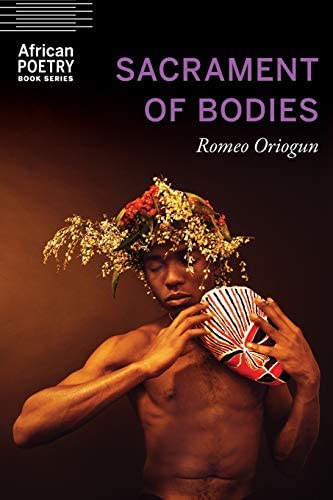

The first poem in Sacrament of Bodies, the debut collection of poetry by the Nigerian poet Romeo Oriogun, was written in February 2016. It was provoked by the lynching of a gay man, Olumide Akinnifesi, in Ondo town, southwestern Nigeria, hours away from where Oriogun worked as a road traffic officer. “I had never been shaken the way I was on that day,” he said in an interview last year. “My bisexual body was fully awakened to the terror waiting outside my door, for it was the day that I realized that even when in hiding, there is no safe space for queer bodies of the lower class.”

This became his main subject. His Brunel Prize-winning breakout in 2017, and the subsequent homophobic harassment he endured, helped create a bigger conversation about queerness in African literature. The prize judges hailed for his poems as “deeply passionate, shocking, imaginative, complex and ultimately beautiful explorations of masculinity.” His chapbooks, 2016’s Burnt Men and 2019’s The Origin of Butterflies (selected by Kwame Dawes for the APBF New-Generation African Poets Chapbook Series), investigate the violence against queer bodies, calling the slain by name and pointing a finger at the world for permitting such atrocity.

In Sacrament of Bodies, Oriogun retains that edginess but goes several steps further by initiating queer people into mythos. They become gods and goddesses, essentially flawed but endlessly beautiful, those whose names are “filled with the myth of creation.”

This is an act of disruption. Oriogun’s authorial voice rests somewhere between prophetic and tourist, filled with experience and wonder. But make no mistake: sometimes, his serene language is a paradox given the vim of their revolutionary stanzas against Abrahamic religions, whose teachings condemn homosexual relationships. The early lines of the collection recall initiations through which “men [are bent] into obedience,” and made “into men empty of the hunger to love in [their] language.”

By describing the peace he receives from African traditional religions, Oriogun charts an alternative path to immortality, though he isn’t forcing that idea himself. This spirituality fills his life and his poetry switches narrative gears almost without notice. At once he’s a worshipper of Olokun, is leading a procession (which naturally includes the reader), and is commenting on succumbing to the wonder of the sea.

Stitching the political and the personal, Sacrament of Bodies traces the genealogy of Black suppression, from the cultural triumph of colonialism over indigenous African traditions to today’s misconceptions about queerness being unoriginal to Black people. Oriogun, charged with this history, criticizes religious imperialism in language that sings and singes:

Who sends a God out of his kingdom

without knowing the weight of sorrow hidden in every mother at night?

Here, we can’t escape every pain that comes with our lineage.

Here, the statues remind us of a long trek we can’t run away from.

We see the priests coming out of water,

the baptism that led to a man taking up a name that will never resemble him.

Death is only the body fulfilling its duty,

not a gateway to a promise made by a man

filled with the Holy Spirit.

– “The Queer Boy Remembers Colonization”

Water as a metaphor for journey persists in his criticism of colonialism, as the early missionaries came in through the shores. Oriogun invoking Olokun through the sea becomes a taking back, a redemption in embracing one’s history.

In that opening piece, “Before Your Mama Knew Us as Light,” he speaks of the intent of today’s religious climate “to imprison joy inside our bones,” and, a few lines later, proudly proclaims: “We are dead in every world except this one wrapped in blue.”

The dark intrigues Oriogun. He uses it as a peculiar poetic device. Whereas natural elements like fire and water represent violence and salvation for queer bodies, and the earth is a marker of geographical nuances (“I own no land that does not own me”), the dark is where queer people are most free to be themselves, hidden in the shadows of the terrifying light that might expose them to a homophobic society.

Oriogun’s men mostly meet in a night club or bar, torn between the hunger of flesh and the danger lurking nearby if they were found in a sinful congregation. The events aren’t always perfect or loved-up. Unsure of their actions, some characters become almost, and sometimes, violent themselves, a fine stroke of storytelling that charges at human psychology and the journey it takes from oppressed to oppressor. It’s a subtle showcase of flaws, of which queer people—even as gods here—aren’t immune to.

In “Satan Be Gone,” named from an Asa song, Oriogun paints pain and pleasure: “He said Satan be gone\as his fist hit me again and again\before his body crawled into a wounded animal at sleep\as I staggered into water and prayed that water and tears would wash the blood flowing down my mouth.”

In “Cathedral of a Broken Body,” he tells of a soldier who submits to the fight in his own heart: “All I knew was him calling my name as if his desire was an ugly beast, as if my face was the enemy.” By the poem’s end, the voice becomes “a baby seeing light for the first time,” and this salvation becomes, we can tell, the turning point of his life.

But ponder briefly Oriogun’s use of military personnel, and why the soldier meets his saving in a brothel. In Nigerian life, the military is the bastion of totalitarianism; their green uniforms inspire fear among common folk like nothing else. For the lightest “offence,” it wouldn’t be unusual to see a soldier beating a feminine man, as they’ve been trained to exaggerate their own masculinity. With the hint of this man’s profession, Oriogun tacks a back story to his person, inherently making him a more rounded character.

He plays a similar hand elsewhere. “Sometimes a Pastor walks through the wooden houses at night to find solace in a boy,” he exposes in “Heaven Is a Back Alley without God,” and “[the Pastor covers the] boy with his hands before calling him sin on Sunday.”

In employing these figures to tell of bias in the institutions of the Church and the Army, Oriogun shows regular queer people, living in the world before they meet the catalysts for their freedom or, more frequently, the sting of homophobia.

Thankfully, Oriogun doesn’t view his characters solely through the lens of adulthood. The poet returns to the family, the social group where one’s gender nonconformity is first challenged. In “Kumbaya,” a father physically assaults the lover of his gay son: “your father smashes our bones against the wall. . . your father digs me out of your stomach. He says no son of mine will be a faggot.”

The word “father” appears 28 times in Sacrament of Bodies, and each time, he is a searing punch against memory, surging through the personae as they move through life. “Praise to our fathers for giving us this gift of knowing the smell of hunters,” the voice concedes.

The mothers in Sacrament of Bodies are more humane, with stories of their own, crumbling under the weight of their prejudices. There’s a tenderness with which Oriogun summons “mother” even as he shows how they’ve tended to be manipulative, all to rid their gay children of “the magic to make boys drop like dead leaves behind you.”

A personal favorite in the collection, “Meeting My Mother Through Death,” has a man looking in a house for a picture of his mother. Oriogun leads a rich tour of what is clearly a family house, noting like a journalist the physical objects—a tree, divorce papers, postage stamps—that made and marred the lives of its past inhabitants. The purpose of the visit is exposed:

I will call a name that was not given to me

and whisper, Mother, I love a man the same way I’ve loved a girl.

I am afraid I might see her flinch

and won’t know if it’s from the light

or from words that cut deeper

into every wound her body has ever known.

Oriogun’s poetry is deeply political despite, or because of, the depth of his characters. Whether he’s calling out oppressive systems or painting a boy-meets-boy scenario, or laying his feet on Olokun’s shores, beauty and purpose are evoked in equal measure.

As a gay African now living in the US, Oriogun knows the beauty of being one’s self openly, in the light. Though the fire chases him no more, his soul wearies with thoughts of his folk elsewhere. His first Pride march inspires “The Guilt of Exile,” a sombre piece where he admits that “every night I reach for home and fail.” He asks: “What is freedom if a million people still walk with the fear of being seen?”

In “The Birthday,” he references Nigeria’s Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act (SSMPA) of 2014, which has a 14-year jail time as punishment for homosexual behaviour. Till today, queer people and activists continue to ask for a repeal of the law, especially as Nigeria’s homophobia was again highlighted by events surrounding protests against police brutality last year.

It is inevitable that Sacrament of Bodies will become an influential work in contemporary poetry from Africa, especially with its centering of queer people. In Oriogun’s journey, it feels like a book he needed to write. Where a weaker hand might falter under the sensitivity of such a subject, his is assured—skills he has been traversing beautifully into prose nonfiction.

At times, the book offers context, other times, it plunges the reader into varying emotions already familiar to queer existence. In “Departure,” the voice confesses: “I worship the day because it survived the night.” Sometimes, Oriogun is neither conjuring nor analyzing but simply living.

Romeo Oriogun’s Sacrament of Bodies is published by the University of Nebraska Press. Buy HERE.

More Reviews from Open Country Mag:

—Nsukka Is Burning Review—How a Small University Town Influenced Nigerian Literature

—The Geez by Nii Ayikwei Parkes Review—Threading Family, Love, & Race

—Transcendence by Wana Udobang Review—Woman in the Light

—The Origin of Name by Adedayo Agarau Review—Narrating Grief

—20.35 Africa Vol. III Review—The Pain Won’t Go Away

—Waterman by Echezonachukwu Nduka Review—A Sobering Stare at the World

4 Responses