With significant contribution from Ernest Ogunyemi.

________

Months after arriving the US in 2018, Romeo Oriogun was attacked by a man he brought home from a nightclub. The Nigerian poet was an Artist-at-Risk Fellow at Harvard then. In a memoir, he likened the incident to discovering a slain deer on his grandmother’s farm when he was a kid.

“I felt nothing,” he tells me last November. “It’s one of the mildest things to happen to me. I really felt pity for him. When I’m one-on-one with someone, I don’t care how big that person is, as long as you don’t have a gun and you’re not carrying a knife—then most times I won’t think I’m in danger.”

He was the kid who’d hold a grudge for a week and wait patiently to serve its fury. But most times he was at the receiving end of someone else’s. “Sometimes things happen to you ‘cos you allow it happen,” he says, “and you allow it happen because you know that if you don’t, what’s gonna happen will be more brutal. So you chose that lesser violence in order for the both of you to survive.”

Oriogun’s manner of relating to the world started in childhood. His family once lived in comfort: a chauffeured car drove him to army school in Lagos and they moved frequently, living in Kaduna, Port Harcourt, and Jos. He wanted to be a soldier. But then his parents parted, and, for a year, his father wouldn’t let him or his siblings visit their mother. He passed away when Oriogun was around six years old.

He went to live with his mother, Dorcas Osadiaye, and grandmother in Benin City. His mother worked as a nurse and hawked garri on the side. His grandmother worked on the farm and sold akamu. Watching them, his dream changed. He would now be a lawyer. His mother and grandmother were worshipers of Olokun, the deity of the sea, regarded in Benin traditional religion as the giver of wealth, health, and fertility. Before encountering Olokun, religion was a world he knew nothing of. He would later call himself Son of Olokun, living the faith of the women who raised him. When he began writing poetry, water would be a motif.

It was about a month to his West African Examination Council (WAEC) and National Examination Council (NECO) exams that his mother passed. His classmates crowdfunded to buy him forms for both exams. Later, after someone who borrowed from his mother paid back, he repaid his classmates’ money. The money went to helping another student who couldn’t afford exam registration.

His mother’s death broke him. “I became very unruly,” he says. To calm him down, a teacher, Mrs. Uweni, who “saved my life,” introduced him to poetry. He read John Keats’ “Ode to the Nightingale.” He didn’t know that a nightingale was a bird but he imitated the poem and wrote his first, which he gifted to his teacher on her birthday.

The wound from the loss of his mother still fresh, he applied to study Medicine at the University of Benin. He was offered Pharmacy, but he didn’t want it. The next year he applied again, but on the day of the JAMB exam he went instead to his mother’s grave. He had lived to make his father proud, then his mother, and now both of them were gone. “What am I doing this for?” he asked himself. He broke down and could not sit for the exam.

During this period, he taught at a primary school, earning N2,000 per month. His pupils were his agemates—he was 14, 15 at the time—boys with whom he played football after school. “During school, they were, like, ‘Uncle, Uncle.’ After school, it was, ‘Hey, Segun, pass the ball.’” He laughs. “It was really one of the happiest moments of my life.”

Briefly, he attended a private polytechnic where he studied Business Administration, after which he interned in an NGO focused on HIV/ AIDS intervention among young people. The pay was N10,000 naira this time, but what really gave him joy was that he was learning. His plan was to found an NGO named after his mom—until he realized that founding an NGO was not easy.

Years after leaving Benin City, he discovered J.P. Clark’s “Streamside Exchange.” Reading Obi Nwakanma’s Thirsting for Sunlight, a biography of the iconic poet Christopher Okigbo, in which Ibadan is painted as the “City of Poets,” he, having decided he wanted to write and now working with the Federal Road Safety Corps (FRSC), applied for a transfer to Ibadan.

Ibadan was where Oriogun entered the Nigerian literary scene. At Artmosphere, a hotspot, he read a poem to an audience for the first time, and they “trashed” it—deservedly, he says. Another young writer, Olubunmi Familoni, walked up to him. “Don’t take any of these criticisms too hard, everyone wants you to grow,” he said. “Do you want to be ‘a poet from Nigeria’ or do you want to be ‘a Nigerian poet’?” The first, Familoni explained, was a poet who “claims local championships but wouldn’t do the work”; the other, a poet whose work speaks to the world. At the time, Oriogun had written only two poems. If I have to do this thing, I have to do it well, he thought.

He read outside Nigerian literature—Alexander Pushkin, Pablo Neruda, Essex Hemphill. Hemphill, who was openly gay, wrote about race, identity, sexuality, and HIV/AIDS with a frank, vibrant energy. Reading him, he felt validated to make poems about queer bodies and desire. He learned to use reportorial skills, which he thinks is his favoured style of creating poems—that journalistic element of telling the reader something. He read more poets writing in a similarly non-judgmental way: Kamau Braithwaite, Derek Walcott, Chris Abani, Tomas Transtromer, Adelia Prado, Adam Zagajewski, Gabriel Okara, Okigbo’s Limits.

At Artmosphere, also, he was introduced to the Facebook poetry scene, which was big at the time. From writing on Facebook, he picked up an extemporaneous approach: he writes the poem on the spot, in no more than 10 minutes, and he does not edit; although, he tells me, he is grateful to have had very good editors work with him.

In 2015, he came across the work of the Kenyan-born British Somali poet Warsan Shire, who two years before won the Brunel International African Poetry Prize. “It was as if someone placed an axe on my forehead and split it open,” he says of Shire’s work. Two years later, he would follow in her steps and win the Brunel Prize, and fellow poets would say something similar of his own work.

One day in February 2016, Oriogun, now in Ikare, Ondo State, was on road safety duty when he saw disturbing news. Akinnifesi Olumide Olubunmi, a young man, had been lynched to death for being gay, in Ondo town, two hours away from where he was. It shook him. He was even more shook watching his colleagues justify the murder. He went home angry, and wrote a lot of the poems that became his first chapbook, Burnt Men.

Laura M. Kaminsky, an editor at Praxis Magazine and an important figure in the Facebook poetry scene (one of several women, he tells me, whom he hasn’t met in person but who contributed to his life in no little ways), took interest in the manuscript. Burnt Men was published that April, with a Foreword by the British poet John L. Stanizzi. “Not since I first read Dancing in Odessa by Ilya Kaminsky have I been so taken by a book of poems,” Stanizzi wrote. (Three years later, Kaminsky would blurb his debut full-length.)

When Oriogun won the Brunel Prize, with 10 poems from Burnt Men, the judges described him as a “hugely talented, outstanding, and urgent new voice.” He became the prize’s first openly queer—bisexual—winner, and, even more significantly, the first openly queer Nigerian to win a major African prize. Then a tirade of attacks online and offline followed, spreading outside literary circles. Resistant to the sudden notability bestowed on an LGBTQ+ writer, some people claimed that he did not deserve it, swarmed his Facebook inbox with homophobic messages. People he considered friends, writers he supported and wrote with, joined the mob against him. At a reading at the University of Benin, one such “friend” said to a room full of students that he “bought” the prize. The next month, when he was there to read, the interviewer asked: “They are saying that you ‘bought’ the prize. What do you think about this?”

“I didn’t say anything,” he tells me. (He withholds the name of the poet “friend.”) “There was nothing to say. I was already so tired of defending myself.” Twice he was assaulted on the streets. His exhaustion later turned into anger. “I had no idea that people can be very vicious. It changed me, it really changed me and the way I see the world. I realized, if you don’t have anybody in this world, you have to act like an aggressor.”

Fellow young writers rallied to his defence. They trended a hashtag on Facebook, #LetRomeoBreathe. Open Country Mag editor-in-chief Otosirieze Obi-Young, then deputy editor at Brittle Paper, wrote a blog post emphasizing “the sheer beauty” of his work and his merging of “natural talent with dedicated hard work.”

“It’s important to understand how much of this is also about class politics,” Otosirieze told me. “We have to remember that many influential writers and curators kept silent and watched it happen, and part of that was how he had come out of ‘nowhere’ and dared to be that good, and he wasn’t shutting up and being grateful that he had been ‘raised’ to a new level. He was the first, in my knowledge, to place LGBTQ+ issues in the context of class privileges in Nigeria. And here’s the fact: It is this set of working-class, home-based writers who fought for queerness to be accepted. They made impact not just in identity politics but in where I think matters the most: craft.”

There were the positives. His work—verses unbound, bursting with pomp and passion; the imagery of fire, water, flowers, radio; his use of Biblical language—quickly spawned imitators. He was barely a breakout poet and yet he had become influential. His circle expanded. By the time of his Brunel Prize win, he still worked as a road safety marshal and had transferred from Ondo to Udi, a small town in Enugu State. He lived there for a year, the only place in Nigeria he “truly felt at home.” Less than an hour away from Udi is the university town of Nsukka, where he would visit a circle of writers, journalists, and artists that included Obi-Young and the poets J.K. Anowe and Benson David, who often gathered in the home of the visual artist Osinachi.

But the negatives remained. The homophobic witch hunt exacerbated his bipolar disorder and he spoke about it. His life became characterized by danger, of living “like he’s going to die.” He says now, “It’s not something I romanticize, it’s just—there were days when I felt I had nothing to live for. Over the past three, four years, what has happened to me is that there’s this sense of life, of which reading also contributed a lot to. Reading a lot of poems about people who have been in what I’ve been; whether it’s exile or being alone, a lot of these things. You see the language of the poems, you see what they’ve done and over time that kind of poetry sank into my brain. Two of my siblings are married with kids, and I talk to their children and they just laugh and there’s a way in which those fellowships—whether it’s reading, or communicating with people, going on a walk, or also being in love—has given me a sense of belonging. Not to a place, not to even people, but to the world at large. That sense of urgency is still there, but I no longer live like I want to die.”

After the homophobic attacks, Oriogun left for Ghana, to Accra. That, he says, was where he “really became a poet.” There was an outburst of writing and intent. He published two more chapbooks, The Origin of Butterflies, with the African Poetry Book Fund (APBF) in 2018, and The Museum of Silence, with Arrowsmith Press in 2019. The opening line of the titular poem of Butterflies goes: Give a man a piano and his fingers will find music but when grief lives in walls what music will a mouth produce?

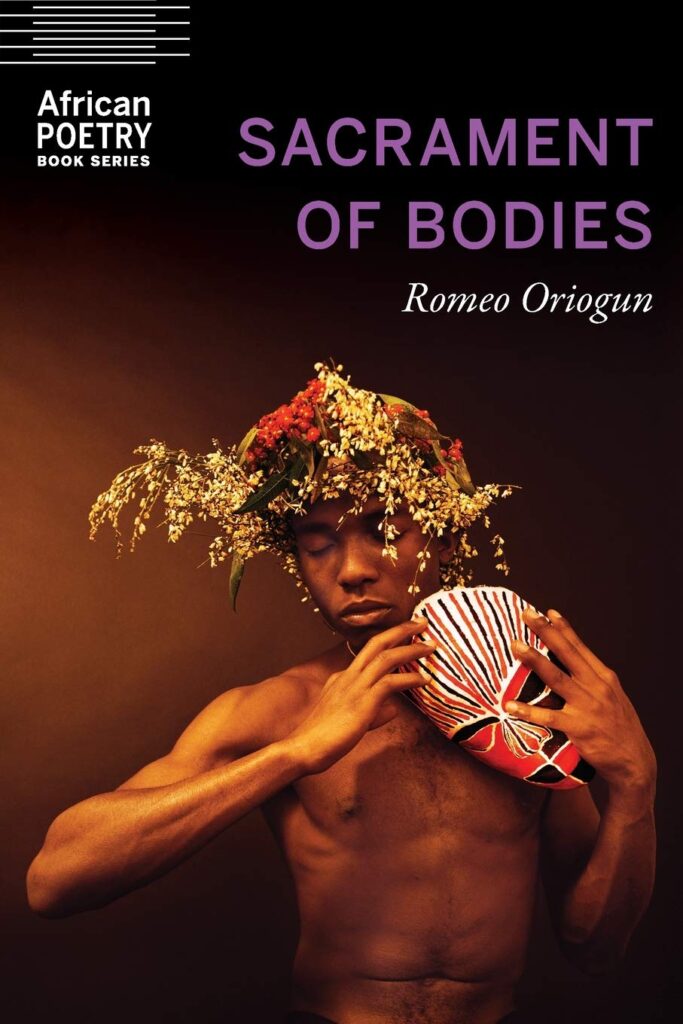

He was at work on his debut collection. An early draft, titled “My Body Is No Miracle,” was a finalist for the Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets. He retitled it Sacrament of Bodies, in homage to Chris Abani’s Sanctificum. The collection was published by the University of Nebraska Press in March 2020. “Romeo Oriogun has developed a style that is both personal and mythical,” Ilya Kaminsky wrote in a blurb, “because these poems are sensual and spiritual at once, because they give us both a story and a song, a shout and a whisper.” Ellen Bass called it “a gorgeous book filled with fiery pain and ecstatic desire.”

Where the chapbooks are personal and poignant, Sacrament of Bodies moves outwards. It incorporates myriad experiences. One poem, “The Queer Boy Remembers Colonization,” uses the charged language of prophecy to criticize religious-sanctioned homophobia. Another, “Meeting My Mother Through Death,” utilizes journalistic dedication to document a man bringing the terms of his sexual reality to his mother: I will call a name that was not given to me and whisper, Mother, I love a man the same way I’ve loved a girl.

Writing in The Los Angeles Review of Books, Erik Gleibermann noted that Oriogun explores something not common in Nigerian literature by men until LGBTQ+ writers: “a territory of vulnerability.” The body, in his poems, “speaks its own visceral language of conflicted sensuality where joy and threat can reverse in the turning of a line.”

“Romeo Oriogun’s work opened the sky for me,” said the South African poet Maneo Refiloe Mohale, whose debut collection Everything Is a Deathly Flower won the Glenna Luschei Prize for African Poetry last year. “When I first picked up Sacrament of Bodies, I was struck by his deftness at traversing his own interiority, and his ability to draw on African ancestral orality, all the while making space for the structural, the spiritual, and the sublime. There are poems and prayers from that collection that I treasure and keep close to me, and others where I can stand back and just marvel at his ear for challenging, gorgeous imagery.”

Oriogun, on his part, looks at his work critically. “When I wrote Burnt Men, I was surviving. It was a book that literally every poem was me falling and wanting to survive. I read that book and I cringe. It’s a book that’s my scars. It’s a book that I read and every poem still means something to me, and I appreciate it and I love it. But craft-wise, I was, like, damn, I could have done this here, I could have—” He pauses. “It’s like that with all my books. I only read Sacrament of Bodies when I’m giving readings. I think, for me, language is the biggest thing. When I look at my process, when I say I cringe most times, I’m cringing at the language.”

He is giving the same treatment to Nomad, his forthcoming second collection, which he began in Accra. “The difference between it and Sacrament of Bodies—miles, miles apart,” he says. “That sense of urgency has never left me. Poetry is the only language I have. I don’t fully know Benin, I don’t fully know Yoruba, I cannot speak Igbo, I cannot write in any of these languages. English is the only thing I can write in and poetry is the only thing I know how to do well. It’s kind of, like, the language of my own being. I always try to own it, and push it, and ask myself what that language is doing for me.”

The Nigerian poet Othuke Umukoro read Burnt Men when it came out and took Oriogun as an influence in language. “For many poets in Nigeria, his work opened a door to ‘the body,’ to its constraints and celebrations which by extension is the very core of our humanity,” he said. “The language questions, bears witness and even unearths the ruins and treasures of our world. There is that feeling that tenderly and sometimes ruthlessly lies between the lines.”

Last year, as Oriogun followed in Warsan Shire’s steps, Umukoro followed in his and won the Brunel Prize.

He is in his house when we speak again in late December. He is in a grey sweater and wears the demeanor of someone catching a much-needed break. Ever since he moved to the US, it has been one engagement after the other: at Harvard for fellowships, at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop for his MFA, at the Oregon Institute for Creative Research, and at Iowa State University, where he is a postdoctoral research associate.

And then last November, his poem “Cotonou” appeared in The New Yorker. The significance was not lost on him. Here he was, someone who couldn’t obtain a bachelor’s degree in Nigeria but now had an MFA and was teaching in America, a writer without a literary agent, a writer denied opportunities due to his background, now in the most prestigious literary magazine.

He has been fortunate to find mentors in America. “I was lucky to meet Professor Elizabeth Willis, who was my thesis supervisor. And the first thing I told her was, ‘I don’t want to be an American Poet,’ and she asked what I meant by that and I was, like, ‘I want to write poems devoted to my experience as a Nigerian and to speak about where I come from.’ We started these discussions in which she would give me recommendations to a lot of books by writers around the world, South Africa, Sudan, Poland, Russia—just a wide reading list. When I started teaching that’s what I did. I’m always very curious about what’s happening in poetry around the world. We hear about America all the time and there’s a way it blinds us to what’s happening elsewhere.”

Such concerns for upcoming poets led him and the poet Chibuihe Obi Achimba to found a briefly lived magazine for queer writers called Kabaka. It was inspired by discussions they had in 2016 when most African magazines rejected their queer-centric poems. It was named after Kabaka Mwanga II, the monarch in ancient Buganda—present-day Uganda—who was queer. In the Introduction of Kabaka’s only issue, he wrote, “We must find a language to write into existence what has been done to us.”

Our conversation shifts to literary curation and the roles of power and class. “Nigerian literature, as it stands, is a very middleclass thing,” he says, after much contemplation. “It touches the lower class as a form of benevolence. For example, a lot of the books being sold in Nigeria are very expensive, the only way you can get books sometimes is if someone buys for you or you’re walking under the bridge and you get to second-hand bookstores and buy from there. You think of the books available to the lower classes, the Harlequins, the Mills and Boons, just escapist romance.” He can’t stop thinking about what it would have meant if children like him had access to better libraries.

“I’m someone who thinks about power a lot,” he continues, “and I think I have to do that because when I was in Nigeria I hated the fact that people in the diaspora controlled the kind of literature we consumed and how literature is curated. A lot of the journals and magazines were founded by people who lived in the diaspora. I think the only magazine that was founded and run by a Nigerian based in the country was Praxis. People who curate spaces have to do what they have to do because if they don’t no one fills in that void. I think too much to be that kind of person. And I try to help when I can, in a way that doesn’t consume me. Voices matter: we in the diaspora and voices in Nigeria have to understand that no one is more important than the other. But then they’re instances in which certain voices take precedence.”

He is optimistic about contemporary African poetry. “Prior to seeing someone like Gbenga Adesina coming up and winning the Brunel Prize, Nigerian poetry was stagnant. Now what has happened is that there’s a lot of room for people to come up.”

He mentions 20.35 Africa, founded by Ebenezer Agu, and the anthology Memento, curated by Adedayo Agarau, as platforms he loves. “With 20.35 Africa, there’s constant curating, bringing in new editors, introducing people to new young poets. It kind of complements what the APBF does with their chapbook series. I feel like writing, no matter where you are, is always in conversation with each other. I feel what I would love to see is a journal that would have conversations with Black poets around the world. Not just Africa, but in Britain, in the Caribbean, in Asia, in the world. This is a vibrant generation in terms of what we’re writing about, how we’re writing about it and the diverse ways in which we assist each other, whether it’s influencing each other or how we push each other.”

Oriogun has always lived a nomadic life, which he traces to his mother’s death. He wrote Nomad to mirror the peculiarity of journeys. He traveled through West African cities as he wrote. The book progresses from the emotive, high-wire poems of previous titles. By tempering his language, he emerges as an observer, his eye trained not only on people and events but on places and their solemn histories.

“Someone once told me my poems sound very formal,” he says. “And I’m, like, yeah, every poem I write is me having a conversation with my mom. And when I talk to my mom it’s very formal until we break down and start laughing. The more I get older, the more I realize that urgency is not running all the lines. What I’m writing now recognizes urgency in the language itself and not the speed of the lines or even emotions.”

Nomad will be published first in Nigeria, and then in Canada, by Griots Lounge. “I think a poet belongs to his people,” Oriogun told Africa in Dialogue about his decision. “It’s a very strong belief of mine; a poet belongs to his community, to his country. My first duty is to my city. There’s something about violence and survival that evolves every single day and when you leave a city, a city leaves you.”

Maneo Mohale, who edited a draft of Nomad, sees Oriogun’s work as pivotal. “He punctures an insidious silence—one that would have us believe that queer African poetry does not exist, or that queer African poets are only imitating the West. I think his work signals to younger generations that another world is possible, and that we can harness our various abilities to tell our own stories beautifully, dangerously, playfully, and in deep conversation with the past—as a way of ushering in a future where our humanity can be celebrated and honoured without compromise.”

Oriogun wants to be even more unrestricted. “When I try to write about Nigeria these days, the poems feel incomplete, so I turn to other parts of Africa and write about them. And what that has done for me, it has given me the sense of ownership and belonging I never thought I’d find. A friend told me about finding home on the road, and I just laughed because for me that’s not it. I find home in those little places I stay for a while.” He laughs. “I don’t consider them roads, I consider them a phase.” ♦

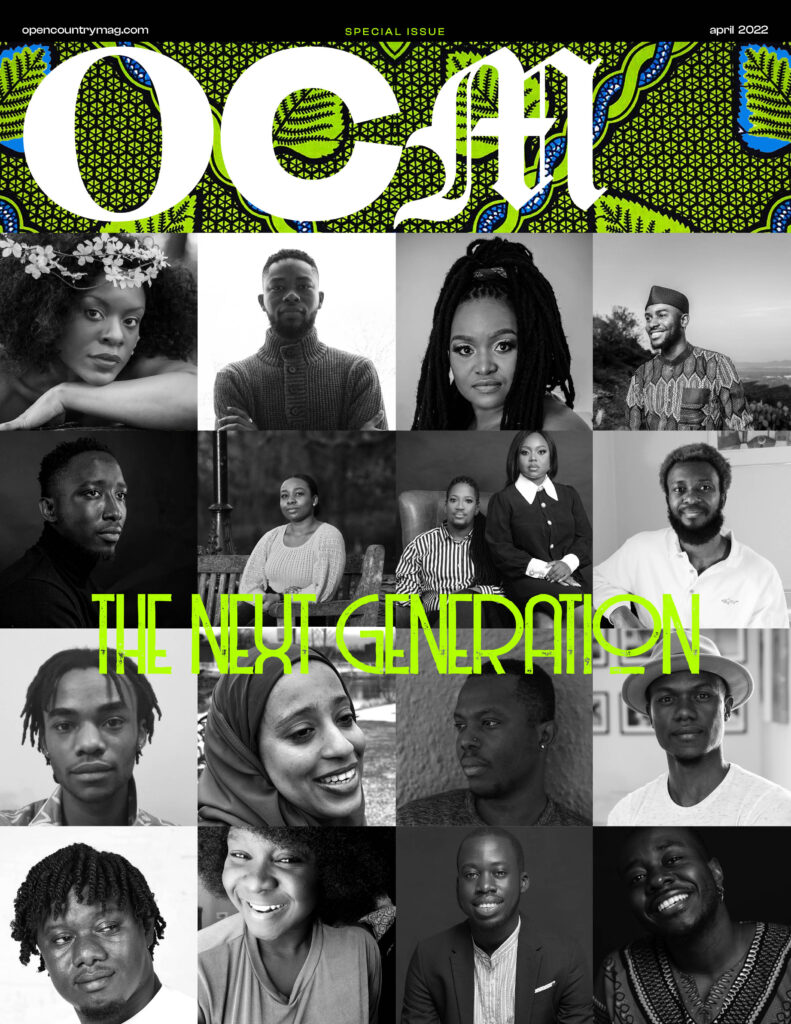

“Romeo Oriogun Wrested Poetry from Pain” appears in The Next Generation special issue of Open Country Mag, profiling 16 writers and curators who have influenced African literary culture in the last five years, curated and edited by Otosirieze Obi-Young.

17 Responses

Words can’t describe what I’m to say about Big Boss, Romeo.

Thanks for this !

This is awesome story that’s telling a hopeless person no loose hope .

A touching and compelling story; depicting triumph over evil and hate. Quite inspiring.

Beautiful ❤️

Wwlldone Romeo… Proud to have met and known you.

I enjoyed this. Well done!

This is both beautiful, captivating and inspiring. I love the way the narrative is a reflection of one for all. More wins, Romeo!

Nice one I someday wish to be like you uncle Romeo,more grease to your elbows. God bless you sir

Nice one I someday wish to be like you uncle Romeo,more grease to your elbows. God bless you sir. Thanks for the inspiration.

Wow!

Splendid!