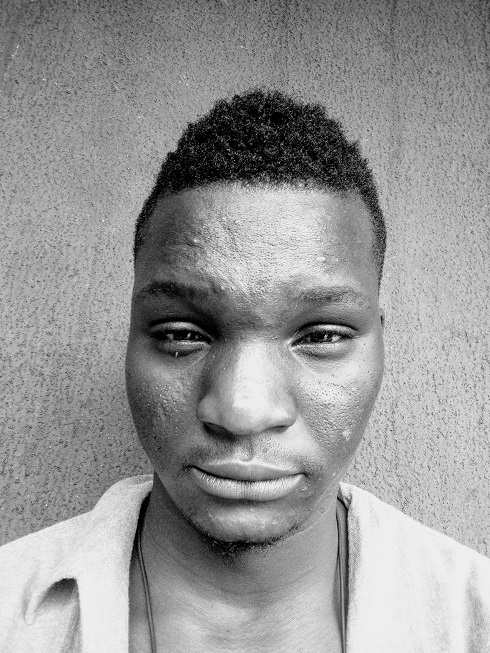

Chrysanthemums for Wide-eyed Ghosts, the debut collection by the Nigerian poet Echezonachukwu Nduka, strolls through the grey park of existence—life and death, grief and joy, exploring the natures of people, places, and things. His new collection Waterman is as evocative, taking the reader on a spiraling journey. It’s a sobering one, full of humility and restrained passion. It isn’t surprising how frequently Nduka, a pianist, references classical music in his poetry.

In Waterman are large ideas, going in sparse movements. They demand attention—no, they request it. I found Nduka a worthy witness to pain; given the raw vigor of mourning, it’s remarkable how detached yet personal he can be, how meditative, too. In rare moments, he allows a personal lash at oppressive systems and philosophical injuries, and catharsis best describes the warmth of such poems. But mostly, the poems unwrap coolly.

His journey homewards to the Southeast of Nigeria is a highlight. “On The Niger” is a look at the iconic bridge connecting Asaba, in the old Midwest, and Onitsha, the bubbling market city in the East:

Onitsha craves to flow with the currents of the Niger, hears her silent pleas and thunderous fury,

The deep secrets of her journey northwards—sounds of pearls cast from her depths to markets and stalls,

And watches her graceful dance to the rhythm of drums.

Upper Iweka sits on the surface of bustling harmonies,

Traders compete with chorus of profits. But homeward students in multicolor uniforms sing that water,

Even the Niger— does not wash away the horrors of history.

Nduka invokes paradox: with “bustling harmonies,” he bears testament to an effervescent spirit, but with “the horrors of history,” he speaks of the pogrom of 1967-70, when an internationally-backed Nigerian government suppressed Igbo lives and possessions, destroying the secessionist Republic of Biafra.

Among Biafran soldiers who died during the war was the poet Christopher Okigbo. A spiritually-inclined man fond of water, Okigbo’s mysticism inspires Nduka, whose lines contain words like “pearls” and “secrets.” Like Okigbo, also, Nduka furthers an anti-oppression stance. The late poet’s “Elegy for Alto” becomes an ancestor to “On The Niger” with how it points to the government and its suppression:

The Eagles descend on us,

Bayonets and cannons-

The Robbers descend on us to strip us of our laughter, of our thunder.

The last poem in Waterman‘s first section, “Happy Endings,” is like a screenwriter’s dilemma at coming up with a plausible ending for the show. We meet characters fighting for their lives and the voice trying to make it all make sense:

A loner will not stop crying for her beloved who walked down the railroad and never returned.

Why search the rail tracks for blood stains and familiar clothing?

There’s never sufficient evidence for minority deaths.

Are these lines for Nigeria? Or the USA? Do we have the killers of Kolade Johnson, George Floyd, Jimoh Isiaq, and Vera Omozuwa in custody? We heard the stories of witnesses and family, we saw the clips; we saw them killed, didn’t we?

We can say that Nduka enjoys the throb of everyday life. No other poem in Waterman demonstrates this better than “Arabesque”—the introduction to the poem’s second section. The voice repeats the same line twice—“They say he is mad, yet he keeps watch over his art”—to end the poem’s first and second stanzas, placing, at the center of that interest, an artist. By doing so, the artist relinquishes the power of narration to the other folk, who see a “tormented soul” who’s “clothed in ragged ponchos.” It brings to mind the clichéd image of the artist: tattered and revolutionary. A preacher appears and asks our mad man to believe and be saved. The artist, Nduka beautifully exposes, raises both hands and swears an oath to save his art alone.

In the two final pieces of this middle section, Nduka investigates the human spirit in personal and communal scenarios, which blend into each other. In “The Vendor,” where “street philosophers have mastered the art of making music with speeches sharp like swords,” we’re told that “in [the vendor’s] eyes, hills crash down, a country burns, and rivers overflow with blood boiling out his nation’s anthem in spurious melodies. . . .” The preceding poem, “Memo to My Old Self,” belts those melodies:

I know that body: weak bones and tough flesh bearing the weight of trauma. Hearing voices and leaping to a safety pierced with thorns.

Earth knew the rhythm of feet shaken with fear. How many times did I try convincing the pain to believe my lies and failed?

The phrases “weak bones and tough flesh” and “rhythm of feet shaken with fear” bring back emotions recently witnessed during the End SARS protests, the attacks on young protesters nationwide, the widespread hooliganism which eventually forced everyone off the streets; the incessant gunshots, the Lekki Massacre (of 20.10.20), the subsequent curfew across Nigerian states that had us inside our homes, still not safe.

Waterman pulsates with an urgent message. Nduka’s attention to history and detail courts a journalist’s applause. In precise language, he meets his themes. Our poet is at once worldly and metaphysical, methodical. He allows us a natural feel of the extraordinary.

Waterman by Echezonachukwu Nduka is published by Griots Lounge.

More Reviews from Open Country Mag:

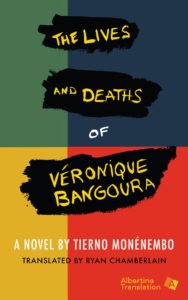

—20.35 Africa Vol. III Review—The Pain Won’t Go Away

—Nsukka Is Burning Review—How a Small University Town Influenced Nigerian Literature

—The Geez by Nii Ayikwei Parkes Review—Threading Family, Love, & Race

—Sacrament of Bodies by Romeo Oriogun Review—An Originative Work by an Epochal Poet

—The Origin of Name by Adedayo Agarau Review—Narrating Grief

—Transcendence by Wana Udobang Review—Woman in the Light

2 Responses

Nice review. I love the easy flow of your thought patterns on this one. Love to read more.