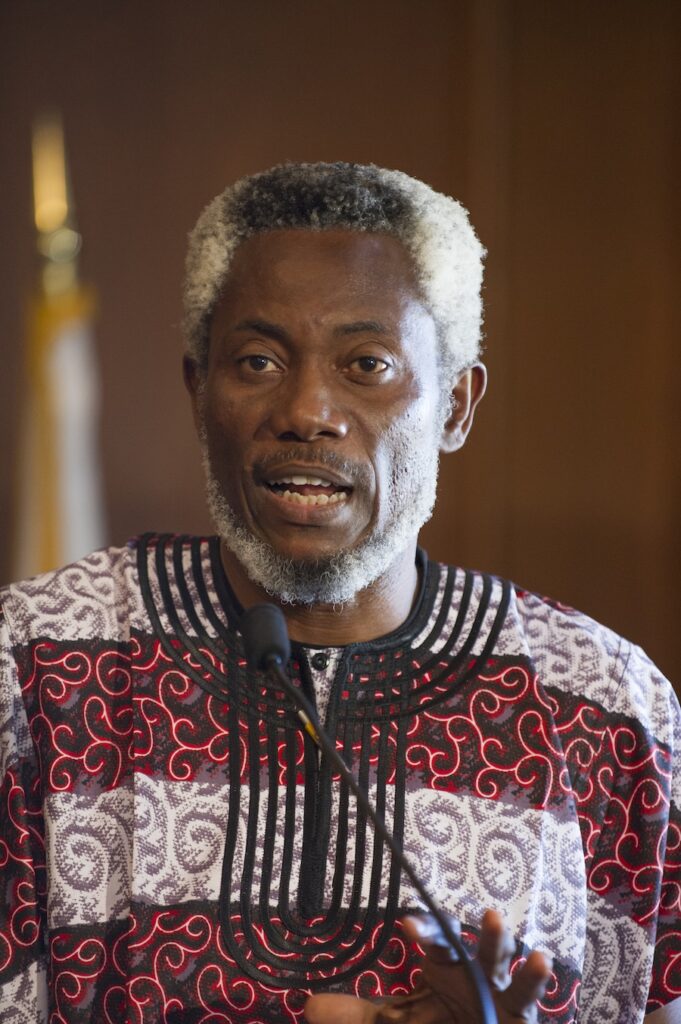

It was the heart of the wet season, in early August, when I arrived Chuma Nwokolo’s residence in Asaba, and the rains descended as I began knocking on the gates. Nwokolo came out, in his teal senator wear, with an umbrella. He is, famously, tall, about 6’4, lanky, and sports a trimmed sagely beard. It is a huge one-storey building, a balcony jutting out, supported by pillars, forming a garage for his vintage Chrysler and Mercedes. Inside, the white bookshelves blend with the white walls, and natural light fell in from the curtainless windows. On the tables were a printer and papers from his law practice, and artwork by the Igbo painter Chiagoziem Nneamaka Orji, and from the shelves peeked a diverse array of fiction, poetry, and memoirs: Teju Cole’s Open City, Tade Ipadeola’s Sahara Testaments, Michael Powell’s A Life in the Movies, Ken Saro-Wiwa’s A Forest of Flowers, and Onslow and Plaut’s Robert Mugabe. Beside them was a copy of my debut novel, Loss Is an Aftertaste of Memories. Nwokolo is known to support young artists. Offering me a seat, he made coffee for us.

Nwokolo is a significant writer of the Third Generation of postcolonial Nigerian literature, and, with his short stories, one with a remarkable range of subject matter. His best-known collection, Diaries of a Dead African, is the rare funny African satire; its characters endure tragic but obscure struggles in a classist society. His other collections include African Tales at Jail Point, The Ghost of Sani Abacha, and the two-volume How to Spell Naija, which spans 100 flash and short stories. There is also a novel, The Extinction of Menai, which takes him into speculative fiction. Lesser-known are two collections of poetry and two novellas he wrote as a teenager.

At the Umuofia Arts and Books Festival last year, he used the example of Chinua Achebe to describe his belief in the message of fiction. “When elders have gotten to that place where seriousness does not work, they have to employ humour to talk about the difficult things,” he said. “So that the recipient when he laughs can admit it into his heart without [being distracted by] the full weight of the message.” It was why he was influenced by the Cameroonian novelist Ferdinand Oyono’s The Houseboy. “The story was so sad, but the ability of the writer to write it in such a way that it is funny yet not lost on you — it made such an impression on me.”

He may have the philosophy of novelists, but it is in the short story form that he sees himself best. “The short story encompasses the African oral tradition more, where the story is brief and didactic,” he told me. “When you observe an event, which happens around you, it is the short story form which encapsulates it, because it is punchy.” His response reminded me of the Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz who once said: “When you spend time with your friends, what do you talk about? Those things which made an impression on you that day, that week. . . I write stories the same way. Events at home, in school, at work, in the street, these are the bases for a story.” But Nwokolo’s awareness and observation stem from necessity. “My kind of memory makes me write to preserve my thoughts. I mostly only remember what is recent.”

That necessity developed early, in his teenage years in Lagos. His family had gone there from Asaba after the Biafran War. They’d had him in Jos in 1962 and fled to Asaba in 1967, when the war broke out. When it ended in 1970, they moved to Lagos as Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) and lived in Ebute Meta, Surulere, and Ikoyi, where he completed his secondary school education. It was there that he began writing. At the local government library opposite the High Court, he borrowed and returned books after only a few days. The librarian took note and chided him for taking books he did not like. To keep borrowing, he had to convince her that he did finish the books. In time, he read through the shelves, and with no new books left, he began to focus more on his own thoughts.

“I learned at the time that if you were someone who thought a lot, then you must write a lot,” he said. “I wrote as a way of documenting things passing through my head and I couldn’t hold them for long.”

Gradually, he processed those thoughts into stories. He completed his first novella. A cousin introduced him to Agbo Ario, an editor at MacMillan. The Extortionist was published in 1983, under the Pacesetters series. By then, he was studying law at the University of Nigeria, Enugu Campus. The next year, he was called to the Nigerian Bar. His second novella, Dangerous Inheritance, also written as a teenager, appeared in 1988. Nwokolo deemed that period “the first phase” of his writing.

His time in university and the first 15 years of his legal career coincided with almost uninterrupted military regimes in Nigeria: General Muhammadu Buhari overthrew the democratically elected President Shehu Shagari in 1983, only to be overthrown by General Ibrahim Babangida two years later. And after Babangida installed the Interim National Government led by Ernest Shonekan in 1993, General Sani Abacha seized power. In that period, the publishing industry suffered not just from dictatorial restrictions but from bad economic policies like the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP). In that national turbulence, he realized he need to exert self-discipline.

“I told you the price I had to pay to make it possible,” he said. “I cut off women and alcohol, and writing became for me a moonlighting activity whenever I returned from the chambers. I would sit down and do whatever little writing I had to do for the day. I had no compulsion to publish at the time, but I never stopped writing.”

It was not until 1999, the year democracy returned, that he published again. It was a novel-in-stories, African Jail at Bail Point, inspired by his experience with the police and criminals. For the next decade, he lived in the United Kingdom, with a stint as resident writer at the Ashmolean Museum. His short story “Diary of a Dead African,” about a poor farmer suffering in a neglectful society, was published in the London Review of Books. It was the first in a series of similar stories that he collected, in 2003, as Diaries of a Dead African. The book does not just portray how society becomes conveniently blind to suffering citizens; it shows how people are cheated of a potential means of survival by the complicit silence of others. Its portrayal of the overreach of a local women’s group parallels that of the Umuada in contemporary Igboland. This was Nwokolo’s second phase: stories of institutionalized oppression, told with inviting, unbridled humor.

The literary landscape was in transition and digital publishing was becoming popular. In 2007, Nwokolo started a literary magazine with the poet Afam Akeh. They gave it a descriptive name: African Writing. They published 13 issues, four in print. Their final one, in 2013, was a collaboration with the first edition of the Ake Book and Arts Festival.

“At the time the magazine came out, it received significant engagement,” he recalled. “Even though we published African writers primarily, we also published a gamut of other writers. We were excited. We gave many writers their first platform. And looking back today, I am satisfied with how we spotted the talents. One story that comes to mind is Dike Chukwumerije’s ‘Bus 73.’”

The Third Generation did not enter the scene with as many publishing opportunities as the writers before and after them. Most of the literary works of that time were self-published. So the Internet boom was a remarkable opportunity.

“My generation has probably experienced more change than any generation,” Nwokolo told me. “We saw the era of publishing in the 1970s and ‘80s, experienced various military regimes, the coming of the Internet, and now. Those changes affected us writers a lot.”

The late 2000s and 2010s saw Nwokolo traveling the continent, visiting places not just physically but also, as he put it, “historically.” In Kenya, he visited an ancient city. Walking along those walls where people last lived centuries ago, he felt stuck, emotionally. It was a provocative experience. He launched a travel column for African Writing, called “Place Names,” and began exploring “emotional geography.”

“As a teen, I realised that with the emotional attachment I had to homes and neighbourhoods connected to loved ones — as they moved on or died, my connections to those places morphed,” he said. “They were not necessarily extinguished — because connections can sometimes be ritualized and historicized by elaborate burials; think the Igbo Ukwu archaeological sites, whose excavation can rekindle connections across alien centuries. So the incantation, recitation, or excavation of histories, private or public, can rekindle our human connections and create invigorating meaning for our few seasons in this world, whether in our personal lives or in literature.”

When he visits a place, he first visits a museum, to get a sense of history. Once, at the British genealogical library in Kew, he met octogenarians and nonagenarians researching their own ancestries. He digested it in the context of his own personal history. “In our younger years, we think more of urgent needs like shelter, sustenance, and how many women we have had. But as we grow older, we tend to become more connected to what our ancestors did and how they lived. We begin to see ourselves as familiar. And you’re asking yourself, where do you fit in? That your life, you know, means very little. But where do you fit in — in the arc of the struggle of ancestry? Are you similar to your parents or your grandparents? How many cars did you buy? How many women did you have? As you grow older, you find it’s quite meaningless. Sadly, in oral societies, at the dusk of life, when our parents and grandparents were dead and buried, all our living libraries and windows into the past were closed for good.”

He writes from his connection to the history of a place. In England, he couldn’t, because he was detached from British historical reality. “In the Ashmolean Museum, I was struck by its significant holding of African antiquity. I was confused how all these artefacts came out of their countries of origin.” It was a feeling of revolt, a desire to see the artefacts returned to their point of origin. “But then I visited the Igbo-Ukwu Museum, and it was striking how empty it was. And the few artefacts there were more of an ethnographic, as opposed to historical, nature. I found it hard then to argue for a repatriation of the artefacts at the Ashmolean Museum because, in Nigeria, the attention to things like this is not impressive.”

One trip that shocked him was to Mauritania, two years ago. He was driving northwards from Namibia, up the length of the continent, but his car was detained in Cote d’Ivoire. So he took public transport to Mali and flew to Mauritania. He arrived at 3 a.m., and an airport attendant began to talk to him, unprompted.

“My idea of Mauritania was of a place where Blacks were being oppressed,” Nwokolo said to me. “But the reality was more scandalous than I thought. The airport attendant said that in the entire hierarchy of the army, there is not a single Black person. It’s all like that. The whole government. And Blacks are one third or more of the population. And the worst is that there is a religious colonisation. Religion comes in and makes slaves. It breaks your mind. It prostrates you to your colonists. And then you are — you are incapable of anything.”

In a museum in the capital city of Nouakchott, he met a man his age who had brought his nephew. “He told me that he’s a Muslim. They were all Muslims. And that he believes in his faith. But he realized that there were things that he had in his village when he was going abroad that were completely destroyed by Islam. They don’t exist anymore. And so he has a sense of mortality. So he brought his nephew here to show him those things and to explain what they were. And he realised now that their religion has completely eviscerated everything. And, you know, when I go to these places, because I’m not in their religion, they open up to me in a way they never would to their fellow countrymen. He was not even saying this in the hearing of his nephew. He told me that what he regrets bitterly about this religion is that it removes what he is. Because he has a sense that who he is is gone. He remembers the village, all these things, and that they were what made his father and what made him. But it’s gone. And this is what he brought his nephew to see. The worst is that, these people, they have no agency. The entire government.”

Nwokolo’s historical consciousness of place had shaped his 2012 collection The Ghost of Sani Abacha. The stories range from romance and family life to economic hardship under the Abacha dictatorship. “Part of what it means to understand people is to observe their behaviour under certain conditions,” he said. The shift in the Nigerian psyche since 1999 has not been better. “Under military rule, there was a sense of hope that we were on a journey to democracy, which would improve on the bad governance. Well, we have reached the destination and it is giving ‘dead end’ vibes. We have traded military dictatorship for civilian kakistocracy. Instead of military governments that come into power by the barrel of a gun, we have civilian coup plotters who break into power on the canon of bribery, armed intimidation, and judicial subversion.” In one of the stories, “High Fidelity,” armed robbers break into a couple’s house, but the wife gets sexually aroused rather than horrified, and the husband is angry. To Nwokolo, the Nigerian attitude to corrupt rulers is that of the wife.

Part of his response has been to not only write in understanding of history but to also publish according to it. The 100 stories in volumes I and II of How to Spell Naija and the 100 poems in The Final Testament of a Minor God were meant to mark Nigeria’s centennial, since its amalgamation in 1914.

Nwokolo has moved from crime fiction to class fiction, to stories of the psychological neuroses and history. I asked if any shifts in paradigm, or in his self-presentation, inspired each change. He pointed out that it was more about the chronology of publication rather than the actual timeline of creativity.

His dystopic novel The Extinction of Menai — about a declining civilisation in a race to survive — was written 15 years before it was published, predating, for instance, his public image as a bearded artist. He’d finished it locked in a cottage in Nottingham, before noticing, for the first time, that he had a beard. “I thought to myself, should I take a quick shave or go out to get something quickly? Then I decided to just go out and get something, since the shop wasn’t far. When I came back, I decided that since I had outed the look, I was keeping it.”

Generally, he didn’t write to keep up a persona. “I think I’ve been reasonably consistent,” he said. “I think my writing has become more contemplative as I’ve grown older.”

The same cannot be said about many of his peers. The Third Generation has been sharply criticized both by newer voices of the Fourth Generation and by the Nigerian public, for not collectively employing art and scholarship to shape the Nigerian consciousness, for their silent complicity as government critics were disappeared, and for outrightly enabling human rights-abusing politicians.

“The real pillars of the literary industry work in private and do not even take credit for it, even though they should,” Open Country Mag founder Otosirieze said. “When the Governor El-Rufai advocates started attacking me for criticizing rape culture, Mr. Nwokolo was probably the first person to reach out outside my friend circle. He tried to mediate before it went public and even afterwards when they tried to sabotage the careers of younger writers. He distinguished himself in a time of moral crisis, and that is why I respect him. A moral backbone in a writer means hope for society.”

We were finishing our coffee when Nwokolo told me why he was still optimistic about Nigeria. “Despite the gargantuan scale of the problems, the systemic fix is a relatively simple one. Yet that optimism must be nuanced by my greatest dream for the country, which is that her borders would one day soften to blend the country into a region of a superstate Africa.” He once described this in a 2017 lecture at Storymoja Festival, titled “Superstate Africa: Kenya, Somaliland, and the Ghost of Biafra Past.” A superstate structure, he argued, would give Africa the true independence to look after its own interests and prevent the recolonization going on in places like Mauritania and the Sahrawi Republic.

If Nwokolo has the sagely standards of traditional writers, those artists expected to also think for society, he insists they are his alone to adhere to. “It is presumptuous to write a prescription for all writers,” he said. “We are all free to muddle through, grow through and think through our identity issues and to figure out our audience and purpose. For myself, I aspire not to be a hooker intellectual. My purpose is the same as always: to be a thinker, to find proximity to my issues, to find the distance to write about them and the courage to publish. The writer that lives in times of fire is also called to be a firefighter.”

Outside, the rains had subsided. Nwokolo drove me, in his Chrysler, through the waterlogged street to the junction, where I made my way into the calm city. ♦

CORRECTION (Nov. 4, 10:14 am CT): Our story previously suggested that the “Diary of a Dead African” character Meme Jumai is a widow. It has been corrected: he is male and a divorcee.

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

Buy Chuma Nwokolo’s books. Open Country Mag may earn an affiliate commission from Amazon.

- Diaries of a Dead African

- The Ghost of Sani Abacha

- How to Spell Naija, Volume 1

- How to Spell Naija, Volume 2

- The Extinction of Menai

No One Covers Literature, Film, & Culture Like Open Country Mag

— How Leila Aboulela Reclaimed the Heroines of Sudan

— How Rita Dominic Became Nollywood’s Most Acclaimed Actor

— Chinelo Okparanta, Gentle Defier

— The Next Generation of African Literature

— The Methods of Damon Galgut

— Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is in a Different Place Now

— How Teju Cole Opened a New Path in African Literature

— With Novels & Images, Maaza Mengiste Is Reframing Ethiopian History

— How Tsitsi Dangarembga, with Her Trilogy of Zimbabwe, Overcame

5 Responses

Great exposition.

Beautiful read

This is a powerful and a truly reflexive work. Well done Michael.

Beautiful work, Michael.

This is well written. Pa Chuma has done a lot for African literature. I’m proud of his contributions.