Central to every good film are its writing, acting, and directing: the bases upon which others elements — editing, cinematography, sound, production design, makeup — either build or organize around. But in the very best films, every department must operate at a level so high, that they become as visible, as indispensable, as the big three. Our peculiar problem, in Nigerian productions, is that the big three components are so often afflicted by deficiencies in craft and technique, that only a few films manage to sail through uncompromised. For all its production problems, “Old Nollywood,” from the 1990s to the 2000s, was undeniable in its acting talent and, one might argue, a relentless vision of immersive storytelling. The result: stories that haunt now as they did then, even as they lack finesse.

Barring a few standouts, “New Nollywood” has not particularly excelled in any of the aforementioned areas; instead, the copout argument elevates cinematography, an indispensable but in-production art, as an imagined supplement for uninspired screenplays, performances, and creative visions. Still, some films float: Chineze Anyaene’s Ije: The Journey, Mildred Okwo’s The Meeting, Kenneth Gyang’s Confusion Na Wa, Kunle Afolayan’s October 1, Dare Olaitan’s Ojukokoro, Kemi Adetiba’s King of Boys, Genevieve Nnaji’s Lionheart, Ramsey Nouah’s Living in Bondage: Breaking Free, Chuko and Arie Esiri’s Eyimofe, and, perhaps the finest of the 2010s, Izu Ojukwu’s ’76.

Our inaugural list of “The 10 Best Films and TV Series of the Year” — a counterpart to our “The 10 Best Acting Performances of the Year” — prioritizes not the sparkle of ambition but the realization of narrative: in other words, efficiency: the ability of the story to take us from beginning to end, to cohere onscreen. Some of the films remake known concepts, infusing them with energy or localizing them. But many of them share one thing in common: in order to work, they required the performances to lead the way.

Our list considered only films I have seen, either on streaming or via screeners.

Honourable Mentions

No film dominated headlines last year like The Black Book, debut director Editi Effiong’s thriller about a hit man seeking vengeance: it scaled Netflix charts and found an audience in South Korea, a country whose films happen to have an audience in Nigeria. But it is C.J. Obasi’s Mami Wata that, in many ways, was the film of the year: the first Nigerian feature to premiere at Sundance and the country’s eventual submission to the Academy Awards — but it does not make this list only because I could not catch it in theatres and did not receive a screener.

One of my favourites is another debut feature and Netflix No. 1 hit, Ebuka Njoku’s Yahoo+, which, with haunting clarity, turns a hard gaze on a desperate side of Internet fraud. And despite its Season 4 dip, The Men’s Club’s chronicle of male friendship is still an interesting look at a certain Nigerian attitude to success.

10.

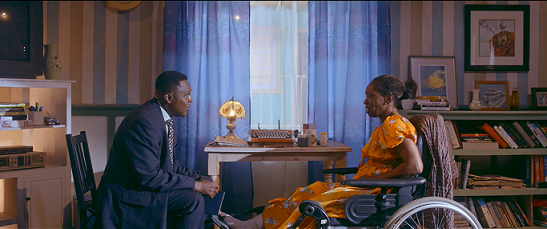

Sista, Stephen Biodun

In two timelines almost two decades apart, one woman, Sista (Kehinde Bankole), works to provide for her family. As a girl pregnant for her boyfriend, she is forced into living with him and raising their child. She is the one who bears the brunt of the responsibility, and, as the children get older, she still does. When said ex-boyfriend Fola (Deyemi Okanlawon), one of the most selfish men you’d see, returns to her life, seeking to reconnect with their children, there is a scene that unburdens the feminine travail at the centre of the plot. “So you are our dad?” the children ask Fola. “Father,” their mother corrects them: “There is a difference between the two. I am your dad.”

The success of Stephen Biodun’s feel-good screenplay is down to its simplicity, in how it burrows straight for the heart. It humanizes, with agency, what would have been a stereotypical working woman. Some of the characters would have felt like clichés in a different film, but here they work, illuminating the many indignities of class divisions. Despite minor inconsistencies in Biyi Toluwalase’s editing and Biodun’s direction, and the anachronism of a young working class couple owning cell phones in the early 2000s — when cell phones arrived the country in 2001 — Sista is a kind of film, pared down to the human elements, that Nollywood has always exceled in.

There are many actresses who could have done Vicky — a simple woman, a believer in honesty, and a protector of the life she has singlehandedly created for her children — justice. It is difficult, though, to imagine anyone else imbuing her with the startling detail and believability that Kehinde Bankole generously does. She carries the story, holding it together where the script falters for nuance, and placed at No. 3 in Open Country Mag’s “The 10 Best Acting Performances of the Year,” and at No. 2 in What Kept Me Up’s critics’ poll of the best film performances.

9.

The House of Secrets, Niyi Akinmolayan

A woman watches a couple from her window, writing a fictionalized version of their lives, and when she herself is hit by a bout of anxiety, we learn that she is secluded in an apartment, and that the people around her are NGO workers waiting for her to remember a political secret. There are several elements at work in Niyi Akinmolayan’s ambitious noir. It is an investigative story that reveals itself to also be a love story; it is set in a democratic present tethered to a military past. The two timelines alternate, and the latter, lit in black-and-white, is, in style and coherence, the more interesting one. The cinematography team of Ebitorufa Brisibe, Barnarbas Emordi, and Mbuotidem Uwah produce winning shots: the car scene of lovers, the balcony scene, the train scene.

The trio of Najita Dede as the woman regaining her memory, Charles Fuqua as her intense military man lover in her youth, and Kate Henshaw Nuttal as a government worker earned honourable mentions in Open Country Mag’s “The 10 Best Acting Performances of the Year.” The military-era storyline works due to the chemistry between Fuqua and Efe Irele.

The House of Secrets is decidedly Hollywood in its tone, but unlike the most recent notable film noir, La Femme Anjola, I am unsure that it succeeds in Africanizing it. Does it have to, though? Although Akinmolayan and Dolapo Adigun’s screenplay has heavy-handed dialogue and a plot without seamless transitions, relying too much on the audience to fill in information, it still feels like a statement of ambition.

8.

4:4:44, Izu Ojukwu

In a country of historically fascinating people, the biopic is a genre with great potential, and Izu Ojukwu’s decision to centre this one not on a famous figure but on regular citizen is refreshing. Alternating between 1943, when a couple meet, and 1960, a crucial point in their relationship, 4:4:44 is both a portrait of a romance and a mood board, a canvas on which a growing public issue, corruption, is crossed with a deepening private one: mental illness. Hilary and Theresa are played by Richard Mofe-Damijo and Nse Ikpe-Etim in the present, and by Seun Akindele and Efe Irele in the past. The four easily convince us that they are in love.

While Ufuoma Metitiri’s screenplay does not allow a complex view of Theresa by showing more of her without her affliction, and the voiceover could be more inspired, the framing of the film remains steady, and Pat Nebo’s production design keeps us grounded. Ikpe-Etim, whose performance here brought her the Africa Movie Academy Award for Best Actress in a Leading Role, finds ways to give what could have been a one-note character some variety in her outbursts. But it is Mofe-Damijo, as the husband going against his friends and community, that holds it all together. Ojukwu’s choice to end with a meta scene, set in real life, gives the story more weight.

7.

Shanty Town, Dimeji Ajibola

Shanty Town is a story of crime, community, freedom, and punishment that is tightly plotted and well-acted by enough of the cast that, despite narrative gaps, it rises to the top shelf of Netflix’s Nollywood offerings. Director Dimeji Ajibola, working with a screenplay by Xavier Ighorodje and Donald Tombia, realizes a sense of the epic, particularly in the first episode. The titular community is introduced in eloquent scenes of lived-in realism. It is engrossing world-building, perhaps the most maximized opening 12 minutes of any Nigerian TV series. Yet it is difficult to appreciate this without a caveat: there is a moral code around the onscreen depiction of violence, a code that protects the innocence of society’s most powerless, and that code is not extended to the little girl murdered in the first two minutes of the story, nor to the woman whose sadistic rape is indulged for the full glare of the viewer. (The voyeuristic indulgence cheapens what should have been presented as the violation of humanity that it is.)

Ultimately, the story of crime and punishment that Shanty Town tells is not a new one, but it is made fresh by, above all, the performances. Scar is a character realized with immediate detail and terrifying power by Chidi Mokeme, who turns him into one of the great villains of Nigerian cinema. The story is about Scar’s conflicts, including with his community of women and his person. But it would not work if Nse Ikpe-Etim as the resolute Enewan, Nancy Isime as the unrelenting Shalewa, and Mercy Eke as the spirited Jackie do not enhance what, on paper, would be stock characters we have seen before in Nollywood. The sisterly, cat-and-mouse dynamic between Ini Edo’s Inem and Ikpe-Etim’s Enewan gives the story breadth, and their first meeting, a conversation conducted almost entirely in Ibibio, is freeing and realistic — proof that we need more onscreen conversations in local languages beyond the major ones: Igbo, Hausa, Yoruba.

The gritty realism of Shanty Town goes for extremes, but the show’s best asset is its characters. That is why Mokeme is No. 1 on Open Country Mag’s “The 10 Best Acting Performances of the Year,” and Ikpe-Etim is No. 4, and Isime gets an honourable mention.

Read our review of the series.

6.

Ijogbon, Kunle Afolayan

In a sleepy, hilly Yoruba town, four teenagers discover diamonds in the forest, and, in taking us through the resultant disaster, Kunle Afolayan crafts a tense story of friendship, dreams, danger, and fate. Sweaty in their school uniforms, the teenagers climb hills and imagine life beyond their small world. “Are you not tired of this place?” one asks the rest. They imagine leaving to seek excitement; but what they could not imagine: that an unwanted thrill — in the shape of criminals who claim the precious stones — could come to them instead.

What guides Ijogbon is a sense of impending doom, but also, courtesy of Tunde Babalola’s focused script, the question of how much of life demands that we seize chances, and at what cost. Yet these alone do not account for the unity of place and plot that the film achieves: that comes from the rooted effect of Adekunle Adejuyigbe’s cinematography — impressive from the first frames of miners at work and those of the children on the hill — and its alignment with the sound design by Owen Busari-Okoro and Yemi Joseph Ogunmoroti.

For all its thrills, this is a film that required characterization to succeed, and its young ensemble — Kayode Ojuolape, Ebiesuwa Oluseyi, Ruby Akubueze, and Fawaz Aina — manages, each to varying degrees, to convey not only the thrill and pain of sudden luck and fracturing but also the awareness that there is another way that life could have turned out for them. It earned them a collective honourable mention in Open Country Mag’s “The 10 Best Acting Performances of the Year.”

5.

All Na Vibes, Taiwo Egunjobi

From the very first shot, I was hooked by Taiwo Egunjobi’s neorealist story about three students during an ASUU strike. It is unvarnished, the frames move one after another, without style but with mounting intention. See how the basketball scene plays out, the awareness of the young men not only of who each of them are but of what their country is doing to them, denying them education: see the shot of the seating arrangement on the stadium. It is one of a few scenes that nail the soul of a generation seething. It is a slice of our life.

For flow, the film relies on the chill-vs-extrovert energy of its leads, Tega Ethan’s Abiola and Molawa Davis’ Lamidi. Their friendship breathes and complicates in the way that friendships between young people tend to do, yet one does not know the other as much as they might think. Ours is a dream-stricken generation, and the countless ways that Nigeria can eviscerate dreams come together here, devastatingly. It is my favourite film of the year, because Ethan, who placed at No. 8 in our list of best performances, plays a character I know in my own life.

4.

Battle on Buka Street, Tobi Makinde & Funke Akindele

In this refreshing, probing melodrama, two half sisters inherit their mothers’ rivalry as co-wives, and take it further. Yet Battle on Buka Street is so much more than a story of competing wives, mothers, and chefs: it is an exploration of envy, ambition, and the dynamics of hurt; a contemplation of dreams; and how these shards are deposited on the shores of new generations. The lead roles of Yejide and Awele are handled by Funke Akindele and Mercy Johnson, respectively (the latter is No. 5 in our best performances list, and the former earns an honourable mention). The younger Asake (Yejide’s mother) is, briefly, played by Bimbo Ademoye, and the older one, with whom we stay for most of the film, by Sola Sobowale. Ditto Ezinne (Awele’s mother): first by Perpetua Ukadike, and then by Tina Mba.

The film has remarkable, enlivening breadth — a rare quality in Nollywood — and owes its success to the script by the quartet of Jack’enneth Opukeme, Stephen Oluboyo, Jemine Edukugbe, and star Funke Akindele, who gets a credit. Their script, taking up challenges, goes deeper into the layers of conflict. It is not merely mother and daughter vs. mother and daughter; we begin to see mother vs. daughter in each household, and even grandmother vs. mother vs. daughter. This is a story of ordinary people living interesting lives and taking fate into their hands. Through its plotting in mini arcs, the script works overtime, pacing events, knitting developments, folding back stories into tight dialogue, and keeping the plot moving. The result is a narrative that, although filled with detail, is also compressed, which lets its emotions simmer. It is an indictment of the AMVCAs that one of the best realized films out of Nollywood lost both Best Film and Best Writing to a movie it is much, much better than.

Battle on Buka Street established Akindele as Nollywood’s most attuned producer and broke her own record for the highest grossing Nollywood film of all time, with N668 million, besting her previous effort, 2020’s Omo Ghetto: The Saga’s N636 million. (She has since broken the record again with A Tribe Called Judah, which became the first Nigerian film to gross over N1 billion.)

3.

Gangs of Lagos, Jade Osiberu

In depicting gang life in bustling Lagos, Jade Osiberu tells an epic story of the hold of legacy and history, and the seeming inevitability of a young man falling into their grasp — a framing repurposed from Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York. She is careful not to render Isale Eko in simplistic terms: crime is potent and people suffer beneath power tussles, but it is also a complex community that turns to the Eleniyan to save their kidnapped children or retrieve stolen bags, a place that prizes family and loyalty. A sure-footed story emerges from this warring dichotomy, although a lot of its themes, of ambition, power, corruption, are crammed by Osiberu and co-writer Kay I. Jegede into commentary and underwhelming dialogue.

This is Prime Video’s first Africa Original, and it is often shot with style by Muyiwa Oyedele, so that the fight scenes are an improvement from the typical cartoonish stuff from Nollywood. Some stand out, like Obalola’s in the warehouse, and others, like the final clash, are clunkily choreographed. The street brawls really lean into the macabre, an echo of the violence that pervades Nigeria in reality. The cast turns in solid performances. Three of them — Tobi Bakre as the pensive but resigned older Obalola, Chike bringing levity as the hopeful musician Ifeanyi, and Chioma Akpotha as Ifeanyi’s quintessential Igbo mother who delivers a striking monologue — made Open Country Mag’s list of “The 10 Best Acting Performances of the Year,” and two more — Olarotimi Fakunle as the cruel Kazeem and Iyabo Ojo as Obalola’s morally punishing mother — earned honourable mentions.

2.

The Trade, Jade Osiberu

When we meet Eric in the first scene of The Trade, his stony eyes are those of a man scarcely saddled by his conscience. Still, Jade Osiberu’s direction humanizes this serial kidnapper, not in a sympathetic light — like a lesser, misguided film might — but as a man unwittingly shackled by a sense of responsibility. But The Trade is unconcerned with probing how patriarchal values could pervert a man into a life of crime — which would have been its own riveting story — so it instead follows the police in pursuit of the notoriously elusive kingpin.

The film casts a frank, modest portrayal of the Nigerian police that is, curiously, rare. It thrives the most when it leans into its thrill, and while it boasts a steady plot, it feels held together more by Chuka Ejorh’s editing. Blossom Chukwujekwu’s indelible lead performance as Eric landed him at No. 2 on Open Country Mag’s list of “The 10 Best Acting Performances of the Year.” But some of the cast deliver as well, including Shawn Faqua as an overenthusiastic recruit and Stan Nze as Eric’s aggressive new worker. And there is major star Rita Dominic in a small supporting role.

1.

Jagun Jagun, Adebayo Tijani & Tope Adebayo

The first time we meet Gbotija (Lateef Adedimeji), he is in the forest, and when a baobab tree falls, blocking his path, he commands it to rise, and it does. That power to commune with wood will platform his rise as he attends the Academy of Warriors, and save his life a few more times when Ogundiji (Femi Adebayo), the ferocious warlord who presides over the school, deems him a threat and puts him through four potentially fatal tests.

Adebayo Tijani and Tope Adebayo satisfactorily deliver a story of ambitious scale that, familiar as it is, succeeds in almost every way. It is a story of rivalry and of love, an enthralling portrayal of ancient wartime Yorubaland that, from electrifying war scenes to fully formed characters, moves with energy, and also a depiction of power dynamics and class warfare infused with tension by screenwriter Tijani.

Lateef Adedimeji gives Gbotija a resonance, Femi Adebayo is impressive, and Ibrahim Yekini’s solid, conscious Gbogunmi is a foil for both men. (The trio earned honourable mentions in Open Country Mag‘s “The 10 Best Acting Performances of the Year.”) The special effects by Hakeem Onilogbo surpass anything we have seen from Nollywood so far, especially in its details: the mesmerizing sparks of sorcery and the haunting presence of the spirit Agemo, for example. The score by Tolu Obanro, and soundtrack by Adam Songbird, intensifies the drama, harmonizes with Adeoluwa Owu’s cinematography, and propels a world where magic and myth coagulate, and a story that elevates the Nigerian historical fantasy epic.

Read our review of the film. ♦

Paula Willie-Okafor and Orji Victor Ebubechukwu contributed to this feature via previously published reviews.

To send us screeners for our 2024 list, please email editors@opencountrymag.com.

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

No One Covers Nollywood Like Open Country Mag

— The 10 Best Acting Performances of the Year

— Rita Dominic‘s Visions of Character

— The Epic, Transformative Comeback of Chidi Mokeme

— How Mami Wata Swam to Sundance

— How Dakore Egbuson and Tony Okungbowa Traverse Trauma in YE!

— Writing Omo Ghetto: The Saga, Nollywood’s Highest Grossing Film of All-Time

— How Yahoo+ Captured a Desperate Side of Internet Fraud

— Awaiting Trial: Families of SARS Victims Speak in Devastating Documentary

— Country Love Depicts Tenderness in LGBTQ Lives

Or African Literature

— Cover Story, December 2023: How Leila Aboulela Reclaimed the Heroines of Sudan

— Cover Story, September 2021: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is in a Different Place Now

— Cover Story, July 2021: How Teju Cole Opened a New Path in African Literature

— Cover Story, January 2021: With Novels & Images, Maaza Mengiste Is Reframing Ethiopian History

— Cover Story, December 2020: How Tsitsi Dangarembga, with Her Trilogy of Zimbabwe, Overcame

— Cover Story, April 2022: The Next Generation of African Literature

— Cover Story, February 2022: The Methods of Damon Galgut