing, dance, about what they would do on the battlefield. They got their blood going and charged at the enemy.”

She was writing the book as a song, as a layer of emotions, and she included a scene where Emperor Selassie listens to Giuseppe Verdi’s opera “Aida” while thinking of battle. “Music is intrinsic to many aspects of life in Ethiopia. I wanted to reflect that, incorporate that into the story,” she tells me. “When I was writing, I was listening to Mahmud Ahmed, Teddy Afro, Gigi, Aster Aweke. I would go online and listen to old-old music.”

A New York Times review of The Shadow King, by the Zambian novelist Namwali Serpell, praises how it “manages to solve the riddle of how to sing war now,” with its women “celebrated in rhetoric usually reserved for male warriors.” The Guardian, naming it a Book of the Year, called it “a necessary act of historical reclamation.” The Washington Post said “masterpiece” and TIME named it a “must-read book of 2019.”

Then one morning in late July, the lockdown still in place across the US, Mengiste was drinking coffee in her New York City apartment, listening to the news, when her UK editor at Canongate, Jo Dingley, called to say the novel had been longlisted for the Booker Prize for Fiction. Three months later, it was shortlisted.

It was the first time an Ethiopian was shortlisted. And with Zimbabwe’s Tsitsi Dangarembga up for her This Mournable Body, it was also the first time that two African women were finalists. Remarkably, she and Dangarembga were the only two out of the final six to not be debut novelists.

The Shadow King is also about memories, how they are preserved and framed, and this is because Mengiste did not merely rely on the photographs for inspiration, she also subverted their intention. “The way the colonialists went into Africa with photographers and illustrators, they were rendering images to begin to speak of not the African but the European,” she says. “Those photographs, they were made to convince them that their Europe was better than anything in Africa. Photography, like the written word, can be manipulated. It can craft one kind of narrative that completely erases another. We’ve seen the consequences across the world.”

All the photos in Project 3541 fall into this category. “The thing with a photo that is seductive, we could look at it in an instant and assume that what we see is exactly the reality. We have to fight against that impulse. We have to come at it from different angles. That takes time and work.”

But “every life lived is in a sense a refutation of that narrative,” Mengiste continues. Her new way of looking at the photos in Project 3541 is “past responding to colonialism. It is in response to creating a future fully and wholly made by Africans, for Africans. We need to look at history not in terms of correcting it but to build the future.”

As a child, she had seen this future in the photos on her family home’s walls. “Our parents, or relatives, high school photos, weddings. My grandfather or grandmother. I’d look at the difference between the image and the real human being. I was always fascinated by that gap. Photographs as constructed stories of human beings.”

I ask her about photography as motivation for creativity and she references Malick Sidibe, and begins to talk about contemporary African photographers. “I see an eye that is looking towards the future. I see people who are thinking about ways imagination can push forward more complicated and more open discourses about the possibilities of African lives.”

Mengiste’s other recent project is the 14-story anthology Addis Ababa Noir, which she edited, and which features her compatriots Mahtem Shifferaw, Sulaiman Addonai, Meron Hadero, Hannah Giorgis, and Linda Yohannes, among others. “I wanted to look at Addis as a unique city and as a microcosm of the country,” Mengiste says of her approach. “The stories really captured that, from different parts of the city, experiences, moments in history, voices. It was wonderful to see the variety.”

She has a fondness for other African cities she has been to. “Zanzibar. Hargeysa. Abuja. Lagos. Nairobi. All of those cities mean something special to me. There’s a level of intensity in Africa that comes from a passion that is historic.”

In a year in which her chronicles of Ethiopia’s past have gained wider readership, the present is getting uglier. In November, Ethiopia’s prime minister Abiy Ahmed, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019, announced that his government would invade the Tigray region, plunging Africa’s second most populous country to war. Meanwhile, in the continent’s most populous, Nigeria, an unprecedented mass demonstration against police brutality and for reformation of governance, #EndSARS, ended when the military opened fire on unarmed protesters, killing some. In Cameroon, the Anglophone Crisis has left deaths in its wake. In DR Congo, the world seems desensitized to the killings. And in Zimbabwe, her fellow Booker finalist Dangarembga was arrested for joining a street protest.

“It’s been devastating to see what’s happening across the continent,” Mengiste says. “It’s impossible for me to think about what’s happening in Africa without thinking of what’s happening in the US. It’s been a difficult year for the world. It’s been a difficult year for Ethiopia. My heart is broken for Nigeria. Our future is in those young people the government is afraid of.”

With the images of Project 3541 reframing Ethiopia’s history of resistance, Mengiste hopes to “connect people in different movements across Africa. How can a young Nigerian begin to speak to someone in Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, South Africa? Because those authoritarians are speaking to each other. They are all communicating; why are we not communicating and taking lessons from each other? If there’s anything I’ve taken from 2020, it’s that you cannot crush hope, you cannot crush that defiance searching for justice. The people who are continuing to fight, they are heroes, in the way that we speak of war heroes.”

As Mengiste speaks, her cadence brings to my mind two images in the archive. There are the Ethiopian soldiers marching barefoot, rifles pointed skywards, with no time or space to talk to each other. And there is the woman in a ceremonial cape, her pose regal, her eyes determined in the knowledge of what must be done, a story that must be retold. ♦

This story was first published with the title “With Novels & Images, Maaza Mengiste Is Reframing Ethiopian History.”

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

Buy Maaza Mengiste’s books. Open Country Mag may earn an affiliate commission from Amazon.

More Essential, In-depth Stories in African Literature

— Nigerian Literature Needed Editors. Two Women Stepped in To Groom Them

— How Tsitsi Dangarembga, with Her Trilogy of Zimbabwe, Overcame

— Hannah Chukwu’s Call to Help Uplift Unheard Voices

— How Lanaire Aderemi Adapted Women’s Resistance into Art

22 Responses