I. Love, in Art

________

Howard M-B Maximus is a Cameroonian writer and scientist.

“Fireflies,” a two-line work by the Tanzanian poet Lydia Kasese, has to be one of my favorites. In those lines, Kasese manages to depict beauty, serenity, and touch. All of which are heartfelt, whether interpreted with ambiguity or specificity, literally or figuratively. Or even spiritually. To me, “Fireflies” is the perfect example of less is more, and I go back to it every now and again:

I saw fireflies in an open field in Morogoro.

And you were there touching me.

________

David Nnanna Ikpo is a Nigerian lawyer and storyteller. He is the author of Fimisile Forever, shortlisted for the LAMBDA Award for Best Gay Fiction 2018.

If love were a movie, it would be the Nollywood film The Meeting. It subtly addresses gerontophilia, that once the legal age of consent is crossed there are really no generational limits to love. The climaxes, for me, are the two times Ejura and Makinde dance together. Here are two people—worlds, generations, cultures, and familiarities apart—finding safety, laughter, and warmth in each other’s company. I enjoyed how my mum smiled through the whole movie.

I love anything with Genevieve Nnaji in it. There is a way that I experience her being in the presence of a love interest. She holds them in her eyes, and more securely and firmly than women are generally expected to. No matter what she does when she is in love, my experience of her acting is as saying: I’ve got you. I first saw her in the Nollywood film Power of Love, in low cropped hair and a number of bootcut jeans, and I have watched almost everything else up to her most recent film Lionheart, where she is mostly in high heels and teal dresses.

I love Jeta Amata’s movies and how his men have flames in their eyes, like in Amazing Grace and in Black November. In these films, intimacy is portrayed by characters who express their love outside the safe boxes that people of their gender and race may generally romanticize but feel unsafe with in real life. I always enjoy that Jeta allows his women to be strong and his men to be held and loved and avenged.

I love the love from the outsider looking in, like in the works of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and the journalist Randy Shilts. Adichie’s portrayal of love seems to me intensely voyeuristic, and desire and participation with the observer are worlds more gripping than whatever is being observed. It is not so much what is going on but the perception of it. In Half of a Yellow Sun, it is not so much that Ugwu is watching or feeling as it is the arresting experience of Ugwu’s watching and feeling.

Shilts does this in The Mayor of Castro Street, where he describes the complex personality of Harvey Milk, in his loving and dreaming, and in his nurturing and co-alcoholism. It is not difficult to fall in love with a storyteller who is at once enthralled and infinitely forgiving and trusting of his subject. Such storytellers give me the license to transgress into becoming one with them, becoming one with the “madness” that is their entrapment until they are done—like a dominatrix who knows what she is doing.

I enjoy how love in these works is shown as having and holding as safely, liberatingly, and kindly as possible.

________

Frances Ogamba is a Nigerian writer.

Celie and Shug in The Colour Purple by Alice Walker:

The novel spirals to life when Shug makes that strange and sickly appearance at Celie’s home. Celie, who has, for most of her life, been unaware of her individuality, begins to court new desires of being visible and loved. She nurses Shug to health, guarding her like a hesitant flame. The stunning twist in their relationship is wildly unlike the typical outcomes of a wife meeting her husband’s mistress. The differences between Shug, a popular singer, and Celie, a subdued wife who has only known ugliness all her life, weave through social classes, family backgrounds, and life experiences. It is almost impossible to court any hope for Celie whose heart aches unendingly for Shug. She does not mind that they share her husband (Albert). She only minds that Shug does not love her as much as she loves the man they share. In her turmoil, Celie questions the cogency of her feelings:

He (Albert) love looking at Shug. I love looking at Shug.

But Shug don’t love looking at but one of us. Him.

But that the way it spose to be. I know that. But if that so, why my heart hurt me so.

In the end, it is Shug who leads Celie down the path of lovemaking, unveiling a hallway inside of her, a room full of colours.

Nic and Birdie in “Birdie” by Lauren Groff:

I have deeply mused on the intricate history of the two girls, now women, with one of them, Birdie, dying in this short story. Birdie pens a secret letter to Nic’s parents when they are 13, to say that Nic touched her in an intimate way. It is not that Birdie is not a full participant in their love moments, but a malice born from a tick of irritation has possessed her who is not yet fully aware of her sexual capabilities. In Birdie’s final hours, the two women are on the bed, time stretching between them. Birdie dies a week after Nic’s visit, and it turns out that Nic’s forgiveness for Birdie is reserved for two versions of Birdie. The swollen, nearly dead Birdie. And the Birdie with the warm skin sharing Nic’s sleeping bag at 13: “There were only two forgivable Birdies. All the Birdies in between, all those bitches, still had something to answer for.”

This rage in Nic caps her love for Birdie. It is so moving and so complexly human.

________

Okwudili Nebeolisa’s poetry has appeared four times in The Threepenny Review. He is an MFA student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

One thing synonymous with love is desire. Richard Siken’s debut poetry collection, Crush, is rife with it. Of all kinds: ravishing, passionate, and even kinky. It reminds me of the kind of fire you feel when you’ve met someone on an app and you finally meet them in person and the whole thing clicks. (If Garth Greenwell’s What Belongs to You were a poetry book, it would look like Crush.) This book is full of gay sex. It’s an unabashed declaration of the speaker’s love for the other person, in the finest language possible. Language so beautiful. Unlike in most poetry books, it doesn’t attempt to sound deeply wise. It even embraces self-love as its own religion. When Siken writes that “the entire history of human desire takes about seventy minutes to tell,” you sort of feel that’s the duration needed to race through the book, the entire history of the writer’s desire for this one man. Coming back to it alone was like coming back to a love letter.

________

Jennifer Chinenye Emelife is a PhD student in Curriculum and Pedagogy at the University of Toronto who misses reading African novels.

A love story that easily comes to my mind is Zulu Sofola’s play Wedlock of the Gods. I read that as a young adult and I remember thinking that the lead characters, Ogwoma and Uloko, must have really loved each other to defy tradition, even if it meant them dying. My absolute love story isn’t exactly romance: the beautiful friendship between Ramatoulaye and Aissatou in Mariama Ba’s So Long a Letter. A line stands out to me in the novella: “Friendship resists time, which wearies and severs couples. It has heights unknown to love.”

There are also the steaming affair between Ifemelu and Obinze in Chimamanda Adichie’s Americanah and the biracial love between Tayo and Vanessa in Sarah Ladipo Mayinka’s In Dependence. The love described in most Buchi Emechata novels is mostly borne out of duty: to husband and to children. I’m rereading this and it occurs to me that all of these love stories are told by female writers. I’m wondering if it is just my bias or are the men not writing about love? LOL.

________

Megan Ross is a writer and editor from South Africa. She is the poetry editor of Isele Magazine and the author of Milk Fever (uHlanga, 2018).

My favourite love story is actually a memoir, but, surprisingly, it contains no great human love interests. A House of My Own: Stories from My Life is a great love story of culture, of art, of the written word, and of self. In it, Sandra Cisneros writes of her life’s work, her ambitions, and the many lives that she inhabits in one. At the centre is herself, all heart and soul, and she is unashamedly direct in her love song to her independence—she is, after all, to quote her, nobody’s mother and nobody’s wife. This book reminds me that love is in and of itself a powerful energy that is open to everyone; that it requires no object of affection, only a heart.

________

Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki is the author of the climate fiction novelette O2 Arena. He has won the Horror Writers Association diversity grant, and the Otherwise, Nommo, and British Fantasy Awards. He edited the first-ever Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction anthology, and co-edited the acclaimed Dominion (2020) and Africa Risen (Tordotcom, 2022) anthologies.

My favourite love story is cynically and ironically about love gone wrong. And I do believe, not to be too negative, that love always goes wrong. Even in the event of no foul play by either party, there are fouls okayed by life. But better to have loved and lost than not to have loved at all, right?

That is why Vendetta: A Story of One Forgotten by Marie Corelli will always be enduring and unforgettable for me. Even though many say it is about revenge more than about love. You see, revenge was only the end of the story. The beginning and heart of it was love. Love for his best friend, wife, and child. Until a plague, a pandemic much like the one we face now, leads to a near tragedy and a deadly revelation that spurs him down a dark path.

________

Adikinyi Otsomo Kondo is based in Nairobi. She writes creatively and academically. Find her artistic endeavours on her website adikinyi.co.ke.

I will not tell you that love is something that can be broken down and understood like an algebra equation. It’s a crazy thing. “Swallowing Ice” by Nana Nyarko Boateng is a short story that shows how crazy it can be. It’s about a woman in love. She describes the touch of his tongue on her clitoris, the way his body curves into hers. She gives him milk every day. When away, she misses him deeply. She teases him with what he likes most, in places where she likes the most. She opens up to him about her life, her problems, failures, successes.

One day, he goes missing. Her life stops in its tracks. To see and care and to have that given back in equal or abundant measure? She knew he loved her, too.

So why did he leave her?

Who was he? Her cat.

________

Tsholofelo Wesi’s work has appeared in Prufrock, Ja mag, and the Go the Way Your Blood Beats anthology.

Mhudi by Sol Plaatje hit close to home. Barolong goes from one tragedy to another. The dread is bearable because of the couple at the centre. It’s based on real historical events, and though the reader knows where the story is headed, the dynamic between Mhudi and Ra-thaga gives this illusion of hope that things might turn out differently. History, as we tell it today, does not feel so inevitable when witnessed through this relationship, especially the eponymous character.

“A Road Called Love” by Sibongile Fisher is a short story I think about a lot. It has this atmosphere that I keep coming back to. It gives shape to the alienation that comes with sharing a private world with someone who can easily pop that bubble.

I’d completely forgotten about Zakes Mda’s The Whale Caller until I had to think about love stories. The book was poignant because of what was happening in my life at the time. The premise is a love triangle between a woman, a man, and a whale. I don’t remember a lot that happens in it, but it would be interesting to reread.

________

Carey Baraka is a writer from Kisumu, Kenya. He sings for a secret choir in Nairobi.

Ndinda Kioko’s Wasafiri Prize-winning short story “Some Freedom Dreams” is one I have read and reread and reread and reread. The narrator and Samira and Ras. Or is that Samira and the narrator, and the narrator and Ras? Ras who the narrator was always leaving. It’s Ras I cling to. Kioko writes, “Six years before, it was just Ras and me. We were trying to be poets. No one wanted our EngLit degrees, so we wrote poetry and mailed it to ourselves. They were poems about everything and nothing, poems about loving and eating and dying.”

It’s not a very happy marriage, Ras and the narrator. The narrator and Samira feels more natural, feels to me like what draws the narrator to the truest version of herself. But I, me, the reader, mimi, also have an EngLit degree that no one wants and write poetry that I mail to myself and dream of freedom and that Ras and the narrator were me, in their individual selves and also together. But she was always leaving Ras; even when he died, she was always leaving Ras.

________

Tramaine Suubi is a Ugandan American graduate student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and a lover of all things water.

Before I knew what it was, I was writing and reciting poetry. Some of my own poems were planted by stories that took root in my head and my heart. They span several cultures, periods, and genres, but they are also platonic and romantic. I guarantee at least one of them will light you up or completely wreck you too.

My first one is a South African poem, “sthhandwa sami (my beloved isiZulu),” by Yrsa Daley-Ward. It is my favorite love poem of all time, and the speaker captures the ache I felt when I was falling in love with my partner. The second is a Ugandan short story, “Jambula Tree,” by Monica Arac de Nyeko. As Anyango writes to Sanyu, the subtle power of their love blooms with every detail and it changed my life.

There is the iconic love story of two best friends, Issa and Molly, in Insecure. The series felt like the closest mirror of my best friend and I, and when the finale aired, I sobbed. Another iconic U.S. television show, Jane the Virgin, weaves the intergenerational love story of a Venezuelan American writer, her mother, and her grandmother. Jane, Xiomara, and Alba are well-rounded women who share such a unique and powerful love. Their dynamic is complicated, hilarious, and resonant for me as a first-born immigrant daughter. Black Mirror is my favorite television show of all time, and “San Junipero” (season 3, episode 4) explores the love story of Kelly and Yorkie with gorgeous cinematography and compelling twists.

I am still deeply moved by the love story of the film The Bodyguard, with Whitney Houston, and the actors’ profoundly close relationship off-screen. The scene of her rendition of “I Will Always Love You” will never not take my breath away. Houston appears in the U.S. TV film adaptation of Cinderella as the fairy godmother—my favourite out of the 12 film adaptations in English of the fairytale. The two lovers had great chemistry, the script was refreshing, and Brandy was my first Black princess.

The South Korean period drama The Handmaiden, based on the novel Fingersmith by Sarah Waters, gives the lovers insanely high stakes. The final twist blew me away and cemented it as one of the most intriguing love stories I have ever seen. The groundbreaking Kenyan film Rafiki, written by Wanuri Kahiu (and adapted from “Jambula Tree”), is a love between women that is extremely rare in African cinema, and the characters—along with Kahiu—fought for their hopeful ending. It changed my life and I am endlessly grateful for them.

One of my favorite music albums of all time is Blonde, a heartbreaking masterpiece by Frank Ocean. I still carry the love stories and every lyric with me, every day. The song “Self-Control” embodies the ache of young, reckless, star-crossed love, in a way that leaves me speechless.

________

Troy Onyango is a writer and editor from Kisumu. He is the founder and editor-in-chief of Lolwe.

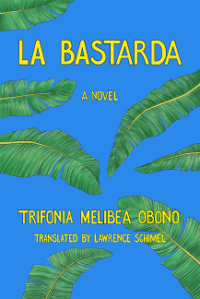

La Bastarda by Trifonia Melibea Obono is a coming-of-age story set in rural Equatorial Guinea, and it’s such a powerful portrayal of the kind of love that exists outside the margins of a patriarchal society. The love between Okomo and Dina is one that stays until the end, giving the novel an uplifting feel.

________

Chekwube Danladi is a writer of poetry and experimental fiction. Her work can be found at www.codanladi.com.

Notes of a Crocodile, by Qiu Miaojin, is a novel which explores the turbulent relationship between two women, Lazi and Shui Ling, in post-martial-law Taiwan. It is a love complicated by heteronormative cultural violence and lesbian erasure. I adore this book; it’s devastating, demanding, and stunning. Lazi and Shui Ling manage a hidden but potent love, one that is desperate to survive and to ensure mutual transformation between the two of them. It’s romantic, communal, and has the ghostly ties of familial love. It’s about the despair born from longing, and the pleasure fuelled by exploring sexualities liberated from oppressive social ideologies.

The love blooming between Lazi and Shui Ling is limitless beyond its silence, escaping the bounds of gender and class. Still, Miaojin’s writing makes sure to break your heart over and over again, to ensure that it is still capable of love. Do Lazi and Shiu Ling find a happy ending? It’s unclear. Yet, without doubt, theirs is a love that survives their ego deaths, sure to be reborn over and over again.

________

Umar Turaki’s debut novel Such a Beautiful Thing to Behold is forthcoming this year from Little A.

I’ve been listening to Sia’s “Soon We’ll Be Found” a lot lately, which is one of my favourite songs of hers. I love how it underscores the difficult but necessary work that goes into making triumphant relationships, be they romantic or otherwise.

The film Punch-Drunk Love by Paul Thomas Anderson centres a couple of eccentrics in this ode to a kind of goofy, strange, passionate, and deeply human love between misfits. Of course, I can’t pass up the opportunity to talk about a romantic film without giving a shout out to Jadesola Osiberu’s Isoken, a charming, wise, lovingly crafted celebration of a romance that dares to cross boundaries.

And then there is Atonement by Ian McEwan. That a tale so chilling in its depiction of war and the ruthless, lethal drudgery of time as it sweeps away all that is before it (including both fighters and lovers) took off simply because someone looked at a blossoming love affair through a fractured lens and deeply misunderstood it—what could be more heartbreaking than that!

________

Ukamaka Olisakwe is the author of Ogadinma, or Everything Will Be Alright (The Indigo Press, 2020) and the founder and editor of Isele Magazine.

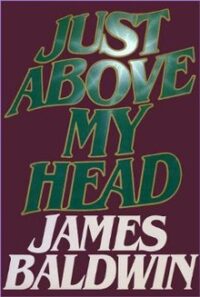

Love in James Baldwin.

As we follow his work to his late years, we see how, to him, love means community, and we see him dramatize this in Just Above My Head, in which he writes unapologetically about sex and the body in ways earlier American critics claimed detracted from “literariness.”

In Just Above My Head, this memory-driven narrative that sifts into different consciousnesses, we follow Hall Montana as he grieves and reconstructs his late brother Arthur’s life. Hall respects his brother’s sexuality and choices. Here is an openly supportive family at a time when homophobia was rife in their society; here is a heterosexual man describing his brother’s sex life as we have never seen before in Baldwin’s oeuvre. Hall adds personal commentary while narrating his brother’s intimate moments, like when Arthur and Crunch are about to make love and Hall freezes the frame to let us know that Arthur does not like to be naked in front of anyone. “Even me,” Hall tells us, “perhaps, especially me.”

Love in this novel is tender, shared, and communal. We witness this when everyone rallies around Julia after her father rapes her and after she loses her pregnancy. We see this love in Julia and Ruth’s genial relationship, despite the former’s sexual history with Ruth’s husband, Hall. We witness it in how Hall’s mother, Florence, cares about Julia’s sick mother, Amy. It takes a community to redeem people from themselves; it takes a community to rebuild what society has devastated.

Love in this novel is also shown in the simplest leisurely activity, like when Hall, Ruth, and their children gather at Julia’s home for a fun evening, and listen as she shares family stories using a photo album. Love in this novel means families and friends gathering to eat, to light each other’s cigarettes and favorite liquor, to cling to each other for support in difficult times.

________

Hauwa Shaffii Nuhu is a poet and a staff writer at HumAngle.

C-Kay’s “Love Nwantinti”—the remix with Kwame Eugene and Joeboy—is a song that touches the depths of my heart and makes me happy. It addresses love and desire in shameless fullness and vulnerability.

“My baby, my valentine. . . if you leave me, I go die, I swear. . . .,” it begins. “Your love dey totori me, I am so obsessed.”

It deviates from the old, boring way that Nigerian men sing about desire—as conquest, as power, and sometimes even threateningly, ha ha! They say, “I get big cassava/ I get big banana.” It is always about them. But what Ckay, Kwame Eugene, and Joeboy do here is to deconstruct that idea. They sing erotically but also centre the object of their love, and with language that is witty.

They sing, “Girl, I want to go but you got coming/ Call me Mr Bee(an), I go make you ho(r)n(e)y.”

They sing, “Girl, na you dey make my temperature dey rise. You’re like the oxygen I need to survive/ Come and make a bad man sing.”

They are only interested in the vulnerable parts of desire, how it softens you. It is a great love song.

________

TJ Benson is the author of two novels, The Madhouse (Masobe Books & Penguin Random House SA, 2021) and People Live Here (2022).

Ammu and Velutha’s love in Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things remains a touchstone for me. It is a reminder of the seeming inevitability of love, its transformative and transgressive powers, and its often overlooked relationship with and influence from the society. Ammu’s children, who would normally be the first hindrance to such an affair, are instead the first to fall in love with Velutha, before transporting her in her dreams to him. Even in a world where it is supposed to be impossible, love is still made real by almost mythic forces.

________

Emmanuel Esomnofu is a Nigerian writer and culture journalist. He’s a staff writer at Open Country Mag. Tweet him @esomnofu_e .

Love is one of life’s enduring lessons, so omnipresent, in fact, that sometimes we become unfeeling towards it. If not for creativity, there’s no telling what might become of us. I have encountered a number of works that moved me in profound ways.

One is Benjamin Cleary’s Swan Song, starring Mahershala Ali, one of my favorite actors. Like Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind before it, Swan Song is a stirring meditation on memory and loss, and the pains we go through in order to survive in love. Watching it, I thought: “Why is it love if it hurts us so? If it blows one open to anything, good or bad, why does the bad linger a lot longer?” Ultimately, it’s a film I’m grateful to have seen, only because it’s not a heady watch (as most films with technological leanings tend to be), and moves rather quickly.

Music provides me with crucial touchpoints for understanding contemporary manifestations of love. An album I’ve been listening to a lot is Saba’s Few Good Things, particularly because CARE FOR ME, his previous album, was written around the death of his beloved cousin and lined with effusive melancholy, soaring with tender grief and vivid stories of their time together. Few Good Things isn’t all cherry and positive, but Saba steps towards the light, towards the reality that he’s got life ahead, that he’s got memory, and that the dead, too, will forever live through him.

More love songs I have been listening to: Tems’ “Free Mind,” JP Cooper’s “Closer,” Fave’s “Baby Riddim,” The Lumineers’s “BRIGHTSIDE,” Tay Iwar’s “SIDELINES,” Fatoumata Diawara’s “Willie,” Miley Cyrus’s “Malibu,” Hozier’s “Jackie and Wilson,” Dwin, The Stoic and Rhaffy’s “Streets,” CKay’s “Felony,” Coldplay’s “Higher Power,” Bastille’s “Quarter Past Midnight,” M.I Abaga’s “You’re Like Melody, My Heart Skips a Beat,” and Mereba’s “Rider.” Most of these songs don’t centre a romantic interest, but they’re nevertheless strong records about being in love with oneself, making brave decisions that positively advances one’s mental wellbeing, regardless of what society conforms to.

I am looking right now at Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Purple Hibiscus—a hallmark of excellent storytelling from any part of the world. John Green’s The Fault in Our Stars is a love story that will forever stay with me. Any of the poems in Romeo Oriogun’s debut collection Sacrament of Bodies is always a riveting read.

J.M. Coetzee’s Slow Man is a slow, sad book, but it’s also wise and lyrical. Otosirieze Obi-Young’s “You Sing of a Longing” is one of the most brilliant short stories I’ve ever read, tussling with so much desire and heart, brimming with unforgettable scenes and characters, channelling our natural instincts to love and be loved.

________

Adams Adeosun is an MFA student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

Last August, I saw Painting With John, an art documentary by and about the artist John Lurie. In it, Lurie says, “I don’t know what the fuck I’m doing. I’m just stubborn. I just refuse to let these paintings be bad.” What I’m trying to say is that every story—whatever the medium or genre, whether or not its major preoccupation is love—is, first, a love story; for at the base of it all is a person enraptured by a form, filled with (romantic) notions of it, toiling away at the material despite a tragic awareness of the two-way limitation.

But Lurie’s show is not my favourite love story, it isn’t even my favourite art documentary. I favour a different art film, Celine Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire, about a painter and her subject whom she—in addition to the artist’s love of her form—has a more carnal love for. I love Portrait of a Lady on Fire most despite having recently read Anais Nin’s Henry and June and James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room, and seen Richard Linklater’s The Before Trilogy and Park Chan-wook’s The Handmaiden. I love it because it does something stories about love rarely do: it eschews the possibility of possession. Whether or not Heloise and Marianne will end up together is never the question or tension. The portrait that brings them together, mediates the way they see each other, and serves as the physical manifestation of their love is also the instrument of their separation. In its own way, the film occupies the more precious and volatile terrain of the memory of love, the story a gestalt of their nine-day affair.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire is a queer reinterpretation of the Ovidian legend of Orpheus and Eurydice. Somewhere around the middle of the film, when Orpheus’ infamous decision to damn Eurydice to Hades comes up, the lovers, perhaps recognising themselves in the dilemma, jostle for justifications. Marianne says, “He chooses the memory of her. . . He doesn’t make the lover’s choice but the poet’s.” Heloise says, “Perhaps she was the one who said, ‘Turn around.'” Even as they become more intimate, the lovers are requesting understanding of each other, making space for the end of their love.

This end is not a demise. It is a freeze frame transferred onto a canvas where it has a chance to outlast the painter and her subject, untainted by further tampering. It is a preservation in the museum of memory, a canonisation preventing their fire from becoming cinder. Like John Lurie, Marianne and Heloise refuse to let the portrait be bad, they refuse to let their love go sour. They don’t insist on possession.

I cannot decide if Portrait of a Lady on Fire is a sad or happy love story, but it is the best I’ve seen around.

________

Tamantha Hammerschlag is a lecturer at the University of KwaZulu Natal. She is presently completing a novel.

One of my favourite love stories is Maru by Bessie Head. In her introduction to the novel, Head states that many women readers wrote to her to say that they had fallen in love with the title character. As a teenager, I think I was partially in love with him myself.

Maru is a destructive patriarch, he deceives his best friend Moleka, he almost kidnaps the main character Margret Cadmore, whisking her away to live with him at her lowest and most vulnerable. Yet his love is redeeming, infinite, and all-encompassing. He loves her infinitely and completely and communicates with her on a soul level via dreams. And somehow that seems to make it all okay and worthwhile.

Maru calls Margret Cadmore “My sweetheart.” And we are told, “They were the most precious words if you knew the horror of what can pour out of a human heart.” And they are the remedy for the “wild jiggling dance and the rattling tin cans” of ostracism and disdain, being spat on and derided. Here, love is allegorical; it is the antidote to the poison of racism.

Love in Maru is complex, painful, vicious. There are so many types of love and love stories treaded in the narrative: the strangely cold and impersonal love between stepmother and child, the love between friends, between brother and sister, between individual and community.

Love in Maru is multifaceted and complicated; it is presented as a cure but not as an easy solution. In this strange allegorical novel, it is considerably preferable to lovelessness.

I have always loved the novel Maru, and re-reading it now as an older woman, I find I still do.

________

Adachioma Ezeano is a 2021 O. Henry Prize recipient. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Granta, McSweeney’s Quarterly, Guernica, FlashBack Fictions, Best Small Fictions 2020, and Best Short Stories 2021.

Love is self. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah gives this gift.

Once, I sent an email to an aunt, an email I now see as animatedly performative, heavily worded but saying nothing. Her response was a biting question about purpose. My email was one of those effects of vodka, spurs of the moment, or, more honestly put, the consequence of not knowing oneself—like greeting “Good Morning” because everyone says “Good Morning,” not because I knew what “Good Morning” meant. How can you give what you do not know? So much about living in this world is limping with societal expectations. At what point do we determine who we are, what we want—what we really, really want? At what point do we love ourselves to the point of choosing ourselves first? That is the love story. Self as the home, self as our own society.

In Americanah, the love of Ifemelu and Obinze, while still about frissons, melting insides, and soul-to-soul meet lips, is about the self. It is a journey of leaving home to find self, of returning home to accept self—being insistingly selfish for self-actualization. Love ventriloquizes self; it is a calm sincerity one shares with oneself; the consistency of tolerance, a drumful of grace and mercy acted towards oneself and others, the ability to set aside biases and flamboyant expectations while still placing self above all else.

Ifemelu doesn’t find herself with her American boyfriends. With Blaine, “there was cement in her soul.” With Curt, “she had longed to hold emotions in her hand that she never could.”

This is the consequence of choosing ourselves: we collect joy; we break the silences which do not let us breathe; we fill the gap with our echoes─echoes reminding us to move with intentionality. And to be defiant about it. It is only after this, only after we have doggedly decided to love ourselves first, can we return with clearer sights, return and build a perfect union with our own Ifemelus and Obinzes.

________

Uzoma Ihejirika is a Nigerian writer and a staff writer at Open Country Mag.

One evening, I happened upon the classic 1980 romantic drama Love Brewed. . . in the African Pot, by the veteran Ghanaian filmmaker Kwaw Ansah. The film, set in post-colonial Ghana, is about a young woman and a man united in love and separated by social class: Aba Appiah (Anima Misa) is the daughter of a thriving, middle-class businessman, while Joe Quansah (Reginald Tsiboe) is an auto mechanic and the son of a fisherman.

I was touched by the tenderness Aba and Joe shared. That tenderness, even when poked at by familial grievances as well as supernatural adversaries, remained intact to the end. I crave for that sort of affection: open, vulnerable, and yet sturdy in the face of overwhelming gloom.

One scene I particularly liked is when Joe returns home with a signboard meant to advertise Aba’s business. The signboard read: HOME OF MODEN FASHON CAPE COAST TRAiNeD. “Joe, you’re great, just great,” Aba says, smiling. “Who wrote it?”

“Very great, isn’t it?”

“I like the way you spelt modern and fashion.”

Joe laughs and says, “Yes. M-O-D-E-N.”

“There’s an R before the N.”

“Huh?” Joe laughs again. “Very great, isn’t it? That will bring plenty customer.”

In that moment, Aba doesn’t care too much about grammatical correctness; it is the intention behind Joe’s action that she sees and feels: he loves her.

Love, in word and in deed, is what I crave. Need. That has stayed with me.

(The film also inspired the title of my short story, “A Taste of Love Dipped in Hot Sauce.”)

________

Olakunle Ologunro wrote the short story “Our Girl, Bimpe.” He is a finalist for the 2020 Adina Talve-Goodman Fellowship from One Story Magazine.

“Birdsong” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is the story of an affair between a young woman and a married man whose wife and children are in America. Theirs is the kind of love everyone warns you about: love for someone that doesn’t belong to you, love for someone who cannot love you the way you want them to.

“I was swamped with emotions that I could not name for a man I knew was wrong for me,” the narrator shares to us.

“Have fun oh, as long as your spirit accepts it, but as for me, I cannot spread my legs for a married man,” her colleague tells her.

Yet she moves into his place and stays for 13 months and eight days. She allows herself to imagine a future with him. Because that’s the thing with love: it defies all logic and reasoning. When it happens to you, you simply let it.

Which is why, when her lover betrays her with his wife, I felt torn. On the one hand, I knew it was a love story that may—will—not end well; on the other hand, I wondered who I would apportion the larger blame to: the lover for betraying the trust they share in the affair, or the narrator for choosing to love what was never hers to love? Again, it is love: it defies logic and reasoning.

For a long time after I read this story, I was left with an intense desire to have an affair, be entangled with someone who could not be mine, who was never mine. No, it wasn’t because I wanted to love them into choosing me and loving me back, it was because I wanted to be hurt by them. I wanted to feel, personally, the kind of hurt the narrator felt after her lover betrayed her trust. That kind of hurt that would feel “as though bits of my skin had warped and cracked and peeled off, leaving patches of raw flesh so agonizingly painful I did not know what to do.”

This, I think, is what a properly told love story looks like: it makes you empathise with the character so much, you want to go out and love recklessly, knowing that you could be hurt, but choosing to love regardless.

________

Dr. Innocent Immaculate Acan is a writer and medical doctor. She won the Writivism Short Story Prize in 2016, and is in love with the idea of love.

I’ve been an avid consumer of romantic art—mainly film and literature—since I was a little girl on the cusp of adolescence. I also grew up staunchly Catholic but became quite worldly, so it comes as no surprise that, for me, the question of romantic love brings to mind two works of art that circle Catholicism: the comedy-drama Fleabag, written by Phoebe Waller-Bridge, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s debut novel Purple Hibiscus. They both feature romance (speculative or definitive) between a priest and a layperson.

I find Fleabag particularly titillating. I suppose, for me, it’s the cheeky thought that one could dare to go up against God and win. What kind of love could be more potent, more exhilarating? Perhaps that says something of my deepest thoughts on romantic love.

Often, when we find a significant other, we demand that they put us first, above all else. At the very least, we yearn for it. How then do we place a thing that makes us the most selfish versions of ourselves on such a high pedestal? What does it say about us? Are we innately selfish creatures, seeking our own satisfaction first even in the one instance where selflessness should be the ideal? Or maybe, we are simply the truest reflection of the God who made us, selfish with the love of those we deem ours, till the very end.

________

Tobi Eyinade is the co-founder of Rovingheights and founder of The BookLady NG. She was shortlisted for The Future Awards Africa Prize for Literature in 2020.

I am a dreamy, hopeless romantic, and my ideal love is fueled by time and friendship. I remember reading Bolu Babalola’s Love in Colour one weekend, on a flight in and out of Abuja. I was spending time with a lover, now turned ex. It was one of the best moments of my life. I was in a happy, long distance relationship (or so I thought), and the last story in the collection, “Alagomeji,” remains unforgettable. I am enamored by how Prince and Princess’ love thrived on mystic letters, traversing oceans and postage stamps to keep their hearts aflame with fondness.

“Alagomeji” uses fluid metaphors that allowed me to recreate familiar places like Abeokuta and Yaba in my mind. I love the sheer show-off of the romantic nuances of Yoruba. This is a story I think I will enjoy sharing with my kids someday (if their Gen Alpha selves would listen).

In what I believe is a retelling of the author’s parents love story, the story leaves me with a must-have in my future romantic relationships: he must “understand laughter as a language and friendship as an active ingredient in true romance.”

________

II. Love, in Life

________

Logan February (they/he) is a nonbinary Nigerian poet, and the author of In the Nude (Ouida Poetry, 2019). They are an MFA candidate in poetry at Purdue University.

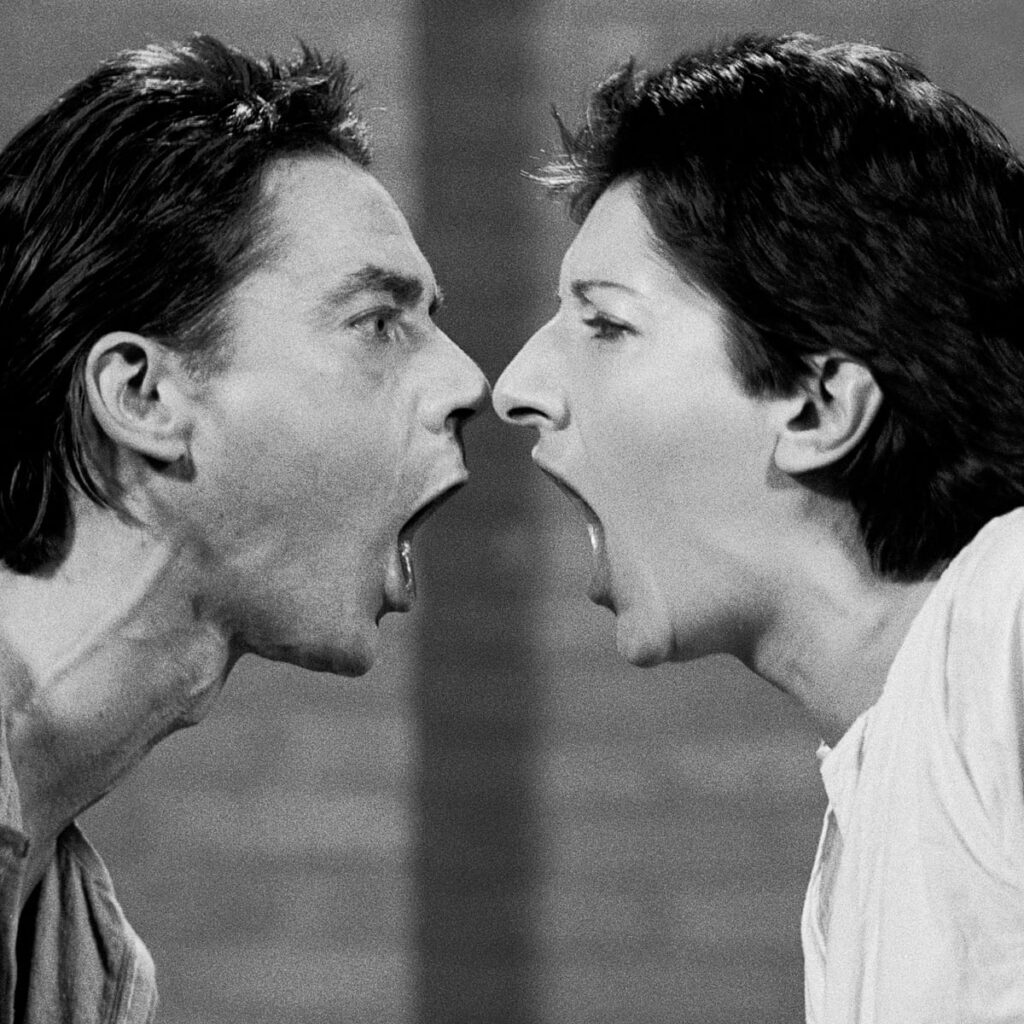

A love story I often think about is one drawn from the history of performance art, so it challenges certain notions of the materiality of art and the reality of romance. For 12 years (1976-1988) Marina Abramović and Frank Uwe Laysiepen (Ulay) were together as partners in life, love, and art. Born on the same day, November 30, they identified each other as soulmates, and spent their time together making an extensive body of work that explored dualistic themes of gender relations, power dynamics, and mysticism. They had a consciously poor and nomadic life together, living for three years in a small Citroën truck with their dog, Alba. They talked to each other in dreams, meditated and fasted together, and referred to each other as “Glue,” or a third, androgynous entity known as “That Self.”

After their early performances together, which were often risky explorations of physical limits demanding complete trust and reliance on each other, Marina and Ulay progressed to working on pieces that explored the limits of the mind. Here was the beginning of the end for their collaboration, when the works became structured more around long durations of stillness than physical endurance. For the first time ever, one artist could continue a performance after the other had stopped. Soon enough, their sacred symmetry was lost.

The artists’ final performance, “The Lovers,” was an epic farewell which saw them walk from opposite ends of The Great Wall of China for three months, to meet each other in the middle. Key themes in their work—walls, boundaries, lines of mystical energy, and the journey one body makes to meet another—found their peak in this iconic performance piece. Although the original idea had been for them to get married once they met in the middle of the Wall, the project had taken very long and their relationship had deteriorated by the time of its completion. The artists instead embraced each other, said goodbye, and went their separate ways forever.

The story of Marina and Ulay is something I’ve researched, largely for my own interest, for the past year. I’m quite fascinated by the progression from their intense identification and closeness, to a deep misunderstanding, alienation, and even hatred. In their work, the artists represented themselves as symbols of partnership, symbiosis, elemental balance. For me, the end of their love and partnership symbolizes the ageless problem of what it means to truly and fully understand someone else, or even oneself, and what it means if this understanding is sure to have its own limits.

________

Sandisile Tshuma is a multi-local, multipotentialite currently living in Dakar with the love of her life.

What a rush it was, that love. A burning comet streaking through the black sky of your woozy heart, that you thought would never be extinguished. You thought it would burn forever. But it didn’t. You were too much and yet never enough. You were all at once the thing that was wanted and the thing that was feared. You were yeses and nos. You tried too hard or maybe too little. Your love was not returned. Or it was taken, sucked dry and spat out, unsavored. Traded in for someone else. Someone better, less intense, more settled in their skin, more sure of their worth, offering lightness and certainty, all the good things with so much less effort. And so your love came to naught. All that passion, all that promise. Poems scribbled together on moonlit nights, breathtaking sunrises over the Indian Ocean, warm bodies entwined through bitter winters, morning commutes, champagne kisses, nerdy gifts, a musical score of low fidelity jazz. Wasted, wasted. Worthless hours of love.

But Chico Buarque doesn’t think so. In “Futuros Amantes” (“Future Lovers”), he sings that it’s alright because nothing is for now. Your love’s reward lies in the days to come. Take your heart, beaten and broken. Take your love, wild and raw. Express it, dance it, sing it, write it. Give it form. After all, love is a giving of ourselves to others. Yours will find its purpose in the hands and the hearts of lovers you will never meet. It will inspire and it will make its impact in civilisations yet to come. Here is the translation I love the most:

Don’t rush, don’t.

It doesn’t have to be right now,

Love has no hurry,

It can wait in silence,

At the bottom of the cabinet,

In the chest,

Millennia, millennia,

On air.

And who knows, maybe then

Rio will be

Some city submerged at the bottom of the sea,

The divers will

Explore your home,

Your room, your things,

Your soul, your hiding places.

Wise men in vain

Will try to decipher

The echo of words,

Fragments of letters, poems,

Lies, pictures,

Traces of a strange civilisation.

Don’t rush, don’t,

Nothing is for right now,

Lovers will always be kind.

Future lovers, perhaps,

will love one another without knowing;

They are using the love that one day

I had saved for you.

I discovered these words more than 25 years ago and was enthralled. I thought it was a poem and, soon after, found out it was a song. Did I dare to listen to it? No. Not then and not now. It is already beautiful. It already means so much. What do I care how it sounds? I find the track on YouTube and my cursor hovers over the play button. But I don’t press Play. Not today. Because not everything is for right now. So I save it for another day, another me, a future lover.

________

Adedayo Agarau is the author of the poetry chapbook The Origin of Name (APBF, 2019) and editor-in-chief of Agbowo Magazine. He is an MFA student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

Redemption. In “Can I Be Him,” James Arthur pleads. In “Mercy,” Shawn Mendes cries. I want to believe that we are all lost, godless souls consistently seeking redemption.

When my father and mother had a fallout the year we almost ran out of money, our house had dark clouds over it. It was terrible. We drank garri in the afternoon and ate eba at night. We skipped lunch to save food for dinner. We were in debt and were also being owed. My dad sold our cars and landed properties. I understand delinquency, the power that drives it, the spirit it steers across the station of a grieving body. I know that home is no longer your place if you feel inadequate in it. I watched my father drink, stay out late, seeking the slightest opportunity to enjoy himself.

We all believed the fallout was a spiritual attack. I mean, of course, it had to be. I joined the church’s prayer group. I prayed my knees red, prayed my throat dry, my voice away. I fasted for 12 days, breaking with water and fruits. I dreamt that a strange woman held me down in my sleep, and when I attempted to shout “Jesus,” she seized my voice.

One Sunday, my father followed us to church. As I prayed vigorously after service, for God to continue to order his steps back to his house, he stood beside me, watching with disgust. Then he sold a few more things and left for the U.K.

The arguments between my parents didn’t stop, despite the love they attempted to build over storms of cities apart. Their chaos made me think of Imagine Dragon’s “Radioactive.” As humans, we do terrible, unimaginable things at the break of dusk. The dark is an eerie place, it and the shadows have teeth.

Redemption is for the lost, the prodigal, the hopeless. But being lost is a state, a place, a city. And so is redemption. I think of Game of Thrones, when Theon Greyjoy’s torture by Ramsay Bolton forces him to find the essence of family, to rediscover the comfort of home. I cried when he loses his life to protect Bran at the Battle of Winterfell. I cried. I do not care about Theon Greyjoy, to be honest, but I find grace in rediscovery. How my father, slowly, walked himself back into our lives. He never left, but he wasn’t home. And my mom? ♦