Ten years ago, when he first broke into the South African writing scene, Nick Mulgrew looked around and felt trapped. He was in his 20s and had scooped the National Arts Festival Short Sharp Stories Award as well as the South African Arts Journalism Awards Special Silver Merit for Features. There was attention from abroad, but at home the doors of publishing houses remained closed.

“I was frustrated with the opportunities afforded writers,” he told me. “The industry was, and still is, dominated by multinational and corporate interests. The vast majority of books are imported. Compared to my peers in the UK, the pathways to publication in South Africa weren’t clear, or otherwise didn’t exist, especially if you wrote poetry, short fiction, or things unapologetically literary. I thought there had to be a better way. A space for young South African poets whose work was dismissed or ignored by larger publishers.”

Impatient, he sketched plans on his laptop for a small poetry press, to be based in Durban. He called it “uHlanga,” a word that, in Zulu cosmology, connotes origin: the reed bed from which the creator Unkulunkulu brought humanity into the world. The press would be a first step onto land. The name was his way of staking that poetry, too, could emerge from obscurity.

With the faint bravado of someone who knew the odds but not the future, Mulgrew poured his own money into a slim volume. He saw his debut collection, the myth of this is that we’re all in this together, as a “first pancake” — sacrificial, absorbing mistakes so later ones would be better. “If it was going to suck, it would only damage my own reputation, and nobody else’s.”

That first pancake turned out edible. Then came more. By the time Thabo Jijana’s Failing Maths and My Other Crimes and Genna Gardini’s Matric Rage were published in 2015, both backed by a grant, uHlanga had made enough noise to be noticed. Both books won awards. Print runs multiplied. A real press had emerged.

But the turning point did not arrive until Mulgrew went on Facebook sometime in 2016 and wrote to the young poet named Koleka Putuma, asking if she had a manuscript. Indeed, she had a searing collection exploring blackness, womanhood, and history; incendiary poems demanding justice, insisting on visibility, and offering healing. Moving from religion to politics and relationships, Putuma was interrogating the authority of ideological preserves. In 2017, uHlanga Press published that book, Collective Amnesia, and it broke open the market — and Mulgrew’s own ligaments. He sprinted across the Frankfurt Book Fair, knee giving way, to secure a European translation deal. Over 6,000 print copies sold, he said, a dozen launch events, stacks of packages at the post office, and, suddenly, a South African poetry collection was an event, urgent and unignorable.

“I think we did a good job together,” Mulgrew said leisurely, understating that moment. It was, in truth, the beginning of an era for uHlanga Press. In Africa, there was acclaim. Jijana’s book won the Ingrid Jonker Prize in 2016. Putuma’s won the Glenna Luschei Prize for African Poetry in 2018, an award that Maneo Refiloe Mohale’s Everything Is a Deathly Flower also won in 2020. In Europe, there was multilingual interest: translations into the German, Swedish, Danish, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch.

South Africa has 11 official languages, and Mulgrew shared that uHlanga Press had begun working in a few — isiXhosa, isiZulu, and Afrikaans among them. “Most South Africans are multilingual. Our literature should reflect that, even if it’s not seen as commercially viable right now.”

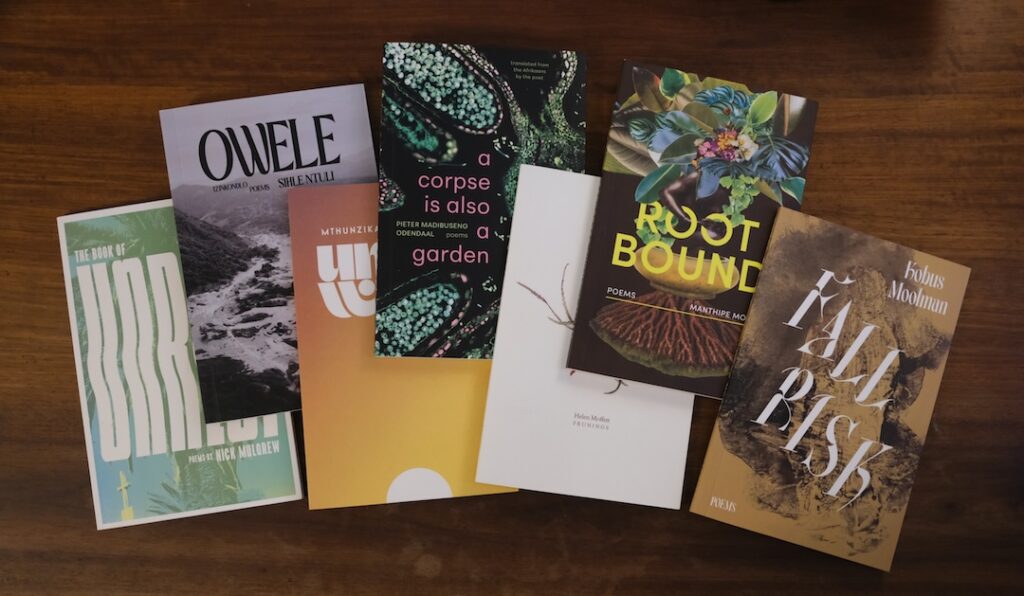

The emergent set of South African poets that uHlanga turned to, right after Collective Amnesia, illustrates this. Sihle Ntuli’s Owele includes poems wholly in isiZulu. It “has been an important act of reclaiming,” Ntuli wrote to me. “I feel my isiZulu poetry holds the spirit of my origins and descendants. There is an act of preservation taking place.”

Another book, Pieter Odendaal’s a corpse is also a garden, began life in Afrikaans, before the author self-translated it into the English. Like Ntuli, Odendaal sees uHlanga Press as a space where language carried across tongues can reach further.

“Growing up queer in Bloemfontein has a way of pushing one to the periphery,” Odendaal said. “Writing in Afrikaans is a prime entryway into its complex history. But translating my poems into English enabled me to reach readers I have always wanted to move. And uHlanga, with its focus on contemporary South African poets, many of them from my generation, seemed like the perfect home for this expansion.”

One poet, Manthipe Moila, threads Sesotho and Korean words in her collection Root Bound, an interrogation of place, belonging, and home. She first encountered the press through Putuma’s work. She was a literature student then and took later inspiration from their other poets, including Mohale and Milk Fever author and Stoep Collective co-founder Megan Ross. She saw uHlanga as a place where she could experiment.

“There was the fear that using hangeul, the Korean alphabet, might alienate the South African reader,” Moila said. “But we found a middle ground that elevated the poetry while maintaining an internal logic.”

It matters to Ntuli that uHlanga is homegrown: it allows his work to take root first in South Africa, to make its case there before reaching the rest of Africa and the wider world. He recalled when he first learned about Mulgrew’s work. “uHlanga was still set to be a literary journal at the time. Little did we know it would end up being one of the most important poetry presses in contemporary South African poetry.”

There are barriers to publishing good, original poetry, and Mulgrew, a White writer in a racially torn and economically unequal South Africa, has a front seat to it. “It can be strange to introduce a radically political Black writer to a predominantly White suburban audience, or vice versa,” he said. “The reception of texts in South Africa is still influenced by inequality — economic, gender, racial.”

Those inequalities shadow everything, including cultural distribution. There are bookstores that misfile poetry, newspapers that refuse to review it, supply chains that depend on suburban shelves far from most readers’ lives. “And then the price of books,” he added. “Often they simply don’t fit into people’s budgets.”

Managing uHlanga Press means contending with scarcity. “The most obvious challenge is money. Poetry does not make money. Some books sell very well, but often the profits from those offset the losses from others. I had to make peace early on that uHlanga will never support me; it is a passion project.”

Although Mulgrew does not posture about uHlanga’s impact, staying off social media and not obsessing over reviews, he speaks of his work with clarity, as a vision already lived into permanence. In 2025, he launched another press in Edinburgh, Scotland, named Batis Books, to focus on fiction and nonfiction. But for uHlanga, which “will remain poetry-focused,” the lack of money means less expansion and more continuity: building capacity with poets, teaching them to become editors and marketers.

Financially, there is little legroom, but Mulgrew is optimistic. In the absence of a hit book, passion can run on a prestige collaboration. Last year, uHlanga and Karavan Press co-published the anti-Apartheid activist C.J. “Jonty” Driver’s memoir Dayspring, a book posthumously edited by J.M. Coetzee, who is Driver’s in-law and also wrote the foreword.

But mostly, Mulgrew’s passion is just meaningful routine. “Although it is satisfying when a writer wins an award, I’m always cheered when someone I don’t know says how much they enjoyed one of our books,” he said. “And when I see one of our books in a bookshop, it never gets old.” ♦

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

Buy uHlanga’s books. Open Country Mag may earn an affiliate commission from Amazon.

- Nick Mulgrew, the myth of this is that we’re all in this together

- Thabo Jijana, Failing Maths and My Other Crimes

- Genna Gardini, Matric Rage

- Koleka Putuma, Collective Amnesia

- Maneo Refiloe Mohale, Everything Is a Deathly Flower

- Sihle Ntuli, Owele

- Pieter Odendaal, a corpse is also a garden

- Manthipe Moila, Root Bound

- Megan Ross, Milk Fever

- C.J. “Jonty” Driver, Dayspring

You can also order the books from uHlanga Press’s website.

More In-depth Stories on African Literary and Arts Organisations and Projects

— Inside The Cheeky Natives, an Archive of Intentionality

— “Shatter That Silence”: How the Abebi Afro-Nonfiction Prize Honours Stories of Women’s Lives

— With the S16 Film Festival, an Arthouse Collective Locks Its Focus

— The Making of Songs We Learn from Trees, the First Anthology of Amharic Poetry in English

— Cameroon’s New Literary Generation Comes of Age, with Bakwa Magazine at Its Centre

— Inside Agbowó, a Nigerian Literary and Arts Hub

— From Nigeria to Canada, Griots Lounge Takes Steps for Indie Publishers

— On an Eastern Nigerian Campus, a New Literary Hotspot