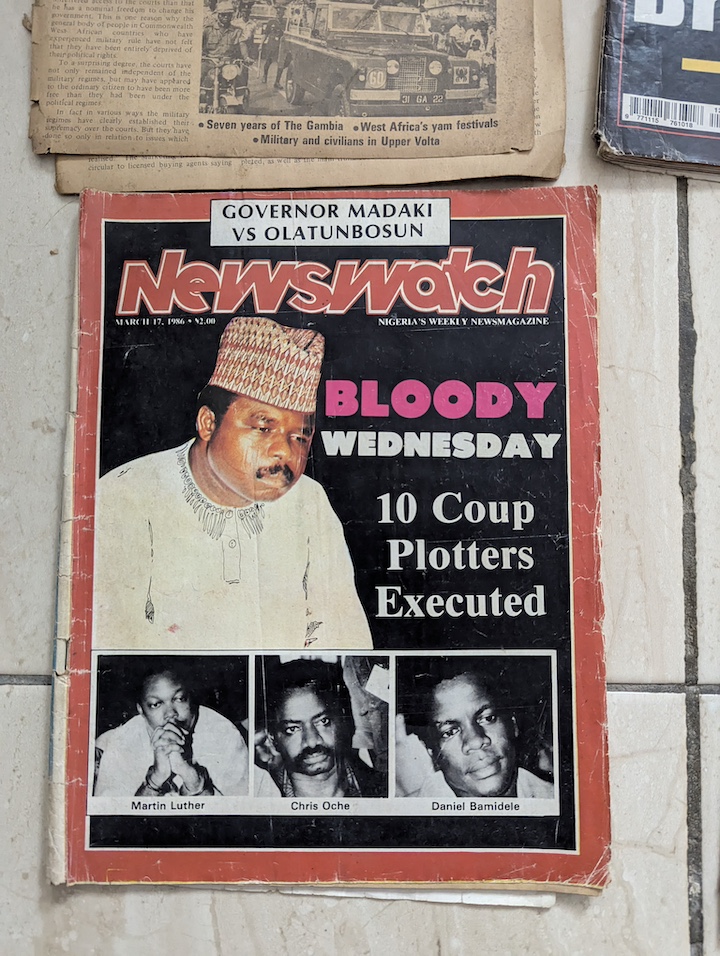

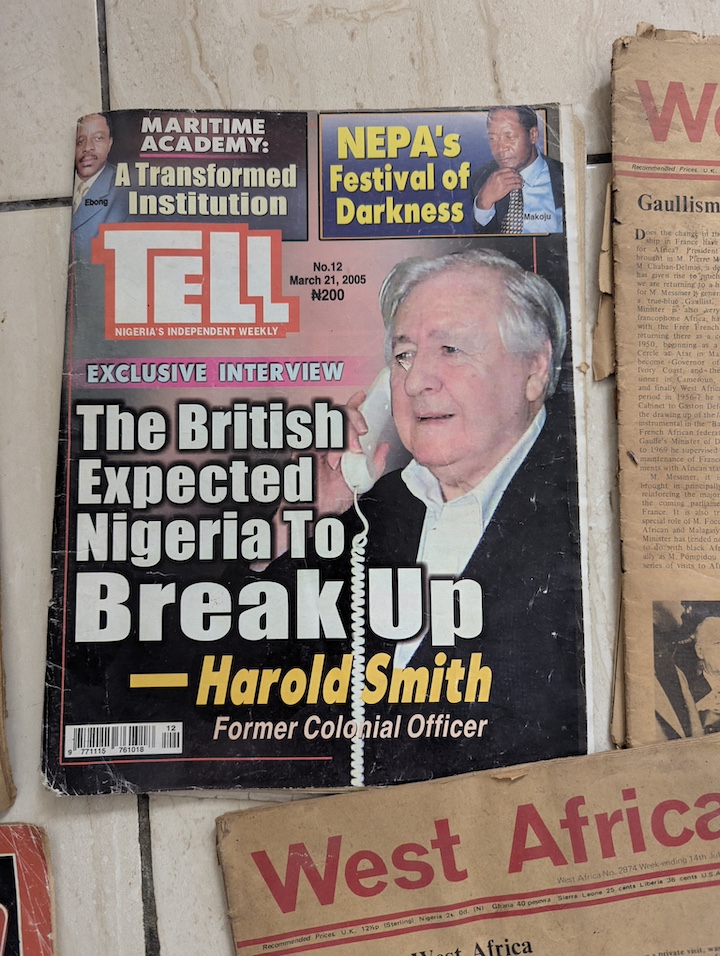

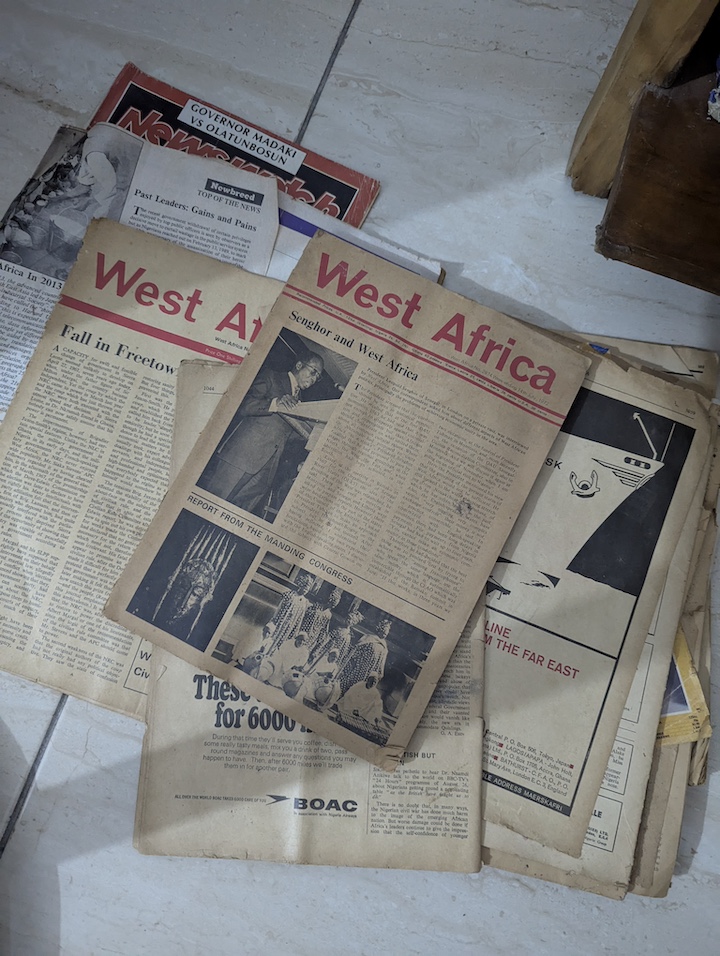

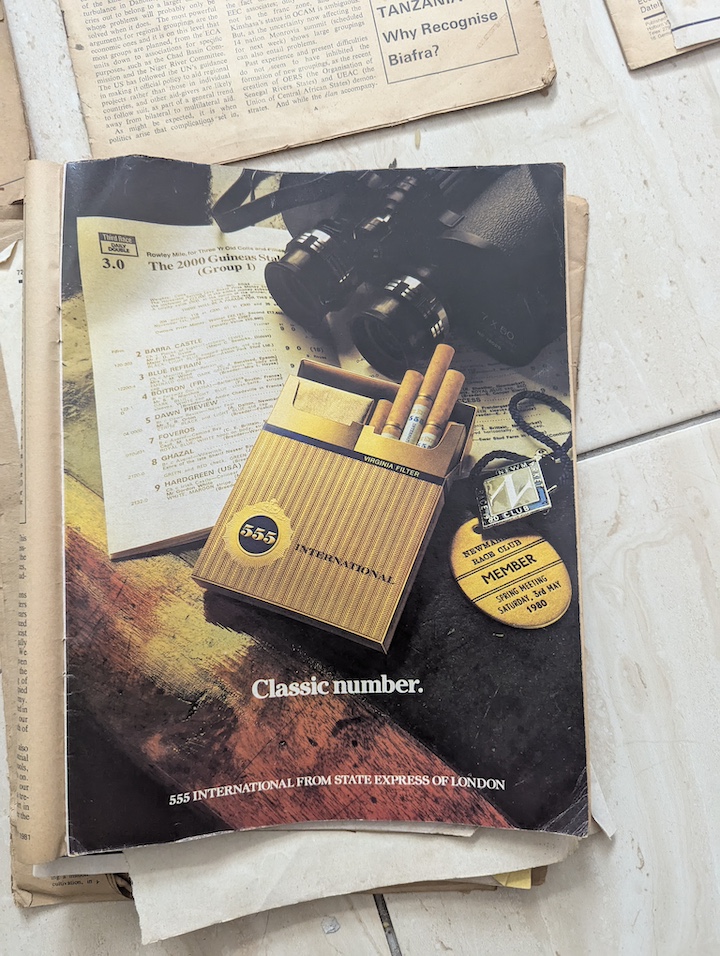

When Taiwo Egunjobi first began to sketch the emotional and visual palettes of A Green Fever, his historical mystery set during military rule, he sought inspiration in his father’s old magazines. He knew he didn’t want spectacle. He wanted mood, he wanted texture. There was an unease in that era and he wanted it to bleed into the story. He shows me pictures of print archives of Newswatch, Tell, and West Africa: a full-bodied time capsule of the Nigeria of the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s. One magazine is themed Africa, with articles announcing: “Obote Secondcoming,” “Senghor Bows Out.” Another samples IKB beauty products. “They had the most beautiful advertisements,” he says, recounting to me glossy beer and cigar ads, the bold colours of the beverages, the effortless elegance of well-dressed men and glamorous women smiling out of vintage spreads. For a long time, those ads were the most exciting part of his reading. But as he grew older, he began to dwell on the stories. The letters to editors. The musings of citizens. The political intrigues of military men angling for power.

The research process was extensive, not because of imposed complexity but because he was, as always, chasing authenticity. He needed to achieve the cloistered, tense atmosphere of the ’80s, the grainy feel of an period he hadn’t lived but somehow carried. He looked at the literature and cinema set in that decade. He read a novel by Chris Abani that he can’t quite name now but remembers for its “sordid” honesty. He watched Izu Ojukwu’s ‘76, parsed design references from Kunle Afolayan’s Swallow, and explored YouTube for Ade Love trailers.

Taiwo Egunjobi’s research for A Green Fever included 1980s newspapers and magazines.

Taiwo Egunjobi’s research for A Green Fever included 1980s newspapers and magazines.

Taiwo Egunjobi’s research for A Green Fever included 1980s newspapers and magazines.

Taiwo Egunjobi’s research for A Green Fever included 1980s newspapers and magazines.

Egunjobi cast his primary actors with intent. He wrote the lead role of Kunmi Braithwaite for Temilolu Fosudo, his long-time friend since their University of Ibadan days, someone who “could handle lots of dialogue in a tight space.” He had seen William Benson Chinoyenem in Herbert Macaulay and was intrigued by his presence, his theatre roots, his charisma, and offered him the antagonist role of Colonel Bashiru. He wanted Ruby Precious Okezie as the colonel’s mistress Matilda, in part for her freshness in look and energy. “She hadn’t done too many things. So she brought that honesty and vulnerability we needed.” Others came onboard later: the seasoned stage actor Tony Oshinaike, Deyemi Okanlawon, and Martin Chukwu, in a small but memorable role.

Set almost entirely within the walls of a shadowy one-storey building, as a military coup unfolds outside it, A Green Fever is a work of restraint, in which atmosphere is as disturbing as action. The plot is deceptively simple. A man is driving his daughter from Lagos to Oyo. But when her sickness worsens, he makes an emergency stop at the nearest residence. The property belongs to a colonel secretly orchestrating a coup against the military regime. The colonel’s mistress unwittingly allows them in. But once inside, no one is allowed to leave. The house isn’t what it seems, and neither is the visitor.

The suspense is beautifully slow. Egunjobi uses silence the way others use dialogue. He lets scenes breathe, sometimes long enough that you catch yourself leaning forward, hoping for something to break. And yet nothing breaks, not until it has to. With the single-location, slow-burn format, the film is layered with the quiet menace of a country on the cusp of rupture. Open Country Mag editor Otosirieze named it the fourth best film of 2024, noting Isaac Ayodeji’s “tight script,” Kolade Morakinyo’s “efficient” sound editing, and Gray Jones Ossai’s “beautiful” score. He wrote:

Time attends story in Egunjobi’s films: in All Na Vibes, it is the unbroken present, and in A Green Fever, it is a ticking of history. His direction keeps the story open-ended, counting down.

“It’s about a coup,” Egunjobi says. “But it’s also about people who want things. People who lie. People who are trapped.”

Egunjobi’s father was a professor of botany who once co-owned a cinema house in the ‘70s, in Ibadan, with a Lebanese businessman. He was a reader and raised his son — who was born in Nairobi, Kenya — on Yoruba folktales and Greek myths, on the pages of Harlequin romances and Tell. Books became young Egunjobi’s first fascination. Cinema came later, as revelation.

When that revelation came, his father shot him one of those typical Educated Nigerian Parent looks that suggested the boy wasn’t being serious with his life. The expectation was for him to be a more respectable career person, an economist or an attorney or an engineer. He chose psychology and went to the University of Ibadan. He had never quite loved school, not until SS3, when he shocked everyone, including himself, by outperforming his twin brother. Studying psychology was a compromise, a way to earn a degree and keep his father’s hopes alive.

But after his first semester, when his results came in average, he called his best friend and said, “If we continue like this, we’ll finish with third-class. We better start finding alternative sources for our lives.” His best friend went into business. Egunjobi went deeper into film. His real education would happen there, in a campus fellowship where he became a popular drama director; in lecture halls where he wrote scripts while classmates took notes; in plays staged at the Faculty of Social Sciences; and in the quiet moments, when he realised: This is what I want to do, this is who I want to be.

He wrote his first script during his third year in Ibadan, at 18 — longhand, with a biro on white A4 sheets. It was a psychodrama influenced by the psychological density of Tunde Kelani’s Oleku and the courtroom suspense of Richard Gere’s Primal Fear. It was about a woman suffering from Double Identity Disorder, who loses grip of reality. His best friend Emmanuel Motojesi, who would later publish poems inspired by the film, named it “Blades of Ennui.”

But Egunjobi didn’t yet know how to make a film. His roommate, John Okorie, a geography student with an actor’s heart, told him, “Go find Martin Chukwu. He’s the best director around.” With a stack of handwritten pages, he made his way to the Department of Theatre Arts and asked for Martin Chukwu. They told him to check the library. And there Martin Chukwu was, hunched over a Shakespeare play.

Chukwu was intrigued, more so because Egunjobi wasn’t in the arts. Why was a psychology student writing a hundred-page script? Egunjobi typed up the script and Chukwu said, “We can do this, but we have to abridge it.” The budget was ₦30,000. Egunjobi would produce and Chukwu would direct. They borrowed equipment from Uncle Belit, a cinematographer and master’s student. They secured three days’ access to gear, gathered a crew, printed posters, held auditions, and sold forms. People showed up: Uche Elumelu, Floyd Igbo, and a young Temilolu Fosudo, who served as production manager. Evan Lakeshow, now Egunjobi’s go-to production manager, was the gaffer.

Editing Blades of Ennui revealed how much he didn’t know. He lost files and sound. Editors disappeared. Some took money and delivered nothing. It left him humiliated, particularly when the film was screened at Theatre Arts Hall. “I was proud, but I wasn’t very happy,” he recalls. “I felt I was better than this.”

He would learn everything, he swore: how to shoot, how to record sound, how to edit. He downloaded books from the New York Film Academy reading list, read scripts on IMSDb, devoured textbooks and reviews, and watched films like they were scripture.

In between short films that never got finished and “embarrassing” sketches he uploaded to Facebook and is now committed to digging up and deleting — including Baba Landlord, a comedic series he shot, starred in, and edited himself — he got his break as a screenwriter. A friend connected him to the filmmaker Femi Odugbemi, who was looking for writers for a project called Gidi Blues. Egunjobi couldn’t make the Lagos pitch meeting, so he sent a dossier that included a logline, synopsis, character bible, and even an unprompted dialogue sample. He got the gig. Meeting Odugbemi changed his approach. Sitting across from the veteran writer and producer, hearing that his first draft read like a radio script, receiving a one-hour lecture on screenwriting that felt like a masterclass, Egunjobi entered film school by other means. “That one hour,” he tells me, “still drives me today.”

He went on to write more Yoruba-language projects, corporate content, and passion projects with his close collaborator Isaac Ayodeji. They amassed nearly 50 scripts, many never produced. And all the while, Egunjobi was making short films — Amope, Don’t Be a Nollywood Stereotype, Musomania — and documentaries — Ibadan Life and Black Crown. He tells me that Amope became so locally popular within Ibadan that many households sampled it or knew about it. Sometimes he borrowed DSLR cameras, other times he used a DJI Osmo. Many times he made up for poor lighting with clever framing. He was building his aesthetics, slowly.

In 2021, he released his debut feature film, In Ibadan. It was made with no budget; only a camera, some lighting, friends, and desire. And it shows: the film breathes like something made by people who had nothing to lose but their vision; who, as Egunjobi puts it, “had this desire to make a film and really make it for nothing.”

The same year came All Na Vibes, an unvarnished story set against the backdrop of a crippling university strike and an undercurrent of political unrest. Three out-of-school teenagers, Abiola (a haunting Tega Ethan), Lamidi (Molawa Davis), and Sade (Tolu Osaile), grapple with separate and connected existential crises, about what to do with their lives, and get into troubles beyond their fields of vision. Shot in a neorealist style, it packs the kind of emotional punch that comes from access to lived experience. The film was his breakout. Netflix acquired it for streaming in 2023. Open Country Mag named it the fifth best film of that streaming year and Ethan’s performance as the year’s eighth best. For many viewers, it was our introduction to his oeuvre.

That Egunjobi is self-taught lingers like a watermark across his body of work, in how he grounds his aesthetics in an urgency of subject and intimacy of place. The ancient city of Ibadan, where he grew up, is the setting of most of his films. He works mentally submerged in his memories of Bodija, a leafy vicinity that smelled of both life and intellect, plants in full bloom, tranquil. He keeps memories of growing up among soursop, pawpaw, mango, coconut, and palm trees — all of which find their way into his films. Forests are his playground. “I didn’t set out to be a filmmaker who shoots outdoors,” he says. “It just happened. But now I realise I’m always drawn to nature.”

He keeps aware of other living moments, of watching his father drink beer with friends on the veranda, laughing and arguing about politics in Yoruba and English. There was order, too — weekly meetings in the neighbourhood with tea and sandwiches, where judges, professors, and lawyers debated community development. The duality of having lived a comfortable life and having experiencing the grittiness of the other end of the city gives his films their spatial depth.

To those rhythms of tranquility and thoughtfulness, he added restraint. “The minimalist approach started partly out of necessity,” he tells me. Working with tight budgets, he learned early to strip scenes down to their emotional core and with only a few cast members. “You ask yourself: What’s the heart of this moment? What do I really need to make it work?” What began as a cheaper means of filmmaking grew into style.

One trademark of his is the long shot. “They allow me to hold space,” he explains. He defines them as metaphors: for memory, for regret, for tension. In In Ibadan, it was memory that meandered. In Crushed Roses, it was poetry. In A Green Fever, claustrophobia.

In time, that discipline evolved into a visual language that privileges stillness over spectacle. While he references the Coen Brothers occasionally, it is Yasujirō Ozu who truly shaped his sensibilities. From Ozu, he learned quietude: “Ozu and Tarkovsky taught me that the frame can be sacred.” From Quentin Tarantino, he picked up structure and tonal play. And from Tunde Kelani, he saw what it meant to tell Yoruba stories cinematically and sincerely, even with limited means. “You don’t need spectacle to make something powerful,” he says. “You just need honesty, rhythm, and precision.”

Does he have a personal philosophy? “Not one,” he says, “but a few guiding ideas.” The first: higher art should provoke higher thought. His films are meant to linger, not just register. And though his stories often lean dark, he resists despair. “There’s already enough hopelessness in the world. I always want some thread of grounded realism. Something recognizably human. Life is messy, people are flawed — but there’s still meaning in the chaos.”

While All Na Vibes pushed Egunjobi to a wider audience via Netflix, it was A Green Fever that gave him the career leap he needed and solidified his creative partnership with the production company Nemsia Studios. His mentor Tomi Walker had introduced him to Nemsia co-founder Derin Adeyokunnu, who tasked him with producing a corporate documentary for a bank. He handled it with the same care he would have given a feature film, and, step by step, they brought him closer into the fold. He read early drafts of Nemsia creative director BB Sasore’s historical and faith allegory Breath of Life, offered notes, attended story meetings, and scouted shooting locations across Ibadan, many of which were eventually used. By the time production began, he was second unit director, running a team that handled inserts, landscapes, and B-roll. When he pitched A Green Fever, they picked it up.

While shooting A Green Fever, Egunjobi continued to develop ideas for his standby folder because: “You never know when an exec will ask, ‘What else do you have?’” After the success of A Green Fever, Nemsia asked him just that. He had a few options. But a project titled “One Bad Turn,” with its brooding premise and layered tension, seemed right. He pitched it alongside another titled “Pyramid.” Nemsia liked “One Bad Turn.” They asked him to expand it. And so began a ten-month writing process, in collaboration with Isaac Ayodeji.

“The studio was involved from the beginning,” Egunjobi tells me. “It was very collaborative. They’d send back a draft with notes, we’d go back and forth. Sometimes we’d argue, but it was always productive.”

The script, about a smuggler, was lean at first, and something felt missing. That was when they introduced an Ife bronze head. Here was the gravity they’d been looking for. The artefact transformed the story with history and moral weight, and with those came meaning. After the rewrite, “One Bad Turn” as title no longer captured the spirit of the story. It felt generic, too much like something else. “We searched for weeks — months actually — and nothing landed,” Egunjobi tells me. Then, five or six months later, a Yoruba proverb came to him: “Afopina tolohun o pa fitila, ara e ni o pa.” It loosely translates to: “The moth that is boasting of quenching the lamp’s fire will be consumed by the fire.” He called the film The Fire and the Moth.

“Iti represented the soul of the story — the struggle, the destruction, the inevitability,” he says. The fire, after all, was literal in the film. The moth represented all the characters, drawn to danger, to the flicker of something they can’t resist.

The Fire and the Moth is about a trail of greed and pursuit. It follows Saba, a smuggler ensnared in flight after stealing a rare Ife bronze head. Tayo Faniran delivers a compelling performance as Saba, embodying a man burdened by his choices. Jimmy Jean-Louis portrays a relentless enforcer. Egunjobi tells me that while the film draws visual influence from noir and narrative mood from the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men, its soul is undeniably Nigerian. Some critics have compared it to Kunle Afolayan’s seminal 2009 film The Figurine, in which a stolen artefact is the invisible character that moves the story.

“We were drawn to themes of time and dark, irreversible choices,” he says. One learns, a few minutes into the new film, that he is also not in a hurry to drive home that point. There is a loitering in those first frames, but it is the patience of a director who trusts the moment to yield its truth. His films do not so much dig as expose, gradually, the pain behind stillness. Each invites one to look again, until they themselves become witnesses of, even participants in, quiet, moral implosions. The Fire and the Moth is the culmination of his violent worlds, of characters trapped in their greed or the folly of others. With the film now on Prime Video, it may become his most visible work yet.

But visibility is not the point. Importance is. “I fear making films that are not important,” he confesses. And by important, he means urgent, grounded, true. His definition of success isn’t views or festivals, though he’s had those. It is resonance. Does the film linger? Does it provoke? Does it ask something difficult? ♦

Edited by Otosirieze.

CORRECTION, July 9, 12:13 a.m. WAT: William Benson appeared in a film called Herbert Macaulay, not “Edward McCauley.”

CORRECTION, July 9, 12:13 a.m. WAT: Taiwo Egunjobi was born in Nairobi, Kenya, not Ibadan.

If you enjoyed what you just read, consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

No One Covers Nollywood and African Literature Like Open Country Mag

— The Best Films, TV, and Performances of the Year: 2023, 2024

— Rita Dominic‘s Visions of Character

— The Epic, Transformative Comeback of Chidi Mokeme

— How Leila Aboulela Reclaimed the Heroines of Sudan

— Chinelo Okparanta, Gentle Defier

— The Next Generation of African Literature

— In Dika Ofoma‘s Short Films, the Drama Is in the Mundane

— How Dakore Egbuson and Tony Okungbowa Traverse Trauma in YE!

— With the S16 Film Festival, an Arthouse Collective Locks Its Focus

— How Tolu Obanro, Nollywood’s Top Composer, Crafts the Sounds of Its Biggest Hits

— The Methods of Damon Galgut

— Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is in a Different Place Now

— How Teju Cole Opened a New Path in African Literature

— How Mami Wata Swam to Sundance

— With Novels & Images, Maaza Mengiste Is Reframing Ethiopian History

— How Tsitsi Dangarembga, with Her Trilogy of Zimbabwe, Overcame

One Response

A superb piece by Bube Orji. I really enjoyed reading the conversation with Taiwo Egunjobi. I have seen 3 of his feature films and look forward to following his evolution into a powerful film maker.