The title of “greatest living writer” has often been implied in Western literary media for decades, parameters changing depending on the recipient, a signifier of what narratives are deemed “representative” by Eurocentric standards. Over the centuries, it would have been William Shakespeare, and later Charles Dickens, and later Leo Tolstoy. In the 20th century came Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway. Then James Baldwin, who lifted his voice into activism and received no major awards, and V.S. Naipaul, who did receive that title.

As time allowed more recognition for non-White writers, the Black ones found themselves shouldering cultural and political duties that their peers did not have to shoulder. Then towered Chinua Achebe, who conveyed the restive spirit of a continent, a titanic scale of impact approached only perhaps by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. In the West rose Saul Bellow and Philip Roth. Eventually, the title arrived at another rightful doorstep: Toni Morrison. But almost all those pioneers of modern Black literatures had passed on, except one.

For 70 years, Wole Soyinka has been thinking and writing in every genre: drama, poetry, fiction, nonfiction, essays; and in other literary categories: editing and translation; even branching into other arts: singing and acting. He had been living what he created, putting his body on the line like no other, and was still affecting the cultural and political life of his nation in a way that few in literary history ever have. His Nobel was the Literature Prize but could easily have been the Peace Prize. By any standards, it was him. Wole Soyinka is the greatest living writer and has been for some time now. Yet, at 91, at the dusk of a life full of controversies, he is embroiled in his most threatening one yet, at home, in Nigeria.

Mr. Soyinka — in person and on email, I call him “Papa” — first agreed to come to Open Country Mag four years ago, in mid-2021, even before our first anniversary. We had only just published three cover stories then — on Tsitsi Dangarembga, Maaza Mengiste, and Teju Cole — and were prepping our fourth, on Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Imagine my joyous shock, my gratitude, which deepened when he told me that people frequently sent him links from Open Country Mag, that it was “always a stimulating read.” Yet if this cover story had come out then, it would have been different, no less monumental but narrower in scope, focused on literature. As is, it deals equally with politics.

When I told a Nigerian friend that this was happening, she replied, “My dear, there’s nothing you can do for his legacy. People have tried.” She was referring to his interviews since the rigged 2023 presidential elections, in which he criticized the Labour Party candidate Peter Obi, a man whose clean reputation and plans for ambitious economic revival rallied young Nigerians to him, while having no negative word about his opponent, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu, who leveraged ethnic and religious divisions during his campaign and faced allegations of crime. My friend’s response was indicative of the rage of many Nigerians, their sense of betrayal. Had he become, they ask, the kind of elite Nigerian that he himself railed against?

Much of the fury has been unleashed on social media, with Mr. Soyinka fighting back. The experience, he told me, has been “so profoundly earth-shaking that I prefer not to talk about it.” But he did talk about it. And even as our respective political positions are far, far apart, even as I communicated that, even as I am three generations of literature and six full decades of life behind him, I have now a sense of what the emotional stakes are for him, how time and place shape emotions and generational differences.

And yet every generation must face its own problem, face it how it deems fit. This is one story of how Mr. Soyinka’s generation fought. It is also one template of how we, today’s young Nigerians, fight. And the arc of new confrontations — literary and political, in the 1960s and today — is one of several major concerns of this story.

“There are enormous problems that these interviews solve,” he said at the end of our meeting, “and when people try to block an access to transformative processes, they’re doing a great disservice to the totality of what we call a nation, something very fundamental in the makeup of any community. Because one thing which I’ve always stood for is the right for the expression of opinion.”

(I imagine that most readers might be interested only in our conversation on current politics, and they can find it in Parts II and V.)

Soyinka declined to read a draft of this story (his humourous email: Your wahala, not mine!), but he did express concern for me. I was getting myself in trouble, he suggested on three separate occasions. He meant that the very act of me publishing a story on him was dangerous for me.

“Okay oh, you’ll see even what we talked about,” he said, “you’ll see how the kind of people we are talking about, how they’re going to, before they read the first sentence and made sense of it, they’re already commenting.”

What I left out in my response to him was that, as aggressively invested as I am in the political, my task here is the preservation of literary heritage. Politics was not why I wanted this interview. It was literature, art, the thinking behind his craft. But while I wanted at first to write only about those, the compelling story lay elsewhere. In finally fusing them, I had to ensure that the heat of politics did not eclipse a ginormous artistic achievement. I had to discern pure art from pure politics, to track where they clash, where the latter has fed the former, but ultimately to conserve art.

My pursuit of this interview over four years, my finally writing this Profile, is a small victory against a long history that sidelined the contributions of African and Black writers in the global conversation, that erased models of achievement for my own generation, sometimes by transposing them to Western publications. This is why I started Open Country Mag, to tell our stories that would never appear elsewhere, in ways that no one elsewhere would consider.

He is the second titan in his 90s that I have profiled — the first was Francis Cardinal Arinze, last year, now 93 — and I am acutely aware that time is running out to get the stories of their 1930s pioneering postcolonial generation. Their deliberations were prescient, a result of sustained thinking, and we need that now more than ever. In fact, it was on the day that Ngugi wa Thiong’o died that I emailed Mr. Soyinka, to reopen conversation about this Profile.

So what I did not tell him then is what I would tell anyone: We have no time. But make no mistake: this is neither a disclaimer nor deflection: it is context — one that would make full sense when one reads the story. Little more need be said about it here, outside the link soon to appear below.

Unlike most of our cover stars, there are multiple serious Profiles of Mr. Soyinka in existence, many of them available online, few of them declarative in a major way, and so the challenge of writing yet another one was to not simply produce an annotated summary, a highlights reel; it was to understand him, to see him and to put his intellectual essence on paper, his spirit and motivation. I was determined to read everything he has ever published, but the breath-taking breadth of his work almost rendered this story unconcluded.

It was a practical limitation. We agreed to the interview in June and met in August and I had until December to get through the selected 20 or so books on my shelves, not to mention countless Internet articles by journalists and academics from the 1960s to the ‘80s. And he is often not an easy read. In his memoirs, his narration is scattered, and piecing timelines is tricky. (Future biographers may find something useful here). Too much context meant that I did not reach out to anyone for comments. The primary words are his and mine, what he has said over the last half century and what I make of it from my vantage.

I sought to locate him during three formative phases of his life: the 1960s when he was in his 30s, as newly independent Nigeria fumbled Africa’s hope and the continent’s writers tried to build something new; the 1990s when he was in his 60s, in the final decade of military dictatorship, fleeing his country; and the 2020s when he is in his 90s, as he faces this new clash with many Nigerians, most of them young, who disagree with his political views and have sought to de-canonize him.

Each of the six sections — “The Road,” “The Wound,” “The Fire,” “The Stage,” “The Crossroads,” and “The Bush” — puts him in a physical and mental place. Each shows him as, simultaneously, a thinker, a doer, and a feeler. Above all, I gave space to some of his most important ideas. It is an impossible task to balance these on-page concerns with real off-page ramifications: just impossible within the remit of a Profile.

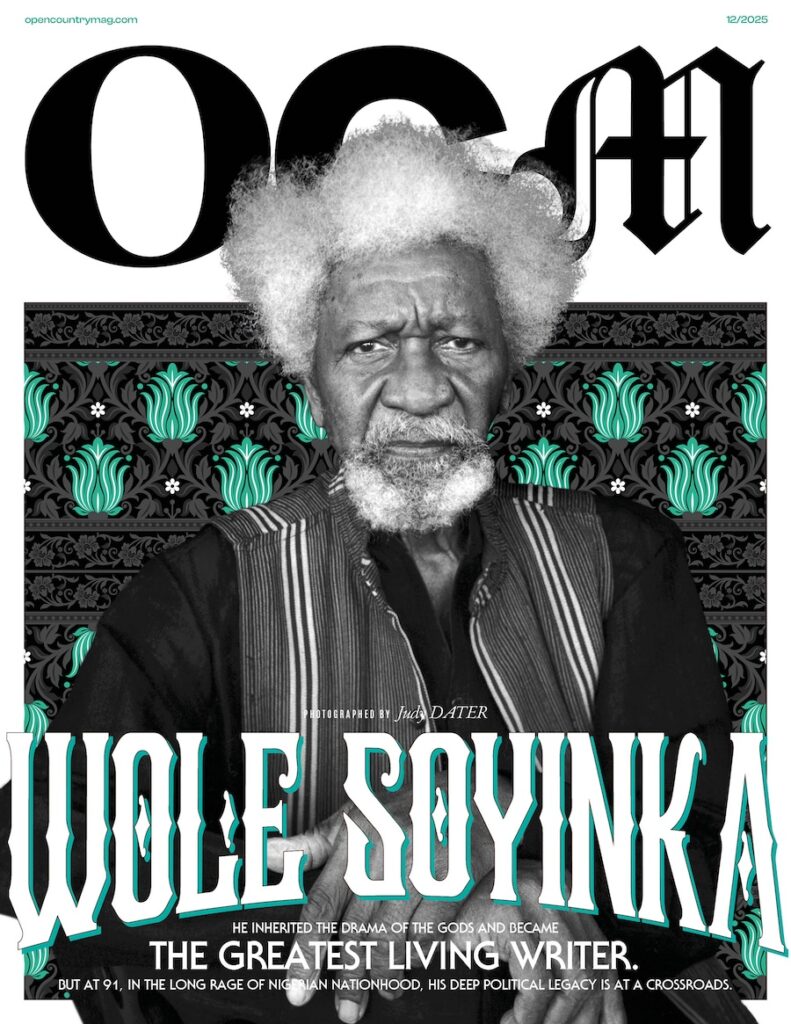

This is Open Country Mag’s 12th cover after those on Ms. Dangarembga, Ms. Mengiste, Mr. Cole, Ms. Adichie, Damon Galgut, The Next Generation special issue, Rita Dominic, Chinelo Okparanta, Leila Aboulela, Cardinal Arinze, and, last month, Chude Jideonwo. All these covers bear the magic of our gifted Art Director and Lead Product Designer Emeka Ugwu. This one comes on our fifth anniversary as a magazine.

The portrait of Mr. Soyinka on the cover was given us by the iconic Judy Dater, whose famous unobjectifying compositions — in her Imogen and Twinka at Yosemite, her Self-Portraiture sequence, her My Hands, Death Valley, among others — helped keep American photography responsive to the feminist movement. Ms. Dater has been called “a photographer’s photographer,” and this one was shot as part of her 2024 series on Black thought leaders, titled Poets, Prophets and Pioneers. It is the rare image that captures the authority, regality, and gravity of Soyinka, and I doubt there is a better one in existence. Ms. Dater honours us and has my eternal gratitude.

This is the best interview I’ve done, and in a way, I feel that my job is done, or that it may now be really starting. It is Open Country Mag‘s fifth anniversary and I feel that I just completed a cycle. I cannot explain what it means to me that I was privileged to encounter the greatest living writer, one of the creators of what we do, and disagreed politically with him and he replied with such frankness and involvement. I was still processing that privilege when he said, “Normally, it’s other people who ask for photographs,” and directed me to get someone to photograph us. It is the professional honour of my life.

A final thing: since becoming a writer, I have devoted these 13 years to reading and thinking and the exhaustion of fury, but few books have taught me as much as Myth, Literature and the African World, Soyinka’s 1973 effort to create an African basis for literary creativity. I hope that every African writer, and artist generally, reads it and sees what we have sidelined, what we could incorporate. ♦

Read: “How Wole Soyinka Inherited the Drama of the Gods — and Shadowed the Nigerian Tragedy.”

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

Previous Cover Announcements

— Chude Jideonwo Is on the November 2025 Cover of Open Country Mag

— Francis Cardinal Arinze Is on the August 2024 Cover of Open Country Mag

— Leila Aboulela Is on the December 2023 Cover of Open Country Mag

— Rita Dominic Is on the March 2023 Cover of Open Country Mag

— Chinelo Okparanta Is on the December 2022 Cover of Open Country Mag

— The Next Generation of African Literature Is on the April 2022 Cover of Open Country Mag

— Damon Galgut Is on the February 2022 Cover of Open Country Mag

— Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is on the September 2021 Cover of Open Country Mag

— Teju Cole Is on the July 2021 Cover of Open Country Mag

— Maaza Mengiste Is on the January 2021 Cover of Open Country Mag

— Tsitsi Dangarembga Is on the December 2020 Cover of Open Country Mag

One Response

That countryman Wole Soyinka is the greatest living writer is beyond a shadow of a doubt. The sheer breadth and genius of his writing is unmatched. However, in all honesty, I believe he owes young Nigerians especially those who look up to him an apology. His criticism of Peter Obi amounted to political rascality.

Thank you Open Country Mag for enriching lives through thought-provoking, inspiring, and transformative pieces like this one.