When the actor Chidi Mokeme first felt a weakening of the muscles on the left side of his face, he looked in the mirror and decided that it was serious enough to call a doctor. It was late 2016, and he was on the promotional tour for ’76, Izu Ojukwu’s military drama in which he plays a major who accuses a captain of joining a botched coup and tortures him. The film had screened at the Toronto International Film Festival to perhaps the best reviews for a Nigerian feature then, premiered in Lagos to excitement, and now it was headed to the British International Film Festival, the first Nollywood film to ever be invited.

He was in the United States when he noticed it, on a break from the tour. Within days, it hit him fully, like a stroke. The skin on the left of his face sagged: forehead, cheek, jaw. Half of his face drooped, like the muscles had lost strength. Doctors told him it was Bell’s Palsy. A condition he had never heard of. Worse: it was incurable. There was no medical knowledge of its cause and so there was no remedy for its effect.

Although he knew he was lucky to be in the American healthcare system where doctors eliminated unlikely causes before arriving at a conclusion, rather than in Nigeria where it might have been misdiagnosed as stroke, it still sounded like a cruel joke. Fate, he felt, was playing a vile trick on him.

Here he was, an actor whose main tool was his face, now in the highest profile role of his career yet, in a film that would go on to set industry records, earning 14 nominations at the Africa Magic Viewers’ Choice Awards (AMVCAs) and eight at the Africa Movie Academy Awards (AMAAs). If there was one body part he could not afford to have damaged, it was his face. Without control of his face, he could no longer be a performer. And if he could no longer be a performer, he would never find fulfilment, no matter how many other businesses gave him money.

At first, he was angry. Then he was confused. Then he wept bitterly.

“You can imagine what I must have been going through at the time,” Mokeme told me in mid-May. “It made me have this continuous conversation, you know, with the Creator. I said to Him, ‘Look, when I started out on this journey, I was cocksure that this is all I wanted to do, and if I was cocksure, it must be that this was what you implanted in me. So how is it that I have done it for three decades, and just at the time when we are about to now check how the flower is blooming, you come and give me this thing.’”

He was desperate. He told God that he knew the doctors said there was no cure but that he really believed that this was a phase. He said to God, “‘Let’s make a deal.’” He said, “‘God, if You put me right back in a position where I can go back to doing this thing that I really want to do, I will bring this talent to You in such a way that even You have not seen before. I will make sure that the way I use this talent when you give me this opportunity again, there will be no doubt in anybody’s mind that this is Your doing.”

He had never thought of his acting career as his alone. He had always thought of it as fate, an appointment between him and God.

Mokeme did not originally plan to be an actor. He started in fashion. At 15, he was already doing commercials, and he broadened to work the spectrum: runway, television modeling, billboards, ads. This was the 1980s, a time before home videos, before Nollywood as the world came to know it. But there was television, and although the modeling circuit was quite different from it, the fashion and entertainment circles overlapped.

“I think the only people who were really popular at the time were on the small tube, you know,” he recalled. “People who were appearing on the popular series of the time, like Ripples and Behind the Clouds.”

His boss and agent Alex Usifo, owner of Silver Models, was on Ripples, playing a popular character called Tala Labas. But, strangely, Usifo did not try to introduce his models to acting, and Mokeme did not understand why. Although modeling paid well, he prepped for auditions and attended casting calls.

And then came the Igbo-language film Living in Bondage, in 1992, and the Nigerian film industry shot to major relevance. A new dream was born and people flooded in to share it. Filmmakers were experimenting, new production houses sprang up, and with so many aspiring actors available, they shot countless pilots and films, none of which came to light. Sometimes, when a film or series came out years later, and with a different title, even the actors struggled to recognize the productions they’d acted in.

One day, another of Mokeme’s agents, a woman named Ajufo, of Pandora Models, asked him to deliver a message to the director Zeb Ejiro. Mokeme found Ejiro on set, shooting with Hilda Dokubo and the recently late Saint Obi. Ejiro looked at him — handsome face, sculpted body, masculine swagger — and said, “Man, you look like a character we’re trying to get; do you have time to do this for us right now?” Mokeme said yes.

That film, Goodbye, Tomorrow, an advocacy flick about HIV/AIDS, was released in 1998 and became one of the new industry’s big hits, with sponsorship from the Federal Ministry of Health and the World Health Organisation (WHO). Its success was another proof that if Nigeria had something to show the world, the world would turn to it.

The spontaneity of it surprised Mokeme. He had done several pilots that didn’t air, and suddenly, with no audition or casting, he was finally onscreen.

Online filmographies of early Nollywood actors are sketchy. In the absence of rigorous journalistic documentation, websites and bloggers and even the actors and filmmakers themselves rely on memory. Mokeme, for instance, is unsure which was his debut screen role: Ejiro’s Goodbye, Tomorrow or a production for Ralph Nwadike whose title he could not remember. The Internet says it’s another 1998 film, Fred Amata’s Rapture. Mokeme laughed: the Internet is wrong; his first was definitely between Ejiro and Nwadike.

Having crossed over from modeling, where he was required to take on different characters for different gigs, it was not difficult for him to navigate the acting demands of the industry.

“I probably had even more experience than people who went straight into action,” he told me. “It was pretty much almost the same thing with television commercials: pretending to be somebody else, dressing up, going on location, being on a set, having a director, reading lines, the same terminology. The difference is just that you’ve been doing it for a 45-second commercial and now you have to do it for a one- or two-hour feature.”

With sudden access to famous actors, and observing them, what surprised him was how much of their presumed success was a paradox.

“There was so much fame but no fortune,” he said. “The moment you come up close and personal, you could really see their struggle. I began to understand why there was so much pushback if you said to your people that you wanted to be an entertainer. I could see people who were my father’s mates, and if they were looking like this here, how were they doing at home? Suddenly, it made sense to me why Alex Usifo did not encourage his models to start acting. The money I made going to work for one day as a model was probably more than their payment for the whole year from working on television.”

It was also a dilemma on a contractual level. A secondary job that did not pay much now required him to come to auditions, then rehearsals, then to shoot for days, weeks. But he could not opt out because he was in love. Despite discouragement from his family and friends, he took up more acting jobs. Sometimes, he had to sneak out of the house to work.

Yet the bulk of productions he was part of, almost 60% of them, according to his estimation, did not pay at all, and the ones that paid did not factor in transportation. He remembered thinking: If this passion is enough to suck me in and keep me here, then I maybe I can forgive the people that I met here.

The conversation had started within the industry, actors wanting to be paid more. “It was up to people like me, who had tasted income, to decide, how do we get this to pay more?” he told me. “Because it’s pretty much the same setting, pretty much the same people who did movies, who rent the same cameras, that did the modeling commercials. So if they’re paying the same fees and cost of production, why were actors not earning as much?”

Soon, A-list actors found a way and upped their fees, and as more actors leveraged their popularity and negotiated better pay, a backlash erupted from the marketers. The marketers had only just grasped the operational protocols of a film industry. Rather than remain buyers, they’d joined the process of production, opening their own studios, importing tapes. And, suddenly, the talent became the obstacle.

To curtail this growing class of pioneering superstars, the marketers deemed them rude and expensive. In September 2004, asserting their power, they created the infamous “G8” list of presumably overcharging actors — Genevieve Nnaji, Omotola Jalade-Ekeinde, Nkem Owoh, Ramsey Nouah, Richard Mofe-Damijo, Emeka Ike, Stella Damasus, and Jim Iyke — and banned them. Message sent, they elevated a new set of actors, who charged much less but, in the new vacuum, rose as the next superstars.

The “G8” ban came one year after Mokeme had a role in the hit film Abuja Connection, although at his level of fame and fees then, he was safe. Abuja Connection starred Eucharia Anunobi and Clarion Chukwura as socialite rivals, and Mokeme’s charm as the fiancé to Chukwura’s character won him more fans. Did he consider it his breakout role? Did more fame benefit his career?

“I didn’t really pay attention to which one was the breakout,” he replied. “It just creeps up on you, you know, it dawns on you, because we didn’t have all these social media to make something trend. It was all organic. There were quite a few of us and the space was large, so whether you were supporting or lead, you ended up in that circle. You started getting media attention, started getting invites to award ceremonies; the entertainment press talking to you, gossip magazines talking about you, looking for a scandal. But the circumstances did not change per se. I couldn’t say, ‘Oh, after this movie now, in my next movie my fee would now triple.’ Because it’s the same marketers that were recycling the films and whoever paid you the previous year was going to do it the next year, and they probably had not even paid at all or finished paying the last one, and if you ask them, you yourself should be paying them for your ‘breakout’ sef.” He laughed. “That” — increased pay — “is what, for me, would have meant a breakout.”

Another problem awaited him. The payoff of his model looks and swagger in Abuja Connection led to a phase where he was typecast as either the playboy or the muscle man. When he tried to ask for something different, directors told him, “Don’t worry, the bodyguard will be a major guy because he will always be there, he will always have something to do.” But all he ever did was escort the lead around, flex muscles, and glare at rivals.

Part of why Nollywood successfully buried itself in the minds of viewers was that it cultivated within the audience an impression of the actors, a brand of character. In other words, the industry needed to typecast actors that it could, until those actors resisted. To force directors’ hands, Mokeme stopped going to the gym. His fashion had netted him the nickname GQ, and now he stopped wearing white T-shirts because they amplified his body, started wearing shirts and trousers, making an effort to look like the characters he actually wanted to play.

He was also rethinking the presumed limitations of typecasting. “I make this argument all the time,” he said to me. “I found that the villain is the character that gives me an opportunity to explore, because the good character, a lot of times, already shares the same moral values with me. But with the bad guy, I get curious. What makes him behave like that? I have to believe him because he believes himself — we are the ones who say he’s a criminal, he doesn’t say he’s a criminal.”

In 2005, Fred Amata cast him in the action thriller Anini, about Lawrence Anini, one of the worst criminals in modern Nigerian history who terrorized Benin City in the ‘80s. He was tasked with playing Monday Osunbor, the right hand and executioner of the gang, a young man of 22 said to have a short temper and a stammer.

By this time, Mokeme had also gone into reality TV, hosting the first two seasons of Gulder Ultimate Search, a wildly popular adventure show then.

given its rupture of the home video system, Nollywood insiders deem the “G8” ban of 2004 the most seminal event in the development of the industry. The actor and director Ramsey Nouah, one of the banned eight, has said that it directly led to the arrival of cinema, which disrupted the power of marketers.

Change had come. It was not only a transition in distribution, it was an upgrade in filmmaking ethos and equipment. As the quality of production improved, observers sought to demarcate the industry into phases, coining the terms “Old Nollywood,” for the home video era, and “New Nollywood,” for the cinema era. In welcoming the new, critics derided the former phase as broadly lacking in quality. They were, it seemed, in such hurry to dispel its ghost that they appeared to dismiss its strides.

For veterans like Mokeme, who nurtured the industry and carried it on their backs from the 1990s into the 2010s, it would have been easy to feel that the work of their generation was in danger of being buried. Did he ever feel that way?

“No,” he replied. “I’ve never subscribed to the terms ‘Old Nollywood’ and ‘New Nollywood’ because the industry is ever-evolving, you know. I mean, where we are today as an industry in Nigeria, where the world is in film, would not have been possible without the people who did the silent movies. But if you [didn’t know and] watch the silent movies today, you’re gonna say, what are these guys doing?”

He continued. “Technologically, the industry has gone through different phases, you know. We had the phase when we were using pneumatic cameras, we had the phase when we were using the first set of PW 100 cameras. It’s only that we were a little late in catching up, you know, and, I mean, that is understandable because it was largely privately funded by people who didn’t understand what the industry was about. They just needed to make money, so they came in.”

The so-called New Nollywood were people inspired by Old Nollywood, he pointed out. “They only came in when they started seeing the success. And some were actors who were probably playing the waka pass or extra roles, and as soon as they got elevated to play some major characters, then they became ‘New Nollywood.’ That’s not how it works. People grow. New people, new actors, will always come in. Hollywood has been there for how many years, over 100 years? It’s not the same actors that are there. Will you call the other ones ‘Old Hollywood’ and this one ‘New Hollywood’?”

Yet the aspirations of New Nollywood were evident and being tested, and pairing its funded ambitions and branded visibility with the unmaximized talents of Old Nollywood proved to be a goldmine. For some in the latter group, the improvement in production was a chance to reintroduce themselves to a younger audience. But for the ambitious ones like Mokeme, it was more: an opportunity to make a defining contribution.

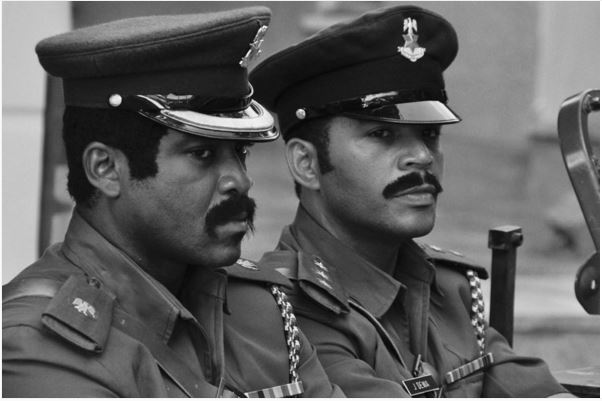

In 2013, he received the script for Izu Ojukwu’s ’76. It was about a young captain accused of being part of a coup, told from the perspectives of him and his pregnant wife. The story is set in 1976, six years after the Biafran War, a time of palpable tension in the Nigerian military. He was to play a major, Gomos, whose job was to extract a confession from the captain. It was a small supporting role, but, for him, it was substantial.

Every time Mokeme opens a script, he scans the character for authenticity. He prides himself in working differently from most of his colleagues. His inspirations are Denzel Washington and Al Pacino, and every time he watches Washington, he sees a calmness that the American actor brings, like he is not so much acting as simply being the character.

As Mokeme reads scripts, he visualizes. As his excitement shoots up or down, he decides whether or not to commit. Because of this, he does not hop between projects; he spaces them out so that he can be true to the character. He knows that part of why many Nollywood films are badly made is that most people do not come to set with this mindset, and he finds himself having to compromise on quality. He wishes for productions where these components would be taken care of, which would make it easier to show how much work he had put into the character.

So when Ojukwu contacted him for this period film set in the ‘70s, he wanted to confirm that the team had what it took — costumes, props, locations, a committed investor — to deliver the script. They did. He was surprised that Ojukwu even planned to shoot on film, on celluloid.

He dove in, accustomed himself to the dressing and look. This was Nigeria, 16 years after Independence, so he went to YouTube and studied how the statesmen and heads of state spoke. He watched everyone from Nnamdi Azikiwe and Tafawa Balewa to Obafemi Awolowo and Olusegun Obasanjo.

“A project like ‘76 requires you to really dig deep,” he said. “Remember, back in the day, we didn’t have all of the slangs, a lot of the bastardized English we have now. Nigeria was pretty much just transitioning, you know, and still trying to get our feet together, and most of the elites had British education. Their English was pretty much a blend with their Nigerian accent, people trying to acclimatize and bridge. They had a totally different orientation.”

At the Ibadan Barracks, where the film was shot, the cast often gathered to discuss the story. With his peers Ramsey Nouah and Rita Dominic as leads Captain Dewa and his wife Susie, and an ambitious director, Ojukwu, at the helm, Mokeme felt, as he put it, “my creative juices boiling.” As Major Gomos, he brought intensity to his scenes with Nouah’s Captain Dewa. As a soldier committed to duty, the prospect of disloyalty was aggravating, and he pursued a confession with determination.

’76 was the first time that many people began to reassess Mokeme’s work. And it was in the heat of the acclaim that he felt the weakening on the left side of his face and looked into the mirror and saw that he had what doctors would tell him was Bell’s Palsy. He had reached a new level in his career only to learn that he may never act again.

And so, weeping bitterly, Mokeme knelt down in his hotel room in Abuja and made his deal with God: If You put me right back in a position where I can go back to doing this thing that I really want to do, I will bring this talent to You in such a way that even You have not seen before. Amen.

The curtains were drawn, the bulbs were bright, and he got up to go down for lunch. A hoodie and dark shades so he wouldn’t be recognized. But stepping out of the elevator, the first person he saw was his longtime colleague, the actress Ini Edo.

“Oh, Chidi, where have you been?” she asked. “We’ve been talking about you. Look, I think there is something that we are going to do, and the way you’re looking now, you look like you just jumped out of the page of that script!”

Edo had a story in development, with her as executive producer and female lead, and they had been talking about Mokeme because they had considered many actors and were not convinced. They’d even gone outside the industry and contacted musicians, seeking a similar rugged spark to what the rapper Reminisce brought to King of Boys. Yet all the auditions were unsatisfactory.

Although he was keeping away from acting, due to his face, Mokeme said he was interested and Edo said she would get back to him.

Then came the pandemic.

Then in 2021, the world back to normal, and Mokeme having forgotten their conversation, Edo called again. “G., how far? Are you back to working?” she asked. “Remember we discussed one project that time?”

“What’s happening?” He was still interested, even though he was still waiting for his face to heal.

“I just want you to see the script first,” she said. She sent it. He was dressing up to step out and she called again. “I just sent it on WhatsApp. Check it.”

“I’ll check it out,” he said.

Minutes later, she called again. “Have you seen it?”

“I haven’t seen it. I’m trying to go somewhere. I’ll see it later.”

“Please, please, just open it.” Edo sounded excited.

Mokeme opened the first page and began reading. It was a TV series. He sat down. By page three, he took off his shirt. It was 4 a.m. when he finished reading and he called Edo. “Are you guys ready for this story?” he asked her.

She said yes.

“Let’s go and do it,” he said.

Mokeme laughed as he recounted the story to me. “Because I was reading it, it was like everything was coming together at the same time, you know. You can see that dream. Your spirit is agreeing. The universe is agreeing. My visuals were exactly where I wanted them to be. Because I’ve been in the industry for so long, I’ve seen so many stories that, when you come on set, you see that what they advertised to you as the nuclear bomb — what they will bring instead, if you get matches, you will be lucky, they’ll just bring broomsticks!” He laughed. “I could see what the script needed because the writers had gone crazy.”

Edo told him that the actor Richard Mofe-Damijo had signed on in a supporting role, and that the project would be helmed by Dimeji Ajibola, a director new to the scene. He did not know who Ajibola was. He checked out his film Ratnik, a sci-fi thriller set in a remote African town in the early days of World War III. He thought to himself: Boys are coming up.

He knew instantly.

This script, Shanty Town, this violent story of a community of women terrorized by one man — this was the answer to his prayer. The leading male role was his, a psychological and physical showcase unlike any other he had seen in Nollywood. God, he felt, had done His part. Now it was time for him to do his.

“When do you guys want to shoot?” he asked Edo.

“May,” she said.

“Can you push till June?” he asked her. “Let me go and cook this character.”

She agreed.

He got on a plane, to America.

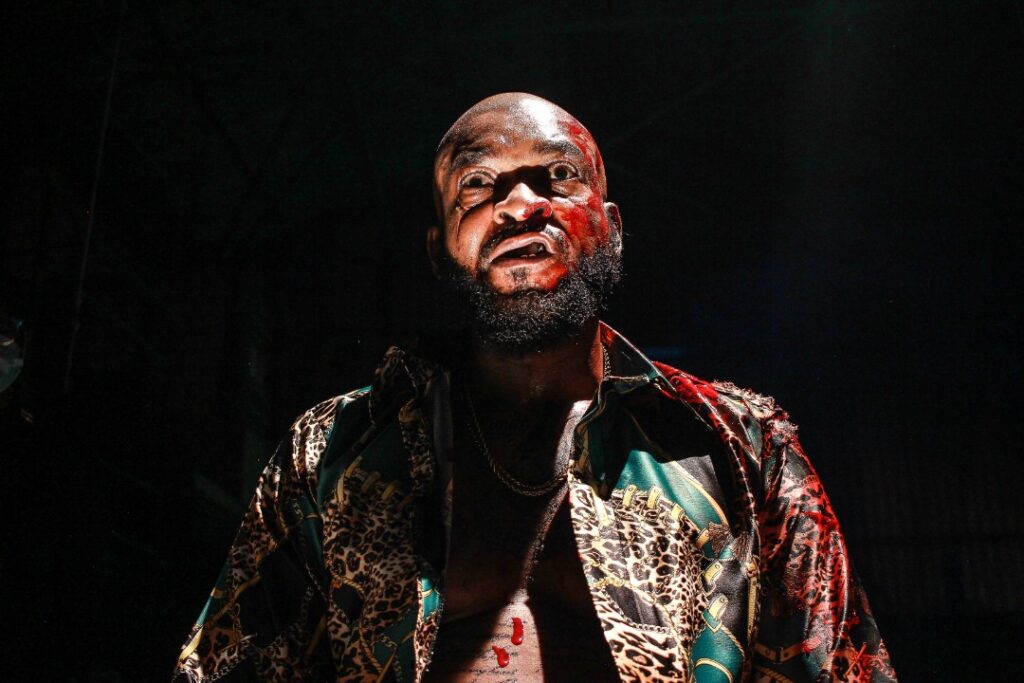

When we first meet Scar in Shanty Town, he is not played by Mokeme: he is a teenage militant carrying a gun on a boat. Eighteen years later, he is fully grown, and he is sitting in a shadily lighted apartment, surrounded by young gang men playing games, a girl kneeling between his legs, giving him head. He is their leader, with the facial scar to show for it, and they come from the titular Shanty Town, a slum Lagos community where he runs a ring of sex workers.

The people of the community cheer for him on his return, but we soon find that the women working with him loathe him. One of them, the determined Jackie (Mercy Eke), has just bought her freedom. “For all your services to Shanty Town,” Scar tells her, handing her an envelope. But not before pressing her breasts with the most casually deliberate intention.

A frightening side of him comes when the next girl, the persistent Shalewa (Nancy Isime), tries to buy her own freedom. Scar gets a calculator and adds up what she is “owing” him: N3,000 daily feeding x 365 days x 3 years; five abortions; one syphilis and one gonorrhea treatment; security; spiritual protection: it amounts to N15 million. Mokeme imbues Scar with a potency of terror as he adds these up, and even though we haven’t yet seen him be violent, we see, from Shalewa’s dread, his capacity to inflict harm.

One survivor of his menace is Inem (Ini Edo), who returns to Shanty Town after three years in jail — left there by Scar. Inem is vengeful: Scar owes her and must pay. But her friend, the resolute Enewan (Nse Ikpe-Etim), has taken her place in Scar’s establishment and, unknown to her, his bed. Enewan helps in his dirty work, ensuring that the girls “settle” Scar with 60% of their sex work earnings. A conversation between the two women further inform the viewer of the power that Scar wields over their lives.

But Scar is not all powerful. His godfather, Chief Fernandez (Richard Mofe-Damijo), has all the real power. “I worship you, Father,” Scar prostrates, kneels, kisses his ring. And as if to strip him of all his layers, Chief calls him by his real name: Aboderin. Chief, already owner of one-tenth of Lagos State, wants to be the next governor, and Scar is too happy to remain his underground muscle — until Chief makes a demand to shut down one of their key operations. It may be where Scar garners his relevance but Chief does not want that dirt trail back to him. And herein lies all the difference between the men. When Chief paraphrases The Gutenberg Galaxy — “The world is a global village and the skills to rule the village is that of a hunter or a fisherman” — it is clear that, even as Chief expands his purview, he limits Scar’s place to the village of things.

Shanty Town is about Scar’s conflicts: with Chief, with the women of his community, and, in a glimpse, with his person. The last one pokes out when he is kidnapped by the deputy governor Dame Dabota (Shaffy Bello), Chief’s rival in the gubernatorial election. Blindfolded, Scar explodes when he hears her voice: his main anger is not that he has been kidnapped but that it has been done by a woman. How could he control the women in his community and, outside it now, be controlled by one? “I will put my dick in your ass and it will come out of your mouth, I will show you who Scar is!” he thunders. Unmasked and seeing it is the dame, he apologizes profusely. Dame Dabota knows it: Scar is not smart; his superpower is his will to violence, not to outsmart enemies but to overpower them, so she plays that against him and wins him to her side.

Mokeme drags us into Scar’s head by putting all his complexity on display. He uses his body and voice to degrees of exposition, piecing the character together as we watch, making acting choices that are not only surprising but that enhance our understanding of him. Alone in his office, he pulls out a cloth from his crotch and casually sniffs it. It is not merely that he objectifies women; it is the way that he does it. He stares at Shalewa’s ass and says in delight: “Ike e ji ama-atu.” Exemplary ass. It is not merely that he knows when he is outmatched; it is the way that he resents being powerless. When he is beaten by Chief’s bodyguard, he glares at the bodyguard in a way that makes us realize that his resentment is, really, for Chief.

His fearsome, menacing presentation, his recklessness, his violence: they are not random; they comes from his need to own, to control, to fill an emptiness in himself, perhaps a lack of self-worth — the kind that sees him act like a dog with Chief and Dame Dabota, who treat him as intellectually deficient but organizationally useful. He asks Dame Dabota what Chief did to her and she replies: “That information is above your paygrade and above your capacity to fathom.”

“Scar is mentally and psychologically distraught,” Mokeme told me. “He has learned to survive from an early age. He’s learned to survive by himself. He’s got his own inferiority complex but he’s a survivor, so he has found how to manipulate his way between layers of society. So you see how he can go from the zanga to Banana Island. He’s balancing this and finding his place there.”

Scar’s ruthlessness and selective softness both show when he accuses his crew of stealing from him. As they stand before him, defending themselves, he pulls a gun and shoots up suddenly, frightening them. It is a little demonstration of casual terrorism. He kills the accused man and orders everyone out, except Inem. He offers her a drink. Hot or cold?

“Drink? With you?” Inem is shocked. “You were just going to kill me.”

“But you no kpai na,” he replies. “If Scar wan kill you, you go die.”

When he asks her to return to Chief, who had brutalized and raped her, she cries, begs not to go, and his response is to remind her that he saved her life, that, in other words, he might now decide what to do with it.

“Even when out of control, Scar is always in control,” Mokeme said, “because everything must be playing towards his agenda. He’s not about to reason with you. He does not want you to give him an alternative. He gets his mojo from this manipulation. Everybody is dispensable. You’re only relevant if your agenda is working with Scar’s agenda.”

Yet that scene with Inem, that juggle of blind rage and awake love, also makes you wonder if Scar, finally, is redeemable — redemption being relative — if experiencing real love could have pulled a character like him back from implosion. (It makes sense because he is constantly aware of love. “Family is forever,” he tells one of his women, and then hacks her to death.) In showing different sides of Scar in different scenarios, one wonders the dominant emotion that Mokeme drew from: anger, fear, shame?

“My main thing was, in every scene, to draw a motivation that stays true to his back story,” he replied. “So if you watch the brutalization, it was a direct consequence of everybody trying to make him feel useless and inferior. He’s just coming from Chief, who is saying to him that his kingdom — that he is going to shut it down. Tie that to Jackie, who, by deciding that she doesn’t want to be part of the zanga again, is also telling him that there’s nothing here in Shanty Town, right after she has motivated Shalewa to come and make the same move. Things are disintegrating right before his very eyes, you know, so you see how his character arc is changing with every new event. His association with the deputy governor shines a light on the possibility of him getting a kingdom back, and that’s all that matters to Scar. A kingdom is where he’s able to assert authority.”

Part of Scar’s puzzlement that the women under him are not grateful that they owe him their lives comes from his having been rejected in many ways by the people he felt should have cared for him, chief among them Chief Fernandez, his biological father. He views Chief’s legitimate son, Femi, as a usurper.

“See his reaction to that bodyguard?” Mokeme said. “He’s like, Look at you, you don’t know that I am the owner of the throne here. Can you do that to the Prince? So he gives Chief that look that says, You are standing here and this dog of yours is beating your son. So everybody is in the same book for him. You see the venom with which he sides with the deputy governor, you can see the anger.”

There is a way that Scar could be seen as a shard of broken masculinity. But this is not to say that there is a psychological deconstruction going on. Shanty Town has too much action and buildup and limited time for him to be a character study like Sola Sobowale’s Eniola Salami in the King of Boys film and TV series. The other man you can compare his dedicated villainy to, Ramsey Nouah’s Richard Williams in Living in Bondage: Breaking Free, has a less cluttered purpose: he wants power for power’s sake. Scar wants power to feel less empty.

Although the script and direction do enough to create visual statements of Scar’s power — the ominous dark-hued lighting, that bathing scene with girls — it is how Mokeme gives him the relentlessness of Old Nollywood villains and plays it up with devouring detail that makes him come alive. It is a domineering leading turn unlike any other we have seen in Nollywood, one of those rare cases in the industry where, because the actor communicates with immediacy, the performance lifts the character.

When Shanty Town streamed on Netflix in January, it trended for weeks, much of the praise lavished on Mokeme, many viewers having only just woken up to his talent. His nomination for Best Drama Actor at the AMVCAs was expected, as was a win. (This interview was done two days before the AMVCAs’ May 20 ceremony.) But on a night when Old Nollywood ceded ground to New Nollywood, in perhaps the awards’ biggest upset ever, he lost to Tobi Bakre in Brotherhood, sparking a backlash.

How the best screen performance in years lost to a regular, if energetic, turn in an action film brought the overdue question of why the show opens a technical award to voters, reducing a celebration of craft to a popularity contest. For me, the more disturbing concern is that the industry’s trendiest award is fan-voted, and that the prestigious, peer-voted show, the Africa Movie Academy Awards (AMAAs), is open only to films and not TV series, making Shanty Town ineligible.

It did not matter, though. What mattered was that, after decades as a supporting player, Mokeme had finally, at 50, staked his claim as one of the industry’s handful of exacting actors, one of the few around whose necks, awards or not, you could garland the words: “one of the best.”

Before shooting Shanty Town, Mokeme did an indie film called Pillars of Africa. The drama, which also had Hakeem Kae Kazeem and Sola Sobowale, fetched him the Best Actor in an Independent Film prize at the Hollywood and African Prestigious Awards. He later appeared in The Therapist, with Rita Dominic and Michelle Dede, and a Cameroonian film Half-Heaven, and has upcoming roles in the Merry Men film series and in Tokunbo, directed by Nouah. But he has, in the last few years, been looking beyond acting, into directing.

Unlike a few of his peers, like Genevieve Nnaji and Funke Akindele, who transitioned directly from acting, Mokeme has been working behind the camera for some time now, as a special effects director. His production company, Mad House Studios, had worked on a series of early industry classics: Ijele, Igodo, Izaga, and Ikoro, among them. His years behind the camera brought him to his first directorial feature, Bamboozler, released last year.

Set in Dallas, Texas, Bamboozler is the story of a woman whose need for love leads her to a maniac and serial killer. The neo-noir suspense thriller, described by Mokeme in 2021 as “a hybrid of thriller, romance, and softcore,” was written by Franklin Tochi Nwosu (District 14) and developed by Begoty Media. It is the first on a directorial and producing slate of three for Mokeme. A second feature, set in Atlanta, Georgia, is reportedly in pre-production.

“I’ve always thought that was going to be the end play, you know, producing, directing, because that’s how you grow,” he said. “You go from being an actor to taking more control. You’re no longer really dependent on just people calling you. You now make things happen either for yourself or for other people.”

There are scripts that have been on his table for almost 20 years but that there hadn’t been financing for. “The industry was not ready,” he said, “because, in spite of your dream and your vision, somebody’s going to get their money back. And if you can’t guarantee that that budget was going to come back, then that dream or vision don’t mean nothing. It doesn’t fulfill the passion of the investor. And that was a big setback for me. People in the industry were into quick money. In fact, we went from me complaining that we didn’t do rehearsals anymore and that they used to rush productions, to people competing for who used to spend the less time making the movie.”

“Really?” I ask.

“Oh, yeah. People were competing for who saves budget by spending the least time. At some point somebody even had the record for making a movie in two days.”

We laughed.

“I don’t want to shake any tables,” he chuckled. “And I always had the reputation in the industry where they always say, ‘Leave GQ, he’s not with us, he’s just passing by.’ And that’s because, you know, the way I came in.”

He explained. “The advertisement industry was very professional, so when you go on their sets, you don’t play around. Most of the companies and production houses were even controlled by expatriates. So there was a difference when you moved to the movies, where they were just starting off. Most of the practitioners were new, and because I came from a different level of professionalism, the quality of the product that I was going to put out was very important to me, and I didn’t feel like I had all of the indices to make it happen.”

The lack of resources and the slow growth of professional culture are why he is impressed by two of his directors who surmounted the constraints: Izu Ojukwu and Dimeji Ajibola. “I love how Ajibola thinks. I love the way he processes. I love his shooting protocol.” Most actors failed on Ojukwu’s sets because he insists on getting quality, he added: “Most other directors will take what you give them as long as they were working, but Izu was not going to cut any corners, he was going to take his time, he was going to make requirements, and the result is always phenomenal. If you were not prepared to give him what he needed to bring the story to life, he will pass. He was my No. 1.”

At this stage in Mokeme’s life, everything has come full circle: his early career ambitions and his current ones have finally aligned. He remembers watching Bollywood and Chinese films back then and wishing that all of his colleagues would see where the industry was going, what it could become.

“Even while you’re doing your home videos, you’re still secretly wishing that these guys would get to a place where they’re doing the things properly,” he recalled. “And it’s taken all this time for us to come right back, because all of the things that I used to say to the marketers back in the day, that, ‘Look, people are going to come from nowhere and hijack this industry after you have put in all these sacrifices, and the reason they’re going to is because you guys are not adapting with your growth. The industry you are building is the same as Bollywood, the same as Hollywood, but you have to see it like that to run it like that. You guys are running it like a shop. You’re making money and you are not seeing the industry, and that has cost Nollywood dearly.’”

His prediction came to pass. “Because now that all the sacrifices have been made, the people who see an industry have come in and they’re calling the shots. They were not there when the industry was being grown, they played no part in building it; they just understand that this industry needs a certain kind of structure.”

He is elated at the new respect for professionalism. “I think the more we begin to give in to professionalism, the more other people will be forced to either quickly adapt and do the work or fall by the wayside, you know. But we must reward professionalism. Everybody now wants to work with Dimeji Ajibola. You see how Jade Osiberu has gotten her flowers for a good job? You see how Kemi Adetiba has gotten her flowers? We are beginning to separate the wheat from the chaff.”

Mokeme believes that Nollywood will become global like Afrobeats. All the industry need to do is develop structure and talent to prevent it being exploited. There is passion in his words, and I sense that it is only the pioneers who built it, people like himself, who can truly understand how far Nollywood has really come.

Back in the ‘90s, he would attend social functions, and, in front of him, parents would warn their children not to be like him, because, by becoming an actor, he had shown that he had no plan for himself.

Now he laughed with relief. “I always say that one of the best things that has happened to me as an actor is that I have gone from that person that they used to say, ‘I don’t want to see you, wait,’ to the guy who the President says, ‘You must come to the house, Chidi, because my son wants to read filmmaking.’” He is referring to former president Goodluck Jonathan, who offered an industry built on private equity and sweat its first taste of government support through the reported N3 billion Project Nollywood. (The project has since generated controversy.) “He hardly went anywhere without inviting an actor to go with him, you know,” Mokeme said. “Anywhere in the world. So that means we had gotten credibility. That’s a lot of progress, you know.”

In January, days after Shanty Town was released, Mokeme told Rubbin’ Minds host Ebuka Obi-Uchendu that the reception humbled him. “From where I am coming from in the last four, five years, I am still trying to take it in,” he said. “There’s been a hunger. I could see things happening, and there was nothing I could do about it.” The hunger is still there, but now he is putting it to use.

When he looks back like this, from his start as a model through his Bell’s Palsy, only one word comes to his mind. “Divine,” he said. “The whole journey is divine.” And then he goes on Netflix and sees Shanty Town still ranking high, and he goes on Prime Video and sees the new films, and he sees all the inflow to Nollywood, and all he can think is: Man, we built this. ♦

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

No One Covers Nollywood, African Literature, & Culture Like Open Country Mag

— Cover Story, March 2023: Rita Dominic‘s Visions of Character

— Cover Story, December 2022: Chinelo Okparanta, Gentle Defier

— Cover Story, April 2022: The Next Generation of African Literature

— Cover Story, February 2022: The Methods of Damon Galgut

— Cover Story, September 2021: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is in a Different Place Now

— Cover Story, July 2021: How Teju Cole Opened a New Path in African Literature

— Cover Story, January 2021: With Novels & Images, Maaza Mengiste Is Reframing Ethiopian History

— Cover Story, December 2020: How Tsitsi Dangarembga, with Her Trilogy of Zimbabwe, Overcame

— Awaiting Trial: Families of SARS Victims Speak in Devastating Documentary

— The Making of Mami Wata, Nigeria’s First Film to Premiere at Sundance

— How Dakore Egbuson and Tony Okungbowa Traverse Trauma in YE!

— Writing Omo Ghetto: The Saga, Nollywood’s Highest Grossing Film of All-Time

— Country Love Depicts Tenderness in LGBTQ Lives

One Response

You write very well, captivating the reader. This article made me feel like ive gotten to know Mokeme better, like he chatted with me directly and we’re now friends. I’ve also got a better understanding of the Nigerian movie industry. Kudos for a well written article!